The Arrival of Hannah Arendt

This film describes the arrival of Hannah Arendt - a Jewish, German-American political theorist and publicist - in New York and her reflections on flight and helping people start over.

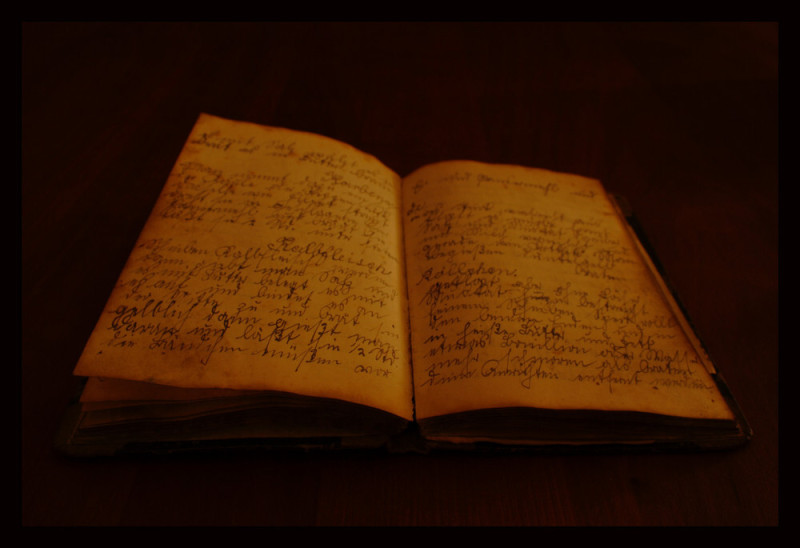

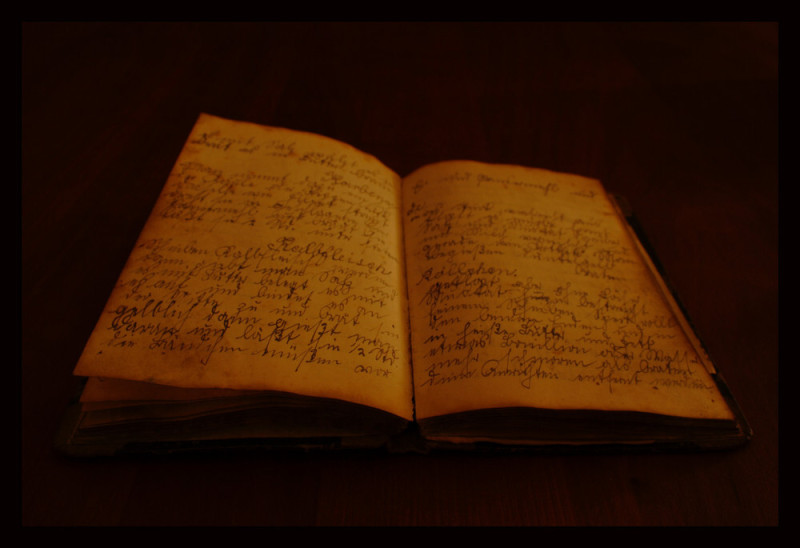

Doch eines habe ich gerettet: lose, zerrissene Blätter aus meinem Tagebuch, das ich trotz Angst und Gefahr immer noch zu führen wagte. Halbe Blätter, die ich jetzt mühsam zusammensuche und die bekunden, in schlichter, umgefälschter Wahrheit, wie ich aus beglückendem Leben in Arbeit und Frieden gequält, verfolgt, bedroht und langsam zu Grunde gerichtet wurde, wie ich vertrieben wurde mit Mann und Kind. Eine von den vielen, die nichts anderes verbrochen, keine andere Schuld auf sich geladen hat, als daß sie lebt, geboren aus jüdischen Bluten.[…] der der Himmel schon vor der Geburt das doppelte Mißgeschick auferlegt hat: Deutsch zu sein und Jüdin zugleich. Eine, die weiß und bekennt: mein Herz ist ein Archiv deutschen Gefühls, doch mit dem Deutschland von heute habe ich nichts mehr zu tun. Sie haben meine Seele verbrannt, mein Leben zerstört, meine Jugend, meinen Frohsinn, mein ganzes Ich ausgelöscht wie der Sturm ein brennendes Licht, wie das geschah: Meine Blätter mögen es erzählen.

But I did save one thing: loose, ripped pages of my diary, that I still dared to lead despite fear and danger. Half sheets of paper, which I am now painstakingly gathering together, and which reveal, in simple, falsified truth, how I was tormented, persecuted, threatened and slowly ruined from a happy life of work and peace, how I was displaced with my husband and child. One of the many, who has done nothing else wrong, has no other guilt on her, than that she lives, born from Jewish blood. On whom sky has imposed the double misfortune already before birth: to be German and Jewish at the same time. One who knows and confesses: my heart is an archive of German feeling, but I no longer have anything to do with the Germany of today. They burned my soul, destroyed my life, extinguished my youth, my cheerfulness, my whole self like the storm extinguishes a burning light, how this happened: My pages may tell it.

Hertha Nathorff, née Einstein (1895-1993) was a German pediatrician, psychotherapist and social worker, she published several works, including a book of poems. She was born in Laupheim (Baden-Württemberg) into a Jewish family. She was related to the physicist Albert Einstein, the musicologist and music critic Alfred Einstein, and the film producer Carl Laemmle. Nathorff attended high school in Ulm and, interrupted by a temporary job as a nurse during World War I, studied medicine in Munich, Heidelberg, Freiburg (Breisgau) and Berlin from 1914. After receiving her doctorate degree in Heidelberg (1920) and years as an assistant in Freiburg, she was a senior physician at the Red Cross Women’s and Children’s Home in Berlin-Lichtenberg from 1923-28, then worked in private practice and simultaneously at the Charlottenburg Hospital as head of the family and marriage counseling center. In the course of National Socialist racial policies, she lost her medical license in the fall of 1938, while her husband, formerly a senior hospital doctor in Berlin-Moabit, was granted a license for exclusively Jewish patients. During this period she worked as his receptionist.

Threatened with death in Nazi Germany, she organized emigration with the help of American relatives from November 1938, sending her 14-year-old son ahead to England on a Kindertransport. In April 1939 the couple managed to leave the country for London, and in early 1940 they continued their journey to New York. In New York, she worked as a nurse, maid, bar pianist and kitchen help – a very common fate among women with academic degrees in exile. Money and time were not enough to advance the recognition of one’s degrees. Women often took on the role of providing a living for the family. She remained a physician’s assistant in her husband’s practice, which opened in 1942 – she did not have the time and the money to get her degree recognized.

Hertha Nathorff took a very active part in the social life of the German-speaking exile community: she organized courses for emigrants in nursing and infant care and cultural events, was the founder of the Open House for the elderly, chairwoman of the women’s group, and an honorary member of the presidium of the New World Club. In the excerpts from the diary of Hertha Nathorff Berlin-New York Aufzeichnungen 1933 bis 1945, the author deals with her initial problems, disappointments and mortifications in the New World. She reports on the everyday life of refugee, on the struggle for existence, on poverty and mental destruction. Despite her longing for the places of her childhood and youth, she never visited Germany again. She never really settled in America. The homesickness remained constant.

Excerpt from the diary of Hertha Nathorff, edited and introduced by Wolfgang Benz (1987): Das Tagebuch der Hertha Nathorff. Berlin – New York. Aufzeichnungen 1933 bis 1945. Schriftenreihe der Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte, Band 54. R. Oldenbourg Verlag München, pp. 13-14.

Translation from German to English © Minor Kontor / We Refugees Archive.