The Arrival of Hannah Arendt

This film describes the arrival of Hannah Arendt - a Jewish, German-American political theorist and publicist - in New York and her reflections on flight and helping people start over.

Wie haben Sie es geschafft, Ihre Eltern aus dem von Hitler’s Wehrmacht bereits besetzten Europa herauszuholen?

Wissen Sie, die meisten von uns kamen mit einer langen Namensliste von Freunden, Bekannten, manchmal Verwandten, denen wir Affidavits verschaffen wollten. Wir wollten zugleich New York erobern an einem Tag oder auch Amerika, wir wollten das alles gestern abschicken. Und dann wurden wir ernüchtert, haben gesehen, wie wahnsinnig schwer das ist. Dass die Leute entweder nicht helfen konnten oder nicht helfen wollten, also ich habe die ersten drei Wochen damit verbracht, nach Affidavit-Gebern zu suchen. Es war sehr schwierig, denn essen musste man ja irgendwie. Für meinen Lebensunterhalt hatte ich selbst zu sorgen.

Dann traf ich einen Geschäftsfreund meines alten Herrn aus Chicago. Der hat mir ein lunch spendiert, doch blieb er mir ein hundertprozent fremder Mensch. Er fragte mich: Haben Sie noch jemanden drüben? Ja, sagte ich, meine Eltern. Warum sind sie denn nicht hier? fragte er bohrend. Da habe ich geantwortet: Hören Sie mal, ich bin selbst eine kurze Zeit hier, und ich brauchte noch zwei Affidavits. Die werde ich Ihnen geben, sagte er fast ungeduldig. Solche Zufälle gab es auch. Dagegen bin ich zu den Verwandten meiner Mutter gegangen, die denselben Namen hatten, den meine Mutter als Mädchen hatte. Irrsinnig reiche Leute in der Park Avenue. Die haben mir Tee servieren lassen und Kekse, und als ich dann sagte, was ich wollte, haben sie abgewehrt. Unser Anwalt hat gesagt, wir dürfen nichts mehr unterschreiben. Aber komm doch wieder einmal zum Tee. Das war das erste und das letzte Mal, dass ich sie gesehen habe. Ich meine, das ist die menschliche Natur.

Ihre Eltern haben Europa zu einem Zeitpunkt verlassen, als Hitlers Judenverfolgung zur Judenvernichtung wurde. Haben Ihre Eltern darüber berichtet?

Meine Eltern mussten pro Person 960 Dollar für die Überfahrt bezahlen. Die Schiffscompanien waren damals richtige Seeräuber, wir waren ihnen ausgeliefert. Mein Mann, ich habe erst 1943 geheiratet, der eine Riesenfamilie hatte, der hat Jahre um Jahre an den Schulden abgezahlt, die er damals gemacht hat, um die Schiffskarten an seine Verwandten zu schicken, die sie dann alle nicht mehr ausnutzen konnten. Sie waren inzwischen abtransportiert worden. Aber auf den Schulden blieb er sitzen. Das ist genau, wie wenn jemand einen halbtoten Menschen auf der Strasse ausraubt, ungefähr dieselbe Mentalität. Grauenhaft. Aber man hat doch alles getan, und ich habe das grosse Glück gehabt, meine Eltern noch rüberzubringen. Drei Wochen hat ihre Reise gedauert, von Lissabon über die Kanarischen Inseln; drei Wochen haben sie in einem Laderaum gehaust, unvorstellbare Zustände, es gab nur wenig zu essen, in erschreckendem Zustand kamen sie hier an. Ich hatte ein Kellerzimmer gemietet, und ich weiss noch, wie meine Mutter, die an eine herrliche Zehn-Zimmer-Wohnung gewöhnt war, früher in Bayreuth, gefragt hat: Dort sollen wir wohnen? Sie haben sich auch daran gewöhnt, denn sie hatten in der Zwischenzeit ja Schlimmeres erfahren.

How did you manage to get your parents out of Europe, which was already occupied by Hitler’s Wehrmacht?

You know, most of us came with a long list of names of friends, acquaintances, sometimes relatives, to whom we wanted to get affidavits. At the same time, we wanted to conquer New York in one day, or even America, we wanted to send it all off yesterday. And then we became disillusioned, saw how insanely difficult it is. That people either couldn’t help or didn’t want to help, so I spent the first three weeks looking for affidavit givers. It was very difficult, because you had to eat somehow. I had to provide for my own living.

Then I met a business friend of my old man from Chicago. He bought me lunch, but he remained a hundred percent stranger to me. He asked me: Do you have anyone else over there? Yes, I said, my parents. Why aren’t they here? he asked piercingly. That’s when I replied: Listen, I am here for a short time myself, and I needed two more affidavits. I will give them to you, he said almost impatiently. There were such coincidences, too. In contrast, I went to my mother’s relatives, who had the same name my mother had as a girl. Insanely rich people on Park Avenue. They had tea served to me and cookies, and then when I said what I wanted, they brushed it off. Our lawyer said we can’t sign anything else. But do come again for tea. That was the first and last time I saw them. I mean, that’s human nature.

Your parents left Europe at a time when Hitler’s persecution of the Jews became the extermination of the Jews. Did your parents tell about this?

