I am not a ‘refugee’ in Berlin. I have left my refugee ID card in Istanbul, that city that used to be the girlfriend, the city that taught me how to dance and turned me into a sponge that swallows bars and never gets drunk. I flew to Berlin because after Trump’s ‘Muslim ban’ I was refused to enter the US where I had received a scholarship to finish my degree in Petroleum Engineering. I was given an opportunity to study in Berlin. I am here on a student visa, but still a refugee in Istanbul.

It’s inherited in my personality to be always looking for a home, to dance when I hear Arabic music, even if I am at the greatest of my sorrows. I put on the new Airpods I got as a gift for my birthday, on my third-celebrated birthday ever. I am 29, and I never had a birthday party in Syria.

I begin thinking about the city I belong to. The memories in my head clash and clatter. I belong to both Istanbul and DeirEzzor, but when I think about ‘home,’ I smell water, rivers, and the ocean.

I open the ‘Painter app’ on my phone. I draw a river in blue and a girlfriend in red. That’s my home.

The music starts slow as I take the elevator to the last floor of my office building. I start chasing the Spree River lines. It doesn’t look like my Euphrates – the famed birthplace of the civilization I belong to. It doesn’t look like the Bosphorus. Metal buildings and techno music besiege the Spree.

I start thinking about Berlin from above. Potsdamer Platz was completely rebuilt after the fall of the wall and I am in the highest building in this area, a capitalistic center where lots of NGOs and corporations have their offices. I bet there are a hundred nationalities in this building in the morning, but it’s Saturday, 8.30 pm, and people must be preparing to go dancing somewhere. The space changes and shifts through time. It’s as if I am in a completely different zone.

I am alone in the building: just me and the lights. I am scared.

I used to think – the first time I took an airplane from Istanbul to New York back in 2015 – that God must be happy looking at Istanbul from high up. I used to tell myself, ‘It is a city that makes gods laugh.’ And now, while I am on the 20th floor of the WeWork Atrium tower, I ask myself if God feels happy looking at Berlin from above. What does God think of looking at a city full of lights, metal, and questions? What is ‘god’? Is ‘God’ a she or a he? I used to be the only religious kid in my family, I never doubted ‘God’. Berlin is a city of extraordinary questions and no answers. It never answers.

In the introduction to All That Is Solid Melts Into The Air Marshall Berman writes: ‘To be modern is to find ourselves in an environment that promises us adventure, power, joy, growth, the transformation of ourselves and the world — and, at the same time, that threatens to destroy everything we have, everything we know, everything we are’. This statement doesn’t only pertain to the urban development and destruction humans are causing, it also refers to our own being, and our personalities. I am not the same kid that sleeps on the streets anymore.

In my city, I used to run out to the streets when electricity was cut off. And, believe me, this happened a lot. I liked the darkness because it opened our windows/eyes towards the sky. There was no haze, no clouds, and it never snowed in my town. I used to lie on the street and look up at the sky, naming the stars after the people who mean a lot to me.

Now, I look at Berlin from above, and ask myself, how did the sky fall onto the streets? How did they get all these stars on such empty streets? What names can I give these street lights? What is love? What am I?

I start walking from Potsdamer Platz towards the subway station. The night is a friend of refugees and tired workers, it wraps their faces in darkness just as those who cry hide under the rain. The river, next to the station, has a bridge arched over it. I start remembering the bridge of my first kiss, in my hometown. That bridge is completely destroyed now. I am on a bridge of no memories for me, but it has the spirit of my childhood bridge. It cuts the river in half. Space collapses, and the bridge cuts me in half. The river here is also different than the one in my city. There, it’s like a vein, or a generous grandmother who keeps feeding you, even if you swore a thousand times that you are already very full.

The Euphrates is me, and it keeps floating, it keeps moving, it never stops.

In Berlin, the river cuts the stars, the lights, and the newly constructed buildings. Here there are few humans around at night. I look around, no one is here. So, I shout.

I take the U-Bahn and go towards Hermannplatz, just off Sonnenallee known as the ‘Arab Street.’ A place where ‘refugees’ find a home, amongst the Arabic names of restaurants, supermarkets, and shisha bars. It’s also where modernity expresses itself on multiple levels. All this globality within one neighborhood. A McDonald’s close to Aldimashqi restaurant. Lots of rental e-scooters scattered near a guy asking for ‘money for weed’ as the cardboard sign he holds proclaims.

