When the Struma dropped anchor in the Romanian port of Constanța on Friday 12 December 1942, the German Wehrmacht had conquered almost all of Europe. Leningrad in the north had been occupied since the end of 1941, and around a million people died, from hunger, cold and in German air attacks on the city. While in November 1942 Allied troops under US General Dwight D. Eisenhower opened a new front on the Moroccan and Algerian coasts (Operation Torch) to relieve their Soviet allies, the Holocaust had already begun. The first victims were over a hundred thousand handicapped people who had been murdered in gas chambers since September 1939. While 33,711 Jewish people died in a hail of bullets from special commandos, the SS and the Wehrmacht in Babyn Jar near Kiev in September 1941, the lethal effect of Zyklon B was tested on 900 prisoners of war of the Red Army in Auschwitz. Shortly before, the deportations of Jews, Roma and Sinti from Germany and Austria to concentration and extermination camps had begun.

The passengers on the Struma were mostly Romanian Jews who no longer saw any chance of survival on the European continent. Since September 1941, when racist laws had already made Jewish life in Romania unbearable, advertisements with the title “Vasul Struma” had been doing the rounds in Bucharest. The owner was Baruch Konfino, a Jewish ophthalmologist based in Varna and working for various Zionist organisations, who had already sent two decrepit ships with a total of 368 passengers on board to Palestine in 1939. Nearly 800 tickets were sold for passage on the ship, which had been launched in 1880 at the Palmers Shipbuilding & Iron Co. Ltd. shipyard in Newcastle upon Tyne, England, under the name Cornelia and originally had a capacity of one hundred to one hundred and fifty passengers. They had to pay two hundred thousand Lei for the crossing. They were told that they would receive their visas for Palestine in Istanbul. First they went by train from Bucharest to Constanța. There, the passengers were forced to undress and – except for wedding rings – hand over all valuables. They were not allowed to take more than twenty kilos of luggage. Just forty minutes after setting sail, the engines failed and the ship drifted in the open sea until the early hours of 13 December. The mechanic who finally repaired the engines left the Struma with two hundred and fifty wedding rings in his pocket.

The floating ghetto of Istanbul

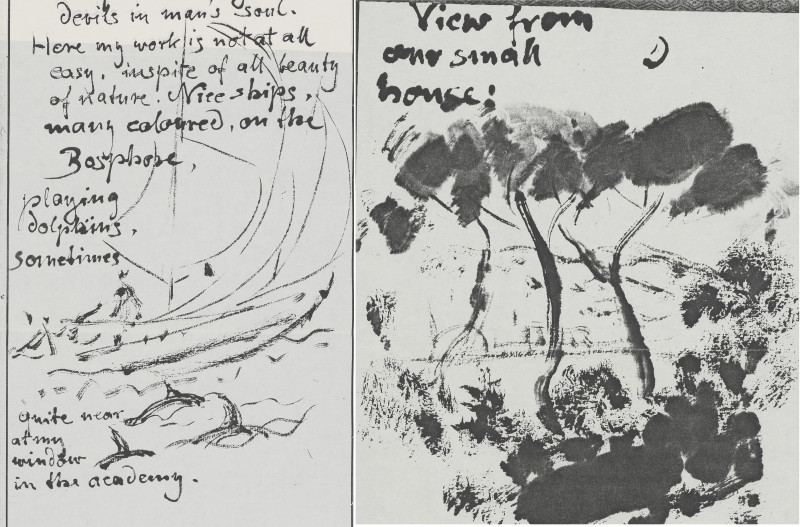

The ship reached Istanbul on 15 December 1942, but was not allowed to dock in the harbour and was towed to Sarayburnu when its engines failed again. On board were 103 children, 269 women and 406 men. Now began the endless wait, the nightmare for the passengers. The ship of hope that was supposed to take them safely to Palestine became a floating ghetto for the people on board. It was besieged by Turkish gunboats and quarantined with yellow flags. It was strictly forbidden to leave or approach the ship. The supply situation and the hygienic conditions on the already overcrowded yacht worsened from day to day. There was a lack of everything, especially food, and the first cases of dysentery soon appeared. Only two 16-year-old youths, Jakop Mandel and David Lazarescu, succeeded in getting off the boat unnoticed one evening at dusk. However, they were soon found and fished out of the icy waters of the Bosphorus. Before they were taken back on board, however, they were given something to eat, soup and chops. In return, the one was shirtless and the other one without belt, for those the two were given two postcards and a pen. Shortly before, the deportations of Jews, Roma and Sinti from Germany and Austria to concentration and extermination camps had begun.

