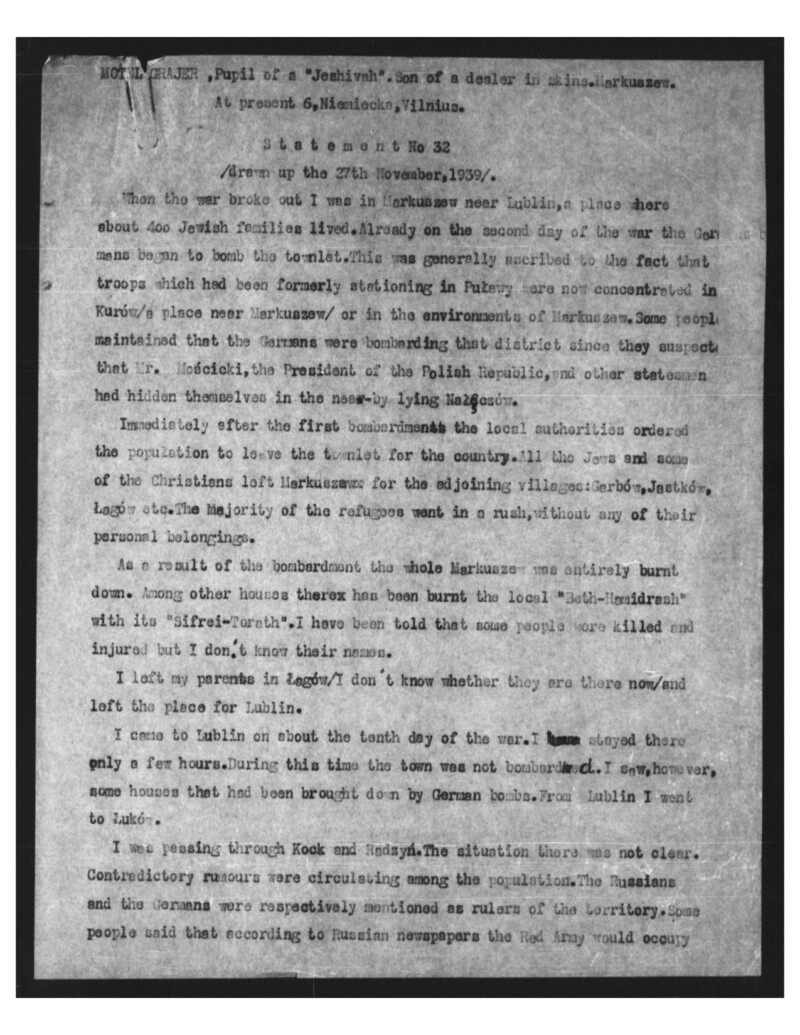

MOTEL GRAJER, Pupil of a “Jeshivah.” Son of a dealer in skins. Markuszew.

At present 6, Niemiecke, Vilnius.

Statement No 32

/drawn up the 27th November, 1939/.

When the war broke out I was in Markuszew near Lublin, a place where about 400 Jewish families lived. Already on the second day of the war the Germans began to bomb the townlet. This was generally ascribed to the fact that troops which had been formerly stationing in Puławy are now concentrated in Kurów /a place near Markuszew/ or in the environments of Markuszew. Some people maintained that the Germans were bombarding that district since they suspected that Mr. Mościcki, the President of the Polish Republic, and other statesmen had hidden themselves in the near-by lying Nałęczów.

Immediately after the first bombardments the local authorities ordered the population to leave the townlet for the country. All the Jews and some of the Christians left Markuszew for the adjoining villages: Gerbów, Jastków, Łagów etc. The majority of the refugees went in a rush, without any of their personal belongings.

As a result of the bombardment the whole Markuszew was entirely burnt down. Among other houses there has been burnt the local “Beth-Hamidrash” with its “Sifrei-Torath.” I have been told that some people were killed and injured but I don’t know their names.

I left my parents in Łagów /I don’t know whether they are there now/ and left the place for Lublin.

I came to Lublin on about the tenth day of the war. I stayed there only a few hours. During this time the town was not bombarded. I saw, however, some houses that had been brought down by German bombs. From Lublin I went to Łuków.