My parents had to pay 960 Dollars per person for the crossing. The ship companies were real pirates at that time, we were at their mercy. My husband, I got married in 1943, who had a huge family, spent years and years paying off the debts he incurred at the time to send the ship tickets to his relatives, all of whom were then unable to take advantage of them. They had been taken away in the meantime. But he was left with the debt. That’s just like someone robbing a half-dead person on the street, about the same mentality. Horrible. But everything was done, and I was very lucky to get my parents across. Their journey took three weeks, from Lisbon via the Canary Islands; they lived in a hold for three weeks, unimaginable conditions, there was little to eat, they arrived here in a frightening condition. I had rented a basement room, and I still remember how my mother, who was accustomed to a magnificent ten-room apartment, formerly in Bayreuth, asked: Is that where we should live? They got used to it, too, because they had experienced worse things in the meantime.

Hilde Marx (born November 1, 1911 in Bayreuth) was a German-American poet, writer and journalist. She is one of the authors whose writing career was only just beginning when the National Socialists came to power in Germany in 1933, and was immediately prevented by them. As a Jew, however, she was already affected by anti-Semitism before that. She already experienced what it meant to be Jewish at the Humanist Gymnasium. After graduating from high school in 1931, Hilde Marx began studying journalism, theater and art history in Berlin. After five semesters, however, she was forcibly de-registered, as Jews were no longer allowed to attend universities. While she was still able to publish for newspapers at “Ullstein,” “Mosse” and the “Berliner Tageblatt,” this was no longer possible after their “Aryanization. She was left only with Jewish publications, such as “Die Monatsblätter des jüdischen Kulturbundes in Deutschland,” “Die Jüdische Revue,” “Das Jüdische Gemeindeblatt,” and above all the “C.V.-Zeitung”. 11“Central Verein-Zeitung. Blätter für Deutschtum und Judentum. Organ des Central-Vereins deutscher Staatsbürger jüdischen Glaubens e.V. Allgemeine Zeitung des Judentums.” The CV-newspaper was one of the most important Jewish weekly newspapers in the German-speaking world and appeared from 1922 until it was banned in 1938.

She did not think about emigration for a long time, but when the Gestapo threatened her with imprisonment in a concentration camp in 1937, she fled to the Czech Republic, and from there she managed to leave for the USA a year later. In November 1938 she arrived in New York. She worked in various jobs: as a nurse for the elderly, a saleswoman, a nanny and a gymnastics trainer. However, in addition to these demanding jobs, she also tried to gain a foothold as a writer in the USA. To this end, she asked the American Guild for German Cultural Freedom for help.

She did not think about emigration for a long time, but when the Gestapo threatened her with imprisonment in a concentration camp in 1937, she fled to the Czech Republic, and from there she managed to leave for the USA a year later. In November 1938 she arrived in New York. She worked in various jobs: as a nurse for the elderly, a saleswoman, and a nanny. In 1943 she received American citizenship. In America she continued to perform as a lecture artist, with her own “One woman show” in which she combined serious with light-hearted, Jewish with Christian traditions.

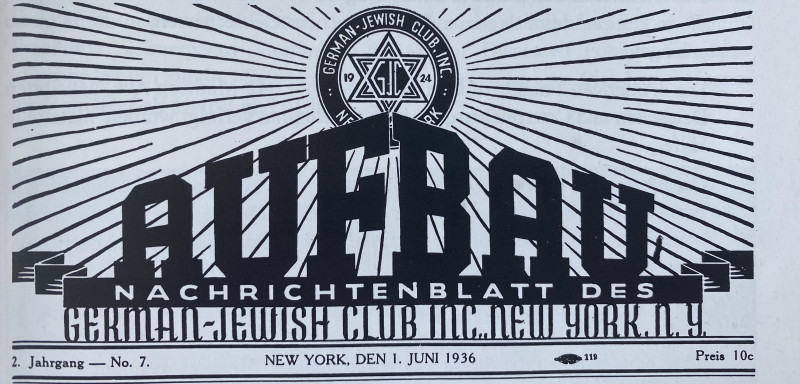

In 1951, a final volume of poems from 1938 to 1951 was published under the title “Bericht,” which incorporated her experiences as an exile. She became a member of Auslands-PEN and, from the 1960s on, was an editor of “Aufbau”, 22“Aufbau”: In 1934, the first “Aufbau. Nachrichtenblatt des German-Jewish Club, Inc., New York” appeared. Initially more a club and advertising organ, the “Aufbau” soon became a news sheet about the everyday life of German (not only Jewish) emigrants in exile. This meant advice on legal matters, explanations of the New York subway system, language courses and job vacancies, tips on dealing with authorities, etc. Oskar Maria Graf and Nelly Sachs, Lion Feuchtwanger and Thomas Mann, Mascha Kaléko and many others wrote here. for which she wrote primarily theater and film reviews, as well as short biographies of Jewish emigrants. She also worked for other newspapers, such as “This Day from St. Louis,” “The Chicago Jewish Forum,” the state newspaper and “Herold from New York”.

Henri Jacob. Hempel (Hrsg.),1983: Wenn ich schon ein Fremder sein muß… Deutsch-jüdische Emigranten in New York. Frankfurt/M.-Berlin-Wien: Ullstein Verlag, p. 51-52, 54, 57.

Translation from German to English © Minor Kontor / We Refugees Archive.