En 1936, j’ai eu de gros problèmes pour trouver du travail car comme j’avais la nationalité espagnole, je n’arrivais pas à obtenir un livret de travail. Pour se faire naturaliser, il fallait de l’argent car cela coûtait cher de faire traduire les papiers espagnols des parents (actes de naissance, de mariage, etc.). Heureusement, le mari de ma sœur aînée Felicidad travaillait à la Chambre de commerce espagnole à Paris et m’a établi un premier certificat de travail pour trois mois. Ensuite je suis entrée comme manutentionnaire dans une boîte, Debriz Spiritueux, avenue Wilson et avec leur certificat de travail, j’ai pu me faire établir une carte d’identité d’étranger à la préfecture.

In 1936, I had great difficulty finding work, because I had Spanish nationality, I could not get a work permit. To become naturalized I needed money, because it was expensive to translate my parents’ Spanish papers (birth certificates, marriage certificates, etc.). Fortunately, the husband of my older sister Felicidad worked at the Spanish Chamber of Commerce in Paris and issued me a first work certificate for three months. Then I started as a warehouse worker in a company, Debriz Spirits, Avenue Wilson, and with her work certificate I was able to obtain a foreigner’s identity card from the prefecture.

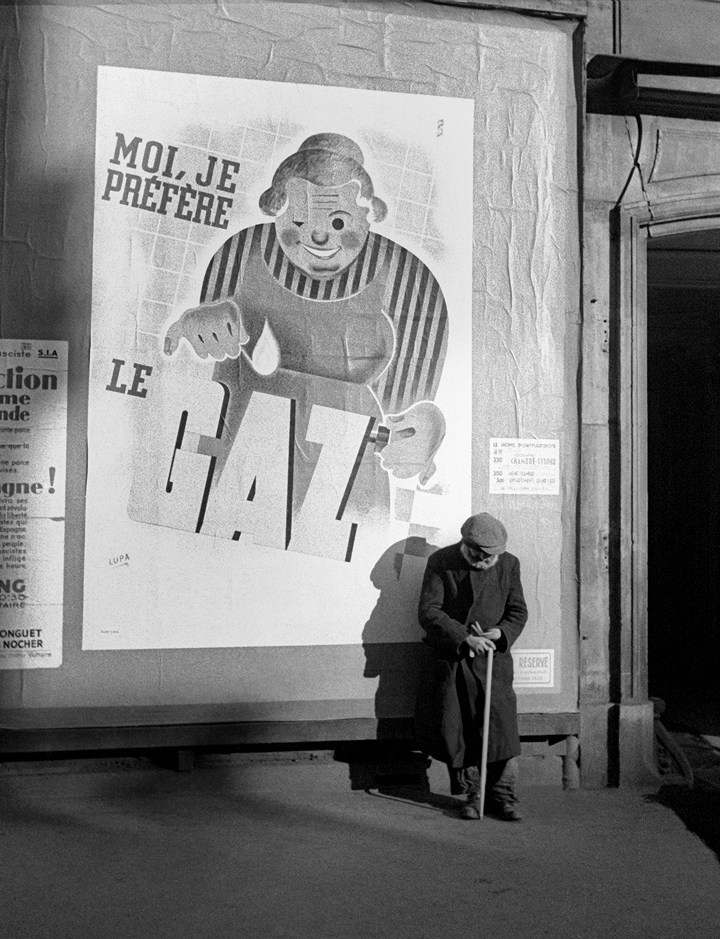

In the first half of the 20th century, the so-called “Little Spain” emerged in the Parisian suburb of La Plaine Saint-Denis. In 1931, Spaniards made up the largest migrant community in La Plaine Saint-Denis with 4.5 percent of the total population.

Various Spanish migrants had settled in Saint-Denis, Saint-Ouen and Aubervilliers in the course of three distinct migratory movements. So-called “economic migrants” shaped the decade of the 1920s. After the uprising in Asturias was crushed at the end of 1934, political refugees in particular began to arrive in the Parisian suburbs, and their number rose to about 1.5 million by 1950 after the defeat of the Republican camp in 1939. Another generation of Spanish “economic migrants” followed between 1955 and 1970.

The connection back to Spain remained intact for many even after their migration. For example, when the Civil War raged in Spain, some ethnic Spanish men aged 18 to 46 left the Plaine Saint-Denis to return to Spain to fight in the Republican camp. Those who stayed in “Little Spain” organized support networks for communists or anarchists.

The reception experience for Spanish migrants differed according to the French migration regime. The latter in turn changed with the economic and political situation in France but exclusion and discrimination dominated the lives of many no matter when they arrived. For example, when, in early 1939, Spanish republican refugees from the Civil War exited for France, many of whom migrating to Paris and the surrounding areas, it became all too obvious that France had changed from a country of refugees to a country of forced transit. For although the French authorities had been very well prepared in the late 1930s to accept Spanish civil war refugees “humanely,” domestic, foreign policy and economic developments obviously spoke against this: immigration was to be severely restricted under the right-wing government of Édouard Daladier, making it more difficult for refugees to remain in France.

Interview excerpt with Angelines Koulikoff, née Martinez, conducted by Natacha Lillo, lecturer in Spanish civilization at the University of Paris-Diderot (Paris 7), on December 13, 1999 and March 29, 2000 in Saint-Denis.

Natacha Lillo, La Petite Espagne de la Plaine Saint-Denis (Paris: Autrement, 2004).