– די װילנער פּלײטים האָבן שוין געפּאַקט און געמאָזלט – זאָגט צו מיר אַ פּליט – פֿון דעסטװעגן קענען זײ זיך נאָך אַלץ ניט שטעלן אויף די פֿיס, אַ קלײניקײט, מיטצומאַכן די קינדער־קרענק פֿון אַ פּליט!…

– ערשט װען מיר װעלן זיך שוין אַ שטעל טאָן צוריק אויף די פֿיס – זאָגט ער װײַטער – װעלן קומען די אמת’ע, די “נאַסטאָיאַשטשע” (ער מאַכט נאָך געװיסע װילנער ייִדן) פּלײטים־צרות.

זײער אַ סך אמת איז אין דעם פֿאַרהאַן:

יעדער פּליט האָט זיך שוין דאָ, װי עס איז, אײַנגעאָרדנט, געפֿונען אַ דאַך איבערן קאָפּ, באַקומען אַ שטיקל מלבּוש, אַ מיטאָג אין אַ קיך, בײַגעקומען די רעגיסטראַציע נומער אײנס, שוין מיטגעמאַכט די געגיסטראַציע נומער צװײ און… עס איז נאָך אַלץ ניט פֿאַרבײַ די קינער־קרענק פֿון פּליט – אויף די פֿיס שטײט ער נאָך אַלץ ניט…

דער װינטער איז געװען אַ אויסערגעװײנטלעך שװערער – װי אויף צו להכעיס די האַלב־נאַקעטע פּלײטים. ניט געקוקט אויף די פֿרעסט, זײַנען דאָך די גאַסן געװען פֿול מיט פּלײטים. עפּעס האָט זײ געטריבן, עפּעס האָבן זײ זיך געאײַלט, עפּעס האָט זײ געיאָגט:

װאָס אײגנטלעך?

גאָר פּשוט:

– װי קען מען דען אײַנזיצן?

דער טעלעגראַף־אָפּטײל אויף דער פּאָסט איז שטענדיק פֿול, איבערפֿולט, אײנער איז מקנא דעם צװײטן, צוליב װאָס? ער װײס אַלײן ניט, דערװײַל איז ער אים מקנא:

– אַהאַ, ער טעלעגראַפֿירט קײן אַמעריקע!

– אָט זעסט, יענער האָט בעקומען אַ טעלעגראַמע פֿון פּאַלעסטינע.

יעדער אײנער װאָלט דאָ געװאָלט טאָן דאָס, װאָס עס טוט דער צװײטער. יעדן אײנעם דאַכט זיך, אַז ער איז אָפּגענאַרט, אַז יענער װײס בעסער…

מען לעבט דאָ דערפֿון, װאָס יעדער בויט זיך אויס אַ האָפֿענונג:

– אַ פֿעטער אין אַמעריקע…

– אַ ברודער אין אַרגענטינע…

– סערטיפֿיקאַט…

– אַן אַפֿידײװיט…

און יענער לויפֿט אַרום איבער דער שטאָט. יעדער האָט אַ סוד און יעדער טראָגט זיך מיט אים, אונטערשטעלנדיק דערװײַל אַן אויער צו דעם, צו יענעם, צו אַלע, בײַ װעמען עס באַװײַזט זיך אויפֿן פּנים אַ שמײכל…

– אַהאַ ער שמײכלט!

אולי ירחם! װי קען מען לעבן אָן האָפֿענונג?

און מען לעבט מיט דעם דאָזיקן מנחם־מענדעלשן װוּנטש, אַז פֿון ערגעץ־װוּ װעט שוין קומען דאָס גרויסע געװינס, דער סערטיפֿיקאַט, דער אַפֿידײװיט.

אַ רחמנות, נעבעך…

אולי ירחם…

“The refugees in Vilnius have already had smallpox and measles,” one refugee told me, “and yet they still cannot stand on their own feet. To go through the teething troubles of a refugee is peanuts!”

“Only when we can get back on our own two feet again,” he continued, “will the real, the ‘nastoyashtshe’ [from Russian: real, true, bodily] (he imitates certain Vilner Jews in this) refugee worries begin.”

There is much truth to this:

Every refugee has already made himself a home, found a roof over his head, received some clothes, had lunch in an auxiliary kitchen, participated in the second round of registration… The refugee’s teething troubles are far from over and he is far from standing on his own feet.

The winter was an exceptionally hard one – as if it did it to the half-naked refugees on purpose. Despite the cold, the streets were full of refugees. Something drove them, something made them hurry, something made them hunt:

What was it?

It’s very simple:

– How can you sit down here?

The telegraph department of the post office was always full, overcrowded, one envied the next. Why? One doesn’t really know why, but for the time being one envies the other:

– He telegraphed to America.

– There you see, this one got a telegram from Palestine.

Each of them wanted to do what the other did. Each thought that he himself had been made a fool and the other knew better.

