Ekaterina Aygün, Metromod

How did the Russian-speaking refugees end up in the city?

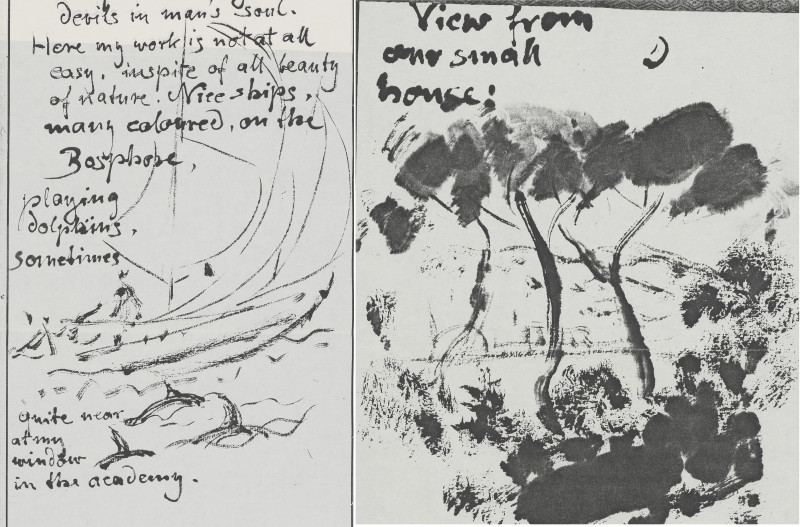

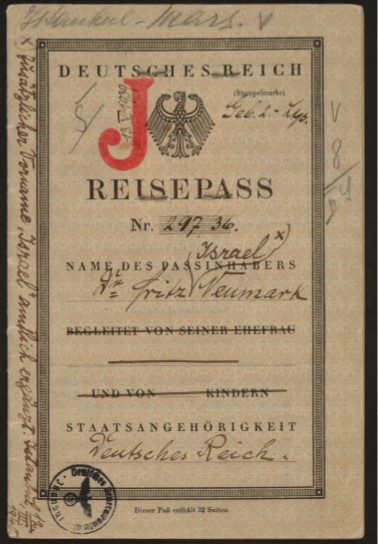

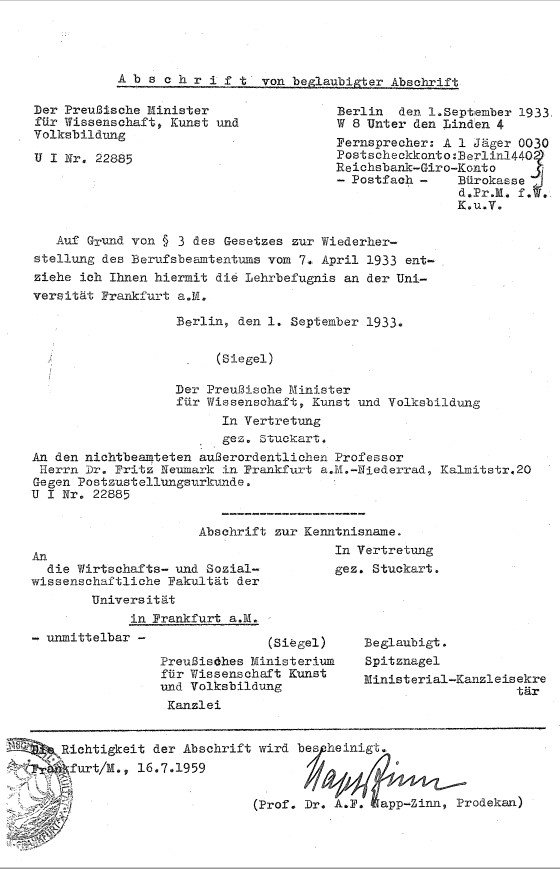

At the beginning of the 20th century, first, a revolution broke out in the former Russian Empire, and then a civil war of such magnitude that for many of the local people it was necessary not only to flee urgently somewhere but also for some time (as it turned out, forever) forget about their routine rhythm of life. Being a geographically close city that could be relatively easily reached by water from Southern “Russia”, Constantinople/Istanbul has been occupied since November 1918 by Allied troops that were favorably disposed toward the Russian refugees. This allowed the newcomers to settle in the city on a previously unseen scale. Fleeing in Istanbul, they tried to save their own lives, but, at the same time, often doomed themselves to unemployment, beggarhood, hunger and diseases, because after the First World War the life in the city was already difficult enough even before their arrival. At the time Istanbul often served as a “transit point”: after living in the city for a maximum of one year and receiving a visa to the desired country, wealthy people left. Another part of the Russian-speaking refugees left in 1923 (in the case of artists, mainly to the US), after Atatürk came to power. It should be noted that for many of them his victory was far from being a festive occasion: living in the Greek quarters, the Russians were afraid of massacres and arson attacks. In addition, they were extremely worried about the established good diplomatic relations of the new Turkish government with the Bolsheviks, and therefore they were in no hurry to obtain Turkish citizenship. Another part of the Russian-speaking refugees left the city in 1927-1928 since the condition of changing the nationality was finally and irrevocably set before those who wanted to stay. Many, for one reason or another, did not want to accept the citizenship, yet they could not return to their homeland because it was dangerous or impossible – so, they had to move once again to other, sometimes very faraway countries including Brazil and Argentina. By 1930, the ranks of the Russian-speaking refugees in Istanbul had significantly thinned. Those who remained in the city can be conditionally divided into two groups: those who for financial or other reasons had nowhere else to go, and those who managed to find a use for their knowledge and talents in a particular field.

