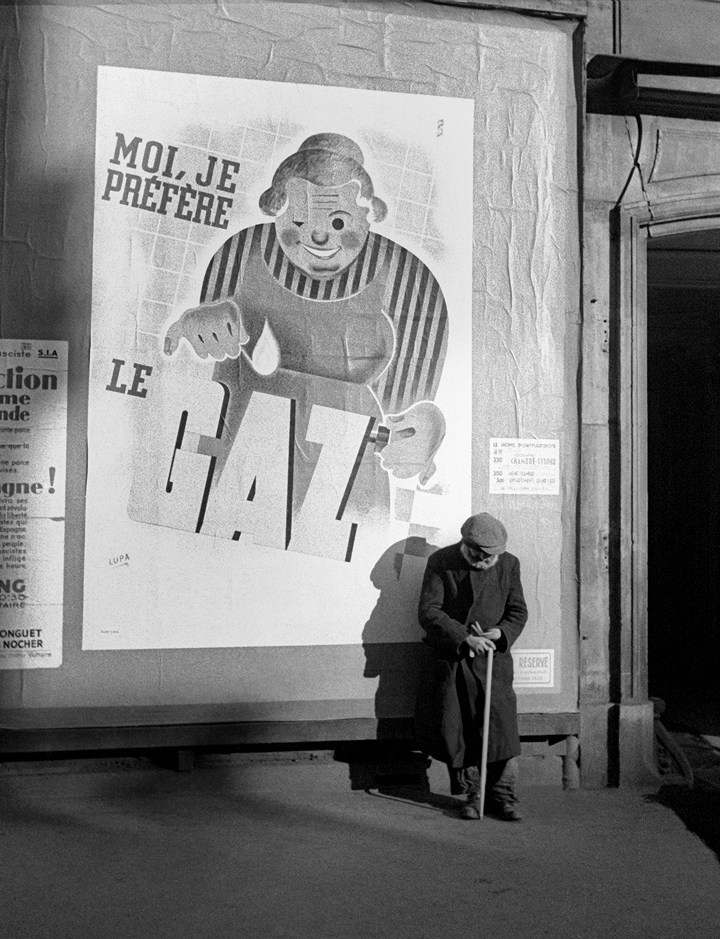

A few weeks after our arrival in the camp … France was defeated and all communications broke down. In the resulting chaos we succeeded in getting hold of liberation papers with which we were able to leave the camp. There existed no French underground at the time (the French resistance movement sprang up much later, namely when the Germans decided to draft Frenchmen for forced labor in Germany whereupon many young people went into hiding and then formed the maquis). None of us could “describe” what lay in store for those who remained behind. All that we could do was to tell them what we expected would happen – the camp would be handed over to the victorious Germans. (About 200 women of a total 7,000 left.) This happened, indeed, but since the camp lay in what later became Vichy-France, it happened years later than we expected. The delay did not help the inmates. After a few days of chaos, everything became very regular again and escape was almost impossible. We rightly predicted this return to normalcy. It was a unique chance, but it meant that one had to leave with nothing but a toothbrush since there existed no means of transportation.

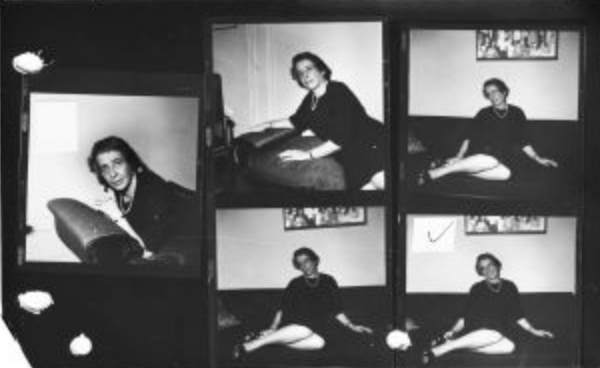

Hannah Arendt (1906-1975) was a Jewish German-American political theorist and writer.

After being detained by the Gestapo for several days in 1933, she fled to France and worked there, among other things, in Zionist organizations that helped Jews to escape. In 1937 she was deprived of German citizenship, which made her a stateless person for almost 14 years. After she was imprisoned for a few weeks in the French internment camp Gurs, she managed to escape from there as well. In this excerpt, she describes the exact circumstances of the escape from Gurs and how important it was to take advantage of the extremely limited opportunities to escape in an anticipatory manner.

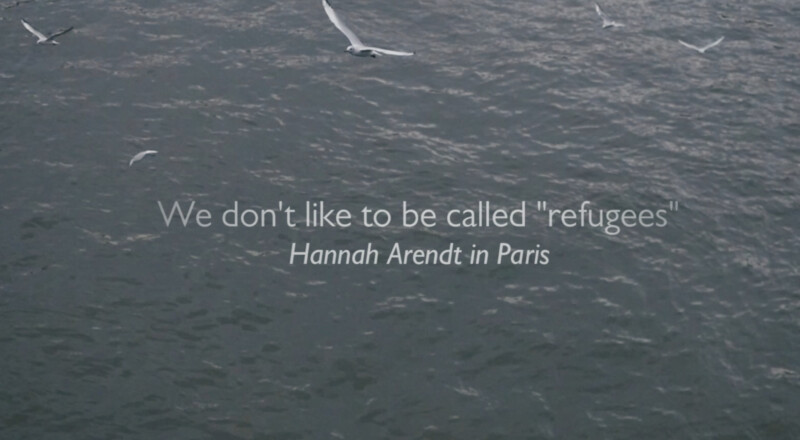

In 1941 Arendt came to the USA, where she spent the rest of her life and was granted US citizenship in 1951. In her first years in New York she worked as a publicist, editor and contributor to several Jewish magazines (including “Der Aufbau”) and organizations (including the Commission on Jewish Cultural Reconstruction). Under the impression of the experience of flight and arrival that she and other European Jews had had, she also wrote the essay “We Refugees” in the Menorah Journal in 1943. From 1953 to 1967 Arendt taught as a professor at Brooklyn College in New York, at the University of Chicago and at the New School for Social Research in New York.

Excerpt from a letter to Midstream magazine, 1962.

Cited in: Young-Bruehl, Elisabeth, 1982: Hannah Arendt. For Love of the World, New Haven and London. P. 155.