Here you live on the fact that everyone builds up his own glimmer of hope:

– An uncle in America…

– A brother in Argentina…

– A certificate…

– An affidavit…

And they all run around town. Each one hides a secret and each one carries it with him, while you prick up your ears at this or that one, at all those who have a smile on their face.

– Aha, he smiles!

– Ulay yerakhem [perhaps God will have mercy; one must not despair]! How can one live without hope?

And one lives with this wish of Menachem-Mendl [1. Menachem-Mendl is a famous literary figure of the Yiddish writer Sholem Rabinovitsh, better known under his pen name Sholem-Aleichem] that from somewhere the jackpot, the certificate, the affidavit will come.

Ah mercy, the poor…

Ulay yerakhem.

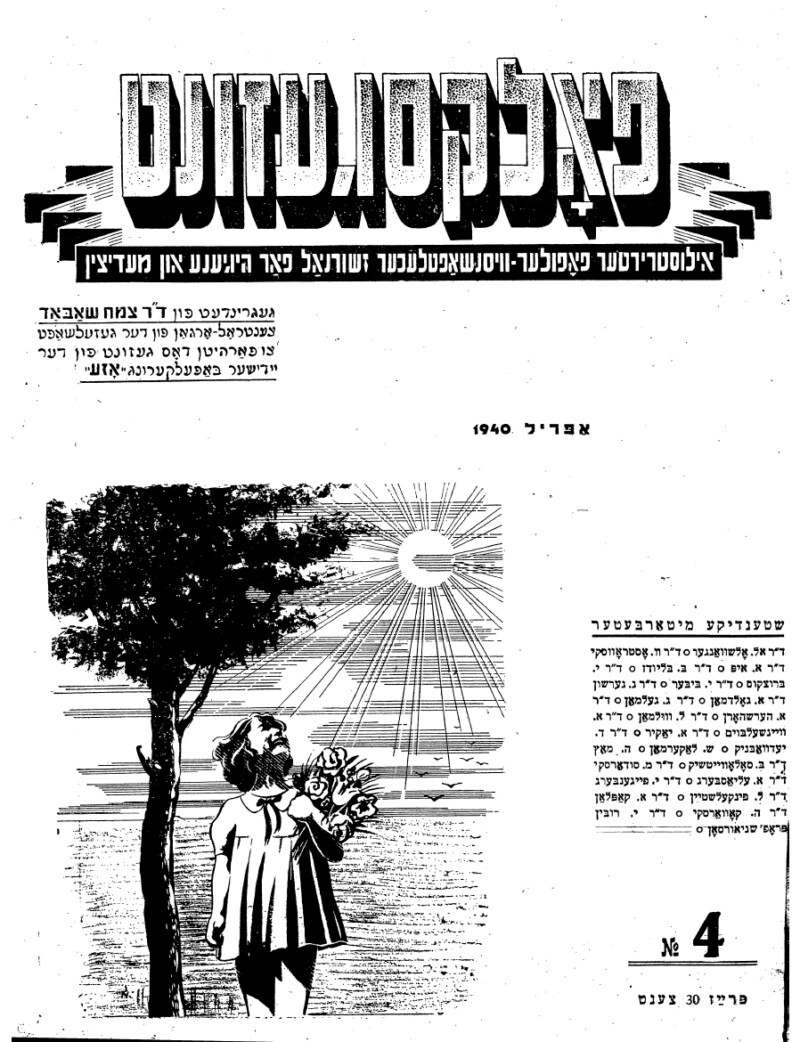

A few days after the German invasion of Poland, Herman Kruk (1897-1944), a Polish Jew and activist of the Bund, decides to flee Warsaw in view of the imminent danger posed by the approaching Wehrmacht. Kruk fled to Vilnius, where he worked as a reporter for the Yiddish magazine Folks-gezunt and published several articles in the spring of 1940, in which he reported and philosophized about the refugee situation, refugee worries, support networks and identity issues.

He lived in Vilnius for almost four years and experienced the fate of the Jewish community under Soviet, Lithuanian, again Soviet and finally German occupation. From 1941 to 1943 he lived in the Vilnius Ghetto. Kruk documented his time in Vilnius as a chronicler and reported on the support networks for Polish Jewish refugees from the German occupation of the city, on his futile attempts to flee the city, on his desperation over the invasion of the Wehrmacht and his grief over the fate of his hometown Warsaw, but also on his motives for recording what he experienced in writing for future generations. In 1943 he was deported to the concentration camp Klooga near Tallinn, where he was murdered in September 1944 shortly before the arrival of the Red Army. Parts of his manuscript are still missing today.

Excerpt:

Kruk, Hermann, April 1940: Pleytim (2ter reportazsh), pp. 11–13 in: Folksgezunt: Ilustrirter populer-visnshaftlekher zshurnal far higyene un meditsin 4, p. 11.

For the whole issue see Epaveldas – Lithuanian Digital Cultural Heritage.