עס איז שוין געװען אַרום פֿיר אַזײגער און איבער די אַרומיקע פֿעלדער האָט גענומען נישט אויף קײן קאַטאָװעס אויפֿגײן די זון. דאָס האַרץ האָט געקלעמט, װי מען װאָלט עס אַרײַנגענומען צװישן צװײ צװאַנגען. אָט גײט אויף פֿאַר דײַנע אויגן צום לעצטן מאָל די זון איבער װאַרשע! װען װעסטו װידער זען אויפֿגײן די זון איבער דער דאָזיקער שטאָט?

[…] ענדלעך האָט די באַן גערירט פֿון אָרט. עס איז געװען נאָענט צו 7 פּרי, װען די באַן האָט מיט אַ טראָציקן פֿײַפֿן זיך גענומען טראָגן איבער דער באַן־בריק, װאָס פֿאַרײניקט װאַרשע מיט פּראַגע. עס האָט זיך מיר אויסגעװיזן, אַז נישט די באַן, נאָר עפּעס אַ טײַװל פֿײַפֿט מיר איבערן אויער: “פֿיו־פֿיו! װעסט שוין מער נישט אַהערקומען! פֿיו־פֿיו! װעסט שוין מער נישט אַהערקומען…” […]

די ערשטע פּאָר מינוט נאָכן פֿאַרלאָזן װאַרשע, איז אין אונדזער װאַגאָן געװען שטיל װי צװישן מענטשן, װאָס פֿאָרן צוריק פֿון אַ לװיה. עס איז געװען אַ קילער האַרבסטיקער פֿרימאָרגן און יעדער האָט זיך געטוליעט אין זײַן דינעם האַרבסט־מאַנטל, נישט װיסנדיק פֿון װאָס עס איז אים מער קאַלט – פֿון דער קעלט אינדרויסן, צי פֿון דער קעלט אינעם אײגענעם האַרץ…

דער צוג איז געפֿאָרן פּאַמעלעך, װי ער װאָלט זיך נאָך געװאַקלט, צי ער זאָל נישט בעסער פֿאַרקירעװען צוריק אַהײם. אויף די פֿעלדער און שאָסײען האָבן זיך שוין געזען אײנצלנע מענטשן מיט פּעקלעך צופֿוס אָדער אויף װאָגנס – די ערשטע שװאַלבן פֿון טראַגישן מאַסן־געלויף, װעלכער האָט אין ברײטן מאָסשטאַב זיך אָנגעהויבן, װי עס האָט זיך שפּעטער אַרויסגעװיזן, עטלעכע שעה נאָך אונדזער אַרויספֿאָרן פֿון װאַרשע.

שלעפֿעריק האָט דער צוג זיך דערשלעפּט ביזן באַקאַנטן הינטערװאַרשעװער הײלאָרט פֿאַר לונגן־קראַנקע – אָטװאָצק. […] דער צוג האָט זיך אַלע מאָל אָפּגעשטעלט אינמיטן פֿעלד. מיר האָבן נישט פֿאַרשטאַנען, װאָס דער צוג שטעלט זיך אָפּ יעדע פּאָר קילאָמעטער. שפּעטער האָט מען אונדז אויפֿגעקלערט, אַז דער מאַשיניסט האָט אַלע װײַלע געזען פֿונדערװײַטנס דײַטשע עראָפּלאַנען, און ער פֿלעגט דעריבער יעדעס מאָל אָפּשטעלן דעם צוג, כּדי דער שׂונא זאָל מײנען, אַז די באַן שטײט סתּם אַזוי לײדיק אויף די רעלסן.

[…] די גערײצטקײט אין צוג האָט די מענטשן זײער גיך אויסגעשעפּט און עס האָט זיך געפֿילט אַן אַלגעמײנע אַפּאַטיע. עס האָט אונדז אָנגעהויבן צו מאַטערן הונגער און דורשט. כּמעט קײנער האָט דאָך נישט מיטגענומען קײן עסנװאַרג, װײַל מיר האָבן געטראַכט, אַז באַלד װעלן מיר זײַן אין לובלין.

[…] װי איבערגעשראָקענע קינדער, נאָכדעם װי עמעץ האָט זײ אַ גאַנצן אָװנט אָנדערצײלט שרעקלעכע געשיכטעס װעגן רויבער, טײַװלאָנים און בײזע גײַסטער, זײַנען מיר געזעסן יענעם גאַנצן ערשטן אָװנט פֿון אונדזער רײַזע אין די פֿינצטערע װאַגאָנעס, אײַנשלאָפֿנדיק אײנער אויפֿן אַקסל פֿון צװײטן […].

