As part of the Berlin Blockade, the U.S. occupiers evacuated all Jewish DPs from the city. Some of them decided to stay in Berlin.

Yeshayahu Zycer plays in the snow with his teachers, Margot and Leonhard Natkowitz, at the Schlachtensee displaced persons camp. © United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Francoise Bielinski Sitzer, 38299

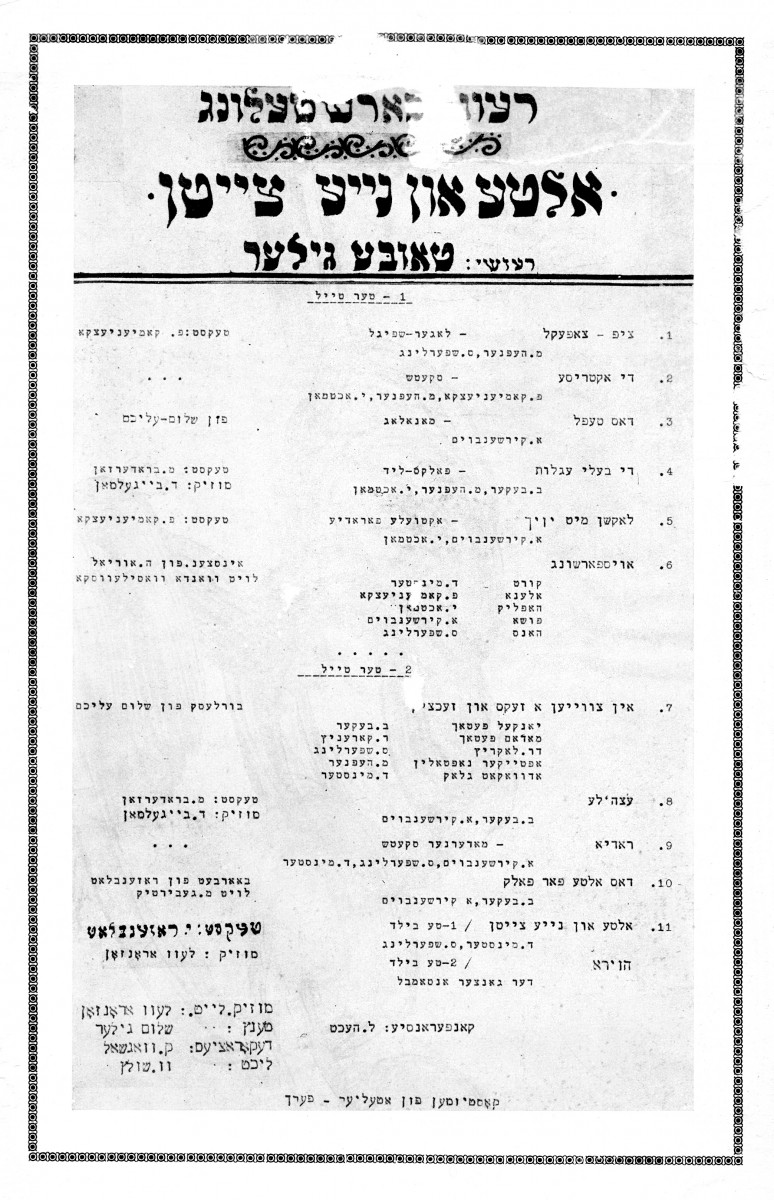

Playbill for the theater show “Old and new times”, a Yiddish play, given by the “Baderech” theater

High school students at the Schlachtensee displaced persons camp study in a classroom © United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Francoise Bielinski Sitzer

Flyer for the DP theater “Baderech”

