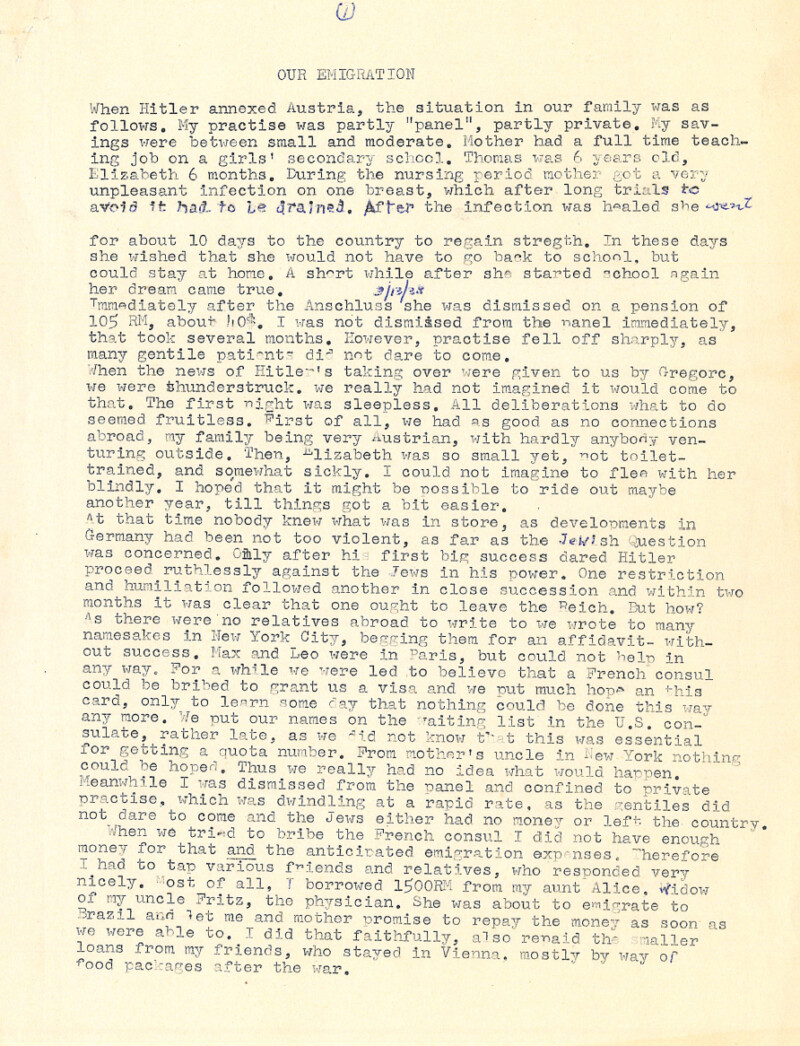

Our Emigration

When Hitler annexed Austria, the situation in our family was as follows. My practise was partly “panel”, partly private. My savings were between small and moderate. Mother had a full-time teaching job on a girls’ secondary school. Thomas was 6 years old, Elizabeth 6 months. During the nursing period mother got a very unpleasant infection on one breast, which after long trials to avoid it had to be drained. After the infection was healed, she went for about 10 days to the country to regain strength. In these days, she wished that she would not have to go back to school, but could stay at home. A short while after she started school again, her dream came true.

Immediately after the Anschluss [3/13/38], she was dismissed on a pension of 105 RM, about 40$. I was not dismissed from the panel immediately, that took several months. However, practise fell off sharply, as many gentile patients did not dare to come.

When the news of Hitler’s taking over were given to us by Gregorc, we were thunderstruck. We really had not imagined it would come to that. The first night was sleepless. All deliberations what to do seemed fruitless. First of all, we had as good as no connections abroad, my family being very Austrian, with hardly anybody venturing outside. Then, Elizabeth was so small yet, not toilet-trained, and somewhat sickly. I could not imagine to flee with her blindly. I hoped that it might be possible to ride out maybe another year, till things got a bit easier.

At that time nobody knew what was in store, as developments in Germany had been not too violent, as far as the Jewish Question was concerned. Only after his first big success dared Hitler proceed ruthlessly against the Jews in his power. One restriction and humiliation followed another in close succession and within two months it was clear that one ought to leave the Reich. But how? As there were no relatives abroad to write to we wrote to many namesakes in New York City, begging them for an affidavit – without success. Max and Leo were in Paris, but could not help in any way. For a while we were led to believe that a French consul could be bribed to grant us a visa and we put much hope on this card, only to learn some day that nothing could be done this way any more. We put our names on the waiting list in the US consulate, rather late, as we did not know that this was essential for getting a quota number. From mother’s uncle in New York nothing could be hoped. Thus we really had no idea what would happen. Meanwhile, I was dismissed from the panel and confined to private practise, which was dwindling at a rapid rate, as gentiles did not dare to come and the Jews either had no money or left the country.