אין אומרואיקן האַלבן דרימל האָב איך דערפֿילט, אַז די באַן באַװעגט זיך. פֿאַר די אויגן, װעלכע האָבן אַלע װײַלע זיך אויפֿגעריסן פֿון מאַטערנדיקן דרימל, האָבן געשװעבט אין דער פֿינצטערניש פֿאַרבײַלויפֿנדיקע שאָטנס פֿון אײנצלנע בײמער, טעלעגראַף־סלופּעס, דאָרפֿישע הײַזער.

[…] עפּעס האָט זיך מיר עטלעכע מאָל אויסגעדאַכט – אַזוי װי דאָס געשעט אָפֿט אין קרענקלעכע נאַכט־זעאונגען – אַז די אויסגעמיטענע בײמער און אײנזאַמע הײַזער קוקן אַרײַן צו אונדז אין באַן מיט פֿאָרװאורף און אויסרײד, װי זײ װאָלטן געהאַט אַ טענה:

– און אונדז לאָזט איר אַזוי איבער?

It was already 4 o’clock in the morning and the sun was already rising over the surrounding fields. The heart ached as if it was caught between a pair of pincers. There the sun over Warsaw rose before your eyes for the last time! When will you see the sun rise over this city again? […]

At last the train moved. It was almost 7 o’clock in the morning when, with a defiant whistle, it began to drag itself over the drawbridge that connects Warsaw and Praga. It seemed that it was not the train but a devil whistling in my ear: “Fie, fie! You won’t be coming back anymore! Fie, fie! You won’t be coming back!…” […]

For the first few minutes after we left Warsaw, it was quiet in our wagon, as if we were among people returning from a funeral. It was a cool autumn morning, and everyone snuggled up in their thin autumn coats, not knowing what was colder – the cold outside or the cold in their hearts …

The train was moving slowly, as if he was still thinking about turning back home. In the fields and country lanes there were already individual people with luggage on foot or in wagons – the first wave of the tragic mass exodus, which, as it later turned out, began on a large scale a few hours after we left Warsaw. Drowsily the train dragged itself to the well-known spa for lung diseases behind Warsaw – Otwock. […] The train often stopped in the middle of the track. We did not understand why the train stopped every few kilometres. Later we were told that the engineer kept spotting German planes in the distance, and that that is why he stopped the train every time, so that the enemy would think that the train was just standing there empty on the tracks.

[…] The irritation in the train exhausted the people very quickly, and one felt a general apathy. Hunger and thirst began to torture us. Hardly anyone had taken any food with them because we thought we would soon be in Lublin.

[…] Like frightened children who had been told terrible stories about robbers, devils and evil spirits all night, we sat in the dark wagons that first evening of our journey and fell asleep with our heads on the shoulders of our neighbour […].

In my restless half-sleep I felt the train moving. In front of my eyes, which were repeatedly torn from a torturous dream, shadows of individual trees, telegraph poles, village houses floated past in the darkness.

[…] Again and again I imagined – as often happens with ailing night visions – that the passing trees and lonely houses looked into the train at us with reproachful and blaming looks, as if to say:

– And you leave us like this?

