[page 3] Hitler entered Austria on Saturday, March 12, 1938, my father’s birthday and two days after mine. My twelfth birthday party, planned for Saturday, had to be cancelled. I was very upset about this, and I did not understand that our world had come to an end.

At the time I was in my second year of gymnasium, the equivalent of sixth grade in the United States. School reopened the following Wednesday. A few children did not return and others left during the rest of the school year. I finished the term and so did my two best friends, Edith and Gerty, who lived on the same block as we did. Edith and her family left at the beginning of summer for France and eventually arrived in the United States. After Edith’s family left, her nursemaid telephoned Gerty and me and said we were welcome to any of the toys and games we fancied. Gerty’s parents and mine were horrified when we showed up at home with a [page 4] lot of junk because they knew that soon we would all have to leave Vienna. Gerty already knew that Australia was their goal.

A few days after Hitler marched into Austria, I was playing in Edith’s house, when mother telephoned me to come home immediately. She knew that the Gestapo was about to search Edith’s house. I procrastinated and was caught there and not allowed to leave for about an hour. I was not scared, but my parents were. Finally the Gestapo permitted me to leave, but not before searching me. That afternoon, I was wearing a coat inherited from Gerhard, which had breastpocket. Three days before Hitler annexed Austria, the Austrian Chancellor, Kurt Schuschnigg, had announced a plebiscite to prove to Hitler that the Austrians did not want him. Airplanes had dropped thousands of propaganda leaflets in the streets before the vote. The plebiscite never took place, but one of the leaflets was in the breastpocket of my coat, picked up on March 9, on my way to school, and long since forgotten. Luckily, the Gestapo overlooked that pocket. When I returned home, my mother was furious, searched me again, and found the leaflet. […]

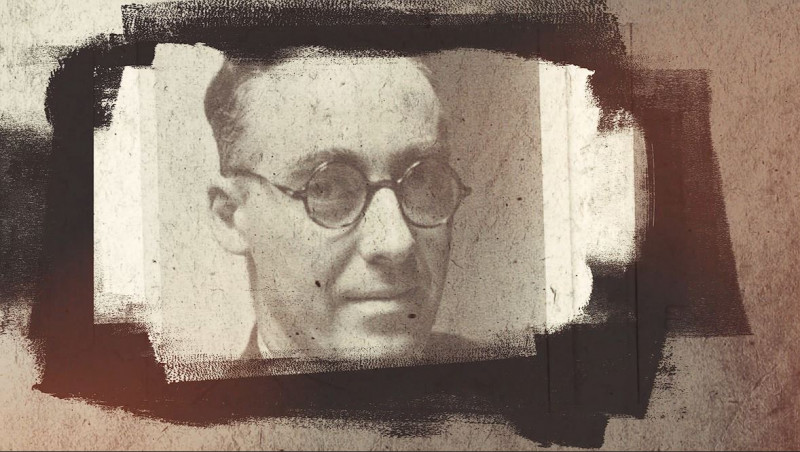

[page 5] We had our apartment dismantled, packed and shipped to Hlinsko, Czechoslovakia, where my family’s upholstery mill was. Hlinsko was also our destination. (The crates were never unpacked while we were there and I do not know who got the furniture and household goods in the end, the Nazis or the Communists.) But Czechoslovakia had closed its borders, and Jews had a hard time obtaining an entry visa. My father was anxious to get out of Austria and found a “Macher” – an arranger – who, by bribing various bureaucrats, would arrange my parents’ and my emigration. Gerhard [Susanne’s brother] had already left Vienna for Hlinsko in 1936 to work in the mill.

We left Vienna on August 17, 1938, ostensibly as tourists. Cousin Fred Frankl came to stay with Grandmother Paula. I still see them at the window waving to us as we left by car. Earlier that day my grandparents came to say good-bye. I never saw them again. My friend Gerty, too, came to say good-bye and to play one more time. She inherited all my games and toys plus my part of the loot from Edith.

Ludicrously, we left Vienna in a chauffeur-driven car flying the Nazi flag, accompanied by the very Jewish-looking Macher. The first night we stayed in Graz with Grandmother Luise’s family. The following day we crossed into Yugoslavia to wait for the Czech visa. [page 6] My mother was very pleased when the Yugoslav border guard asked the driver to remove the Nazi flag.

