Excerpts from the interview „Edith Hillinger: Building a Life, San Francisco, June 2006“, conducted by Richard Whittaker

Richard Whittaker: Well, I didn’t quite know where to start. Edith is one of those artists for whom making art is a real search, one that has persisted for years and years. But there’s also the quite interesting story about your life. Having been born in Germany, your family had to flee the Nazis when you were still quite young. And you ended up in Turkey living in Istanbul, where you spent most of your childhood until you moved to New York at sixteen or so. So I thought maybe we could start there with your family being uprooted and then living in Turkey. Could you tell us a little about that?

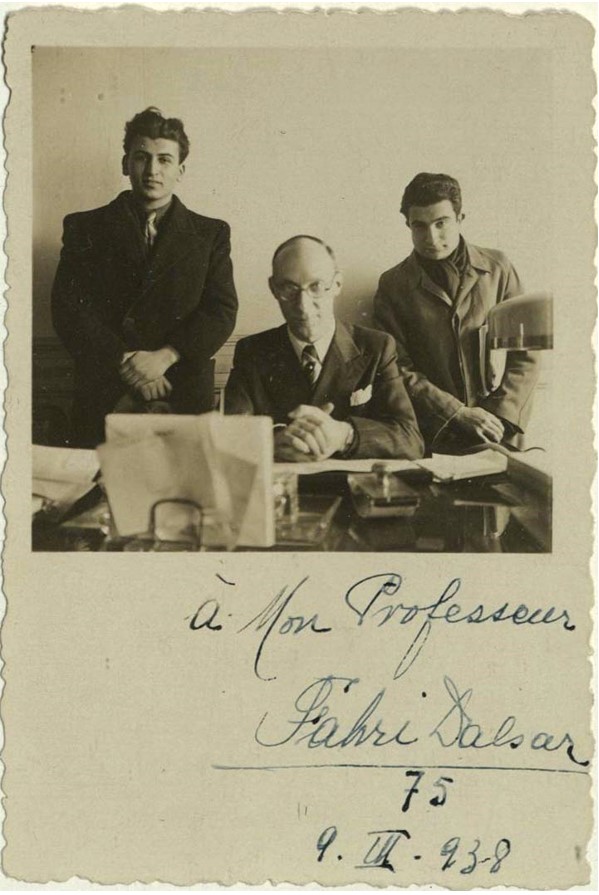

Edith Hillinger: Our family was caught up in the turmoil that millions and millions of people were caught up in, which is the beginnings of the second World War, and the displacement of people from many countries. But really, it all goes back so much further. This is the interesting thing about history and the threads of history. If you start pulling at the threads, you start going back further and further. One of the reasons we wound up in Turkey was because Atatürk, the founder of modern Turkey, had connections to Germany early on in the 1920s, so already you’re back in an earlier time. He invited scientists and architects, like my father, to come to Turkey to help him found a modern university to train young Turks in all kinds of disciplines. And the fact that my father was in Germany also goes back to the 1920s. He was a Hungarian Jew born in 1895. When he came back from the First World War, he wanted to attend the university in Budapest to study architecture, but just at that time they had had an uprising, which was blamed on a Jew, and the universities were suddenly closed to all Jews. That propelled him to Germany, to Berlin to study architecture. So that was the beginning of our family history, because my father looked for a room to rent and knocked on a door. That was where my mother lived. Her parents were renting out rooms to students. They were German Protestants. So that’s how everything is so intertwined, both in the personal history and in the larger domains of national histories.

My parents had a lot of difficulty getting out of Germany. My mother was not Jewish, but she understood, as my father did, that if they stayed they would both be killed. They didn’t have any illusions about that. They understood that perfectly, since my father had already fled once. They tried to go to different countries, but you couldn’t really leave Germany unless you had some kind of invitation to go someplace. You couldn’t just cross the border. They wouldn’t allow that.

