The Arrival of Hannah Arendt

This film describes the arrival of Hannah Arendt - a Jewish, German-American political theorist and publicist - in New York and her reflections on flight and helping people start over.

Betrachten Sie Ihre Emigration als einen einschneidenden Bruch in Ihrem Leben?

Nur Bruch. Dass ich und sehr viele andere, dass wir uns quasi an unserem Schopf wieder raufgezogen haben, ist eine Sache. Das ist ein so glatter Bruch, dass es direkt fremd auf mich wirkt. Für viele Leute ist die Emigration nicht so glatt gegangen. Ich behaupte heute noch, dass ein jeder von uns, ich nehme mich nicht aus, etwas weg hat. Ein Trauma, das bei manchen so schlimm ist, dass sie irgendwo im Sanatorium landen, oder schlimmer: im Selbstmord. Bei anderen ist es kaum merkbar da, aber es ist da, es ist unbedingt da. Schauen Sie mal, ich muss zum Beispiel sehr oft zurückhalten und mit mir selber sprechen, wenn ich mit meinen Kindern spreche, und sie beklagen sich über dieses und jenes, um nicht zu sagen: Denkt mal dran, was mit mir war, wie ich in eurem Alter war. Weil das nämlich keinen Sinn hat, weil das nur antagonisiert, ich beherrsche mich bewusst. Aber man kann sagen, es ist immer da, immer gegenwärtig, ob das im Träumen ist, im Wachen ist, es ist immer da. Das allein ist natürlich für einen Menschen eine grosse Belastung.

Sie haben mal gesagt: Eigentlich geht es den Emigranten gut hier. Da kann ich nur Brecht anführen: Die einen gehen im Lichte, und man sieht nur die im Lichte sind, die im Dunkeln sieht man nicht. Es sind sehr viele im Dunkeln, und die sieht man nicht. Die Sozialfürsorge drüben war immer viel besser. Wir haben hier einige Fortschritte gemacht, aber mit den alten Leuten ist es wirklich schlimm, auch wenn sie nicht völlig mittellos sind. Da kommen die Erinnerungen, und Sie wissen, je älter man wird, desto weiter geht man in der Erinnerung zurück, während man vergisst, was gestern war. Und dann leiden sie noch einmal die ganze Sache durch. Das ist etwas Fürchterliches.

[…]

Der Begriff „Heimat“ existiert für mich nicht mehr. Den gab es mal sehr stark, aber der ist mir ausgetrieben worden durch äusserst radikale Mittel. Das kommt dem Begriff „Heimat“ nahe, und doch ist damit etwas gänzlich gemeint.

[…]

Ich meine, was heisst hier Wiedergutmachung? Was kann man um Gottes willen wiedergutmachen? Man kann mit Geld Dinge erleichtern. Gewöhnlich läuft es darauf hinaus, dass Geld für Krankheiten gezahlt wird und für Zustände, die durch die Verfolgungszeit bedingt sind. Man kann mit Geld ein bisschen helfen, die Sache etwas zu erleichtern, aber gutmachen? Der verkehrteste Ausdruck, den ich kenne.

Einen Zusammenhang zwischen finanziellen Leistungen und moralischer Wiedergutmachung zu konstruieren, ist sicherlich untauglich, wenngleich von einigen Politikern in der Bundesrepublik bewusst gewählt, und damit zu suggerieren, dass es keiner weiteren Aufarbeitung deutscher Vergangenheit bedarf.

Ich erinnere mich noch, als mein Mann an diese Frage kam, da hat er gesagt: Ich will nichts. Da habe ich gesagt: Ja, warum nicht? Er hat sich einfach gewehrt, er hat gesagt: Weil ich nicht ausrechnen kann, wie viele Tage meine Mutter im Konzentrationslager war, und dann bekomme ich soundsoviel für jeden Tag, den sie dort gelitten hat. Ich kann das nicht. Und mein Mann ist nicht der einzige, der so denkt. Ich kenne andere Leute, die das einfach nicht mit ihrem Gewissen, mit ihrem Gefühl verbinden können. Ich lass mich nicht bezahlen für das Leiden meiner Kinder, meiner Geschwister, meiner Eltern. Das muss man auch verstehen. Es ist zwar dumm, aber verständlich.

Do you consider your emigration to be a decisive break in your life?

Only break. That I and very many others, that we have pulled ourselves back up by our hair, as it were, is one thing. It’s such a smooth break that it seems directly foreign to me. For many people, emigration didn’t go so smoothly. I still maintain today that each of us, I do not exclude myself, has taken away some damage. A trauma that for some is so bad that they end up in a sanatorium somewhere, or worse: suicide. For others, it’s barely noticeable, but it’s there, it’s absolutely there. Look, for example, I very often have to hold back and talk to myself when I talk to my children, and they complain about this and that, not to say: think about what was with me when I was your age. Because that has no sense, because that only antagonizes, I control myself consciously. But you can say it is always there, always present, whether it is in dreaming, in waking, it is always there. That alone, of course, is a great burden for a person.

You once said: Actually, the emigrants are doing well here. I can only quote Brecht on that: Some walk in the light, and you only see those who are in the light; you don’t see those in the dark. There are very many in the dark, and you don’t see them. Social welfare over there has always been much better. We’ve made some progress here, but it’s really bad with the old people, even if they’re not totally destitute. That’s where the memories come in, and you know the older you get, the further you go back in your memory as you forget what yesterday was. And then they suffer through the whole thing again. That’s a terrible thing.

