7 September 1939

The highway we are traveling on is even more crowded with refugees than yesterday. Everyone is running, rushing as if he were pursued. Everyone gives the impression that he knows he is too late. We learn that at dawn today on the radio all men were ordered to leave Warsaw. Now the nervousness of our wives when we spoke with them by telephone earlier today becomes clear.

People who left Warsaw today tell horrible stories. The fields around the capital are flooded with people: thousands of pedestrians – Jews and Christians, men and women, old and young, a sea of limousines, military cars.

At about 9 in the morning we had the first air raid, and it lasted all day without letup. That day was extremely hard. Dozens of times we ran from the carts to hide from the bombers. Horrible scenes took place in the forest. People look for family members who got lost in the dark of night. Women and children shudder. Men, tired from running, throw off their shoes and run barefoot. Horses are frightened by the bombing and run away with the wagons, leaving the passengers in the forest.

Everyone trembles with fear. As soon as we hear explosions, people cling to each other. People can’t lie still and simply run off aimlessly. People chase after one another. In some cases people lose their senses and run away from the crowd, thinking this will save them. People run after them and bring them back. Everybody’s eyes blaze. The ground shakes. The forests rise up. The rattling of machine guns is jolting, and the fear keeps rising. The road from Otwock to Garwolin was then a horrible hell.

12 September 1939

It is still dawn. We go into the woods toward the village of Luty.

In the village, we have encountered several wagons full of people who, like us, have come here to hide.

Everyone one of the newcomers has taken pains to “get hold of” a better hut, a few trees where you should be able to hide, or something like that.

On one of the village huts we noticed a Jewish name. We go in – they really are Jews!

We spent three days in that village, with that Jewish family. We arrived there a day before Rosh Hashanah and left after the holiday was over.

A few days after the German invasion of Poland, Herman Kruk (1897-1944), a Polish Jew and activist of the Bund, decides to leave Warsaw facing the immanent danger in face of the approaching Wehrmacht. In his diary, he describes the chaos of his and other people’s flight. Furthermore, he reports about his stay in a village called Luty where he celebrates Rosh HaShana, the Jewish New Year, together with other refugees at the home of a Jewish family from the village.

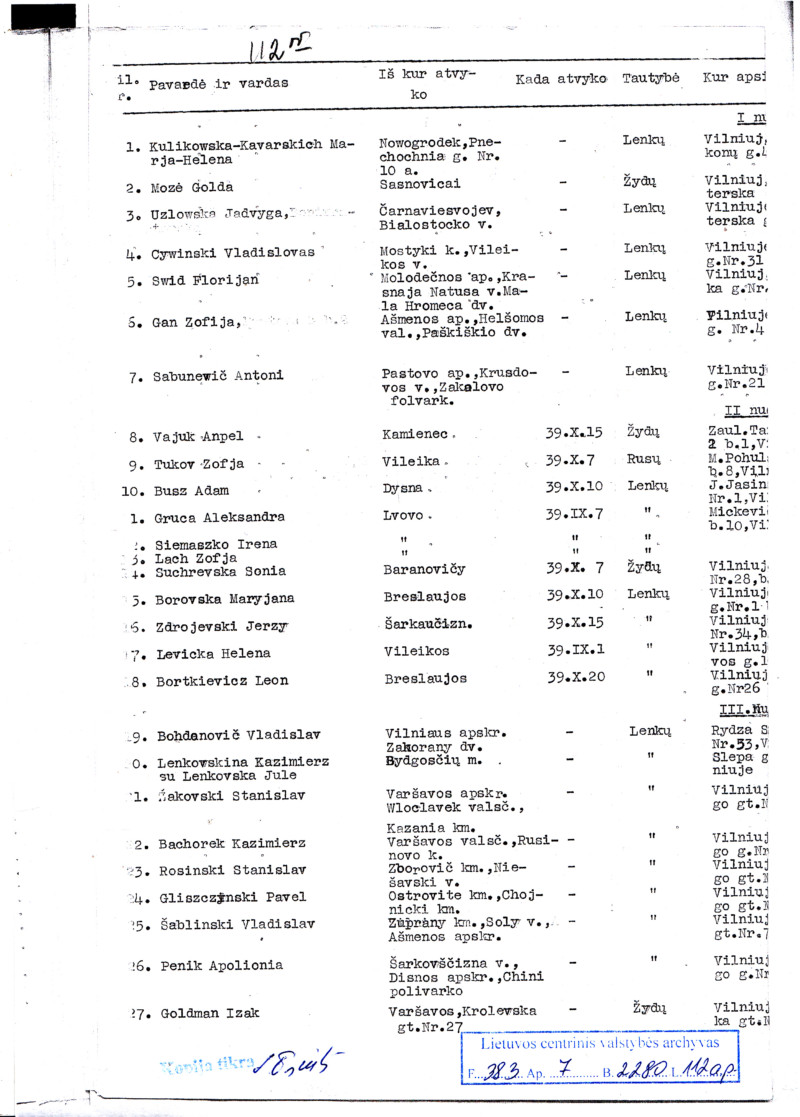

Other reports about the chaotic flight from occupied Poland to Vilnius were given by Pese R., Chaim-Leyb D. and others in interviews with the “Committee to Collect Material about the Destruction of Polish Jewry, 1939“. Their reports from the basis of the We Refugees Archive films “Fleeing through Poland” and “No Man’s Land“.

Kruk fled to Vilnius and lived there for almost four years. He experienced the fate of the Jewish community under Soviet, Lithuanian, again Soviet and finally German occupation. From 1941 until 1943, he lived in the Vilna Ghetto. Kruk documented his time in Vilnius as a chronicler, describing the support networks for Jewish-Polish refugees in the city before its occupation, his attempts to leave the city and his despair about the invasion of the German Wehrmacht, his grief about the fate of his home city Warsaw and his decision to write down his experiences for future generations. In 1943, he was deported to the concentration camp Klooga near Tallinn where he was murdered in September 1944 right before the Red Army liberated the camp. Parts of his manuscripts are still missing.

Kruk, Herman, 2002: The Last Days of the Jerusalem of Lithuania. Chronicles from the Vilna Ghetto and the Camps, 1939-1944, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, pp. 3-4, 11.