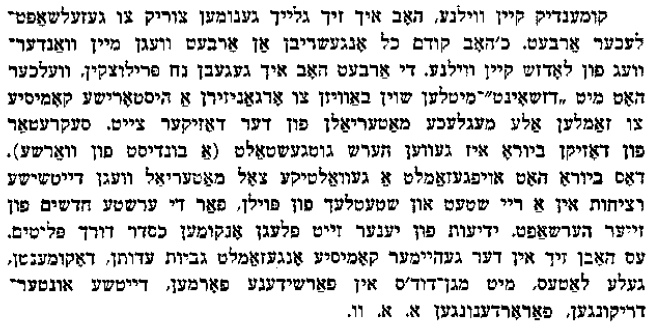

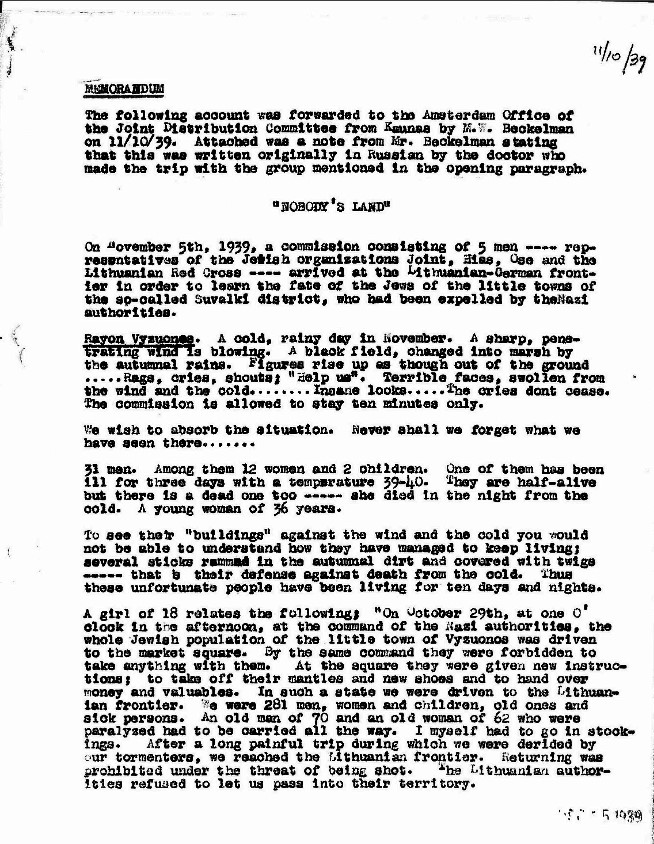

Pinkhas Shvarts was a member of the Bund, writer and correspondent of the Yiddish Folks-tsaytung (People’s newspaper) in Warsaw and brother of the famous chronicler of the Holocaust in Lithuania, Herman Kruk. He was one of the few Polish-Jewish writers who managed to get a seat on the so-called journalist train, which left Warsaw for Lublin on the night of September 5-6, 1939, to escape the German invasion. He tells of the fears, guilty conscience and (self-)reproaches that accompanied and plagued the refugees on their flight.

The journalists reached Vilnius on October 10, 1939 after a long, dangerous and erratic journey. Arriving here, the Jewish refugees did not hesitate for long. In November 1939, a group of refugee fellow writers and journalists founded the Committee for the Collection of Material on the Destruction of Jewish Communities in Poland in 1939, probably the earliest Jewish historical commission in Eastern Europe, which, in the shadow of German crimes, secretly began to document the destruction of Polish Jewry since September 1939. Pinkhas Shvarts survived the Shoah by escaping via Vilnius in the direction of New York, and in 1957 became a leading member of the Bund‘s World Coodinating Committee.

Excerpt from:

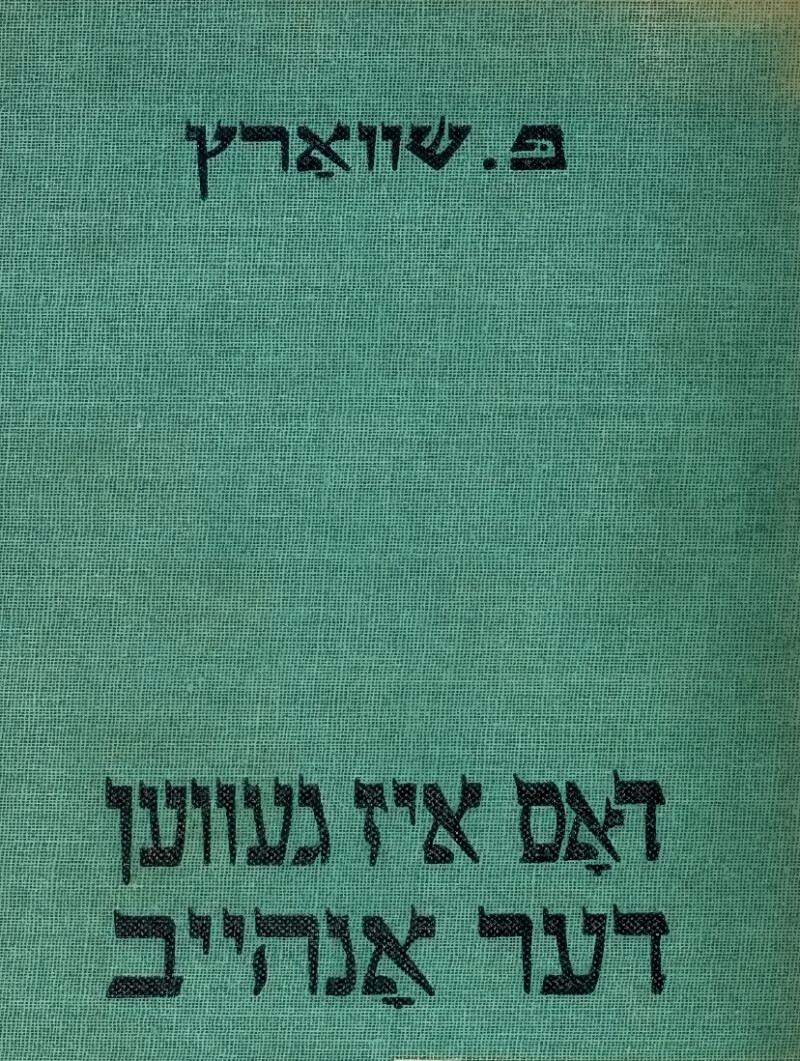

Pinkhas Shvarts, 1943: Dos iz geven der onheyb, New York: Farlag “Arbeter-ring”, pp. 59–72.

From the Yiddish Book Center’s Steven Spielberg Digital Yiddish Library.