New York, 31 May 1941

Dear Günther –

Let’s get to the main points first: Mutt has a Portuguese visa and left France today – praised, drummed and whistled! Channans have visa, but no passage yet. Tout de meme. That leaves Erich C. B. I’ll speak to Nina Rubinstein tomorrow about this matter; Gutmann, in my opinion, won’t pull any punches. Because of the passage of Channan I have to speak to Strauss, because they actually have money, I just don’t know yet how to get it. I do not agree with the “too late” opinion. Misunderstanding. Because apart from that you never know, I tend to believe that there are at least a few months left. […]

I’m afraid there’s nothing to do with Mr. Monsieur’s film past. He’s always worked for Robert Gilbert as an anonymous collaborator. So he never got to know any of the people, because he thought the social side of things was Gilbert’s business.

Earning money: I don’t want to write for the Aufbau. . Won’t and can’t write journalistically at all. I’m still sick and tired of this émigré pack from Paris and I have no intention of getting to know the gentlemen here any better.

Measurements: We saved all our clothes from Paris, which sounds like more than it is, because we haven’t been able to buy anything for 2 years. I don’t have measurements, but Monsieur has your stature and needs a dark suit and some kind of gabardine coat or something like that. I only need a raincoat and maybe a transition coat – and a seamstress to make everything short. Please, laugh!

Otherwise we feel brilliant, even without money. Monsieur gets some support, our room is for Parisian circumstances, especially for the circumstances we have lived in for a year, simply the pinnacle of luxury. NY is like a very big Berlin – that’s fine with me, even though I had become a die-hard Parisian in the last few years. For the time being, I can’t get anywhere, but nothing at all. But I have to read different things. It will be alright. At some point, people will have a lot of fun being with us. Yesterday Kracauers were with us. Ouf …

I don’t think it’s possible that we’re heading west for the time being. We have to see here first and try to get real relationships. Everything else is a luxury. I’m not writing to Feuchtwanger. He has no way of knowing who I am. Ergo.

I’ve only been this happy since Mama’s telegram and Chan’s telegram. That was a terrible worry. Brrrrr. Now Erich is gone – and the whole world can kiss my ass.

I am really looking forward to Hilde and I will write to Mother today. I am very, very touched. But I preferred that you were here to dictate the letter. This really anyway – but then also at all.

I had a message from Eva in Lisbon. How is she?

Monsieur sends his warmest regards. Send me your Jewish novel. I’m responsible for it.

From the bottom of my heart, your H.

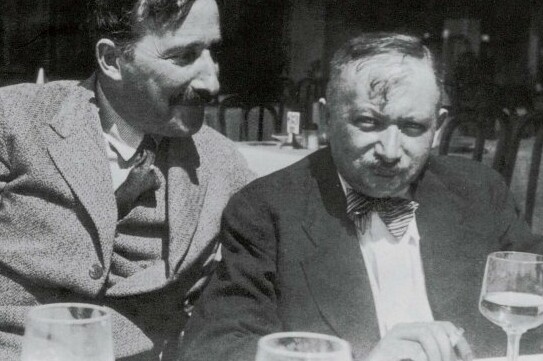

From 1929 to 1937 Hannah Arendt (1906-1975) was married to the German-Austrian philosopher, poet and writer Günther Anders (born Günther Siegmund Stern, 1902-1992). Anders also fled to Paris in 1933, where Arendt followed him a short time later. The marriage finally fell apart in 1937 due to the economic and emotional difficulties of refugeedom in the Quarier Latin. But even after the divorce, they remained friends for a long time. At the time of the letter Arendt had arrived in New York with her second husband Heinrich Blücher, whom she had already met before the divorce from Anders. Anders had already fled to America in 1937.

The letter conveys an absolute relief to have finally escaped the dangers on the European continent in New York. It also proves how much the relief in the now and the individual look into the future is always connected with a look back. Memories of before, of a feeling of home, shape the here in the new home and beloved people are helped by networks, financial aid, etc. to enable them to continue their escape.

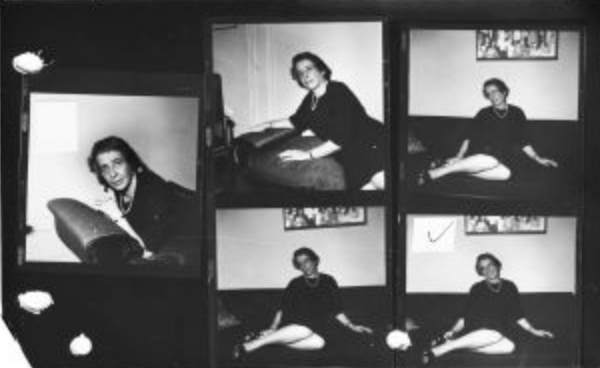

Hannah Arendt was a Jewish German-American political theorist and publicist.

After being detained by the Gestapo for several days in 1933, she fled to France and worked there, among other things, in Zionist organizations that helped Jews to escape. In 1937 she was deprived of German citizenship, which made her a stateless person for almost 14 years. After she was imprisoned for a few weeks in the French internment camp Gurs, she managed to escape from there as well. In 1941 Arendt came to the USA, where she spent the rest of her life and was granted US citizenship in 1951. In her first years in New York she worked as a publicist, editor and contributor to several Jewish magazines (including “Der Aufbau”) and organizations (including the Commission on Jewish Cultural Reconstruction). Under the impression of the experience of flight and arrival that she and other European Jews had had, she also wrote the essay “We Refugees” in the Menorah Journal in 1943. From 1953 to 1967 Arendt taught as a professor at Brooklyn College in New York, at the University of Chicago and at the New School for Social Research in New York.

Arendt, Hannah, 1942; Anders, Günther: Schreib doch mal hard facts über dich. Briefe 1939 bis 1975, Texte und Dokumente, Munich 2016. Pp. 27-29.