“Sugihara asked his government to provide these [transit visa]. Without them, it would not be possible to get away from the Russians. Sugihara apparently knew the fate that threatened Jews in Poland and everywhere in Europe. He first asked his government for permission for these visas to be granted by Japan. The government refused. They didn’t want to be burdened with us. It was then that he gave us the permits, as we had another goal. We wouldn’t remain in Japan.”

Marcel Weyland (Interview with POLIN, 2015)

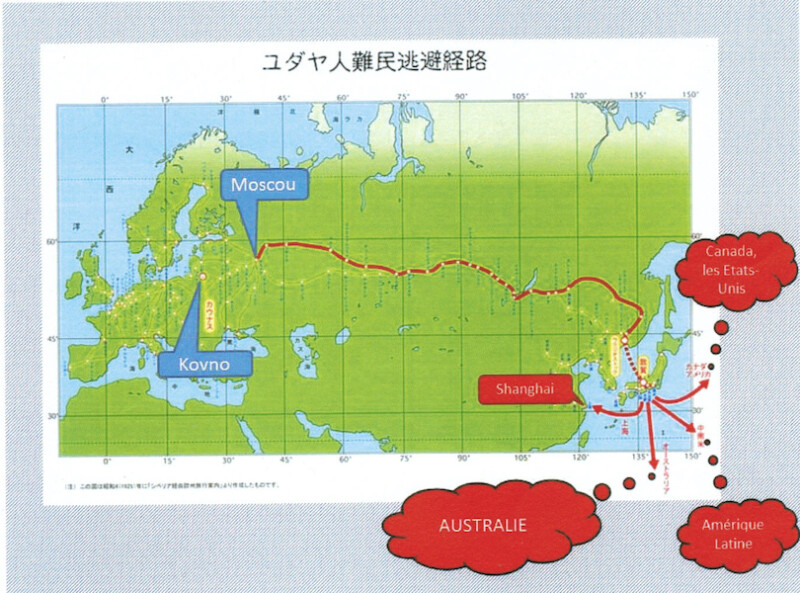

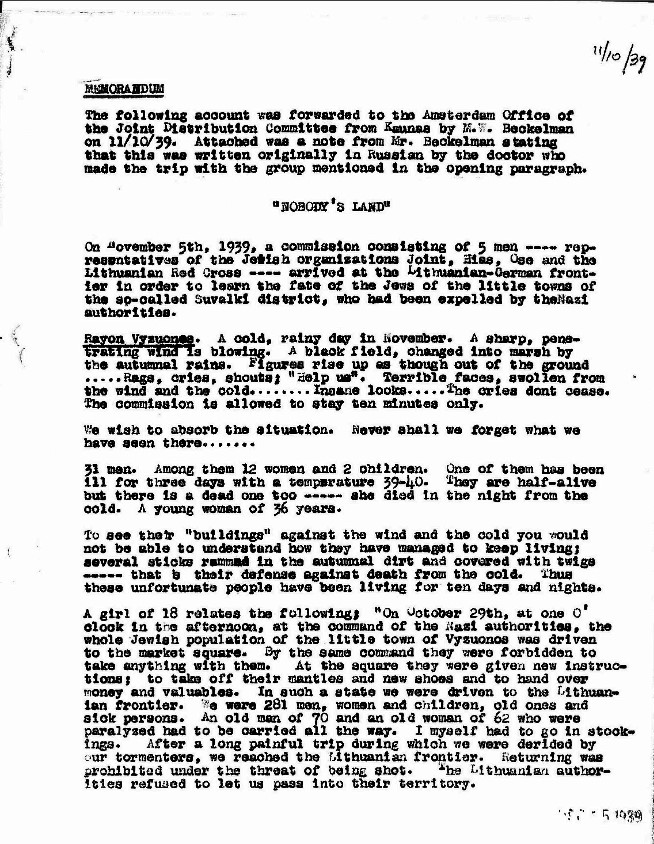

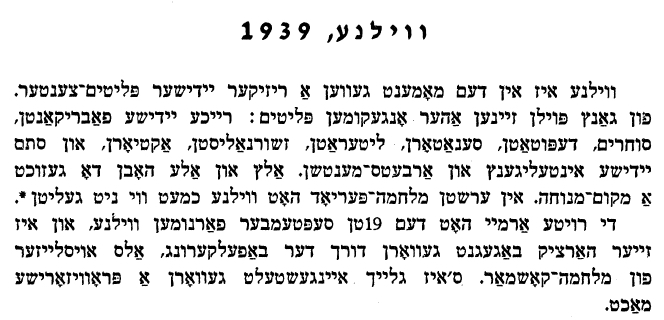

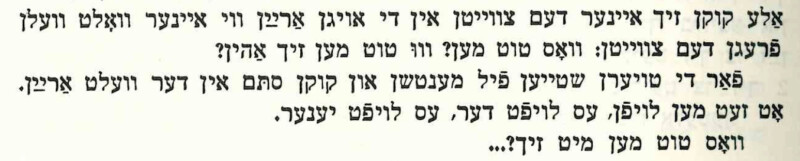

