Law, as we know, is socially constructed and that both offences previously regarded as a crime, as well as those not previously deemed so, for example drug consumption today, or the reverse, homosexuality, are impacted both by the governments of the day and that nebulous concept, public opinion. Indeed, it is one of the many disturbing aspects of the Holocaust, as theologian Richard Rubenstein highlights, that ‘The Nazis committed no crime at Auschwitz since no law or political order protected those who were first condemned to statelessness and then to the camps.’ It is in this context that I will explore the origins, as well as the social and bureaucratic history of the term ‘illegal immigrant’ and its derivatives and close relations, ‘illegal alien’ and ‘illegal immigration’. These specific labels are of relatively recent usage coming particularly from the Nazi era, but they are now used with increasing frequency. To quantify, in 2005 a Google search for ‘illegal immigrants’ produced 17 million hits. I repeated that exercise recently and the two words in combination produced a staggering 124 million hits. I want to explain why these phrases, and their abbreviated and even more abusive version, ‘illegals’ (producing a mere six and a half million hits), have become such common currency and what the wider implications of this are not only in the treatment of migrants but more generally with regard to human rights.

With Mexican and other central American migrants in mind, the late Auschwitz survivor, human rights activist and Nobel Prize winner Elie Wiesel, pithily commented:

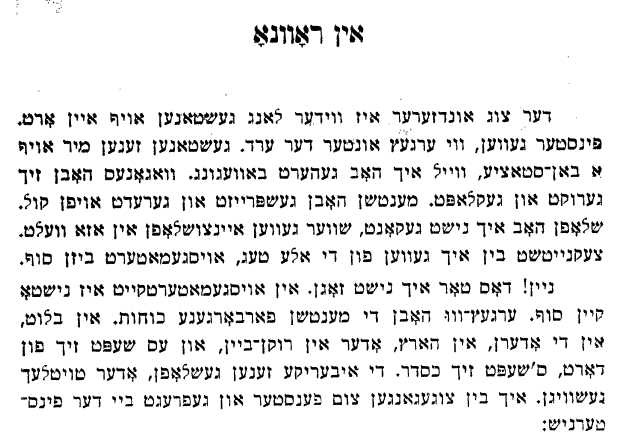

You who are so-called illegal aliens must know that no human being is ‘illegal’. That is a contradiction in terms. Human beings can be beautiful or more beautiful, they can be fat or skinny, they can be right or wrong, but illegal? How can a human being be illegal?

In her Excitable Speech: A Politics of the Performative, Judith Butler refers to the ‘jarring, even terrible power of naming… the power of the name to inaugurate and sustain linguistic existence, to confer singularity in location and time’. The philosopher adds that it is the ‘sedimentation of its usages… a repetition that congeals, that gives the name its force’.

It remains that modern scholars, influenced too strongly by enlightenment ideas of human progress, have been hesitant until recently to explore the lasting force of the irrational in history. The pioneer against that lacuna was Norman Cohn, author amongst other classic studies of Warrant for Genocide. Cohn’s wider concern, with the Holocaust firmly in mind, was ‘to study the processes by which a given category of human beings comes to be dehumanized, that is to say, seen not to be fully human; and also, the consequences that commonly follow from that… [and] the various ways in which feelings of human solidarity and compassion are suppressed and the sadistic and destructive potentialities of human nature are brought into play.’

It is easy to mock, discriminate against, subjugate, persecute, and even exterminate those who you regard as naturally inferior or essentially ‘other’ to yourself. And returning to Judith Butler and her reflections on hate speech, she adds that ‘Clearly, injurious names have a history, one that is invoked and reconsolidated at the moment of utterance’. To understand the power of ‘the name’, she insists, requires a knowledge of its ‘historicity’. By this, she explains, ‘as the history which has become internal to a name, has come to constitute the contemporary meaning of a name’.

In the field of migration, what is unusual, perhaps unique, is the power of naming that makes a whole category of people, before they have done anything, including and especially their actual presence in a country, illegal. Pre-civil war slaves, for example, in America, and even free blacks, were treated in all ways as lesser beings. But they were not illegal. Similarly women, whilst treated as inferior in most western law and patriarchal society until well into the twentieth century and now beyond, were also never simply ‘illegal’.