I was passing through Kock and Radzyń. The situation there was not clear. Contradictory rumours were circulating among the population. The Russians and the Germans were respectively mentioned as rulers of the territory. Some people said that according to Russian newspapers the Red Army would occupy

[Page 2]

the whole territory up to the river Vistula.

A tragedy was told to have occurred in the family of Mr. Morgensztern, the Rabbi of Kock. His brother, the Rabbi of Włodawa, was in Kock when the Germans entered the place. One day, at a moment when the Rabbi was leaving his house he was shot at by the Germans. Some people said he had been killed, others that he had been badly injured.

We decided to avoid towns and thus we went through fields and sideways. That is why I can’t say what the towns looked like on those days.

My way to Luków took a long time. My feet hurt. I was worn out and dragged myself from one village to another. At night time we used to sleep in the houses of the peasants. The attitude of those people was full of understanding of our situation. Now and then we used to get not only a place for the night – free of charge – but some bread too.

In one of the villages a nice-looking German strom-trooper was asked by a Christian former railway-employee: “Why is it so that innocent people are being beaten and murdered?” The German replied: “I can’t help it. This is war.” The Christian asked him for a cigarette. The German gave him one and lit it for him.

We took a rest in an adjoining garden. Suddenly we saw the above mentioned storm-trooper coming up together with a few others to the house of the owner of the garden. The Germans shot at the house and killed one girl. We went on. The above mentioned Christian told me that he hade seen with his own eyes the following episode: A German stopped passing-by people and asked for their names. Some of the people that were not of a typical Jewish physiognomy declared Polish names. When it was then stated by the Germans in the documents of each of these men that some of them had declared a Christian name instead of their Jewish ones – the respective people were shot down.

I arrived at Łuków on the fourth day of “Sukoth.” The Russians ruled the town. I met one of the local inhabitants whose name I don’t remember. In reply to his question I told him how I had got out of my native place and what I had

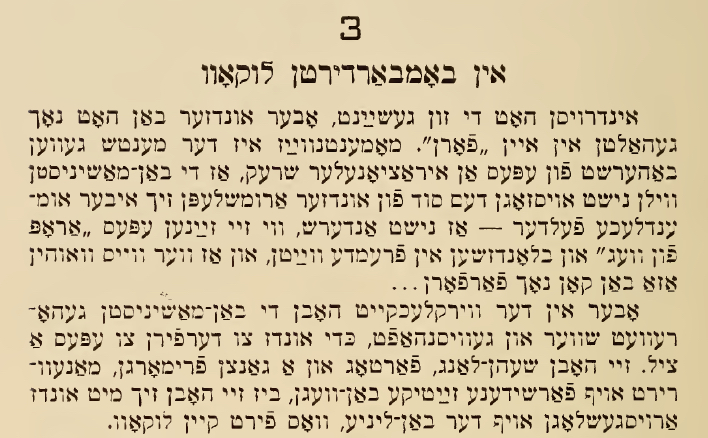

[Page 3]

been through. He invited me to his house, gave me food, a place to sleep, and did not want to take the money that I offered him.

Since the Russian papers kept writing that the Red Army would occupy the whole territory up to the river Vistula, and thus Puławy would be within the Russian frontiers I decided to go back to my parents, in the direction of Lublin. No trains were available. Lublin was in German hands. I went afoot. Passing through Suchowola I saw a group of Polish soldiers that had hidden themselves there. They used to shoot down every Jew they met since they were angry with the Jewish population for their hearty welcome of the Russians.

When I tried to go on I was stopped by Russian patrols: eventually I went back to Łuków. Here I came again to the man that had formerly been my host. /His first name was Shmul-Elia/. He tried to persuade me to go to Brześć nad Bugiem since the Germans were expected to occupy the whole country up to the river Bug.