The passengers on the Struma were mostly Romanian Jews who no longer saw any chance of survival on the European continent. Since September 1941, when racist laws had already made Jewish life in Romania unbearable, advertisements with the title “Vasul Struma” had been doing the rounds in Bucharest. The owner was Baruch Konfino, a Jewish ophthalmologist based in Varna and working for various Zionist organisations, who had already sent hundreds of Jewish two decrepit ships with a total of 368 passengers on board to Palestine in 1939. Nearly 800 tickets were sold for passage on the ship, which had been launched in 1880 at the Palmers Shipbuilding & Iron Co. Ltd. shipyard in Newcastle upon Tyne, England, under the name Cornelia and originally had a capacity of one hundred to one hundred and fifty passengers. They had to pay two hundred thousand leibs for the crossing. They were told that they would receive their visas for Palestine in Istanbul. First they went by train from Bucharest to Constanța. There, the passengers were forced to undress and – except for wedding rings – hand over all valuables. They were not allowed to take more than twenty kilos of luggage. Just forty minutes after setting sail, the engines failed and the ship drifted in the open sea until the early hours of 13 December. The mechanic who finally repaired the engines left the Struma with two hundred and fifty wedding rings in his pocket.

The ship reached Istanbul on 15 December 1942, but was not allowed to dock in the harbour and was towed to Sarayburnu when its engines failed again. On board were 103 children, 269 women and 406 men. Now began the endless wait, the nightmare for the passengers. The ship of hope that was supposed to take them safely to Palestine became a floating ghetto for the people on board. It was besieged by Turkish gunboats and quarantined with yellow flags. It was strictly forbidden to leave or approach the ship. The supply situation and the hygienic conditions on the already overcrowded yacht worsened from day to day. There was a lack of everything, especially food, and the first cases of dysentery soon appeared. Only two 16-year-old youths, Jakop Mandel and David Lazarescu, succeeded in getting off the boat unnoticed one evening at dusk. However, they were soon found and fished out of the icy waters of the Bosphorus. Before they were taken back on board, however, they were given something to eat, soup and chops. In return, the one was shirtless and the other one without belt, for those the two were given two postcards and a pen. They were never to know that the postcards would actually reach their mothers.

However, the fate of the refugees on the Struma did not go unnoticed. Numerous fighters from Zionist organisations flocked to Istanbul to come to the aid of the passengers. Among them was the Viennese Teddy Kollek, later mayor of Jerusalem. On the tenth day, the Polish immigrant Simon Brod, one of the representatives of the Istanbul Jewish community, received permission to bring food and medicine on board. “Don’t lose hope, be patient,” Brod comforted the passengers. News was now making the rounds that restored some hope. The United American Jewish Distribution Committee had donated ten thousand dollars to the Chief Rabbinate, and a yacht named “Lilly-Ayala” had been bought with it. Negotiations were underway with Spain, Argentina and Portugal, and if a neutral state would agree to the Lilly-Ayala sailing under their flag, they could travel on the day after tomorrow.

The Wannsee Protocol

On 20 January 1942, the 38th day that the Struma was stuck near Sarayburnu, leading Nazi officials agreed on the “Final Solution of the Jewish Question” at a conference at Wannsee. The conference minutes, which went down in history as the “Wannsee Minutes”, stated that “every effort would be made” to exterminate 11 million Jews in various countries in Europe. The sixth page of the report, written down by Adolf Eichmann, who was tried and executed in Jerusalem in 1962, and found among the files of the State Department in 1947, was a statistic of the Jewish population in Europe according to the countries in which they lived, even the 200 Jews living in Albania were not forgotten, nor were the 55,500 Jews in the European part of Turkey. They were all included in the extermination plan.

On the Struma, despair increased with each day of waiting. The Turkish authorities did not allow the ship to be towed on the sledge to the Kasımpaşa shipyard to repair the engine damage and let the waiting passengers ashore. The Turkish Prime Minister explained his government’s inaction with excuses like: “What should we do with a nation that other nations, especially the Germans, don’t want?” The appeals for help written on bed sheets by the passengers of the Struma, “S.O.S.”, “Save us!” were ineffective, as was the slogan “Long live the Republic of Turkey! Save us!”. The situation was not only determined by the rejectionist attitude of the Turkish authorities, but also by the refusal of the British colonial administration in Palestine to accept the refugees. The passengers were caught in a vicious circle, no one wanted to take them in and give them protection. So they were stranded in front of the Bosporus.