In his essay ‘Walking While Black,’ Garnette Cadogan talks about his experience of being a young black Jamaican man walking in New Orleans: ‘I wasn’t prepared for any of this. I had come from a majority-black country in which no one was wary of me because of my skin color. Now I wasn’t sure who was afraid of me.’ I have felt like this a thousand times in Berlin.

The ‘Arab Street’ is a place where I experience the reality of being ‘normal’ on a street where most of the people look like me. I hear Arabic every two meters as I walk. I smell ‘Arabic’ food on every corner though restaurant workers aren’t as generous with sauces and flavors as they used to be back in Syria.

The Arab Street never closes its doors to Berliners. The frying oil smell is always there, a friend or a foe to the people who pass by. I shout again, in front of the restaurant. A kid standing by with his mom laughs at me.

All history moves towards one goal, the manifestation of God.

Stephen jerked his thumb toward the window, saying:

– That is God.

Hooray! Ay! Whrrwhee!

– What? Mr. Deasy asked.

– A shout in the street, Stephen answered.

— James Joyce, Ulysses

In Syria, I used to shout for freedom and democracy since the first day of the revolution. I took to the streets, was chasing death and life, teasing both, poking them like a friend. I did not want to die, but I did not care if it happened. Every time I went out, I dropped a kiss on my mother’s cheek and asked her to forgive me. Shouting was an expression of resistance. It was my alphabet of freedom. Shouting was a celebration of all the values I believed in.

During my walk in Berlin, I shout only three times. On the bridge, in front of the restaurant, and in a shisha bar, as I call out to the shisha boy to bring me more coal. I smoke shisha every day, until my throat is sour. Until I feel the same pain in my throat that I felt in Syria, back when I was a protester. I never tasted an excellent ‘shout’ after I left Syria. I never knew in which language I should shout outside of my hometown. There is a different meaning to my voice now, and almost no meaning for my shouts.

I lost my voice singing at a concert when a Syrian band called Khebez Dawleh was singing about home and rivers. Now I don’t know what’s home. Now I don’t shout as I please. During this walk, these self-prescribed shouts made a little sense. And yet, they made me jump back into the memory; they made the space shift, merge, confuse me, annoy me, and make me happy — a thousand feelings in one single shout. I smelled the Euphrates while I was standing on the bridge near Potsdamer Platz. One leg was rooted in the cement I was standing on. The other was on a cloud. I was cut in half.

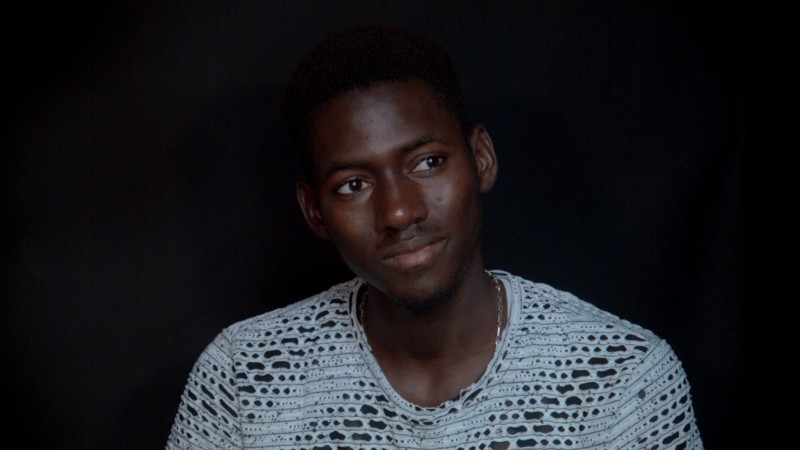

Karam Alhamad is a human rights activist and international development practitioner. He studiedeconomics, politics and social thinking at Bard College Berlin. He fled from Syria to Turkey and then came to Berlin as a student.

In the text “On the frontline: Walking While Cut in half”, he writes about disruptions and changes in his own identity, about what connects and distinguishes his hometown on the Euphrates and his city of refuge on the Spree, about his protest activities during the revolution in Syria, and about how he feels less excluded in Berlin’s Sonnenallee than in other places in the city.