In the early modern era world migration, whilst increasing exponentially, was hampered more by the cost and availability of transport across land and sea much more than state control of entry. Before 1914 the free movement of peoples across borders was still the norm. The tendency to de-humanise and indeed monsterize migrants and minorities – as with the medieval representation of Jews as Satanic pigs, and the Irish and blacks as ape-like – has a long and murderous history. What was missing, however, was adding the qualifying adjective ‘illegal’ to the more, in theory, neutral terms immigrant, emigrant or alien.

Mae Ngai, author of Impossible Subjects, an analysis of so-called ‘illegal aliens’ and the making of modern America, starts her study in the 1920s and especially the 1921 and 1924 quota laws which discriminated against certain national groups on the basis of race. Ngai argues convincingly that the term ‘illegal alien’, or ‘illegal immigrant’ could only develop after a nation had started imposing systematic control of migrants across its border. The same is true of Britain. A statistical analysis of the terms used in both parliament and the press concerning the heart of the Aliens debate is revealing. Not once across the press of the country was the phrase ‘illegal immigrant’ or ‘illegal alien’ used.

From the late nineteenth century onwards, western immigration control has been a transnational movement with ideas and regulations freely borrowed from nation or regional state to another. Aristide Zolberg puts it neatly as a “kind of global immigration-control ‘arms race'”. By 1919 Britain was at the forefront and had passed the most draconian measure of control in the western world. America would not be too far behind, however, and its quota laws of 1921 and 1924 reflected a new world order in the movement of peoples across borders.

The quota laws were aimed especially at Jews, Slavs and Southern Europeans who were now deemed racially undesirable. It represented the triumph of Anglo-Saxonism in American immigration policy with those of so-called Nordic origin given utter preference. With contemporary resonance, the smugglers were described by the restrictionist American Saturday Evening Post as ‘water-front rats, cutthroats and racial outcasts’.

In terms of the language of exclusion and control, however, whilst those coming into America were often described as doing so ‘illegally’, ‘illegal alien’ or ‘illegal immigrant’ had not yet solidified as everyday terms. Yet the differentiation between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ migrants, based largely on race, had been firmly and irrevocably established. In it southern border those who were not covered by the quota laws were still treated as illegal if they did not have sufficient paperwork or who had not been subject to health screening on the border. From the 1950s onwards, it was these migrants who largely became the focus of debate about illegality and who were subject to a series of increasingly draconian measures. These included the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigration Responsibility Act of 1996. This was indeed the first law to explicitly include the term ‘illegal immigration’ and marked a new stage in its evolution of which the Trump era is simply a cruder manifestation.