Only very few of the passengers who had braved cold, hunger, dysentery and despair for 71 days off the coast of Sarayburnu were able to leave the ship: the Romanian general manager of the Standard Oil Company of New York Martin Segall and his wife and child at the intercession of the influential entrepreneur Vehbi Koç. Theodor Benjamin Brettschneider, Emanuel Ghefner, David Israel, Tiwia Franck, Emanuel and Eduard Ludovic, who had a visa for Palestine, and Medea Salamovitz, because she was heavily pregnant. Medea Salamovitz was admitted to the Or Ahayim hospital in Balat. Her fiancé was not given permission to disembark. Meanwhile, the Turkish government also did not accept Britain’s concession that people under the age of 14 would be allowed to enter Palestine.

The Soviet submarine SC 213

On 23 February 1942, a Turkish tug approached the Struma. Around noon, two policemen came on deck. One explained that the ship was being disinfected and he told the captain to collect iron. “They’ll take you to the Black Sea,” the other policeman whispered to someone. At first the passengers were quiet, then some of them raised their voices, and finally there was a full-scale riot. Amid the shouts of protest, the two policemen left the Struma. Not long after, they returned with eighty uniformed men, armed and equipped with sticks. It was hopeless to resist them. After their resistance was broken, the Struma was pulled towards the Black Sea without anchor, rudder or engine.

It was a quiet night. No one spoke, the children did not cry. After the tugboat, which had released the moorings from the bow, left, the ship was targeted at dawn by the Soviet submarine SC 213 under the command of Captain Dimitri Mihaelovitch Dantjko.

The only surviving passenger David Stoliar never forgot the explosion. He did not forget that on 24 February 1942 the captain had shouted “torpedo”, the passenger named Grigori Buchspan had shouted “mine”, the children, the women, the men, the orange crates, the violin, the accordion and the smell of burnt milk powder. He did not forget that the Struma turned into a ball of fire and sank immediately, the children who fell into the cold water drowned immediately, he and Captain Lazar held on to the door of the floating bridge and beat each other so as not to freeze and not to sleep. He also did not forget that Captain Lazar was submerged in the water towards morning, that he tried to commit suicide with a pocket knife, and that he could not slit his wrists because his fingers were frozen.

From the direction of Şile, he finally saw a fishing boat. The fishermen rescued him and took care of him for two days before calling the police. The police picked up David Stoliar and he was first taken to Şile, then to Üsküdar police department, then to Haydarpaşa hospital, then to police headquarters. He was interrogated for three weeks. With criminal record number 704, he was photographed. The police chief explained that the lifeboats could not have come to the rescue because of the thunderstorm at sea. Davit Stoliar replied, “But the water was dark, lonely and calm”. The police chief ran his mouth: “I know what I’m saying, shut your mouth!” Simon Brod, who rescued him from the police, said, “To have survived the Struma is already a miracle, an even greater miracle it is to survive as the only eyewitness to this disaster in the hands of the police.”

Efforts to absolve Turkey of any responsibility in the affair

This affair is one of the most shameful chapters in Turkey’s history. The only comprehensive study on Struma in Turkey was recorded by Professor Çetin Yetkin. But it is an extremely superficial analysis and ignores the simplest principles of scientific research. It is particularly significant that Yetkin does not know the identity of Maria Arsena, especially since he cites her as the main source. Maria Arsena, the Romanian writer, is actually Arthur Leibovici, whom Çetin Yetkin writes about in detail in the chapter “Passengers”. If Yetkin had taken a look at the list of passengers, he would have discovered the names of Basa and Salomon Leibovici, who lost their lives on the Struma, and would have understood Arthur Leibovici’s interest in the Struma, namely his kinship with the two victims. Arthur Leibovici wrote his works under the pseudonym of his wife Maria Arsena.

Ethical values such as comparing sources, dealing with details and treating the victims with respect lose meaning when propaganda and the acquittal of Turkish politics become the main goal of the investigation instead of investigating and analysing the affair accurately and impartially. In the end, Yetkin was even led to the anti-Semitic stereotype of accusing survivor David Stoliar of working for British intelligence and bombing the ship himself.