The members of the Weyland family were among several thousand Polish citizens, Jewish and non-Jewish, who escaped to Vilnius in the wake of the German invasion starting on September 1, 1940. Like the majority of refugees, they saw Vilnius as a temporary haven and transit for continued flight out of Europe. Both the threat of a Soviet and the anxiety of a German occupation of neutral Lithuania were incentives to organize a continued flight.

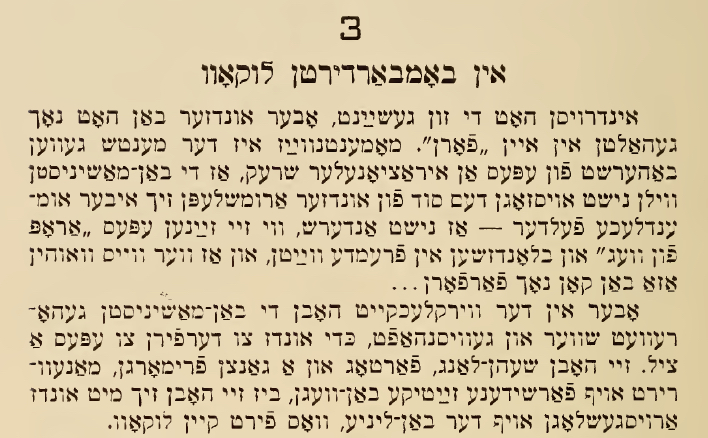

In the spring of 1940, a group of Polish refugees, most of them of Jewish origin and among them the Weylands, approached Sugihara Chiune (1900–1986), serving as the vice consul of the Empire of Japan in Kaunas. While the Weylands left Vilnius already in April 1940, most refugees were more anxious than ever to escape from the Baltic region after the Soviet annexation of Lithuania in the summer of 1940.