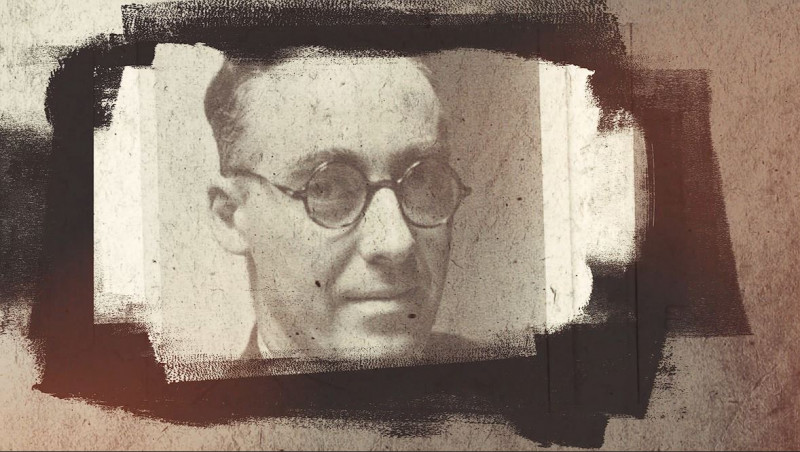

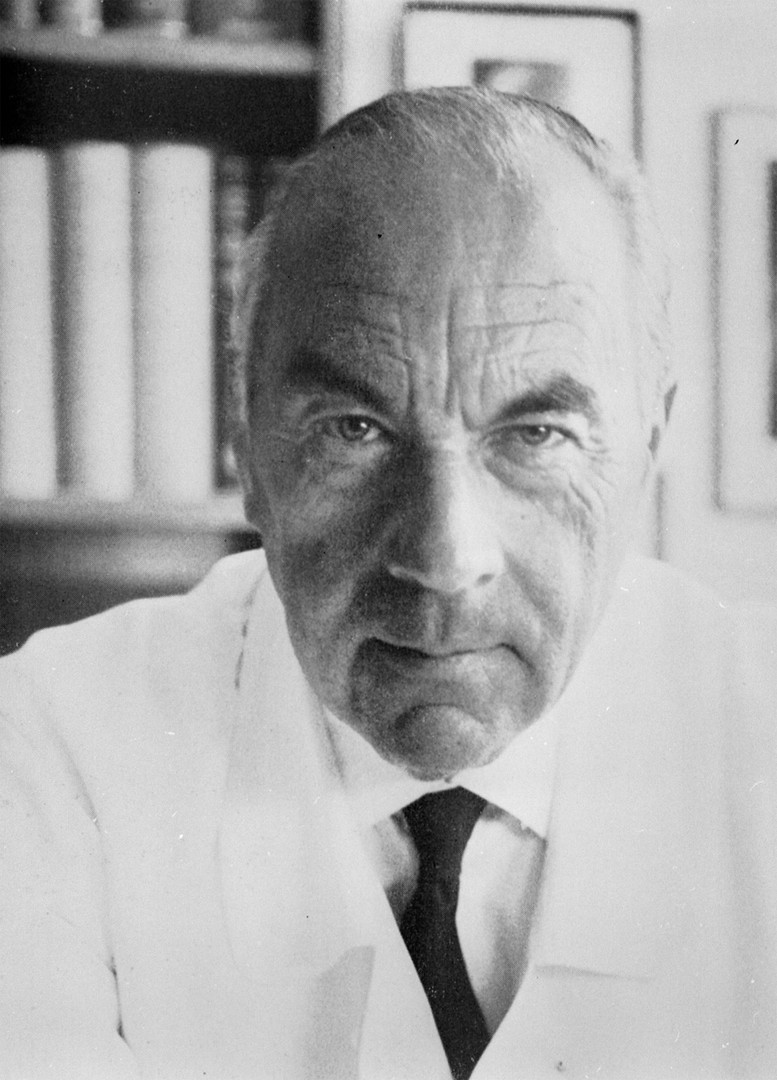

So my father’s mentor was Bruno Taut, who was a German architect, not Jewish. He fled Nazi Germany because he was a Communist, a well-known Communist, and the Nazis hated the Communists as well. Bruno Taut was on a world tour at that time. First he went to Russia. Since he was a Communist, he thought that would be Nirvana, but when you get to Russia it’s a little different from being a Communist at a distance. [laughs] So that didn’t sit well with him. Then he ended up in Japan, and he was enormously interested in Japanese architecture.

In his time, Bruno Taut was really well known as one of the founders of modern architecture. Anyway, then he went to Turkey, where he didn’t live very long. But when he heard of my father’s plight—they had worked together in Germany—he convinced the government in Turkey to send for my father. My mother saved all the documents, which are very interesting. I put them into the archives at the Academy in Berlin this past year. I still had the telegram from Bruno Taut to my father saying, “Come right away!” There was a job offer from Turkey. That’s what saved our lives, basically.

We went on the Orient Express. I haven’t been able to find out where we boarded the train, because I don’t think it went to Berlin. Anyway my father went three months ahead of us to get settled and then we left. My mother’s family stayed behind because they were not Jewish, and they actually survived the war.

From the time I was three and a half to when I was almost sixteen we lived in Turkey. Then we sailed for the United States on a very small freighter in the midst of October storms. My mother was a phenomenally healthy woman until she was in her nineties, but everybody on the boat was seasick, all seven passengers, including the captain. I remember my mother taking care of everybody.

Edith Hillinger, born in Berlin in 1933, fled with her parents from Nazi Germany to Istanbul in 1937. Her father Franz Hillinger had already fled from Hungary to Germany after the First World War, after being barred from studying there as a Jew. In Turkey he worked together with his mentor Bruno Taut, who had already come there in 1936 and who was given important positions to reform Turkish architecture. In view of the few opportunities to escape, Edith Hillinger describes the job offer as a lifesaver.

When she was 16 years old, Edith moved on to New York City with her mother. Since then she has lived and worked in the USA as an artist. Her art is also influenced by the impressions of her childhood and youth in Istanbul. In this interview passage, she talks about the circumstances of her family’s flight to Turkey in 1937.

Excerpts from an interview conducted by Richard Whittaker on June 24, 2006, originally published in Works & Conversations.

We thank Edith Hillinger for kindly allowing us to use the excerpts from her website: https://edithhillinger.com/interview