The Arrival of Hannah Arendt

This film describes the arrival of Hannah Arendt - a Jewish, German-American political theorist and publicist - in New York and her reflections on flight and helping people start over.

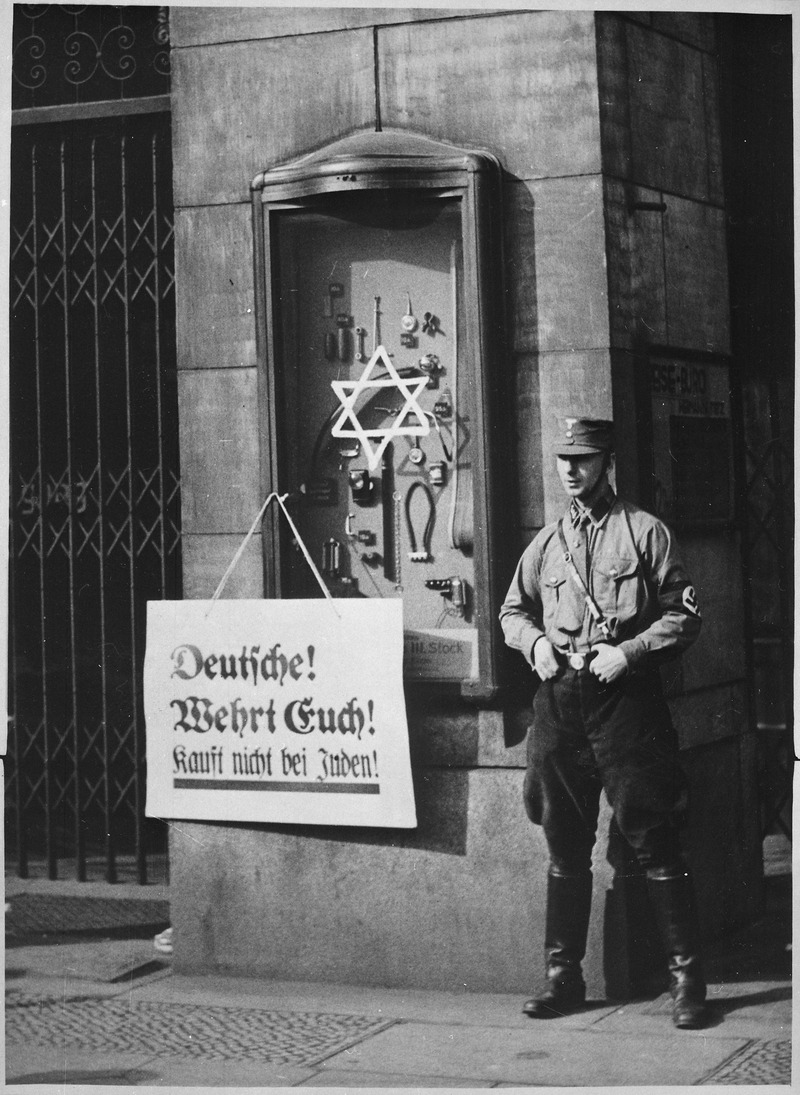

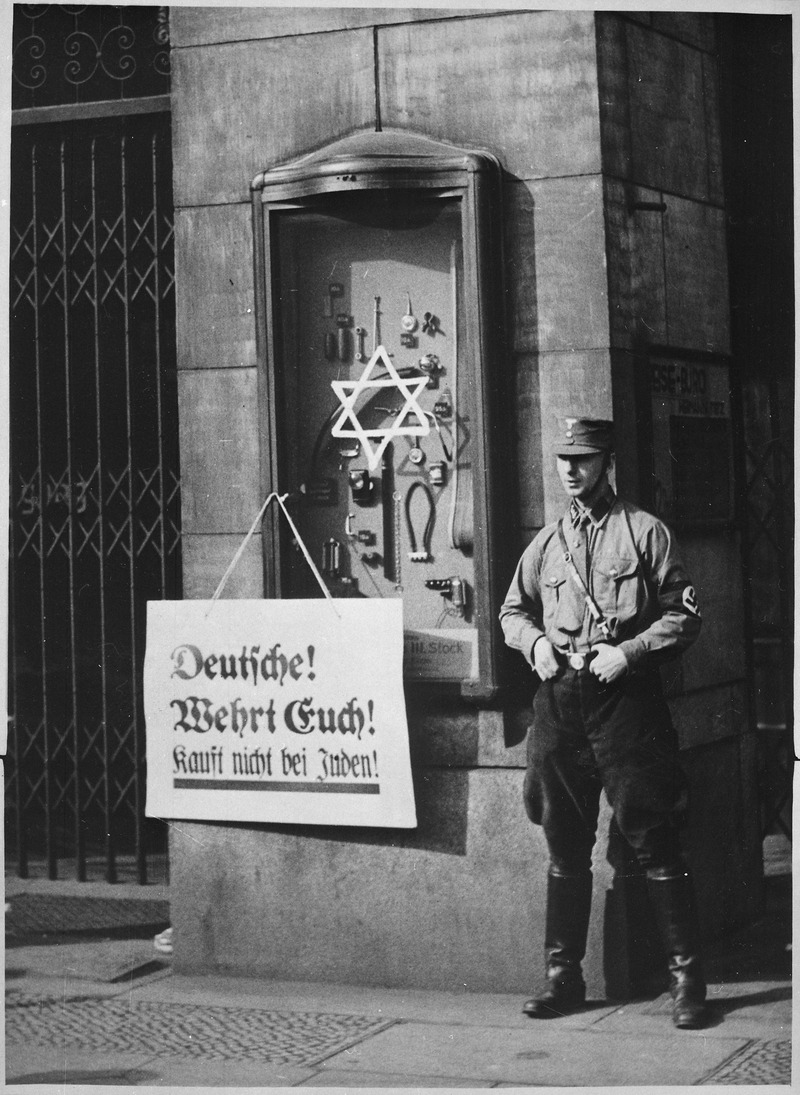

Daß so etwas im 20. Jahrhundert noch möglich ist. Vor allen jüdischen Geschäften, Anwaltskanzleien, ärztlichen Sprechstunden, Wohnungen stehen junge Bürschchen in Uniform mit Schildern „Kauft nicht bei Juden”, „Geht nicht zum jüdischen Arzt”, „Wer beim Juden kauft, der ist ein Volksverräter”, „Der Jude ist die Inkarnation der Lüge und des Betruges”. Die Arztschilder an den Häusern sind besudelt und zum Teil beschädigt, und das Volk hat gaffend und schweigend zugesehen. Mein Schild haben sie wohl vergessen zu überkleben. Ich glaube, ich wäre tätlich geworden. Erst nachmittags kam so ein Bürschlein zu mir in die Wohnung und fragte: „Ist das ein jüdischer Betrieb”? – „Hier ist überhaupt kein Betrieb, sondern eine ärztliche Sprechstunde”, sagte ich, „sind Sie krank”? Nach diesen ironischen Worten verschwand der Jüngling ohne vor meiner Türe Posten zu stehen. Freilich, manche Patienten, die ich bestellt hatte, sind