[…]

The term “home” no longer exists for me. It once existed very strongly, but it has been driven out of me by extremely radical means. That comes close to the concept of “home”, and yet something entirely is meant by it.

[…]

I mean, what does “Wiedergutmachung” 11Reparation payments to survivors of the Holocaust, literally “to make good again” or to compensate. mean here? What can you make good again for God’s sake? You can make things easier with money. Usually it boils down to paying money for illnesses and for conditions caused by the persecution period. You can help make things a little easier with money, but make good? The most backwards expression I know.

Constructing a connection between financial benefits and moral reparations is certainly unsuitable, although deliberately chosen by some politicians in the Federal Republic, and thus suggesting that there is no need for further reappraisal of Germany’s past.

I still remember when my husband came to this question, he said: I don’t want anything. Then I said: Yes, why not? He simply resisted, he said: Because I can’t calculate how many days my mother was in the concentration camp, and then I get so-and-so much for every day she suffered there. I can’t. And my husband is not the only one who thinks that way. I know other people who just can’t connect that with their conscience, with their feeling. I don’t let myself pay for the suffering of my children, my siblings, my parents. You have to understand that, too. It’s stupid, but it’s understandable.

Hilde Marx (born November 1, 1911 in Bayreuth) was a German-American poet, writer and journalist. She is one of the authors whose writing career was only just beginning when the National Socialists came to power in Germany in 1933, and was immediately prevented by them. As a Jew, however, she was already affected by anti-Semitism before that. She already experienced what it meant to be Jewish at the Humanist Gymnasium. After graduating from high school in 1931, Hilde Marx began studying journalism, theater and art history in Berlin. After five semesters, however, she was forcibly de-registered, as Jews were no longer allowed to attend universities. While she was still able to publish for newspapers at “Ullstein,” “Mosse” and the “Berliner Tageblatt,” this was no longer possible after their “Aryanization. She was left only with Jewish publications, such as “Die Monatsblätter des jüdischen Kulturbundes in Deutschland,” “Die Jüdische Revue,” “Das Jüdische Gemeindeblatt,” and above all the “C.V.-Zeitung”. 11“Central Verein-Zeitung. Blätter für Deutschtum und Judentum. Organ des Central-Vereins deutscher Staatsbürger jüdischen Glaubens e.V. Allgemeine Zeitung des Judentums.” The CV-newspaper was one of the most important Jewish weekly newspapers in the German-speaking world and appeared from 1922 until it was banned in 1938.

She did not think about emigration for a long time, but when the Gestapo threatened her with imprisonment in a concentration camp in 1937, she fled to the Czech Republic, and from there she managed to leave for the USA a year later. In November 1938 she arrived in New York. She worked in various jobs: as a nurse for the elderly, a saleswoman, a nanny and a gymnastics trainer. However, in addition to these demanding jobs, she also tried to gain a foothold as a writer in the USA. To this end, she asked the American Guild for German Cultural Freedom American Guild for German Cultural Freedom for help.

In 1943 she received American citizenship. In America she continued to perform as a lecture artist, with her own “One woman show” in which she combined serious with light-hearted, Jewish with Christian traditions.

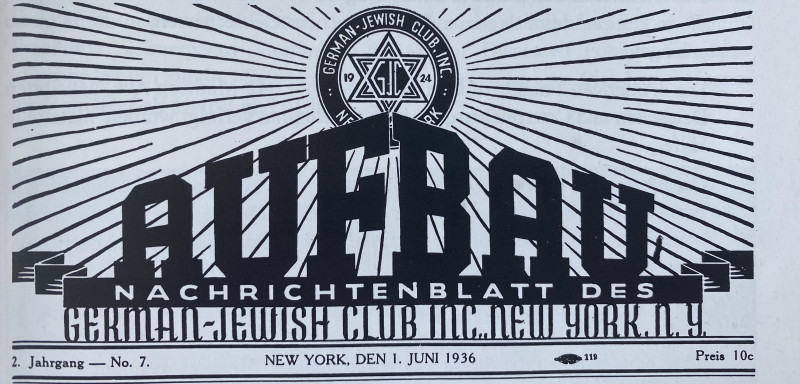

In 1951, a final volume of poems from 1938 to 1951 was published under the title “Bericht,” which incorporated her experiences as an exile. She became a member of Auslands-PEN and, from the 1960s on, was an editor of “Aufbau”, 22“Aufbau”: In 1934, the first “Aufbau. Nachrichtenblatt des German-Jewish Club, Inc., New York” appeared. Initially more a club and advertising organ, the “Aufbau” soon became a news sheet about the everyday life of German (not only Jewish) emigrants in exile. This meant advice on legal matters, explanations of the New York subway system, language courses and job vacancies, tips on dealing with authorities, etc. Oskar Maria Graf and Nelly Sachs, Lion Feuchtwanger and Thomas Mann, Mascha Kaléko and many others wrote here. for which she wrote primarily theater and film reviews, as well as short biographies of Jewish emigrants. She also worked for other newspapers, such as “This Day from St. Louis,” “The Chicago Jewish Forum,” the state newspaper and “Herold from New York”.

Henri Jacob. Hempel (Hrsg.),1983: Wenn ich schon ein Fremder sein muß… Deutsch-jüdische Emigranten in New York. Frankfurt/M.-Berlin-Wien: Ullstein Verlag, pp. 62-63, 67, 69.

Translation from German to English © Minor Kontor / We Refugees Archive.