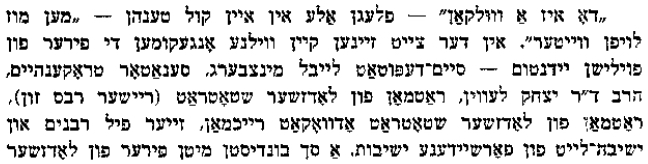

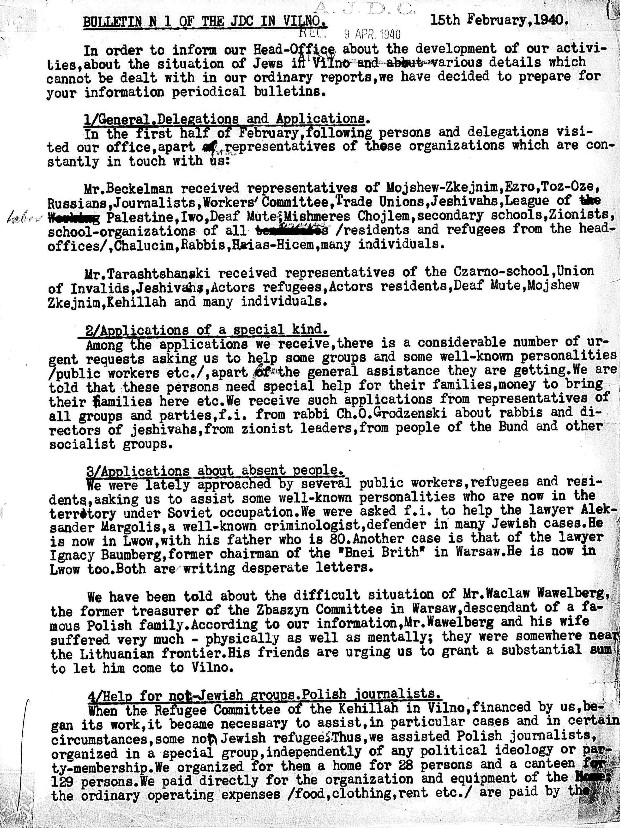

But the term illegal immigration really came of age under British Mandate Palestine and the growing Jewish refugee crisis. In late 1933, the High Commissioner for Palestine used a variety of terms to describe those who were coming in, including ‘illegitimate immigrants’, ‘illegal settlers’, and people engaged in ‘illicit settlement’. There was also increasing use of the phrase ‘illegal immigrants’ and the rhetorical device of linking ‘illegality’ to immigration had been established. With increased Jewish migration to Palestine from Germany and elsewhere, usage of the term would intensify and develop an increasingly conspiratorial tone: the words ‘Illegal’ and ‘Immigrant’ were now contiguous.

By 1935 Jewish immigration to Palestine was again causing concern to the British colonial authorities and ‘Jewish Illegal Immigration’ had become bureaucratically standardised with capitalisation to ensure the firmness and certainty of this new label. It was now regarded as organised ‘traffic’ rather than the spontaneous movement of individuals. Detention pending deportation was used as deterrence. A 1939 Colonial Office paper set the template for what would be an even more intensive performative struggle over the rights and wrongs of immigration policy in Palestine during the war and after. Like many defending immigration controls, emphasis was placed on ‘the interests of the inhabitants’ as against the ‘entry of myriads of immigrants’ who would, unless stopped, ‘flood the country indiscriminately’ through ‘mass invasion’. Indeed, it was, argued the Colonial Office, ‘necessary to be clear about one thing. This illegal immigration traffic is a dirty, sordid, crooked business.’

With the outbreak of war and the fast deteriorating situation of European Jewry, the discourse of the Colonial Office on ‘illegal’ immigration not only persisted but intensified in its animosity. Indeed, the conflict allowed ever more conspiratorial aspects to develop as it did after, most notoriously with the ship Exodus 1947 carrying close to 5000 Jewish refugees which was turned back to Europe. Sadly, such desperate journeys with many forced by the British to the island of Cyprus remain unconnected in memory work with those of the Nakba or Palestinian tragedy of forced migration with the creation of the Israeli state.

If making such linkages, however desirable, seem unlikely given the dismal politics of the contemporary Middle East, it is equally hard to envisage the Exodus 1947 story being placed alongside more recent narratives of forced migration across the ‘merciless sea’. So far, the exclusive tendencies and partial amnesia associated with its journeying have largely precluded such comparisons which is the underlying philosophy of my Journeys from the Abyss (2017), my attempt to connect Holocaust studies and forced migration studies.

It has been estimated that from 1933 to 1948 108,000 Jewish ‘illegal’ immigrants came to Palestine in 116 vessels, hundreds perishing in the process. In 2014 alone, double that number of undocumented migrants came to Europe by sea, thousands drowning in the Mediterranean attempting to do so. In 2015 these numbers were quadrupled, many linked to the Italian island of Lampedusa. It is a small, sparsely populated and bare space. Ominously, with regard to its later function as a reception then detention camp for migrants in the late twentieth and early twenty first century, it had a pre-history, serving as ‘a penal colony in during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries’.

There are no definitive figures for those who have died migrating to Europe using the Mediterranean. Using media and NGOs, the monitoring group Fortress Europe argued that between 1993 and 2011, close to 20,000 died en route. Since then the numbers have gone up alarmingly. It is often assumed that desperate migrants made a conscious choice to come to Lampedusa as the closest piece of European land from Africa. Whilst in the early stages of this movement in the 1990s, there was an element of truth in such assumptions, it has not been the case subsequently. Since the early twenty first century, it has been emphasised that migrants ‘did not arrive of their own accord’: they thus did not choose Lampedusa, but were directed and diverted there by the Italian authorities as a way of controlling the flows of migration which were both increasing in numbers and diversifying in places of origin.

Lampedusa had become a ‘border zone’, a place which had ‘essentially become detached from the rest of Italy’. It is, in the words of Alison Mountz, one of many ‘stateless spaces’. The Sicilian Channel had, in effect, ‘become an outer border of the European Union’, and Lampedusa was the focal place/non-place where attempts were made at controlling the flow of unwanted ‘illegal’ migrants. There is a parallel in Lampedusa to Exodus 1947 which the British and Palestinian authorities wanted to make into a salutary example as well as a specific case of refused entry to ‘illegal’ immigrants. In both cases security and economic fears have run alongside humanitarian concern. In the case of the Jewish ‘illegal’ immigration, the British tried (and failed) to impress the world that those embarking on such journeys, and especially the organisers, were doing so at the expense of genuine, legitimate refugees. Today, similar dynamics are at work with the focus of European bodies and politicians being on the ‘criminal’ smugglers and the need to curtail their activities, including the destruction of boats used to carry the migrants.