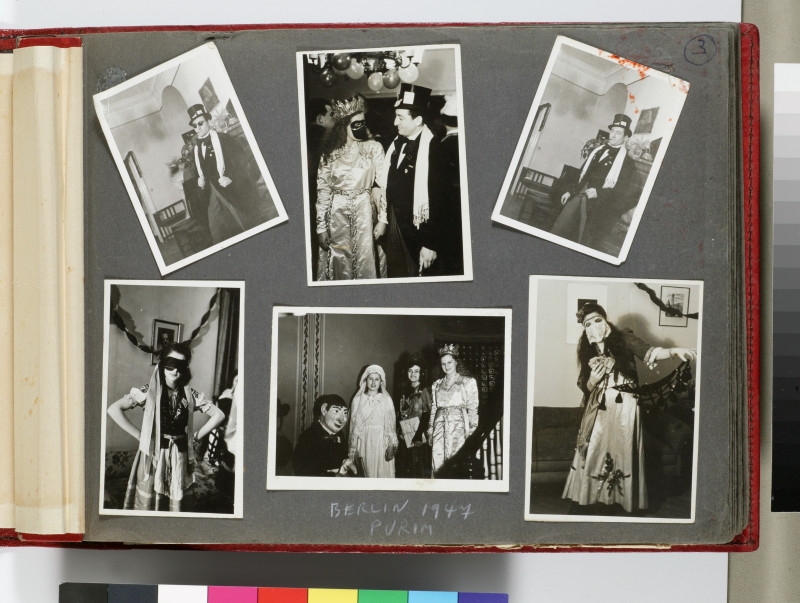

“Purim 1947”: Photo Album by Wolfgang (Dixi) Heim, Berlin, Kladow, Biberach, Köln, Marseille, Zürich, ca. 1946-1948 © Jüdisches Museum Berlin, Inv.-Nr. 1999/217/6a, Schenkung von Wolfgang Heim

Jewish circumcision ceremony (Brit Milah) in „Düppel-Center“ © United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Mayer & Rachel Abramowitz, 58434

