Boat Refugees in Sicily

In the year 2014, the number of so-called boat refugees reached over 170,000 people and rose in the year 2017, to 199.356 refugees who were arriving on the coast of Sicily from across the Mediterranean.

In 2018, in contrast, only 23,270 refugees were stranded on the coast of Sicily. A shockingly low number, which had nothing to do with a supposed decline in the migration movement, but rather quite clearly with the political decisions and measures taken at an EU and Italian level. Through agreements with transit countries such as Libya – destroyed by anarchy and civil war – enormous migration bottlenecks have emerged, accompanied by boundless human rights violations against migrants and refugees.

“The readiness of the EU to spend money working together with armed militias and corrupt governments ‘elsewhere’ while consciously allowing for migrants to be held captive or drowned at sea, is a clear refusal of a responsibility towards human rights.”

Afterall, the decision by the Italian government to close the ports led to an increase in the number of migrants who were brought back to the coast of Libya: in total, since June 2018, there have been over 10,000 people captured at sea from the Libyan coastal guard, ever since the “politics of closed ports” has been in effect. Still, people are attempting to come to Europe over the Mediterranean Sea. Their misery – after an often long and traumatic journey – is so high, that even the most terrible stories of the journey to Sicily no longer discourage them. Through the criminalization of emergency sea rescue, seafarers and NGOs and their rescue ships are also jeopardized. This policy, which clearly increases death in the Mediterranean Sea, came to an end with the new regime in Italy since mid-September of 2019. A resumption of the systematic state-run emergency sea rescue in the south of the Mediterranean is all the more urgent as more people continue to drown.

“If we do not intervene soon, there will be a sea of blood.” This is how Carlotta Sami, the speaker for the UN refugee agency UNHCR in Italy, described the challenge and the urgency of the situation in the Mediterranean between Libya, Tunisia and Sicily. If one were to look back almost nine years, it becomes apparent that despite several appeals, very little has changed:

“I’m becoming more convinced that European policies on immigration consider this offering of human lives as a way to restrict the flows of people, or even as a deterrent. But, if for these people a trip on a boat is still the only possibility of hope, I believe that their death at sea must be a reason for Europe to feel ashamed and dishonoured.”

Among the few who reached the coast of Sicily in 2018, there are many persons in need of protection: unaccompanied minors (3,536 in the year of 2018), pregnant women or women with under-aged children, victims of torture, slavery and extreme exploitation. The stay in Italy should minimize these conditions, this is not always the case, however. The lack of specific services and support measures or the interruptions of access to services as well as the sharpened insecurity regarding their legal status count among the main reasons. An additional difficulty is that most people see Sicily more like a transit than a place of refuge and either try to end up in the north of the county or in another European country.

Sicily as a space of immigration and refuge or as a gateway for Europe?

In the course of its migration history, Sicily has experienced different phases of immigration and emigration, where the transnational relationship to Tunisia is of a hundred-year old importance. Furthermore, from the 1960s and 1970s people came as migrant workers from the Maghreb, but also from different countries in Africa and Asia. During this time, Sicily developed into a gateway to Europe and thus into a transit space for migrants heading to the prosperous regions of northern Italy or northern Europe.

Since the 1990s, Sicily has experienced a clear transformation towards becoming an immigration region for migrants from the EU and Asia as well as a sanctuary for refugees, who came with boats from across the Mediterranean to Sicily. During the 1990s, Sicily became the destination of a consistent migratory process, comparable to northern and middle Italy. In January 2018, the number of the foreign populations in Sicily reached 193.014 people, i.e. 3.8% of the total Sicilian population.

The high heterogeneity of immigrants is clearly visible: Romanians (almost 30%), followed by Tunisians (10.5%), Moroccans (7.8%) and Singhalese (7.0%), Albanians (4.5%), Bengalis (4.3%), Chinese (3.9%), Poles (2.8%), Filipinos (2.8%), Ghanaians and Nigerians (both 2.0%), Senegalese (1.7%), Mauritanians (1.6%), Gambians (1.3%), Pakistanis (1.1%), Ukrainians (1.1%), Indians (1.1%), Germans (.9%), Malaysians (.9%) and Bulgarians (.7%).

