Gaus: Is there an exact event in your memory from which you could date your turning to the political?

Arendt: I could mention February 27, 1933, the burning of the Reichstag and the illegal arrests that took place that same night. The so-called protective custody. You know, people were taken to Gestapo cellars or concentration camps. What happened then was monstrous and has often been overshadowed by later things today. This was an immediate shock for me, and from that moment on I felt responsible. In other words, I was no longer of the opinion that you can now just watch. I tried to help in some way. But the thing that led me directly away from Germany – if I have to tell you … I never told anyone because it is completely irrelevant.

Gaus: Tell me.

Arendt: I had the intention to emigrate anyway. I was immediately of the opinion: Jews can’t stay. I had no intention of running around in Germany as a second-class citizen, so to speak, in whatever form. I was also of the opinion that things would get worse and worse. Nevertheless, in the end I did not leave in such a peaceful way. And I must say I had a certain satisfaction. I was arrested, had to leave the country illegally – I’ll tell you about it in a moment – I had an immediate satisfaction. I thought, at least I did something! At least I’m not innocent. I don’t want that kind of talk. Well, the opportunity was given to me by the Zionist organization. I was very close friends with some of the leading people, especially the then president, Kurt Blumenfeld. But I was not a Zionist. Nor did they try to make me a Zionist. At least I was influenced by it in a certain sense; namely in the criticism, in the self-criticism that the Zionists developed among the Jewish people. I was influenced by it, I was impressed by it, but politically I had nothing to do with it. Well, in ’33 Blumenfeld and another man you do not know approached me and said to me: “We want to make a collection of all anti-Semitic statements at a lower level. So let us say teachers’ associations, all kinds of professional associations, all kinds of professional journals: the kind of things that are not known abroad. Organizing this collection, at that time, fell under “horror propaganda,” as it was called. No one who was organized by the Zionists could do that. Because if it blew up, the organization blew up.

Gaus: Of course.

Arendt: That’s obvious. “Do you want to do it?” I: “Of course.” I was very pleased. Firstly, it seemed very reasonable, and secondly, I had the feeling that something could be done.

Gaus: Have you been arrested in connection with this work?

Arendt: Yes. I was exposed. I was very lucky. Got out after eight days, I think, because I – the detective who arrested me, I became friends with him. And he was a lovely guy. He had originally moved from the Criminal Investigation Department to the Political Department. He had no idea. What was he doing there? He used to tell me: “Usually there’s always someone sitting in front of me, I just have to look and then I know what it is. But what am I gonna do with you?”

Gaus: That was in Berlin?

Arendt: That was in Berlin. Unfortunately I had to lie to this man. I wasn’t allowed to bust the organization. I told him fantastic stories, and he always said: “I brought you in. I’ll get you out again. Don’t hire a lawyer! The Jews have no money now. Save your money!” Meanwhile, the organization had gotten me a lawyer. Again, through members, of course. And I sent that lawyer away. Because I relied on this man who had arrested me – such an open, decent face – I relied on myself and thought, this is a much better chance than some lawyer who is just scared after all.

Gaus: You got out and could leave Germany?

Arendt: Of course. I got out, but had to cross the green border illegally, because of course things continued.

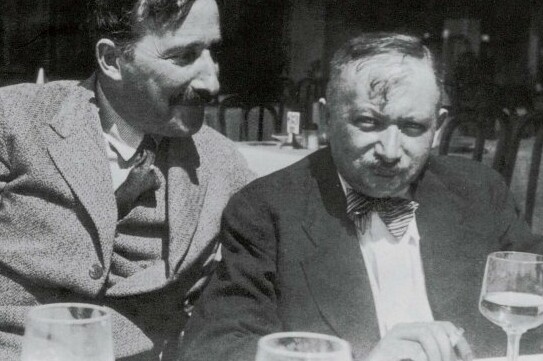

On September 16, 1964, an interview took place between the political theorist Hannah Arendt (1906-1975) and the journalist Günter Gaus (1929-2004) that would become famous. Since 2013, more than one million people have seen the interview on YouTube.