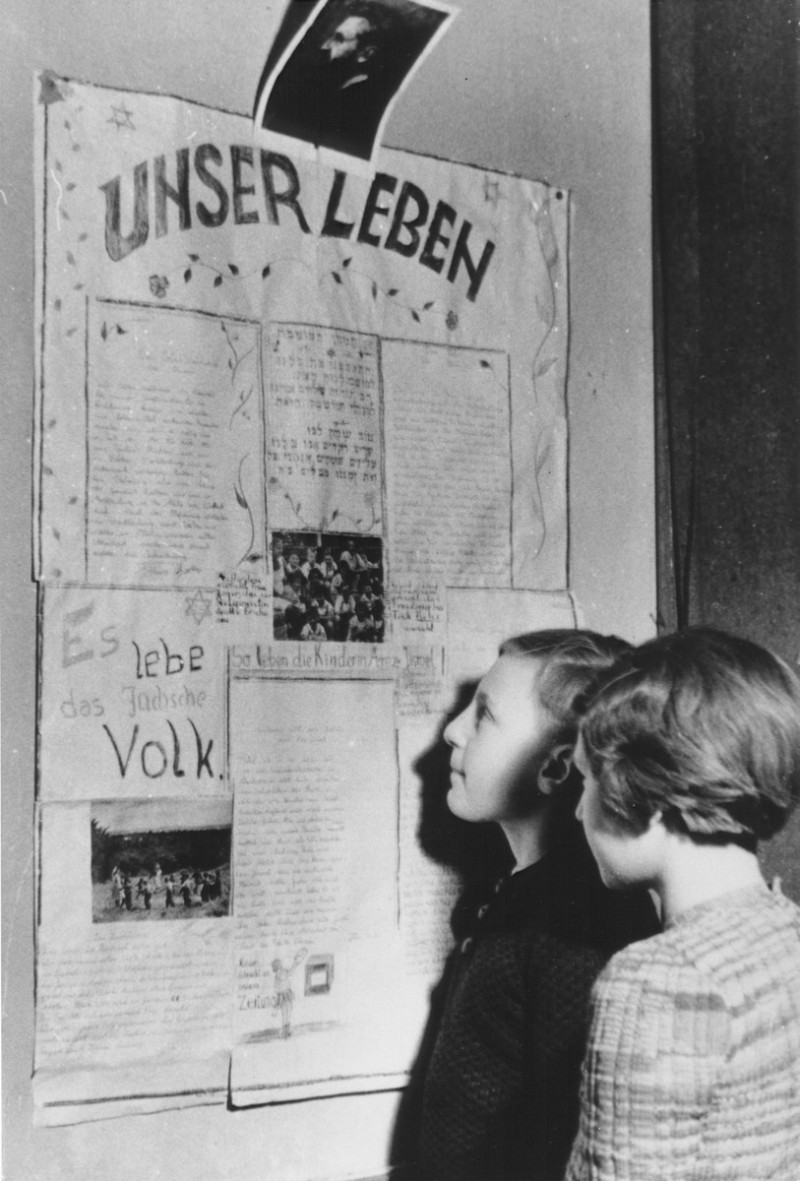

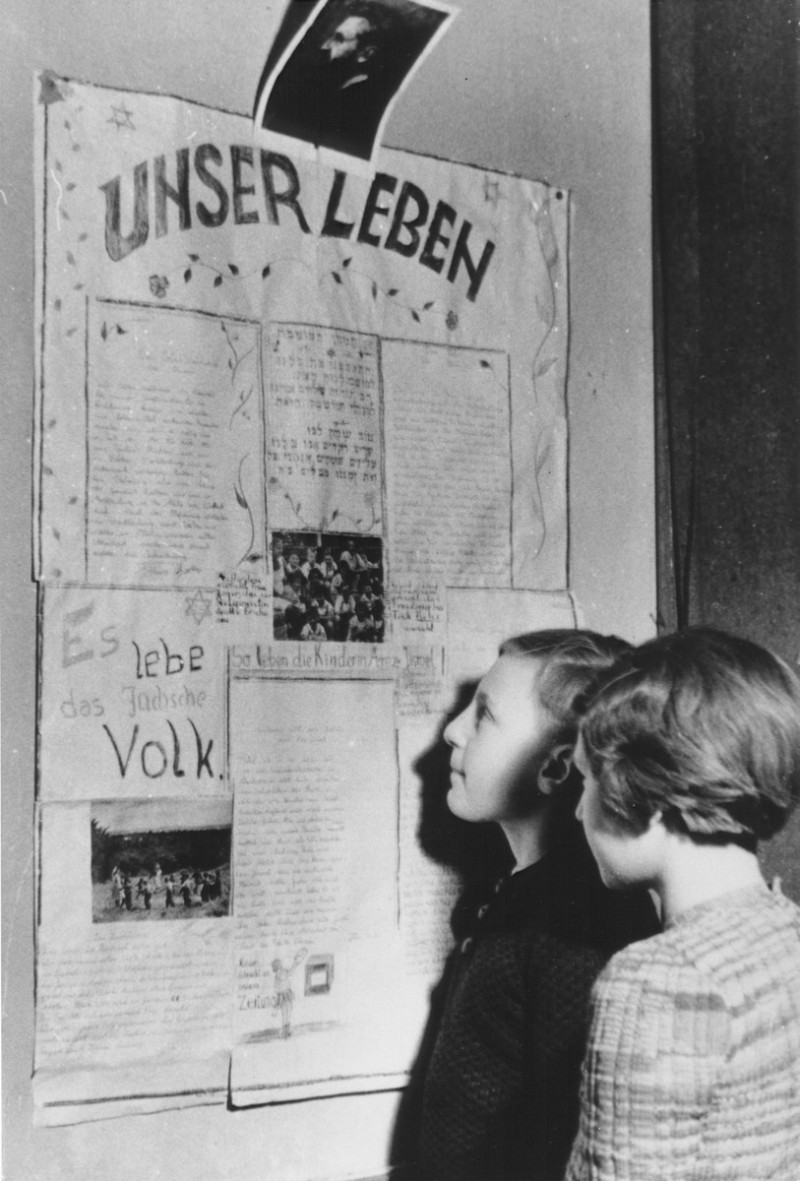

Children reading the camp newspaper Undzer Lebn, 1946 © United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Mayer & Rachel Abramowitz, 48780

