The Arrival of Hannah Arendt

This film describes the arrival of Hannah Arendt - a Jewish, German-American political theorist and publicist - in New York and her reflections on flight and helping people start over.

Wann haben Sie sich entschlossen, zu emigrieren? Welche Gründe wurden für Sie ausschlaggebend?

Nun das sind eigentlich zwei Geschichten. Die Wurzeln meiner Emigration in die USA geht auf das Jahr 1934 zurück. Auf einen Artikel, den ich in der CV-Zeitung 11“Central Verein-Zeitung. Blätter für Deutschtum und Judentum. Organ des Central-Vereins deutscher Staatsbürger jüdischen Glaubens e.V. Allgemeine Zeitung des Judentums.” Die CV-Zeitung war eine der bedeutendsten jüdischen Wochenzeitungen im deutschen Sprachraum und erschien von 1922 bis zu ihrem Verbot 1938. veröffentlichen konnte, ein ziemlich sentimentaler, nicht einmal guter Aufsatz, erhielt die Redaktion einen Brief von dem Mann aus Chicago, der nach meiner Adresse fragte. Ich habe gedacht: Schaden kann’s nicht, wenn ich antworte. Ein zweiter Brief von diesem Mann war kurz gehalten: Ich weiss nicht, ob Sie alt sind oder jung. Ich weiss von Ihnen gar nichts. Ich weiss nur, dass jemand, der so schreibt, nicht ins heutige Deutschland gehört. Möchten Sie nicht nach Amerika kommen? Ich biete Ihnen ein Affidavit an. Da habe ich dem Herrn zurückgeschrieben, mich bedankt und gesagt: Nein, danke, ich bleibe hier. Daraus hat sich eine lange Korrespondenz entwickelt die mich entnervt hat, weil ich gefühlt habe, der Mann hat ja recht. Das ging so weit, dass ich nicht mehr geantwortet habe, was sehr ungezogen war, aber ich konnte nicht mehr.

Schliesslich, nachdem ich längst aus Deutschland war, erreichte mich über viele Stationen wieder ein Brief von diesem alten Herrn. Er schrieb: Ich weiss genau, warum Sie mir nicht mehr geantwortet haben. Ich möchte Sie nur bitten, mir eine Frage zu beantworten. Sehen Sie es immer noch nicht ein? Da habe ich geschrieben: Ja, ich sehe es ein, aber ich habe keine Möglichkeit. Der nächste Brief brachte mir sein Affidavit. Das wurde vom amerikanischen Konsul in Prag abgelehnt, weil der Mann zu alt, nicht mit mir verwandt war, und sein Bankkonto betrug nur 300 Dollar. Also, das ist ein Märchen für sich. Schliesslich bin ich doch mit dem Affidavit dieses Mannes in die USA gekommen.

Der aktuelle Entschluss, Berlin zu verlassen, fiel Ende ’37. Die Gestapo hatte mir die Pistole auf die Brust gesetzt. Ich verfügte über eine kleine Erbschaft in Pilsen, und ein Bruder meiner Mutter, ein Anwalt, hatte das zu verwalten. Mein Vater, der ein sehr gesetztreuerer Deutscher war, hat dieses Auslandsguthaben sofort angemeldet, so wie es das Gesetz befahl. Daraufhin hat die Gestapo verlangt, dass ich dieses Vermögen ins Reich transferiere. Mein tschechischer Onkel weigerte sich, das Geld herauszugeben. Die Gestapo setzte mich vor die Alternative: Entweder ist das Geld innerhalb einer Woche hier oder Sie wissen, wo wir Sie hinbringen werden. Zwei Tage später war ich weg, in der Tschechoslowakei.

When did you decide to emigrate? What reasons became decisive for you?

Well, that’s actually two stories. The roots of my emigration to the USA go back to 1934. In response to an article I was able to publish in the CV newspaper, 11“Central Verein-Zeitung. Blätter für Deutschtum und Judentum. Organ des Central-Vereins deutscher Staatsbürger jüdischen Glaubens e.V. Allgemeine Zeitung des Judentums.” The CV-newspaper was one of the most important Jewish weekly newspapers in the German-speaking world and appeared from 1922 until it was banned in 1938. a rather sentimental essay, not even a good one, the editors received a letter from the man in Chicago asking for my address. I thought: It can’t do any harm if I answer. A second letter from this man was brief: I don’t know whether you are old or young. I don’t know anything about you. I only know that someone who writes like that does not belong in today’s Germany. Wouldn’t you like to come to America? I offer you an affidavit.

I wrote back to the gentleman, thanked him and said: No, thank you, I’m staying here. From this a long correspondence developed which unnerved me because I felt that the man was right. It went so far that I no longer answered, which was very sassy, but I couldn’t take it anymore.

Finally, after I had long since left Germany, a letter from this old gentleman reached me again via many stations. He wrote: I know exactly why you did not answer me anymore. I would just like to ask you to answer me one question. Do you still not see it? Then I wrote: Yes, I see it, but I have no way. The next letter brought me his affidavit. This was rejected by the American consul in Prague because the man was too old, not related to me, and his bank account was only 300 Dollar. Well, that is a fairy tale in itself. Finally, I came to the USA with this man’s affidavit.