It has been noted that of the 50,000 plus migrant deaths in transit recorded (and two thirds are not), for as many as one in five the region (let alone the country) of origin is unknown. That so many deaths literally leave no trace in a world of instant communication and constant surveillance reflects the utter obscurity and marginality of so many migrants today. The Mediterranean, for example, has been described as the busiest ocean in the world, yet thousands have drowned in it. Against that invisibility is the desire of many NGOs, journalists, campaigners, academics and others to give restore individuality to the migrant. Yet EU regulations force migrants into certain narratives in order to gain asylum.

Perhaps the most desperate attempt to ‘perform’ refugeedom is the desire to show innocence through the presence of young children on these boats. Abdul Azizi, and 26 other refugees from Afghanistan and Syria boarded a boat from Turkey aiming for Greece. After two hours their engine failed and a Greek coastguard vessel ordered them to return to Turkey. ‘We said the boat had broken down. And we took the babies and held them above our heads, to show that there were children on board. But they didn’t listen’. Their boat was towed towards Turkey and then began to sink:

‘The women and children were in the [hold] and we went to try and get them… Everything happened so quickly. There was no time to save our children. We had arrived in Europe. We were refugees. But in a flash I had lost my child and my wife.’

After 1945, Jewish survivors of the Holocaust performed their persecuted state through adopting, according to the British authorities, a ‘Belsen’ pose. In the first decades of the twenty first century, the climate of distrust is such that migrants are forced to exhibit their children to show they are not a threat to the receiving countries.

In the detention centres of the island and in its everyday life, the migrants have both resisted and formed alliances with the local inhabitants. In February 2014 this led to the creation of the Charter of Lampedusa which was not ‘intended as a draft law’ but as the expression ‘of an alternative vision’ where ‘Differences must be considered as assets, a source of new opportunities, and must never be exploited to build barriers’. Lampedusa has also acted as a source of identity for those who have found asylum beyond its shores. It has led to groups including ‘Lampedusa in Berlin’ using the solidarity of this experience to campaign for better treatment of migrants at all stages of the journey.

In the politics of performativity involving both Exodus 1947 and contemporary boat people, history matters. On one level, they share a common bureaucratic past and the construction of the ‘illegal immigrant’. That there are few if any links made between the boat migrants of the twenty first century and the ‘illegals’ of the 1930s/1940s, reflects largely the self-contained nature of Holocaust studies, including Jewish refugees from that era, and the ahistorical nature of forced migration studies. Exclusive readings of the past hinder the universalism proclaimed in the Charter of Lampedusa that ‘As human beings we all inhabit the Earth as a shared space’. It stands for ‘global freedom for all’, recognising that ‘The history of humanity is a history of migration’, admonishing ‘No Illegalisation of people: migration is not a crime’.

But there is more: in the world of Trump and Brexit it becomes normalised for migrant children to be incarcerated and even to die in captivity and for those legally settled in Britain for decades to lose their jobs, housing, to die through refusal of medical treatment and to be deported as a result of a ‘hostile environment’ towards so-called ‘illegal immigrants’. The ‘illegal alien’ or the ‘illegal immigrant’ has always been a cultural construct that has been imposed by politicians, civil servants and the media to keep out those they do not want, often for reasons of racism, including antisemitism. In America, the slogan ‘what part of illegal don’t you understand?’ has become everyday discourse. Once a people become ‘illegal’, as Jewish history shows us, anything is possible.

To close my lecture: how long have migrants been labelled ‘illegal’? The answer is historically – not too long – but ethically, far, far too long.

The recorded lecture by Prof. Tony Kushner can be watched in full length here.

Tony Kushner is Professor at the Parkes Institute for the Study of Jewish/non-Jewish Relations and History Department at the University of Southampton. His main research area is British Jewish history in the late 19th and 20th centuries, with a focus on the social history of British Jewry and immigration issues. He has a strong interest in the Holocaust (particularly liberal democratic reactions and post-war representation), refugee movements, immigration and ethnicity in modern British history, and general issues of history, representation and memory culture.

A short movie summarizing the event “Experiences of Flight in Past and Present. Continuities and Discontinuities” can be watched here.