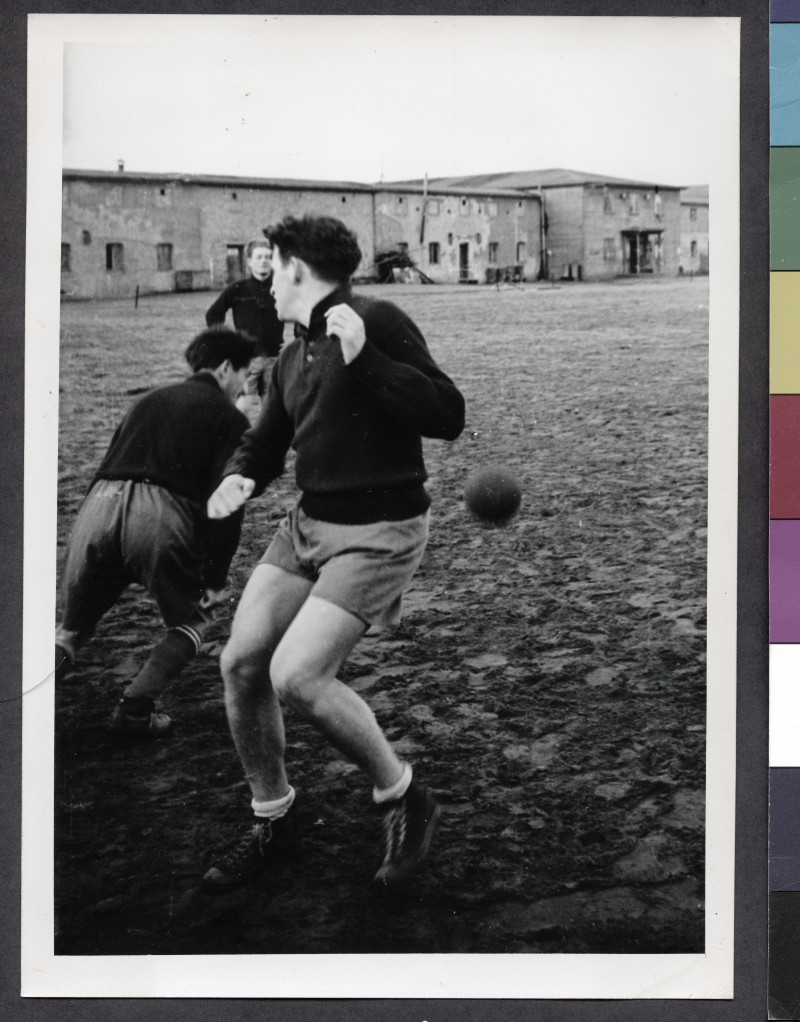

Children doing sports, ca. 1946 © American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee Archives, NY_02741

Soccer game in the DP camp „Düppel-Center“ © American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee Archives, NY_50747