In fact, the Struma tragedy is also used to spread anti-Semitic narratives: “It is questionable that only one person from this ship survived. That can’t be consistent with ‘principles of sea rescue’. Perhaps there are more Jews who were rescued from other ships? The experts say it is possible. These Jews could be hidden in Turkey after all. It is said that these Jews did business in Turkey with the gold and jewellery they had with them, forming partnerships with the famous businessmen of the time.”

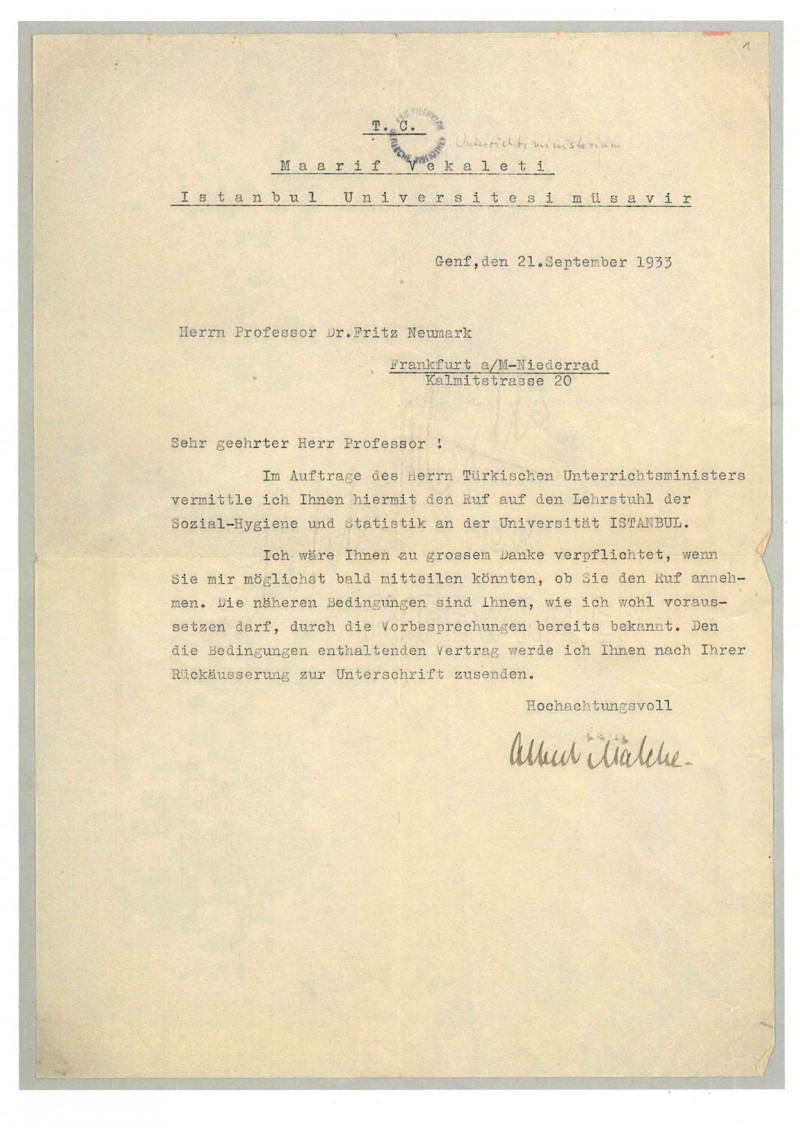

Struma is one of those events where humanity perished. The ignorance towards a group that was annihilated persecuted and murdered by the Nazis, the ignorance and hatred towards refugees, affected almost every country. Although Turkey was a neutral country during the Second World War and did not want to take its responsibility in this affair, just as in other events, it is always pointed out that Turkey took in Jews at that time, like the German and Jewish intellectuals who found refuge in Turkey during the Nazi period. However, this is contrasted with the pogroms in Eastern Thrace in the summer of 1934 against the Jewish minority, during which an estimated ten thousand Jews were expelled, and the “Turks speak Turkish” campaigns, or the Varlık Vergisi enacted in 1942, when the genocide reached its peak, the fact that Turkey did not protect its own citizens living in Europe during the Second World War, so that more than 3,000 of its citizens died in Nazi concentration camps. And it is undesirable to remember that 80 per cent of the Jewish people left Turkey after the Second World War.