The car dropped us in Ljubljana, the first larger town in Yugoslavia, where we stayed a few days. […] We moved to Zagreb and soon after to a spa outside the city where we lived in an old and primitive farmhouse. […]

In September, while we were at the spa near Zagreb, Hitler passed an edict that all Austrian passports were to be exchanged for German passports. Jews were to have the names Sarah and Israel added to their names and a big red J (for Jude) was to be stamped on the first page. We were told that the German consul in Sarajevo was not a Nazi or anti-Semite and would not comply with the latter part of the edict. He would issue regular German passports.

We left with Carl via Belgrade, capital of Yugoslavia, for Sarajevo, where I had my first exposure to Muslim culture. That part of Yugoslavia had been under Turkish domination for a few hundred years. I loved everything: bazars with their smells and tradespeople and artisans; the many mosques with the beautiful [page 7] carpets; and the – for me – strange customs. But I was horrified when I saw a whole lamb being roasted on a turning spit, its glassy eyes looking at me. First we lived in a hotel, but could not afford it for long. Neither could we afford to maintain Carl. Father went to the Ashkezani Jewish Community to ask for help. Sarajevo had two Jewish communities – one Ashkenazi, the other Sephardi – both wealthy, but with little sympathy for each other. […]

Before he could issue the J-less passport, the German consul wanted proof that all of us had been baptized for at least five years. Because his parents converted before he was born, my father was Catholic since birth. But mother and I had to get a baptismal certificate. Through friends, father found a Serbian-Orthodox [page 8] priest (Serbian-Orthodox is the dominant religion in Serbia and Bosnia) who for monetary consideration was willing to baptize mother an me and to predate the baptismal certificates. The ceremony took place in a small village church in the mountains. Our taxi driver took the sharp curves on the narrow road up the mountain much too fast, and I did not think we would survive the day, especially as I felt guilty for being baptized. Father had implored me to behave during the ceremony. It was rather a strange scene. At one point Mother and I had to walk three times around a rickety table holding a candle in our hands, while the priest mumbled incantations in a strange language. Neither of us dared to look at each other for fear of bursting out laughing. Soon after we handed in the baptismal certificates to the German consul, our German J-less passports were issued. […]

[page 9] On September 30, 1938, Chamberlain and Daldier caved in to Hitler’s pressure. Hitler then marched into the Sudetenland. The many Jews in the Sudetenland fled to the rest of Czechoslovakia.

Our Yugoslav three-month visas expired in the middle of November, and we left with our brand new German passports for Budapest. Little did we know at that time the problems the German passports would create the next time we went to Yugoslavia. […]

[page 10] Our Czech visas were issued and around Christmas 1938 we left Budapest by train for Hlinsko. […] The whole idea of going to Hlinsko was to get money out of our family’s textile mill for our flight to Central Europe. Of course it was too late. […]

[page 11] Towards the end of August, father wanted to leave Czechoslovakia. However, the Nazis demanded an exorbitant tax, and we did not possess the money. The only way out was to cross the border illegally. Father found a “Macher” who would organize our escape to Poland. He knew guides who would walk us across the border. We took a train to Luhacovic, a spa in the eastern spa of Czechoslovakia, near the border with Poland.

Talk of war was rampant, and I was absolutely petrified when I saw from our train freight train after freight train with military equipment passing us. Since not all four of us could cross the border at the same time, it was decided that father and I would to one night, and mother and Gerhard the following night. After [page 12] one night in the spa, where we blended in with other tourists, father and I took a train to a small village closer to the border with Poland, from where we were to leave before dawn the following morning.

I remember those days as the worst of our three-year Odyssey. I was scared of war, scared of crossing the border, and scared of leaving Mother and Gerhard behind. Would I ever see them again? Father asked me to go to bed early so that I would not be tired the following morning. I could not fall asleep. I had never been in such a primitive house in my life. Hooded figures came and went, whispering to each other. Finally I did fall asleep. When I woke up I realized immediately that something had gone wrong, because the dawn has passed and the sun was shining brightly. Father told me that we could not because a German soldier had been shot and martial law declared; it would be too risky to try to cross the border.

