The Arrival of Hannah Arendt

This film describes the arrival of Hannah Arendt - a Jewish, German-American political theorist and publicist - in New York and her reflections on flight and helping people start over.

Von Anfang an bin ich ins Englische reingeschmissen worden und musste schwimmen. Am Anfang war es ein bisschen komisch, die Leute haben so schnell gesprochen, ich habe nicht immer ganz verstanden, was sie wollten. Wir haben zu Hause Deutsch gesprochen, und mit den Kindern Englisch. Jetzt geht das durcheinander. Im wesentlichen sprechen wir Englisch. Meine ältere Tochter, die jetzt wieder in Europa ist, hat in Europa halbwegs anständig Deutsch gelernt, weil sie dort mit deutschen Familien verkehrt. Die jüngere Tochter spricht ein mörderisches Deutsch. Und mein Junge, den können Sie totschlagen, der Junge ist sechsundvierzig, der spricht kein Wort Deutsch. Mein Junge ist gequält worden in der Schule: Du Nazi! Als kleiner Junge. Und das hat sich ihm in die Glieder gesetzt. Er versteht Deutsch. Wenn er will, kann er’s auch reden. Aber er tut’s nicht. Nun hatte ja die Sprache der Nazis mit dem eigentlichen Deutsch nichts zu tun. Aber ich bin doch manchmal schockiert, wenn ich das Deutsch höre, das heute gesprochen wird. Wieviel Kasernenhof-, ja, Nazi-Idiom in die Sprache reingekommen ist. Oder immer noch drin ist.

Als was fühlen Sie sich heute eigentlich?

Als Amerikaner.

Was bedeutet das?

Nun, dass man zum Land gehört, dass das das Land ist, wo ich wohne, zu dem ich gehöre, wo meine Kinder sind, wo meine Enkel sind, wo man zu Hause ist, mit allem „if“ und „but“. Und ich glaube, dass ein 30. Januar hier nicht passieren kann, auch wenn es Antisemitismus gibt, aber das ist immer noch im Rahmen von Zivilisation und Menschlichkeit. Man kann die Juden genauso viel und genauso wenig leiden wie man Italiener, die Iren leiden kann, die hier Amerikaner geworden sind. Es ist nun mal ein Land, wo sich jeder identifiziert danach, wo er herkommt. Was es in Europa ja nicht gibt.

From the beginning I was thrown into English and had to swim. It was a bit strange at the beginning, people spoke so fast, I didn’t always quite understand what they wanted. We spoke German at home, and English with the children. Now it’s getting mixed up. Essentially, we speak English. My older daughter, who is now back in Europe, learned halfway decent German in Europe because she associates with German families there. The younger daughter speaks a murderous German. And my boy, you can beat him to death, the boy is forty-six, he doesn’t speak a word of German. My boy was tormented at school: You Nazi! As a little boy. And that got into his limbs. He understands German. If he wants, he can speak it. But he doesn’t. Now the language of the Nazis had nothing to do with the actual German. But I am sometimes shocked when I hear the German that is spoken today. How much of the “Kasernenhof” (barracks yard), yes, Nazi idiom has found its way into the language. Or is still in it.

What do you feel like today?

As an American.

What does it mean?

Well, that I belong to the country, that this is the country where I live, where I belong, where my children are, where my grandchildren are, where I am at home, with all the “ifs” and “buts”. And I think that a January 30 cannot happen here, even if there is anti-Semitism, but it is still within the framework of civilization and humanity. You can suffer the Jews as much and as little as you can suffer Italians, the Irish who have become Americans here. It is a country where everyone identifies himself according to where he comes from. Which is not the case in Europe.

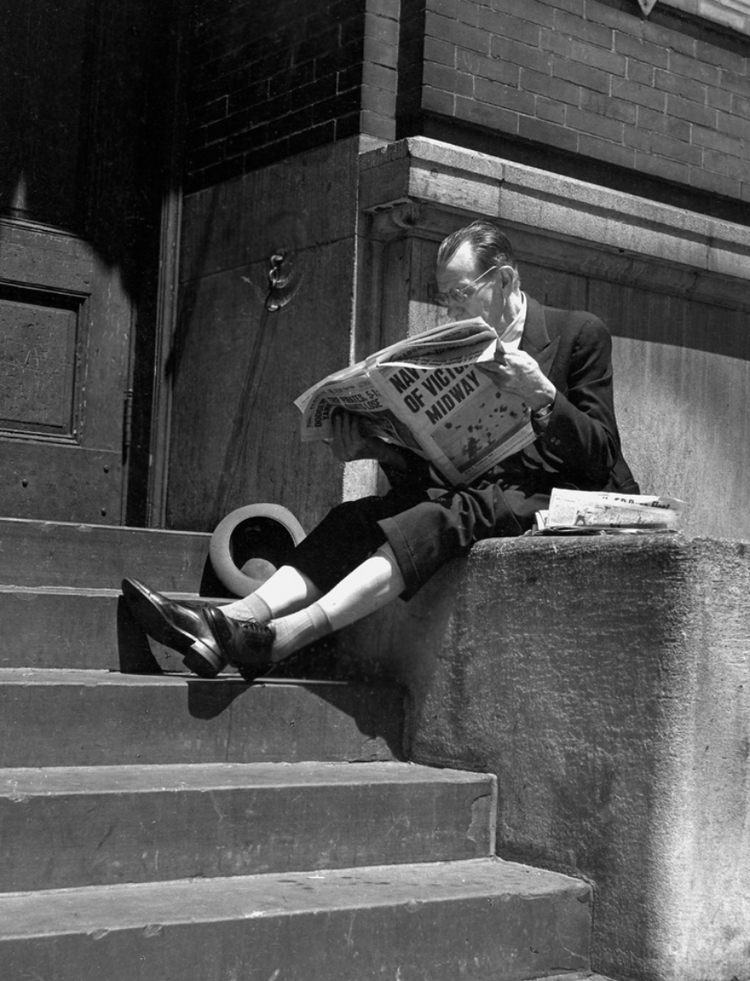

Fred (Fritz) Grubel (formerly Grübel in Germany) was born in Leipzig in 1908. He studied in Leipzig,Frankfurt and received a doctorate in law. He worked in the administration of the Jewish Community in Leipzig.His duties included organizing the emigration of German Jews. He survived a two-month imprisonment in the Buchenwald concentration camp and fled with his family first to England in 1939 and then to the United States in 1940. Since 1966 he was the director of Leo Baeck Institute in New York.

The Leo Baeck Institute is a research library and archive focused on the history of German-speaking Jews. The Institute was founded in 1955 by leading German-Jewish émigré intellectuals including Martin Buber, Max Grunewald, Hannah Arendt and Robert Weltsch, who were determined to preserve the vibrant cultural heritage of German-speaking Jewry that was nearly destroyed in the Holocaust. They named the Institute for Rabbi Leo Baeck, the last leader of Germany’s Jewish Community under the Nazi regime, and appointed him as the Institute’s first President.

Thomas Hartwig, Achim Roscher, 1986: Die verheissene Stadt: Deutsch-jüdische Emigranten in New York. Gespräche, Eindrücke und Bilder. Berlin: Das Arsenal. pp.118-119.

Translation from German to English © Minor Kontor / We Refugees Archive.