When we tried to bribe the French consul I did not have enough money for that and the anticipated emigration expenses. Therefore, I had to tap various friends and relatives, who responded very nicely. Most of all, I borrowed 1500RM from my aunt Alice, widow of my uncle Fritz, the physician. She was about to emigrate to Brazil and let me and mother promise to repay the money as soon as we were able to. I did that faithfully, also repaid the smaller loans from my friends, who stayed in Vienna, mostly by way of food packages after the war.

[2]

People were arrested and shipped to concentration camps in order to put pressure on them to emigrate. We were told that by Oct. 1st we would have to leave our apartment. One day mother found that the usual place of her walks with the children, the Tuerkenschanzpark, had a sign: “Jews enter at their own risk.”

But where was one to go? All countries, suffering from massive unemployment as they were, had stopped giving visas to people who evidently wanted to emigrate. The real emigration countries overseas were making the most terrific difficulties. The pressure on Jewish people was mounting every week. We were warned that after Oct. 1st new persecutions were planned.

The only country to be considered was Jugoslavia. One could get a three months tourist visa, if a certificate of baptism was presented. Therefore we got a Family Passport which was easier said than done. But we got it after great difficulties. It was necessary to prove that one owed the government no taxes, to get numberless stamps and approvals, which involved long, tense hours.

At the final stage mother persuaded the SS man who puts his signature on the passport to give us two years validity instead of one only, as was usual for the Jewish passports. This way we were less conspicuous.

Then we took the passport to the Jugoslavian consulate with my and the children’s certificates of baptism. Next day we had our visa.

A very short time later that would not have been possible any more, because all people who according to the Nazi laws were Jews got a big J stamped in their passports and that would have prevented the Jugoslavs to give me a visa, baptism or not.

Grandmother, who could not present a certificate of baptism and could not be put on my family passport, was thereby prevented to come with us. We planned to let her follow the moment a way opened. Later on, in Paris, the time seemed right and mother prepared the way for her to come there. But the outbreak of the war made it impossible.

As we were allowed only 20RM to take out of the Reich it was of great importance to find some legal way to take out more money. The Jugoslavs had an agreement with the Reich that citizens of the latter could, when they came as tourists, pay a certain maximum amount of RM and, once in Jugoslavia, got the corresponding value in their currency. But it was necessary that a police doctor attested that the stay in Jugoslavia was important for reasons of health. Mother capitalized on her past breast infection and got the doctor to sign the paper willingly. Thus, the stage was set.

We tried to depart as secretly as possible and told hardly anybody. I don’t think that was necessary, but we thought it better. We left the apartment, furniture, and everything that was not taken along to the care of grandmother, asking her to sell whatever she could. We had a shipping firm pack several crates with books, musik [sic!] and china etc. and asked them to wait for our orders where to ship them.

We took along two big ship trunks, several big suit cases, a box for ladies’ hats and a big shoe bag. For we had bought clothes and other things to wear for the coming lean years. Most of the silverware had to stay back, but I dissembled my microscope, put it on the bottom of a big trunk and brought it safely through the customs inspection.

In connection with the Jugoslav visa something has to be mentioned which I omitted in the original page, which was meant for Lisa in the first line.

Mother, of course, had no certificate of baptism to show. But I trusted 1) on the family passport, 2) on the 3 available certificates of baptism and thought mother would be allowed to ship through.

But mother was not so trusting and wanted to make sure, as far as possible.

Without any prompting or even a mere hint from me (who indeed never even thought of it), she decided to get a certificate of baptism. She went to a certain Anglican minister, took a prescribed course of instruction from him. [Every time she came home after the lessons she was in bad humor and took her anger out on her mother and on me. It went too much against the grain.] Finally, she did the confession of faith and obtained her certificate.

When the passport with the Jugoslav visa had to be picked up and the certificates presented, we decided that she should do it, having more presence of mind and also sheer luck than I. It was a very ticklish thing, because the minister had put the night date and the certificate and that was dangerous. Therefore, mother wanted to use the certificate only in the most dire emergency. Thus, with innocent [smile?] she presented the 3 good certificates to the girl at the Jugoslav embassy. The latter asked: where is your own? Then mother faked a hunt through the handbag and finally declared she must have forgotten it at home. Should she go back and get it? (gambling everything on one card). But the girl said: No, it’s all right, I believe you. And gave her the passport.

At the border, I showed only certificate and was not asked for the others.

Please do not mention this to Lisa, at least for a while. Also not to mother.

[3]

Our plan was to go to Zagreb, where I had several friends, on whom I counted to help us with advice and with the language.

The further idea was to work from Zagreb for a French visa, because we thought behind the Maginot line we would be safe.