So we returned to Luhacovic to the great surprise of Mother and Gerhard. After some debate our parents decided to return to Prague rather than try to cross again into Poland. War broke out shortly after our return to our apartment. The murder of that German soldier probably saved our lives. Had we succeeded, we would surely have been trapped in Poland. Later we learned that the guides robbed the Jews of all their belongings before showing them the way into Poland. Our Australian visas arrived about that time, be we could not use them anymore because we were now in enemy territory. […]

[page 13] Since in the fall of 1939 I had not yet reached my 14th birthday, I was legally obliged to attend school, but by law it had to be a Jewish one. Every morning I took a suburban train to Prague to attend school. […] Every day the student body changed. Some children left for countries all over the world, only to have their places taken by new arrivals.

Father decided to try to cross into Slovakia during the Christmas holidays. Again a “Macher” arranged our crossing. Again we left, as from Vienna, disguised as tourists. This time, however, we were going skiing. […] The arrangement was that my parents would walk or ski with a guide into Slovakia, and I would be driven in a car by the “Macher” and his girlfriend. Our rendezvous was at a restaurant in a village on the Slovak side. Unfortunately, we did not know that the small village contained a bar and a restaurant with the same name. So my parents wound up in one place and in the other, [page 14] and we all sat for hours, waiting for each other. It was as harrowing an experiment as when we had tried to cross into Poland. Finally the “Macher” started to investigate and learned about the bar with the same name and my parents and I were reunited. […] we were on our way to Bratislava, capital of Slovakia. Gerhard was there to greet us. […]

[page 15] After a few days in Bratislava we continued to Budapest, but without Gerhard. We had visas for Hungary and Yugoslavia, but Gerhard did not. […] One day Gerhard appeared. He had crossed the border from Slovakia to Hungary illegally. The owners of the pension let our parents hide him in their room, which I had shared with them. I moved in with one of the other guests. Gerhard and I played Monopoly every day for hours.

One very early morning the police came to the pension to determine whether anyone was living there illegally. One of the guests took me from the lounge to her room so that the police would not interrogate me. I was very apprehensive. I need not have been, since Father again handled the situation with his usual characteristic fast thinking. Since it was early in the morning, Mother was still in bed and my brother Gerhard about to get dressed when the police marched in. When the police asked him [page 16] the identity of the young man, Father, feigning embarrassment, told them that he was impotent and that the young man was his wife’s lover. The police were full of sympathy and left.

Gerhard waited for a certificate (visa) to go to Palestine, which friends in Tel-Aviv had arranged for him. The only ones available were for a Yeshiva (Talmudic Academy). When the certificate arrived, Gerhard had to join a group of Yeshiva-bochers (Yeshiva students). He was worried that he would not know how to behave. Before he left for Trieste, Italy, to board the boat, he bought a hat to look more religious. But, it blew away the first day out to sea. Shortly before our three-month visa for Hungary expired, Father managed to acquire Italian visas for us. We still had the German J-less passports, which made things easier. […]

[page 20] Sometime in May we left for Italy. Father wanted to leave since he was convinced that Italy was going to attack Yugoslavia and he preferred to be in the country that was attacking rather than in the one being attacked. Our destination was Nervi on the Italian Riviera, east of but not far from Genoa. […]

[page 21] After Italy entered the war, Hitler’s influence on Mussolini increased, and life for Jews became harder, especially refugees from Germany and Austria. […] We still had the same passports, so back we went to Zagreb. […]

[page 22] One of the new refugee couples we met had heard that the Argentinian consul in Sofia, the Bulgarian capital, sold Argentinian passports, good for any country but Argentina. Off went my father and new friend Mr. Goldberg to Sofia to check the rumor, which turned out to be true. I don’t [page 23] recall the exact sequence of the deal, but one day soon thereafter we were proud owners of brand new, bright blue passports. I remember that the other couple changed their name from Goldberg to Garvin in the process.

Now our next destination was Istanbul, Turkey.