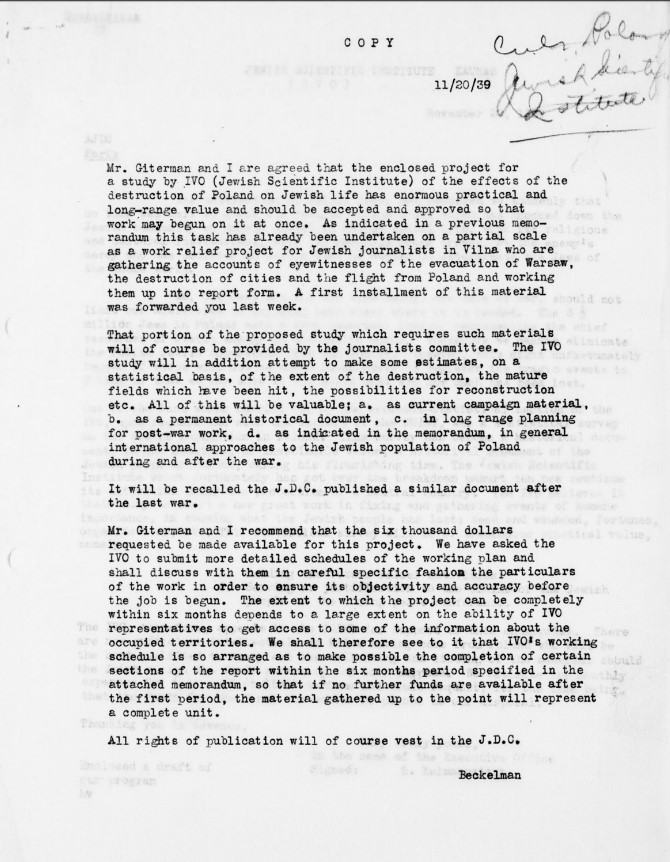

Some of them first approached the Dutch consul in Kaunas, Jan Zwartendijk, who provided them with visas to Curaçao in the Caribbeans. In order to reach Curaçao via the Soviet Union and Japan, they needed transit visas, however – and Sugihara was the one who provided them. As the rumors about this opportunity spread, many more refugees came to the tiny Japanese consulate in Vaizganto Street. Sugihara asked Yosuke Matsuoka, Minister of Foreign Affairs, to issue Japanese transit visas to Jewish refugees in July 1940. In its many replies, the Foreign Ministry advised Sugihara not to infringe upon the general rule regarding transit visas by the Japanese government which required that visas should

be issued only to those who had gone through appropriate immigration procedures and had enough funds for travel and accommodation. Despite these orders, Sugihara granted a few thousand visas (2,139 registered) that allowed their recipients, many of whom were children such as Marcel, to leave the region. Numbers are as usual much debated but, altogether, as many as six thousand refugees have been estimated who used them to escape the region.

Ten months later, shortly after Nazi Germany had attacked the Soviet Union, the vast majority of the Jewish community in Lithuania was gradually killed in the Holocaust. By then, the grantees of Sugihara’s transit visas had headed mainly to East Asia via the Trans-Siberian Railroad. Marcel Weyland remembers:

“I remember how we travelled through Moscow. They told us that the train would stop there and would stay they for several hours and that it would leave at five o’clock. […] We went off to see the cathedral and the Kremlin, and casually returned an hour before the planned departure. But there was no train – it had left. Fortunately, there was a taxi at the station and so we chased after the train in that taxi and caught it at the next station. Somehow, we managed to get back onto the train. Over the next three weeks, the train passed through Sverdlovsk, Tomsk, Novosibirsk, around the Baikal River to Birobidzhan”.

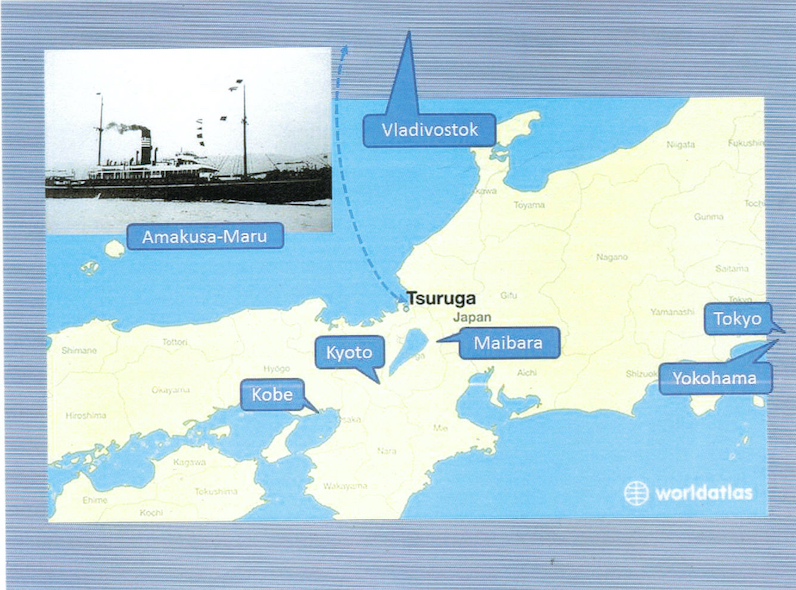

The Weyland family, like many others, reached Japan by boat. Legally, they were permitted to stay for ten days, but they ended up staying for seven months. The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee assisted to find accommodations. Once the Japanese government realized that the Weyland family were staying illegally, they were given a five-day-ultimatum to leave. With the help of Tadeusz Romer, the Polish Consul in Japan, they got to Shanghai where they lived in a camp for stateless persons and ultimately reached Australia.