We had a gentile lady friend, Mrs. Borri, a native of Trieste, Italy. We knew her from Kauder’s choir and had struck up a friendship with her. She had a brother in Trieste in a shipping line, who had good connections to the various consulates.

One day Mrs. Borri visited us and we told her of the impending departure and how hard it would be to make all the necessary arrangements with the small children around. All of a sudden mother said impulsively: Mrs. Borri, come with us and help us the first few days. And maybe you could go from Zagreb to Trieste and get us a French visa. She was somewhat taken aback, as she had a husband and a child, but she agreed after a very short while. So, we got her a visa, which was infinitely easier, paid her expenses and she stayed with us the first 10 days.

Meanwhile Hitler was stepping up his propaganda against Cechoslovakia, men were called into the army every day, rumors were flying right and left that there would be war, that soon nobody would be able to leave etc. thus, as the day of our departure approached the political situation became as tense as possible and everything became questionable. The last few days were nerve-racking indeed. Just on the day of our departure, Sept. 15, a practise blackout was ordered. After nightfall, the taxi came and we proceeded through the dark streets to the railway depot with Mrs. Borri and grandmother, the latter to see us off. At that time nobody was used to a blackout and it was quite depressing, also on the depot, where all lights were extremely low. The custom inspectors had to go through all the trunks, which took a long time. Finally, they were through, we said good-bye to grandmother, to whom I had given all the money I had left, believing it would tide her over, till we could let her come.

I had heard stories about the thoroughness with which emigrants were searched at the border. Therefore, I was careful not to have anything illegal. The jewelry I had inherited from my mother I put on Mrs. Borri. But when the border came and I faced the big ordeal, there was almost nothing. Nobody bothered us, just the official formalities with passports and stamps. Then we were out of the Reich and in Jugoslavia.

In Vienna, both mother and I had to sign that we and the children would never return to the Reich. We were very willing indeed to promise that. Now we were out. I cannot say that the passing of the border caused any emotion in me, positive or negative.

It became gradually lighter and in the morning we arrived in Zagreb.

It was a completely unfamiliar town to me, with a different language. We put the big trunks into the baggage room and started to look around for a place to stay preliminarily. There were porters of various hotels on the station and after investigation, we picked one and took a taxi to get there. The chauffeur talked German and I asked him whether by any chance he knew a Dr. Clara Zupic. he told me that she was his doctor and lived quite close to where we were. He drove us there and I went to her door and rang. I knew that lady from Vienna, where she had been a classmate and friend of my sister in medical school. She opened

[4]

and exclaimed: George, how you look! I had the ashen complexion of all the refugees, who were worrying themselves sick about what to do etc. When I told her we were going to that hotel, she said: that is much too expensive, stay here. She did not listen to my objections (5 people, of whom two small children), but said we should absolutely come. Later on, we could see what to do next. Thus, we uploaded and she put us into their bedroom. After a few hurried telephone calls to our mutual friends it was arranged that I could sleep in the house of the widow of my former chief, which I had known for many years.The others had to stay in that bedroom, which was a very unpractical arrangement.

Then we had to organize feeding the children and ourselves, taking care of the diapers etc. It was a gipsy-like existence. We caused our hosts great inconvenience and we could not leave the bedroom during office hours etc.

Meanwhile our friends had become alerted. One helped me to get my money from a bank and for the moment I was financially independent. Mrs. Borri helped us very nicely to mind the children. We ate in shifts in a restaurant; life was quite complicated. After the first few days we asked Mrs. Borri to go to Trieste and try her best for us. She left and we were waiting anxiously for the answer. Meanwhile the Sudeten crisis went into high gear and everybody expected war to break out at any moment. But for the time being, we had quite enough with our private worries and tried not to listen too hard to the rumors.

What was our psychological condition? Thomas had been told that we were going on a trip around the world. In Zagreb, however, in the gypsy camp, he had to be told that this was not so, which distressed him quite a bit. When I retired after a turbulent day, to the room I had for myself in my lady friend’s house, I was in a peculiar condition. The thoughts kept milling around in my head in an uncontrollable fashion. What will happen to us? Shall we get to France? Where shall we settle eventually? Will there be war? in that case, what will happen to us? etc. etc. in endless return. This aimless turnover formed in my mind the image of a pot in which noodles are being boiled. They rise, disappear, mill around in endless repetition. That lasted several days, or rather evenings.

When Mrs. Borri returned from Trieste she had bad news. The French consulate had stopped giving any visas and she came back empty-handed. In addition, she told us that Italy looked like on the brink of war. She stayed a few more days with us, then returned to Vienna.

We had found a boarding house where we moved from Zupic. It was on the periphery of Zagreb and we lived there 2–3 weeks, I think. We could use the kitchen and life was less complicated. Part of the day was filled with the daily chores and the children. Lisa had started to walk. I often took Thomas for long walks. He saw something he still remembers. On the street there were people who had suckling pigs on a spit over a fire. The melancholy slavonic street cries are still in my ear.