nicht gekommen. Eine Dame hat angerufen, daß sie doch heute nicht kommen könne, und ich sagte, daß es am besten wäre, sie käme überhaupt nicht mehr. Ich selber habe heute mit Absicht in Geschäften gekauft, vor denen ein Posten stand. Einer wollte mich abhalten, in ein kleines Seifengeschäft zu gehen. Ich schob ihn aber auf die Seite mit den Worten: „Für mein Geld kaufe ich, wo ich will”. Warum machen es nicht alle so? Dann wäre der Boykott schnell erledigt gewesen. Aber die Menschen sind ein feiges Gesindel, ich weiß es längst.

Abends waren wir bei unseren Freunden am Hohenzollerndamm, 3 Ärztepaare. Alle ziemlich gedrückt. „In ein paar Tagen ist alles vorbei”, versuchte Freund Emil, der Optimist, uns zu überzeugen, und sie verstehen mein Aufflammen nicht, als ich sage, „sie sollen uns lieber gleich totschlagen, es wäre humaner als ihr Seelenmord, den sie vorhaben…” Aber mein Gefühl hat noch immer Recht behalten.

[…] Aus allen Berufen, aus allen Stellen schalten sie die Juden aus „Zum Schutze des deutschen Volks”. Was haben wir diesem Volk denn bis heute getan? Mein altes Krankenhaus hat seine tüchtigsten und besten Ärzte verloren, die und die Patienten sind verzweifelt, es geht alles drunter und drüber.