Russian-speaking artistic milieu in the city in the 1930s

The following lines from a magazine article of 1934 (the article was found by independent researcher Marina Sığırcı in one of the private archives) give the idea of how the life of the Russian émigrés in Istanbul in the 1930s changed if one compares it to their life in the city in the 1920s: “Currently, there are several Russian officers in the command staff of the Turkish army, Russian engineers built buildings upon their own projects in Istanbul, in Angora [Ankara], Russian physicians have the right to work freely. But in general, the situation is bad, very bad. There are no more Russian clubs, no associations, no public gatherings in Istanbul anymore. Almost all Russians in Turkey are concentrated in Istanbul, they all live in their family circles”. The author of these lines, a certain Konstantin Stamati, was absolutely right: the absence of the Russian unions and clubs in the city, which, like any other “network”, allowed refugees to exchange ideas and work in groups, feeling the support of like-minded people, did not have the best effect on the Russian-speaking community and especially its artists. After the dissolution of the Union of Russian Painters in Constantinople (1923) and the closure of Russian clubs one after another (by 1930, all the main Russian clubs in Istanbul had ceased to exist), where artists were engaged in creating posters, programs, decorations, costumes, and also exhibited their works and staged performances, most of the émigré artists left the city. It can be assumed that those leaving were driven not only by the unwillingness to become subjects of the Turkish Republic but also (and most likely primarily) by the fear of working in a “vacuum”, without social interactions and professional growth, as the local artistic environment, even in the late 1920s, could hardly be called vibrant (at least if one compares it to the artistic environment in Paris or New York): local people were not very familiar with spending time looking at art at the exhibitions (not to mention purchasing of the artworks), starting from 1923 Istanbul stopped to be the only art center in the country, and the first gallery in the city didn’t open until 1950. Also worth highlighting is the fact that after the formation of the Turkish Republic patriotic topics were in vogue which for some of the émigré artists from the former Russian Empire might not have been very congenial.

In the 1930s, the few major exhibitions that were organized in the city were mainly held at the Galatasaray High School. Judging by the lists of participants, not so many subjects of the former Russian Empire took part in them, the fingers of one hand are enough to count. All of them were former members of the Union of Russian Painters in Constantinople (1921/22-1923) and artists who managed to fill a niche in the city. Among them were, firstly, Nikolai Kalmykoff from Kharkiv, a painter who created murals for domestic establishments, cinemas in Beyoğlu (in this sense, acquaintance with İpekçi brothers was beneficial) and the opera house in Kadıköy; secondly, Nikolai Peroff from the Ryazan region (Dolginino), a painter who over a long period worked as a scene designer of the Istanbul Theater at the invitation of Muhsin Ertuğrul; thirdly, the sculptor and painter of Polish origin Roman Bilinski from L’viv, who organised at least two solo exhibitions and left the city in 1936; fourthly, the sculptor Iraida Barry from Crimea and the painter Rakhman Safiev/Safief (Nikolai Kalmykoff’s apprentice and friend) from today’s Azerbaijan, who, due to the circumstances and their age, were educated already in Turkey, at the Istanbul Academy of Fine Arts. It is worth noting that almost all of them one way or another were involved in the cultural agenda of the newly formed Turkish Republic. For instance, Nikolai Kalmykoff and Rakhman Safiev among their other works at some point created portraits of Atatürk, one of the artworks presented at Roman Bilinski’s solo exhibition in 1934 was a bust of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, and it is reasonable to suppose that the costumes and decorations for the Akın theatre piece that was recommended to be staged personally by Atatürk were created by Nikolai Peroff. Last but not least, Crimean photographer Jules Kanzler who used to have a photo studio in Beyoğlu “documented” the early years of the Turkish Republic as well as the activities of its founders; the TBMM archive in Turkey contains an album of photographs taken by him during the celebrations of the tenth anniversary of the Republic’s foundation.

In lieu of conclusion

Engineer Vitaly Sorokin who moved from Petrograd to Constantinople in 1920 when he was only five years old, wrote the following about the rule of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (1923-1938) in of his letters: “He favored Russian refugees, never oppressed us, and with him we lived like in Jesus pocket”. There is every reason to believe this because the lives of the above-mentioned artists prove that those who wanted to work in Istanbul in the 1930s had the opportunity to work. In addition, the artists were free to practice their religions. Names were also changed by only a few of them, Nikolai Kalmykoff (became Naci Kalmukoğlu), Rahman Safiev (became Ibrahim Safi) and Jules Kanzler (became Izzet Kaya Kanzler). With the outbreak of World War II, the situation changed. At the time the Turkish authorities were pretty wary of Russian-speaking émigrés despite the fact that they were those Russians who twenty years ago had fled from the Bolsheviks. Thus, the artist and former member of the Union of Russian Painters in Constantinople, Nikolai Saraphanoff, and even some of his apprentices were imprisoned for many years in connection with the accusation of espionage for the Soviet state. According to the émigré Roxana Umarova (with whom Marina Sığırcı had a chance to speak personally), it happened shortly before the start of World War II, and the artist was falsely accused. Alas, we don’t know if there were other artists from the former Russian Empire with a similar tragic fate since the details of the life stories of many of the Russian-speaking artists in Istanbul are still unknown.

Ekaterina Aygün currently pursues her doctoral research project that deals with Russian-speaking artists in Istanbul at the beginning of the 20th century. Research interests include late Ottoman history, Turkish-Russian relations, urban history, art history and the history of women and gender. She is part of the Metromod research team and contributed a digital walk through the Russian speaking emigré’s Istanbul after 1918.