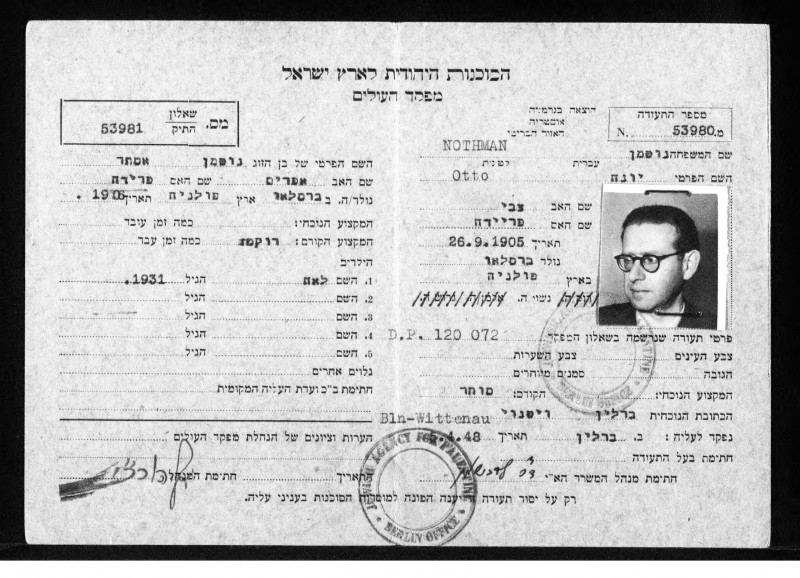

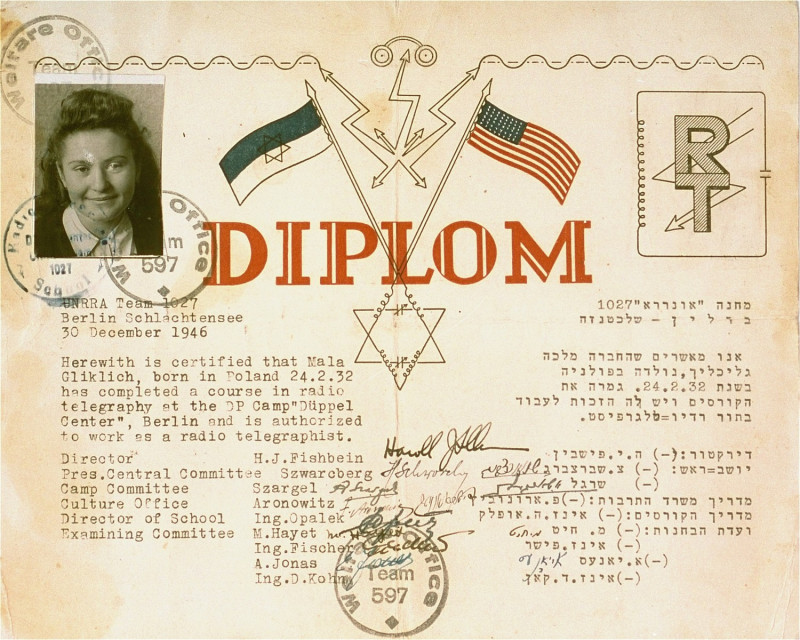

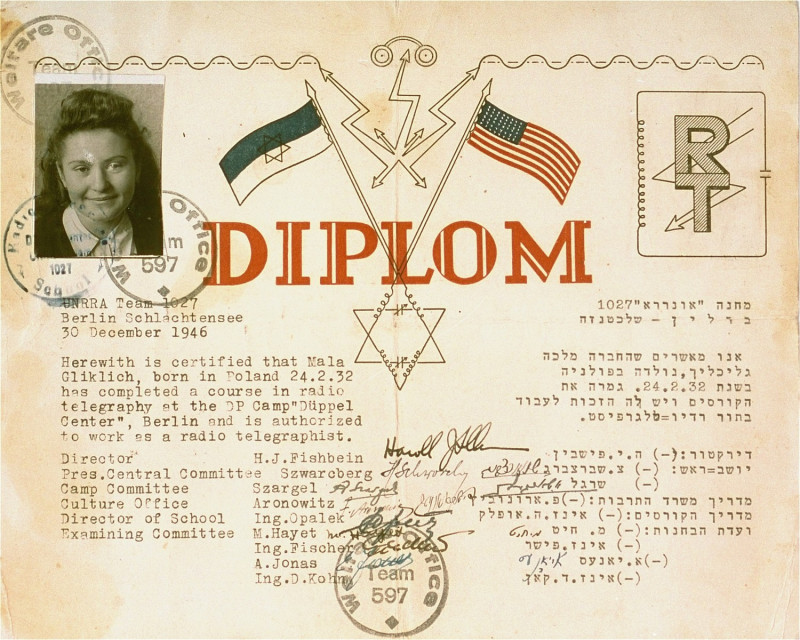

ORT degree for Malka Gliklich in radio telegraphy, 1946 © United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Lucy Gliklich Breitbart, 04210

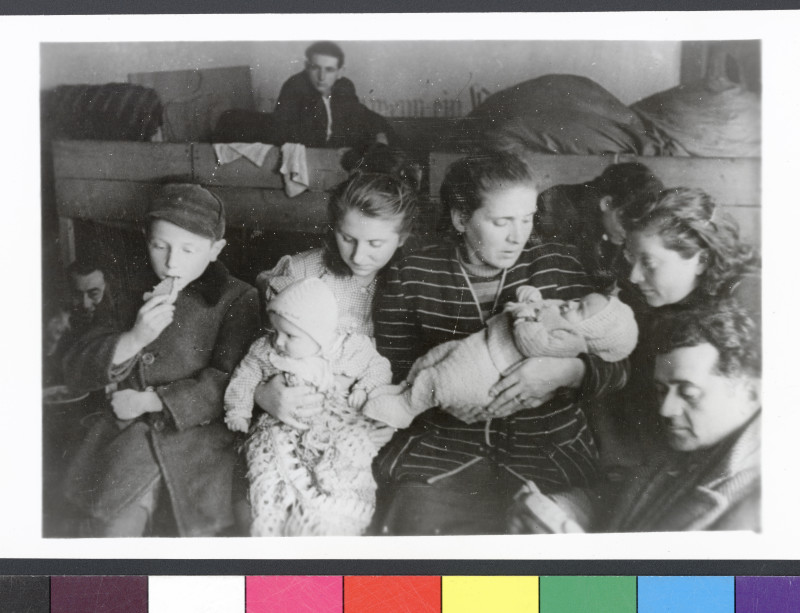

Families in a shelter led by Joint in Rykestraße, 1945 © American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee Archives, NY_07156

“What always matters to us is to overcome the shadows of yesterday. […] We need artistic self-actuation, we have the right to individualism: for years we were supposed to die as a monolith; now the time has come when we want to live as a people! Our little theater on the outskirts of Berlin, the transit station on the way to a new life, is the first step towards this.”