Sugihara himself left Kaunas for different posts in Prague, Koenigsberg, and finally Bucharest between the Fall of 1941 and the Summer of 1944. While he did not risk his life to issue the transit visa, his activism did resist the general exclusive orders and saved many lives. When the Soviets occupied Romania, Sugihara and his family were arrested. After being held in an internment camp, he was able to return to Japan in 1947. After his return, he was dismissed or pressured to resign from the foreign (the details remain unclear). Only decades later, in 1985, he was recognized by Yad Vashem as a Righteous Among the Nations.

Sugihara’s rescue story is acclaimed in Japan since 1990s when his wife Yukiko published her memoir book on her husband’s life and his activities. His story was televised in December 1992, books and translations were published, films were made, a memorial park opened and a museum established.

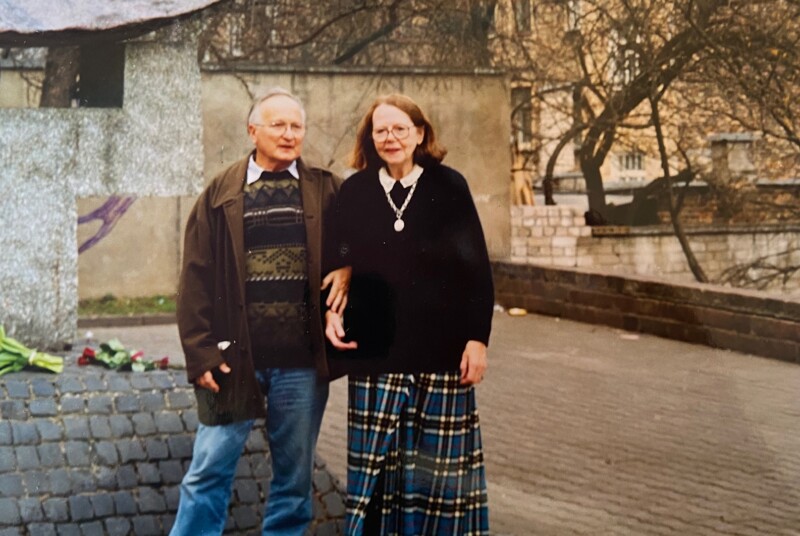

Sugihara also entered the Lithuanian memory culture. The most important site of memory is the modest building of the former Japanese consulate in Kaunas. In 1999 the building became the residence of the Sugihara Foundation ‘Diplomats for Life.’ A memorial museum was also established. Since 2001, the Sugihara House annually awards a prize entitled “The Person of Tolerance” to Lithuanian citizens and foreigners alike who work against manifestations of racism, xenophobia, and anti-Semitism in Lithuania. Marcel Weyland and his wife visited the monument in Vilnius on their trip to Lithuania in 2005.

Both the Lithuanian and Japanese memorial culture are interesting examples of the general “rescuer cult” that dominates many countries in an attempt to outshine the pervasive local collaboration in the Nazi genocide by stories of rescue of Jews in the case of Lithuania or to overwrite the outright alliance with the Nazi regime in the case of Japan. True, Sugihara’s actions did save a lot of lives and each additional life is to be celebrated. But do we have to wrap this story in narratives of heroism?

Courtesy of the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jewry | Stories of Refuge

The photographs were taken from Marcel Weyland’s private archives and were donated by the POLIN Museum.

Interview: Klara Jackl, Przemysław Jaczewski, POLIN Museum (2015)

Translation: Andrew Rajcher