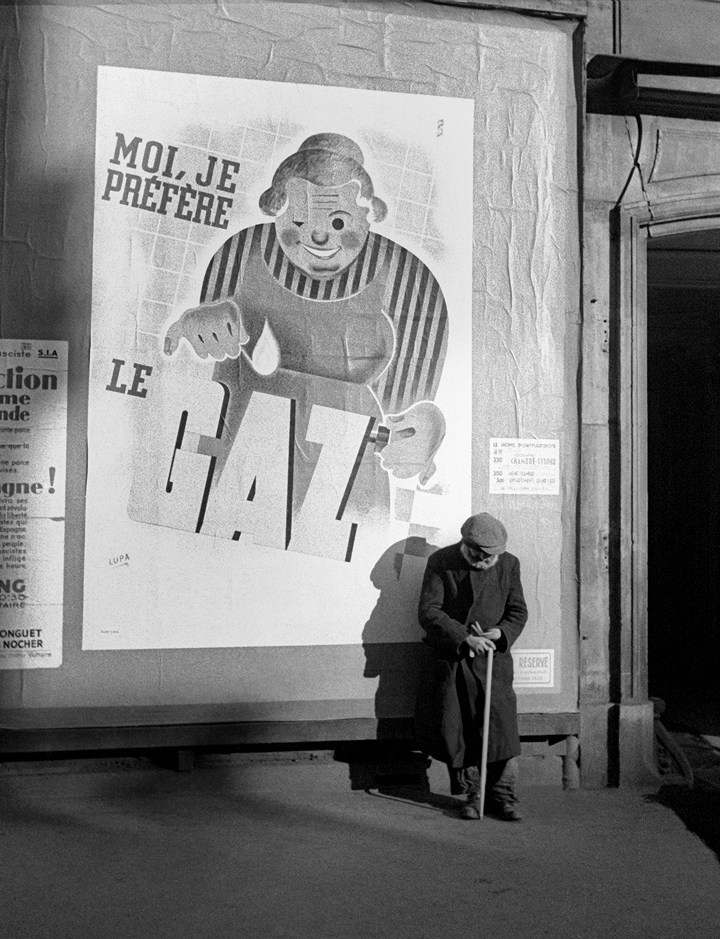

Since Hitler’s seizure of power, Arendt was aware that she would have to leave Germany, but there were concrete key events that prompted her to flee immediately. The Reichstag fire on the night of February 27-28, 1933, and the illegal arrests that took place politicized her immensely and led her to work for the Zionist organization in Germany as part of a documentary project on antisemitism from below. In this context she was arrested. There was no turning back. She left Germany across the green border for Paris, as soon as she was released. This excerpt demonstrates how key events are crucial to the final decision to flee.

Hannah Arendt was a Jewish German-American political theorist and publicist.

After being detained by the Gestapo for several days in 1933, she fled to France and worked there, among other things, in Zionist organizations that helped Jews to escape. In 1937 she was deprived of German citizenship, which made her a stateless person for almost 14 years. After she was imprisoned for a few weeks in the French internment camp Gurs, she managed to escape from there as well. In 1941 Arendt came to the USA, where she spent the rest of her life and was granted US citizenship in 1951. In her first years in New York she worked as a publicist, editor and contributor to several Jewish magazines (including “Der Aufbau”) and organizations (including the Commission on Jewish Cultural Reconstruction). Under the impression of the experience of flight and arrival that she and other European Jews had had, she also wrote the essay “We Refugees” in the Menorah Journal in 1943. From 1953 to 1967 Arendt taught as a professor at Brooklyn College in New York, at the University of Chicago and at the New School for Social Research in New York.

Günter Gaus in conversation with Hannah Arendt; broadcasted on 28 October 1964.

Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J9SyTEUi6Kw

Courtesy of ZDF / ZDF Enterprises GmbH