The Arrival of Hannah Arendt

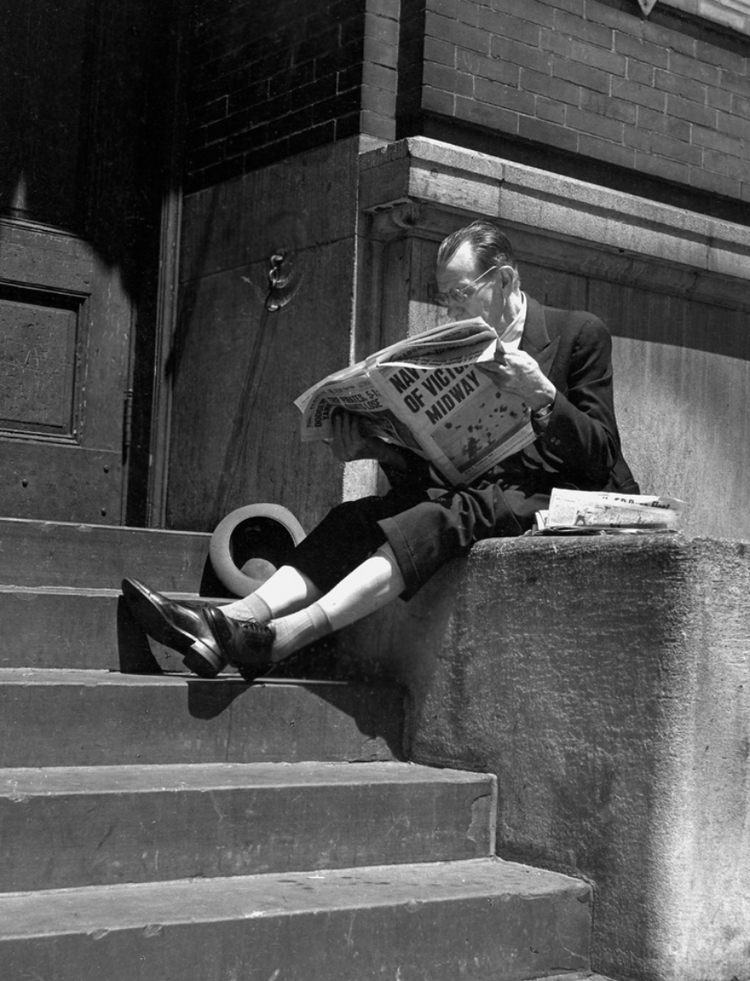

This film describes the arrival of Hannah Arendt - a Jewish, German-American political theorist and publicist - in New York and her reflections on flight and helping people start over.

Welche Eindrücke aus der ersten Woche in New York sind unvergesslich geblieben?

Dies schreckliche Wohnen während der ersten Nacht in einem Gemeindehaus. Sechs Frauen schliefen in einem Zimmer. Aber eine Handtasche durfte man dort nicht stehen lassen. Am nächsten Tag bin ich zu Dr. Edelheim gegangen, den ich von der CV-Zeitung 11“Central Verein-Zeitung. Blätter für Deutschtum und Judentum. Organ des Central-Vereins deutscher Staatsbürger jüdischen Glaubens e.V. Allgemeine Zeitung des Judentums.” Die CV-Zeitung war eine der bedeutendsten jüdischen Wochenzeitungen im deutschen Sprachraum und erschien von 1922 bis zu ihrem Verbot 1938. kannte, und der hat mir ein Dienstmädchenzimmer bei einem bekannten Arzt verschafft, und da habe ich gewohnt, also gegen baby-sitting einmal die Woche. Daraus sind dann siebenmal die Woche geworden, aber ich habe das durchgehalten und habe mir dann selber Stellungen gesucht. Habe dann als Kindermädchen gearbeitet, habe danach Massage gelernt, machte dann aus einem Hobby einen Beruf, lehrte Gymnastik. Immerhin, das brachte genügend Geld, um auch meine Eltern zu ernähren, die 1941 nach New York kamen. Mein Vater erhielt später einen Job als elevator operator, Nachtschicht, da brauchte er kaum Englisch zu reden. Meine Mutter ist in die Häuser gegangen, hat gekocht, hat gebacken, bis ich gesagt habe: Ich erlaube das nicht mehr, da wirst du zu sehr ausgenutzt. Ja, in New York Fuß zu fassen, das war schon eine schwierige Sache.

[…]

Ich habe einen enormen Respekt vor allem vor den Frauen. Ich kenne viele, die hatten früher ihre Dienstmädchen, und dann wurden sie selber Dienstmädchen, und sie haben es mit Grazie gemacht, sie haben ihren Männern geholfen. Die Akademiker mussten noch einmal studieren, Zahnärzte, Anwälte usw. Die Frauen haben es geschafft, während des Studiums sich und die Männer zu ernähren und keine Gesichter zu schneiden. Das war ja gar nicht so einfach. Sie waren alle schon in vorgerückten Jahren, wie zum Beispiel meine Eltern, die sich nach einem Leben voll Arbeit zur Ruhe hätten setzen sollen. Da mussten sie von unten, so weit unten waren sie in ihrem Leben nie wieder anfangen, noch einmal Geld zu verdienen. Diese Lebensleistung verdient einfach Respekt.

Which impressions from the first week in New York remain unforgettable?