After the first letdown about Trieste was over we tried to build up other connections. Somebody had recommended a certain employee of a shipping firm who had connections everywhere. Mother, who has the right temperament for such things, plotted with him how to get a French visa.

I forgot to mention that very soon after my arrival I went to see Mr. Bondy, a former friend from Vienna, who was in Zagreb in business. I asked him: should I try to stay in Jugoslavia beyond my three months, or shall I try as hard as possible to get a French

[5]

visa? He strongly advised the latter course, as the police in Jugoslavia was brutal. He thought in France they were better – a big mistake, by the way.

After we had been in the boarding house for a while we got visitors. The widow of my chief had a sister who had a big villa. The two ladies came to see us, in fact, the sister wanted to look us over. Then she offered us two rooms, where we could stay as long as we wanted, and board. She said we would probably feel better, if we paid something for it. We were very happy and moved into the villa. It was in a very good part of the city, where rich people lived. A wonderful house, a big garden and very nice walks very close. We got excellent food, only Thomas behaved so badly (I don’t know why), that he could not eat on the common table. Beside the lady, there was her old mother and her son, about 30 years old, who appeared only rarely. We lived there the rest of our time very pleasantly and without any worries, except the main ones.

One day we were told that there were people asking for us. It was Dr. and Mrs. Halla, who had been on a vacation to the Adriatic and on the way back to Vienna stopped in Zagreb to see us. It was a great joy to have such faithful friends. We spent 1–2 days together and visited a theater. Mrs. Halla dragged a heavy rucksack with toys Thomas had left behind. Dr. Halla gave me all his travel dinars he had let over, which increased my treasury considerably.

Mother’s plotting had finally matured into the following plan. Ostensibly, we wanted to emigrate to Bolivia. In order to get a visa, one had to show a ship ticket there. The steamship line took a down payment for the tickets, which was sufficient to get the visa. For the full amount we did not have. For Bolivia, one has to leave from Liverpool. To get from Zagreb to Liverpool one has to go through Italy, Switzerland, France, Belgium and England. The idea was to interrupt in France and stay there.

Finally, we got the Bolivian visa and then started to collect the transit visas, which was not too difficult – except for the main one – France.

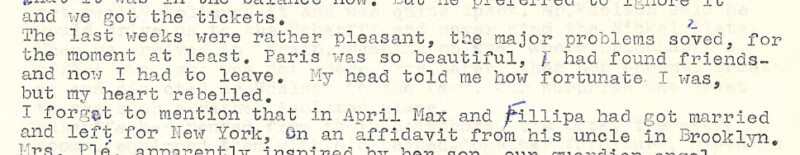

Max kept writing that we should by all means come to Paris – the rest would take care of itself.

Meanwhile, we saw the first ray of hope regarding a final settlement. A friend from Vienna wrote to me that he had gotten out and to Switzerland and received an US affidavit there, which Dr. Dreikurs in Chicago had procured for him from Mr. Hess. But as he was only one and we were four, he felt it fair to cede it to us. I should immediately get in touch with Dreikurs. This was done and led after a long while to our receiving the affidavit. But at that time, we were already in Paris.

The French consul proved extremely unpleasant and entirely unwilling to grant a transit visa. Mother came home in tears and rather desperate. She was in the same condition when she, after the consulate, had to give a language lesson in a family where she was recommended. The man asked her what she had and she told him. Whereupon he said that he knew the French vice consul and would talk to him. And really, this worked and we got a two weeks transit visa.

[6]

It was beginning of November, the leaves in the oak woods had fallen and it had become cool. We completed the travel arrangements and fixed the day of departure. One or two evenings before I went with Lisa in her baby carriage for a walk. Somebody I knew doted on her (slatka mala Lisica) and induced me to take her out and let her walk in the garden, just a few steps. When we came home her nose started to run. Mother was extremely upset and reproached me bitterly. We had to delay the departure a day or two.

Finally, we said good-bye to all the people who had been so wonderful to us and left. I had changed the rest of my money into a 20 $ bill, which I hid, so as not to arrive in Paris completely penniless. On the trip we didn’t see much of the scenery, because the most beautiful places were passed at night.

On the morning of the second day we had reached France and drove straight to Paris. At this time, Lisa became somewhat feverish and had signs of a cold. We arrived in Paris and were met by Max and Fillipa (whom I had never seen) and Leo. They had taken two small rooms in a hotel for us, not far from where they lived. We arrived there and found the hotel small, but decent. The rooms were on the sixth floor with elevator, view on the Bld. Raspail. They were quite suitable for our condition, but rather expensive. We stayed there the whole time till we left.