Palermo – City of Accommodation

Palermo, the Sicilian capital, is the city with the highest foreign population in Sicily. In January 2018, the province of Palermo, closely followed by Catania, reached its high point of around 36,000 foreigners.

Even though overall, Sicily still does no occupy the top place in the rankings of destination locations for migrants and refugees who came across the sea, Palermo is increasingly developing into a preferred destination. Thus, Palermo is not just a place of (transitory) refuge, but also of immigration: this is demonstrated by the numbers of the composition of immigrating people in Palermo. The largest group in 2018 are 7,213 Romanian immigrants, mostly women, followed by 5,455 from Bangladesh, 3,635 from Sri Lanka, 2,888 migrants from Ghana and 2,265 from Morocco. These numerically largest groups show the diversity of migration coming from Europe, Asia and Africa.

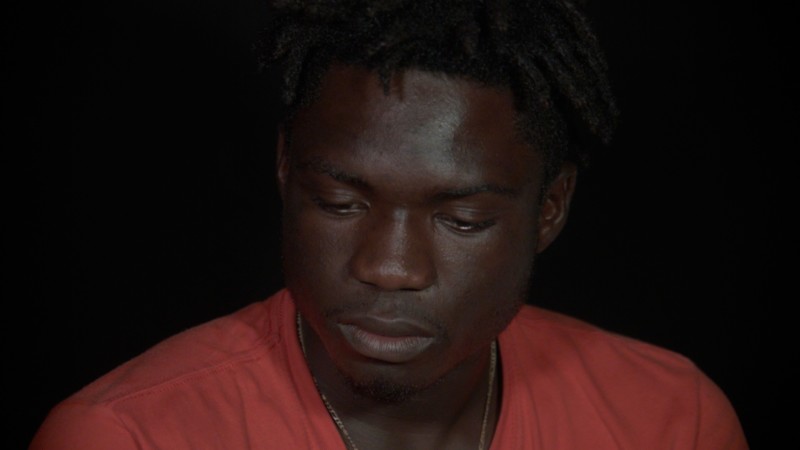

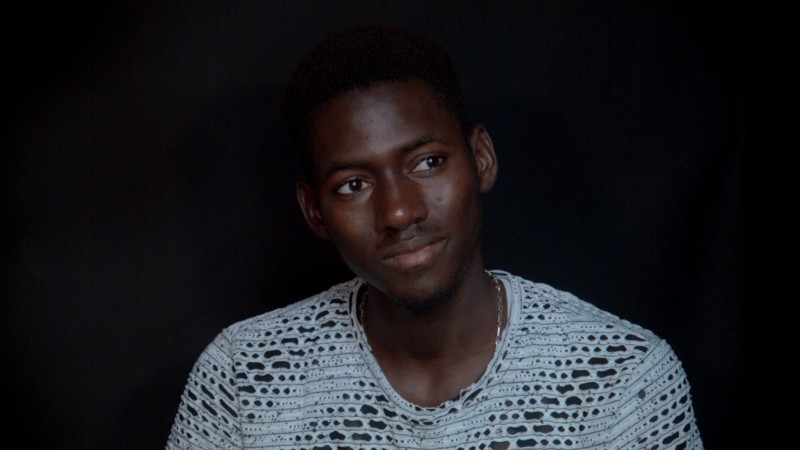

Palermo is an important place of accommodation for unaccompanied under-age refugees in Sicily. According to statistics of the year 2018, 90% were male and on average 17 years old. Looking at Sicily as a whole, almost all minors come from Africa. The largest group of young refugees in Palermo comes from Gambia, followed among others, by Eritrea, Mali, Ghana and Tunisia.

In June 2019, We Refugees Archive worked with very young migrants and refugees in Palermo, who, almost without exception, came as 16 to 17-year-olds from Gambia, Guinea, Mali, Nigeria and Somalia across the Mediterranean to Sicily. Whether they can stay in Palermo remains unknown. They rarely describe the diverse motives for their migration as flight, even though the descriptions of their journey to Sicily do resemble the known terrible experiences of flight. They experience and value their support network in Palermo, meet with friends at the Ballorò quarters, have mostly learned the Italian language and graduated from secondary school. They experience a Palermo which, from their perspective, is much better than many other cities of the Italian north and is not a place of refuge for them, but rather a possible final destination.