With flame writing is this day buried in my heart. That such a thing is still possible in the 20th century. In front of all Jewish stores, lawyers’ offices, doctors’ offices, apartments there are young boys in uniform with signs “Don’t buy from Jews”, “Don’t go to a Jewish doctor”, “Whoever buys from a Jew is a traitor to the people”, “The Jew is the incarnation of lies and deceit”. The doctors’ signs on the houses are sullied and partly damaged, and the people have gaped and watched in silence. They forgot to tape over my sign. I think I would have become violent. In the afternoon a little boy came to my apartment and asked: “Is this a Jewish business? – “This is not a business at all, but a medical consultation,” I said, “Are you sick?” After these ironic words, he disappeared. Of course, some of the patients didn’t come. A lady called to say that she couldn’t come today after all, and I said that it would be best if she didn’t come at all. I myself bought today on purpose in stores in front of which there was a post. One of them tried to stop me from going into a small soap store. But I pushed him aside with the words: “For my money I buy where I want”. Why doesn’t everyone do it that way? Then the boycott would have been over quickly. But people are a cowardly rabble, I have known it for a long time.

In the evening we were with our friends at Hohenzollerndamm, 3 pairs of doctors. All quite depressed.”It will all be over in a few days,” friend Emil, the optimist, tried to convince us, and they don’t understand my flare-up when I say, “They’d better beat us to death right away, it would be more humane than their soul murder they’re planning…” But my feeling was still right.

[…] From all professions, from all jobs they eliminate the Jews “For the protection of the German people”. What have we done to these people until today? My old hospital has lost its most capable and best doctors, they and the patients are desperate, everything is going haywire.

Hertha Nathorff, née Einstein (1895-1993) was a German pediatrician, psychotherapist and social worker, she published several works, including a book of poems. She was born in Laupheim (Baden-Württemberg) into a Jewish family. She was related to the physicist Albert Einstein, the musicologist and music critic Alfred Einstein, and the film producer Carl Laemmle. Nathorff attended high school in Ulm and, interrupted by a temporary job as a nurse during World War I, studied medicine in Munich, Heidelberg, Freiburg (Breisgau) and Berlin from 1914. After receiving her doctorate degree in Heidelberg (1920) and years as an assistant in Freiburg, she was a senior physician at the Red Cross Women’s and Children’s Home in Berlin-Lichtenberg from 1923-28, then worked in private practice and simultaneously at the Charlottenburg Hospital as head of the family and marriage counseling center. In the course of National Socialist racial policies, she lost her medical license in the fall of 1938, while her husband, formerly a senior hospital doctor in Berlin-Moabit, was granted a license for exclusively Jewish patients. During this period she worked as his receptionist.

Threatened with death in Nazi Germany, she organized emigration with the help of American relatives from November 1938, sending her 14-year-old son ahead to England on a Kindertransport. In April 1939 the couple managed to leave the country for London, and in early 1940 they continued their journey to New York. In New York she worked as a nurse, maid, bar pianist and kitchen help to support the family. She remained a physician’s assistant in her husband’s practice, which opened in 1942 – she did not have the time to get her degree recognized.

Hertha Nathorff took a very active part in the social life of the German-speaking exile community: she organized courses for emigrants in nursing and infant care and cultural events, was the founder of the Open House for the elderly, chairwoman of the women’s group, and an honorary member of the presidium of the New World Club. In the excerpts from the diary of Hertha Nathorff Berlin-New York Aufzeichnungen 1933 bis 1945, which we show in our archive, the author deals with her initial problems, disappointments and mortifications in the New World. She reports on the everyday life of emigrants, on the struggle for existence, on poverty and mental destruction. Despite her longing for the places of her childhood and youth, she never visited Germany again. She never really settled in America. The homesickness remained constant.

Excerpt from the diary of Hertha Nathorff, edited and introduced by Wolfgang Benz (1987): Das Tagebuch der Hertha Nathorff. Berlin – New York. Aufzeichnungen 1933 bis 1945. Schriftenreihe der Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte, Band 54. R. Oldenbourg Verlag München, pp. 38-39.

Translation from German to English © Minor Kontor / We Refugees Archive.