This terrible living during the first night in a community center. Six women slept in one room. But one was not allowed to leave a handbag there. The next day I went to Dr. Edelheim, whom I knew from the CV newspaper, 11“Central Verein-Zeitung. Blätter für Deutschtum und Judentum. Organ des Central-Vereins deutscher Staatsbürger jüdischen Glaubens e.V. Allgemeine Zeitung des Judentums.” The CV-newspaper was one of the most important Jewish weekly newspapers in the German-speaking world and appeared from 1922 until it was banned in 1938. and he got me a maid’s room with a well-known doctor, and that’s where I lived, in exchange for baby-sitting once a week. That turned into seven times a week, but I kept it up and then looked for positions myself. I then worked as a nanny, then learned massage, then turned a hobby into a profession, taught gymnastics. At least, that brought enough money to feed my parents, who came to New York in 1941. My father later got a job as an elevator operator, night shift, he hardly needed to speak English. My mother went to the houses, cooked, baked, until I said: I don’t allow that anymore, you’re being exploited too much. Yes, getting a foothold in New York was a difficult thing.

[…]

I have enormous respect for women in particular. I know many who used to have their maids, and then they became maids themselves, and they did it with grace, they helped their husbands. The academics had to study again, dentists, lawyers, etc. The women managed to feed themselves and their husbands while studying, and they didn’t cut faces. That was not so easy. They were all in advanced years, like my parents, for example, who should have retired after a lifetime of work. They had to start from the bottom, they had never been that far down in their lives, to earn money again. This life achievement simply deserves respect.

Hilde Marx (born November 1, 1911 in Bayreuth) was a German-American poet, writer and journalist. She is one of the authors whose writing career was only just beginning when the National Socialists came to power in Germany in 1933, and was immediately prevented by them. As a Jew, however, she was already affected by anti-Semitism before that. She already experienced what it meant to be Jewish at the Humanist Gymnasium. After graduating from high school in 1931, Hilde Marx began studying journalism, theater and art history in Berlin. After five semesters, however, she was forcibly de-registered, as Jews were no longer allowed to attend universities. While she was still able to publish for newspapers at “Ullstein,” “Mosse” and the “Berliner Tageblatt,” this was no longer possible after their “Aryanization. She was left only with Jewish publications, such as “Die Monatsblätter des jüdischen Kulturbundes in Deutschland,” “Die Jüdische Revue,” “Das Jüdische Gemeindeblatt,” and above all the “C.V.-Zeitung”. 11“Central Verein-Zeitung. Blätter für Deutschtum und Judentum. Organ des Central-Vereins deutscher Staatsbürger jüdischen Glaubens e.V. Allgemeine Zeitung des Judentums.” The CV-newspaper was one of the most important Jewish weekly newspapers in the German-speaking world and appeared from 1922 until it was banned in 1938.

She did not think about emigration for a long time, but when the Gestapo threatened her with imprisonment in a concentration camp in 1937, she fled to the Czech Republic, and from there she managed to leave for the USA a year later. In November 1938 she arrived in New York. She worked in various jobs: as a nurse for the elderly, a saleswoman, a nanny and a gymnastics trainer. However, in addition to these demanding jobs, she also tried to gain a foothold as a writer in the USA. To this end, she asked the American Guild for German Cultural Freedom for help.

In 1943 she received American citizenship. In America she continued to perform as a lecture artist, with her own “One woman show” in which she combined serious with light-hearted, Jewish with Christian traditions. In 1951, a final volume of poems from 1938 to 1951 was published under the title “Bericht,” which incorporated her experiences as an exile.

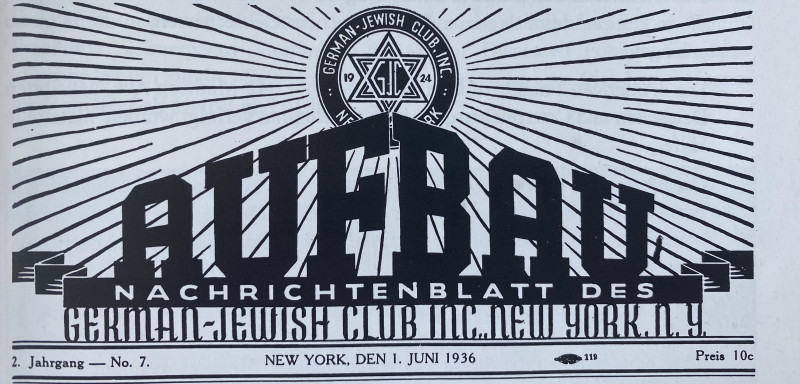

She became a member of Auslands-PEN and, from the 1960s on, was an editor of “Aufbau”, 22“Aufbau”: In 1934, the first “Aufbau. Nachrichtenblatt des German-Jewish Club, Inc., New York” appeared. Initially more a club and advertising organ, the “Aufbau” soon became a news sheet about the everyday life of German (not only Jewish) emigrants in exile. This meant advice on legal matters, explanations of the New York subway system, language courses and job vacancies, tips on dealing with authorities, etc. Oskar Maria Graf and Nelly Sachs, Lion Feuchtwanger and Thomas Mann, Mascha Kaléko and many others wrote here. for which she wrote primarily theater and film reviews, as well as short biographies of Jewish emigrants. She also worked for other newspapers, such as “This Day from St. Louis,” “The Chicago Jewish Forum,” the state newspaper and “Herold from New York”.

Henri Jacob. Hempel (Hrsg.),1983: Wenn ich schon ein Fremder sein muß… Deutsch-jüdische Emigranten in New York. Frankfurt/M.-Berlin-Wien: Ullstein Verlag, pp. 51-52, 58.

Translation from German to English © Minor Kontor / We Refugees Archive.