The actual decision to leave Berlin was made at the end of ’37. The Gestapo had put a gun to my cheast. I had a small inheritance in Pilsen, and one of my mother’s brothers, a lawyer, had to administer it. My father, who was a very law-abiding German, immediately declared this foreign asset, as the law ordered. The Gestapo then demanded that I transfer these assets to the Reich. My Czech uncle refused to hand over the money. The Gestapo gave me the alternative: either the money is here within a week or you know where we will take you. Two days later I was gone, in Czechoslovakia.

Hilde Marx (born November 1, 1911 in Bayreuth) was a German-American poet, writer and journalist. She is one of the authors whose writing career was only just beginning when the National Socialists came to power in Germany in 1933, and was immediately prevented by them. As a Jew, however, she was already affected by anti-Semitism before that. She already experienced what it meant to be Jewish at the Humanist Gymnasium. After graduating from high school in 1931, Hilde Marx began studying journalism, theater and art history in Berlin. After five semesters, however, she was forcibly de-registered, as Jews were no longer allowed to attend universities. While she was still able to publish for newspapers at “Ullstein,” “Mosse” and the “Berliner Tageblatt,” this was no longer possible after their “Aryanization”. She was left only with Jewish publications, such as “Die Monatsblätter des jüdischen Kulturbundes in Deutschland,” “Die Jüdische Revue,” “Das Jüdische Gemeindeblatt,” and above all the “C.V.-Zeitung”. 11“Central Verein-Zeitung. Blätter für Deutschtum und Judentum. Organ des Central-Vereins deutscher Staatsbürger jüdischen Glaubens e.V. Allgemeine Zeitung des Judentums.” Die CV-Zeitung war eine der bedeutendsten jüdischen Wochenzeitungen im deutschen Sprachraum und erschien von 1922 bis zu ihrem Verbot 1938.

She did not think about emigration for a long time, but when the Gestapo threatened her with imprisonment in a concentration camp in 1937, she fled to the Czech Republic, and from there she managed to leave for the USA a year later. In November 1938 she arrived in New York. She worked in various jobs: as a nurse for the elderly, a saleswoman, a nanny and a gymnastics trainer. However, in addition to these demanding jobs, she also tried to gain a foothold as a writer in the USA. To this end, she asked the American Guild for German Cultural Freedom for help.

In 1943 she received American citizenship. In America she continued to perform as a lecture artist, with her own “One woman show” in which she combined serious with light-hearted, Jewish with Christian traditions.

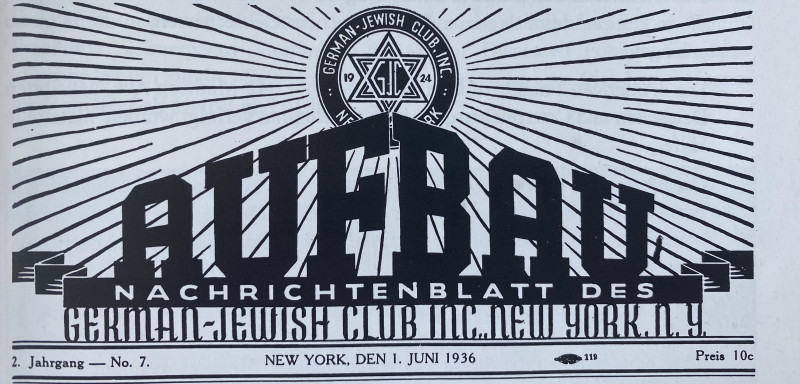

In 1951, a final volume of poems from 1938 to 1951 was published under the title “Bericht,” which incorporated her experiences as an exile. She became a member of Auslands-PEN and, from the 1960s on, was an editor of “Aufbau”, 22“Aufbau”: In 1934, the first “Aufbau. Nachrichtenblatt des German-Jewish Club, Inc., New York” appeared. Initially more a club and advertising organ, the “Aufbau” soon became a news sheet about the everyday life of German (not only Jewish) emigrants in exile. This meant advice on legal matters, explanations of the New York subway system, language courses and job vacancies, tips on dealing with authorities, etc. Oskar Maria Graf and Nelly Sachs, Lion Feuchtwanger and Thomas Mann, Mascha Kaléko and many others wrote here. for which she wrote primarily theater and film reviews, as well as short biographies of Jewish emigrants. She also worked for other newspapers, such as “This Day from St. Louis,” “The Chicago Jewish Forum,” the state newspaper and “Herold from New York”.

Henri Jacob. Hempel (Hrsg.),1983: Wenn ich schon ein Fremder sein muß… Deutsch-jüdische Emigranten in New York. Frankfurt/M.-Berlin-Wien: Ullstein Verlag, p. 46.

Translation from German to English © Minor Kontor / We Refugees Archive.