I may also mention that the book was written during the war and at Istanbul, where the libraries are not well equipped for European studies. International communications were impeded; I had to dispense with almost all periodicals, with almost all the more recent investigations, and in some cases with reliable critical editions of my texts. Hence it is possible and even probable that I overlooked things which I ought to have considered and that I occasionally assert something which modern research has disproved or modified. I trust that these probable errors include non which effect the core of my argument. The lack of technical literature and periodicals may also serve to explain that my book has no notes. Aside from the texts, I quote comparatively little, and that little it was easy to include in the body of the book. On the other hand it is quite possible that the book owes its existence to just this lack of a rich and specialized library. If it had been possible for me to acquaint myself with all the work that has been done on so many subjects, I might never have reached the point of writing.

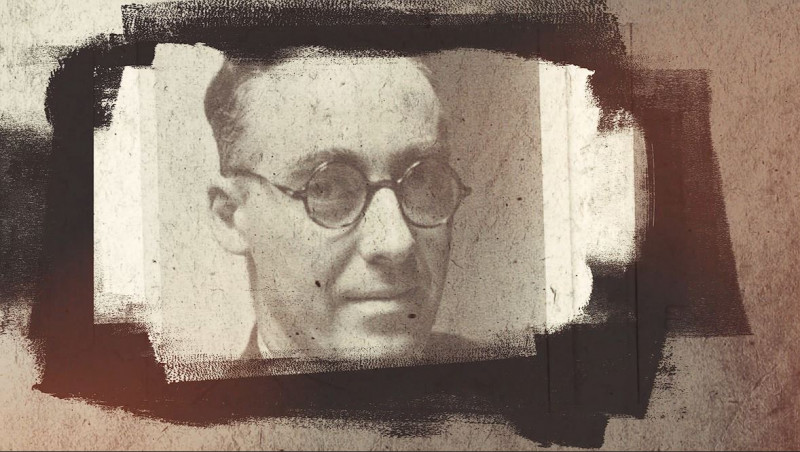

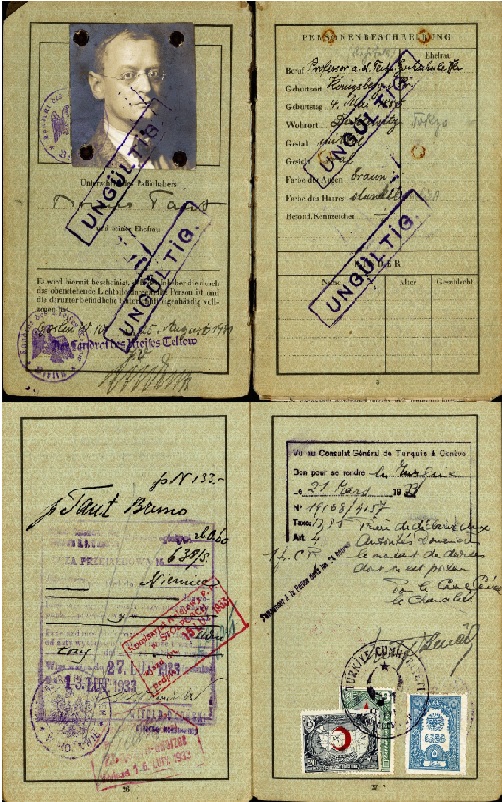

Erich Auerbach was a German Romance philologist, literary and cultural scholar. As for countless others, his career in Germany was ended prematurely due to the racist “Law on the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service,” ratified on April 7, 1933, which aimed at both the removal of Jewish civil servants and the dismissal of political “dissidents.” Since the so-called Frontkämpferprivileg (Privilege of Combatants) applied to him and he additionally even swore an “oath of loyalty of German civil servants” to Adolf Hitler in 1934, he lost his chair of Romance philology at the University of Marburg “only” at the end of 1935. More than foreseeable, however, he contacted colleagues in Italy, England, and other places already in the course of 1935 in order to find a suitable position, even far below the rank of professor. Thanks to the interdenominational and anti-racist self-help organization “Notgemeinschaft deutscher Wissenschaftler im Ausland,” founded in 1933 which from 1933 onward focused on emigration to Turkey, he finally followed the call to the İstanbul Üniversitesi. The latter had been founded in 1933 as part of the Kemalist program of Westernization and modernization, and one of its tasks was to recruit experts. In this way, several hundred German intellectuals and their families emigrated to Turkey, especially to the urban centers of Istanbul and Ankara, where they became involved in the work of the universities and ministries. Since Auerbach’s hopes of returning to a chair at a German university remained unfulfilled, he emigrated from Turkey to the United States in 1947, where he continued his academic career.

He is still one of the most important representatives of his field today. His main work, written in Istanbul between 1942 and 1945, Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature is one of the fundamental works of German Romance studies. Footnote-less, a kind of myth surrounds the study today. It is also the product of a paradox: Auerbach desperately needed a specialized library in Istanbul; but completed Mimesis precisely because of the lack of it. In short, this monumental work was created thanks to the city on the Bosporus – not only, but especially, because Auerbach survived the Holocaust here. The fact that the scientific discipline of comparative literature, of all things, is said to have been founded by a refugee in the metropolis at the crossroads between Europe and Asia is both extremely significant and symbolic.

Erich Auerbach, Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature – New and Expanded Edition (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013), 557.