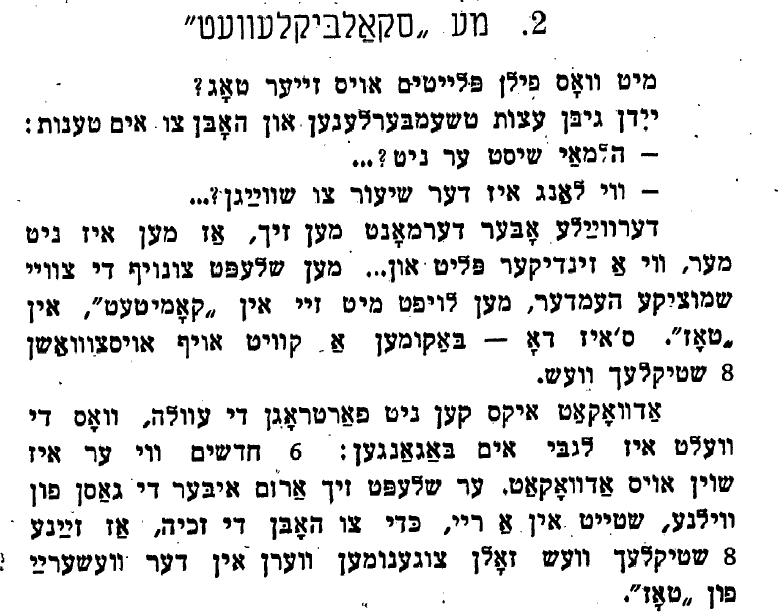

My host told me the story of German outrages committed during the first stay of the Germans in Łuków. Hundreds of young Jews, mostly religious ones, had been sent off to a concentration camp in Ostrów-Mazowiecki. Among others, my host’s son had been sent off too /he was a pupil of Rabbi Elchanan Wasserman of the “Jeshivah” of Baranowicza/. He had been caught when he was on his way home from the Synagogue. He had been painfully beaten and tortured and had not been given any food. On Jom Kippur /Doom’s Day/, however, he had been made to eat. My host’s daughter tried to secure his release but her laments and crying were in vein. She was beaten as well. She returned home without her brother.

My host’s brother had been seized too. His wife wanted to let him have some bread but the Germans did not let her in and began to beat her. Her husband, however, managed to escape: when the seized men were driven through a forest he succeeded in hiding in some thick bushes.

The Germans had used to go from house to house and drag out Jews. They had been sent off to the camp in such a state as they were found at the moment

[Page 4]

of their capture. A Jewish baker had been taken from his bakery: he had his white coat on. Many of the people that had been driven to the camp were shot down under the pretext of their trials of escape. Only those ment that had been hidden in the cellars, sticks and similar places had managed to escape this tragic fate.

The Germans used to shoot not only at the “escaping” men. In the towns they had been shooting at Jews in the streets. Among others the old “Gabbi” of the local “Talmud-Tora” had been shot down in from of the “Talmud-Tora.”

Many houses had been demolished by German bombardment. The streets had been full of ruins and demolished houses. At the Międzyrzecke street alone where mostly Jews had been living 8–10 houses were destroyed.

Apart from what my host told me there were stories that he had heard from the refugees that had been living in his house before I came. Those refugees were of Łódż, Warszawa, Radom. Their stories are difficult to relate within the limits of this statement.

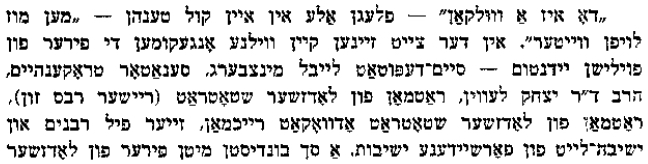

Just at the time when we were discussing those matters people rushed in into my host’s house with the joyful news that his son had just come back. The house became full of joy. The stories of this men were unraderable. Jews of all the surroundings were together with him in the camp: from Węgrów, Siedlce, Sokołów, Mińsk Mazowiecki, etc. The majority were young religious Jews. They were scolded and beaten by the Germans who cut off the Jews’ beards and made them work hard.

Since it was difficult for me to give up the idea of seeing my parents I decided to go to Brześć nad Bugiem.

In the meantime, however, it was learned that the Russians were to leave all the territory up to the river Bug. The communists /in particular the Jewish ones/ advised the population to leave the places together with the Russians. They said that the Germans would come on “Symhat-Tora” already. People were panic stricken. They rushed out of the place in an undescribably chaos. The trains were full. Roads as well. People lost their families, left their belong-

[Page 5]

ings etc.

