Gaus: When you left Germany in 1933, you went to Paris, where you worked in an organization that tried to place Jewish youth in Palestine. Can you tell me something about that?

Arendt: Yes, you know […] that would lead me too far. I want to tell you what it was: It was the Youth Aliyah, an organization that was founded in Germany at the instigation of Recha Freier, already in ’32, and then in ’33 of course it became very big and was then led by Henrietta Szold in America, organizationally, Recha Freier in Germany, Henrietta Szold then in Palestine. This organization brought Jewish youths and also children – but children, I had nothing to do with that – between thirteen and seventeen years of age from Germany to Palestine and accommodated them there in the Kibutzim. So I know these settlements relatively well.

Gaus: And from a very early time.

Arendt: From a very early time; at that time I had a very great respect for how this thing went on. The children received vocational training, retraining. Well, in France, the situation was that when the refugee children were fourteen years old and finished school, they didn’t get a work permit or a vocational training permit. And as a result, certificates were diverted to France for refugee children. And here and there I smuggled Polish children into France, because this naturally resulted in preferential treatment for those who came from Germany. And I did this with great pleasure, it was a regular social work, educational work. One had large camps in the countryside where the children were prepared, where they also had hours, where they learned agricultural work, where above all they had to gain weight. They had to be dressed from head to toe. They had to cook for them. Above all, one had to obtain papers for them, one had to negotiate with their parents – and above all, one had to get money. That was also largely left to me. I worked with French women. So that was roughly the activity. But now, the decision to take over [this work] from the previous activity: do you want to hear it or don’t you want to?

Gaus: Please.

Arendt: You see, I came from a purely academic background. And in this respect the year ’33 made a very lasting impression on me. First of all positive and secondly negative – or I would like to say: firstly negative and secondly positive. People often think today that the shock of the German Jews in ’33 can be explained by the fact that Hitler seized power. Well, as far as I and people of my generation are concerned, I can say that this is a curious misunderstanding. It was, of course, very bad. But it was political. It was not personal. That the Nazis are our enemies – my God, please, we didn’t need Hitler’s seizure of power to know that! For at least four years, that was completely obvious to anyone who was not moronic. That a large part of the German people was behind it, yes, we knew that too. Surely we could not have been shocked by that in ’33.

Gaus: You mean, the shock in 1933 was that it turned from the general political to the personal?

Arendt: No, not even once. Or: that too. First of all, the generally political became a personal fate, as long as one went out. But secondly, you know what Gleichschaltung is. And that meant that friends became equal! The problem, the personal problem was not what our enemies did, but what our friends did. What was going on at that time in the wave of conformity, which was quite voluntary, at least not under the pressure of terror, [was] mainly because of the sudden departure, it was as if an empty space formed around you. Well, I lived in an intellectual milieu, but I also knew other people. And I could see that among the intellectuals this was the rule, so to speak; and among the others it was not. And I have never forgotten that story. And with one thing I thought at the time – always a bit exaggerated, of course – I left Germany: Never again! No, I will never again touch any intellectual history. I want nothing to do with this society. Of course, I didn’t think that German Jews or German Jewish intellectuals, if they had been in a different situation from the one they were in, would have behaved much differently. I was not of that opinion. I was of the opinion that it had to do with this profession. I am speaking today in the past. I know more about it now than I did then…

Gaus: I was about to ask you: Do you still believe that?

Arendt: Yes, you know, not in this sharpness anymore. But the fact that it’s in the nature of all these things, that you can come up with something for everything […] You see, no one has ever resented the fact that somebody put himself on an equal footing because he had to take care of his wife and child. The worst thing was that they really believed in it! For a short time, some for a very short time. That is to say: they thought of something about Hitler; and some of them were incredibly interesting things, weren’t they! Very fantastic and interesting and complicated things. And things that are above the ordinary. I found that grotesque. In other words, they fell into their own trap, I would say today. Not, that’s what happened. I didn’t overlook it then.

Gaus: And that’s why, if I understand you correctly, a special value for you was to move from these circles, which you wanted to say an absolute farewell to at the time, […] from academic work to practical social work?

Arendt: Yes, now the positive side is this: I said one sentence over and over again at that time, which I remember: “If you are attacked as a Jew, you must defend yourself as a Jew.” Not as a German or as a citizen of the world or human rights or something. But quite specifically: How can I, what can I do? Secondly: Now I want to organize myself in any case. For the first time. And organize with the Zionists, of course. They were the only ones who were ready. I mean, with the assimilationists, it wouldn’t have made any sense. I really never had anything to do with that, by the way. I had dealt with the Jewish question myself before. The “Rahel Varnhagen” was ready when I left Germany. And there the Jewish problem plays a role.

Gaus: This was a research project commissioned by the Notgemeinschaft (German Relief Society).

Arendt: The German Relief Society, yes, I had the scholarship from the Notgemeinschaft, the usual scholarship. I also wrote this in the sense of: “I want to understand.” It wasn’t my personal Jewish problems I was discussing. But now it had become my own problem. And my own problem was political. Purely political! I wanted to get into practical work and – I just wanted to get into Jewish work. And, in this sense, I then oriented myself in France.

Gaus: Until 1940.

Arendt: Yes.

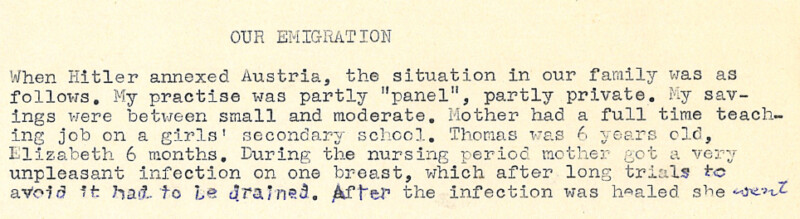

On September 16, 1964, an interview took place between the political theorist Hannah Arendt (1906-1975) and the journalist Günter Gaus (1929-2004) that would become famous. Since 2013, more than one million people have seen the interview on YouTube. In this excerpt Arendt talks about her work for the Zionist organization Youth Aliyah, for which she began working in Paris. The organization tried to prepare Jewish youth for emigration and life in Palestine and to provide the necessary money and papers. For Arendt, who until then had worked only academically, the step to political activism and practical “social work” after her escape was a big, but instinctive one. It was not only a matter of actively saving lives, but also of defending oneself as a Jewish person and thus of offering concrete resistance. Understanding the phenomena that shaped her life, fascism/totalitarianism, statelessness and refugeedom, and the interconnectedness to her Jewishness, would occupy her all her life.

Hannah Arendt was a Jewish German-American political theorist and writer.

After being detained by the Gestapo for several days in 1933, she fled to France and worked there, among other things, in Zionist organizations that helped Jews to escape. In 1937 she was deprived of German citizenship, which made her a stateless person for almost 14 years. After she was imprisoned for a few weeks in the French internment camp Gurs, she managed to escape from there as well. In 1941 Arendt came to the USA, where she spent the rest of her life and was granted US citizenship in 1951. In her first years in New York she worked as a publicist, editor and contributor to several Jewish magazines (including “Der Aufbau”) and organizations (including the Commission on Jewish Cultural Reconstruction). Under the impression of the experience of flight and arrival that she and other European Jews had had, she also wrote the essay “We Refugees” in the Menorah Journal in 1943. From 1953 to 1967 Arendt taught as a professor at Brooklyn College in New York, at the University of Chicago and at the New School for Social Research in New York.