An actor from the DP theater group “Baderech” in the Jewish newspaper Der Weg, September 5, 1946

At the end of 1946, the U.S. military government temporarily banned onward emigration, which meant that the refugees were stranded in Berlin. Circumstances made it difficult to flee to Berlin, the underground organization Brichah (“Escape”) abandoned the route from Berlin to Szczecin (Stettin), and hardly any refugees arrived since. Yet, the DP camps developed into small towns with schooling, vocational training, and cultural, political, sporting, and artistic activities.

Art played a major role in the DP camps: in literature, theater and music, people dealt with the traumatic experiences of the Shoah and the present in Berlin. Most of the works were written in Yiddish, a language that gained in importance as a carrier of memory and identity. In the first five years after the end of the war, 140 newspapers and magazines and about 30 volumes of prose and poetry were published in Yiddish in the U.S. occupation zone alone.

Children were of paramount importance in the DP community. The Shoah left many DPs without family members. Few children had survived the concentration camps. Due to a high birth rate and the arrival of whole families who had survived in the Soviet Union, the number of young DPs increased rapidly after 1945. Immediately, kindergartens and schools were established in the camps. The relief organization ORT (Organisation – Reconstruction – Training) offered practical vocational training to adults in order to prepare them for a life after Germany. In the camp “Düppel-Center” in Zehlendorf, a people’s university was established with daily lectures.

The first performances of the Yiddish-language theater Baderech (“On the Way”) took place at the Lumina Cinema in Zehlendorf. The plays received good reviews in Berlin newspapers. In addition, there was the Herzl Cinema in Zehlendorf, which showed Yiddish films and enjoyed great popularity. Sports clubs were founded that organized inter-camp sports events.

“Our cultural work

While before the war we had a unified society consisting of people who lived anarchic lives, now we have a diverse society. We have children who have gone through more than adults, children who have been torn far from Yiddishkeit, children who speak different languages, adults who have gone through ghettos and concentration camps, and partisans, people who masked themselves and hid as Aryans. But despite all these difficulties, we still managed to organize and realize a cultural work in the camp. While the camps in Bavaria have contact among themselves, Munich can guide them and give various instructions, here in Berlin we are alone and have to organize everything ourselves, from our own strength and a few people we carry out the work.”

Undzer Lebn, January 15, 1947

Many of the predominantly Eastern European DPs were more religious than the more secular German Jews. Religious committees in the DP camps offered counseling on religious matters and conducted religious ceremonies and visits to the sick. Synagogues and kosher kitchens were established in all three camps.

A broad spectrum of political parties formed in the DP camps. The parties more or less agreed that a Jewish state had to be created. They disagreed on exactly how it should be founded and what it should look like. Some DPs, including many women, joined the Zionist paramilitary underground movement Haganah (“Defense”) already in Berlin. This movement fought for the establishment of a Jewish state in British Mandate Palestine.

In August 1946, the first issue of the Yiddish language camp newspaper Undzer Lebn appeared, which was to be the central organ of camp life. Often written humorously, the authors devoted themselves to topics of social, political, and cultural interest. The newspaper was published at irregular intervals and had a circulation of up to 3,000. In addition, numerous Yiddish-language publications appeared in the DP camps. Separate Yiddish libraries were established.

“BeDerekh, HaNoder, a bit strange names for theater. But these names are not accidental. The actors wanted to underline with the names exactly their temporary existence and justify their hurried work, because there is no hall, a stage, costumes, wigs and in general material is missing. There are no playwrights, no books, everything is self-made and self-constructed… I would like to express a great, huge respect to the theater ‘HaNoder’, which proved to overcome all these difficulties and problems and to perform the premiere of Sholem-Aleichem’s ‘The Big Prize’ [Dos groyse gevins] on September 30, and even on a stage, with costumes, with wigs and musical accompaniment – theater in the full sense of the word. And how did they do it? They wrote down the text from memory, patched it together with blanket cutters, borrowed all the stage equipment from workshops and offices, all by themselves, with the support of the actors. At the same time, a whole month was spent rehearsing 4 to 5 hours a day. All this can be achieved with work.”

Undzer Lebn, November 22, 1946

As part of the Berlin Blockade, the U.S. occupiers evacuated all Jewish DPs from the city. Some of them decided to stay in Berlin.