I got into a goods-train. The carriages were full. People were simply hanging and clutching what one could. There were among them inhabitants of Łuków as well as refugees.

I arrived at Brześć nad Bugiem on the eve of “Hashana-Raba”. I was hungry and exhausted. At the railway station I met some friends of mine of my “Jeshivah”: Haim Wajtman, Simcha Weissman, Jozek Weissman, Jankiel Mandelbojm /a pupil of mine/, all of them of Białe Podlacka. There were some of Kock /of the Kamieniec “Jeshiva”/, of Lublin /of the “Jeshiva” of Międzyrzec/ and of other places. all of these people were running away from the Germans, and told heartbreaking stories.

We decided to go up to the town. We strolled over the streets for several houses. Everywhere there wer to be seen ruins, destroyed houses, broken glass etc.

Accidentally we met in the street a cousin of min, Moshe Aaron Felc of Markuszewo. He had been on duty with a cavalry-regiment at Białystok. He told me that almost the whole regiment had been lost and that only several people including himself, had been saved. My cousin had some money, so we queued up and eventually got some bread. He brought me to the premises of “Mizrahi”: there were already there many Jewish soldiers. They wanted to get back to their families. Some of them wanted civil dresses. I gave a suit and a shirt to my cousin, and the friends of mine of the “Jeshiva” gave what they could to the soldiers. I parted with my cousin and went by train to Pinsk. I intended to go to the “Jeshiva” “Bejt-Josef” where I had once learned and had some friends.

I met many refugees in the train. Each of them was full of undescribable stories.

A man of Węgrów related that the Germans had shot the local Rabbi there. Another man of the same town related that on “Jom Kippur” /Doom’s Day/ the Germans ordered all the Jews to leave the Synagogue and to gather at a wall, where they were to be shot. The Jews were then ordered to count up to three. Many people fainted, the cries were heartbreaking, some of the men began

[Page 6]

to say the death prayer /”Vida”/. Eventually the Germans didn’t bring their threat through. The arms were shot but the Germans aimed above the heads of the men.

People from Brześć nad Bugiem said that at the beginning the situation in the town had not been bad. The later, however, the worse it was. When i was learned that the Russians would take over the whole Polesie – the Germans began to persecute the Jews, to rob their shops etc. Some Germans entered the house of the local Rabbi Syha-Zelig and set to cutting off his beard. They left a part of it and eventually asked money for the “job” they had done. The Rabbi had to give them the money.

A man of Międrzyrzec related that the Germans used to come to the Jewish houses at night time, to rob and take away anything they liked, and to drag out the Jews and send them off in an unknown direction.

The whole way of the train was marked by broken telegraph-poles, destroyed and burnt houses, ruins, burnt woods and crosses over new tombs.

In the train I saw a man that seemed familiar to me. I couldn’t, however, remember whether and where I had met him before. The men approached me and said: “No wonder you don’t recognize me. I was old and now I have been made young.” It appeared that it was an old “Hasid” of Siedlec who had his gray beard cut off by the Germans.

In Pinsk I met many colleagues of the “Jeshiva”. Each of them had many stories to tell of the horrors of the Germans.

I have remained in Pinsk in the “Bejt-Josef Jeshiva” for a fortnight. Pinsk has not suffered very much. A bomb had fallen at Boczna str., near the Kerliński cemitary [sic!], and hit a house near the butcher’s Kapłan. This place is close to the District Hospital, and it was generally believed that the Germans aim was this very Hospital. Another bomb hit a Jewish house at Traugutta str. and cut it into two. The total number of the victims at Pinsk did not exceed 7 or 8.

I left Pinsk and came to Vilnius, since I expect that from here it will be easier to emigrate to America where I have got my relatives. In Vilnius I met

[Page 7]

my brother Shlojma-Lejzer which has come together with other pupils of the “Bejt-Josef Jeshiva” of Białystok.

Here are the addresses of my uncles:

- J. Greer, 2928 Fullerton Ave., Detroit Mich., U.S.A.

- R. Greer, 728, Tuscarora, Vindsor Oat, Canada.