Within a few months, the self-administered Jewish DP camps developed into small towns with schooling, vocational training and cultural, political, sporting and artistic activities.

Nathan Rubinstein (r.) with a group of Jewish DPs in Berlin, 1945–1948 © United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Rita Lifschitz Rubinstein, 61434

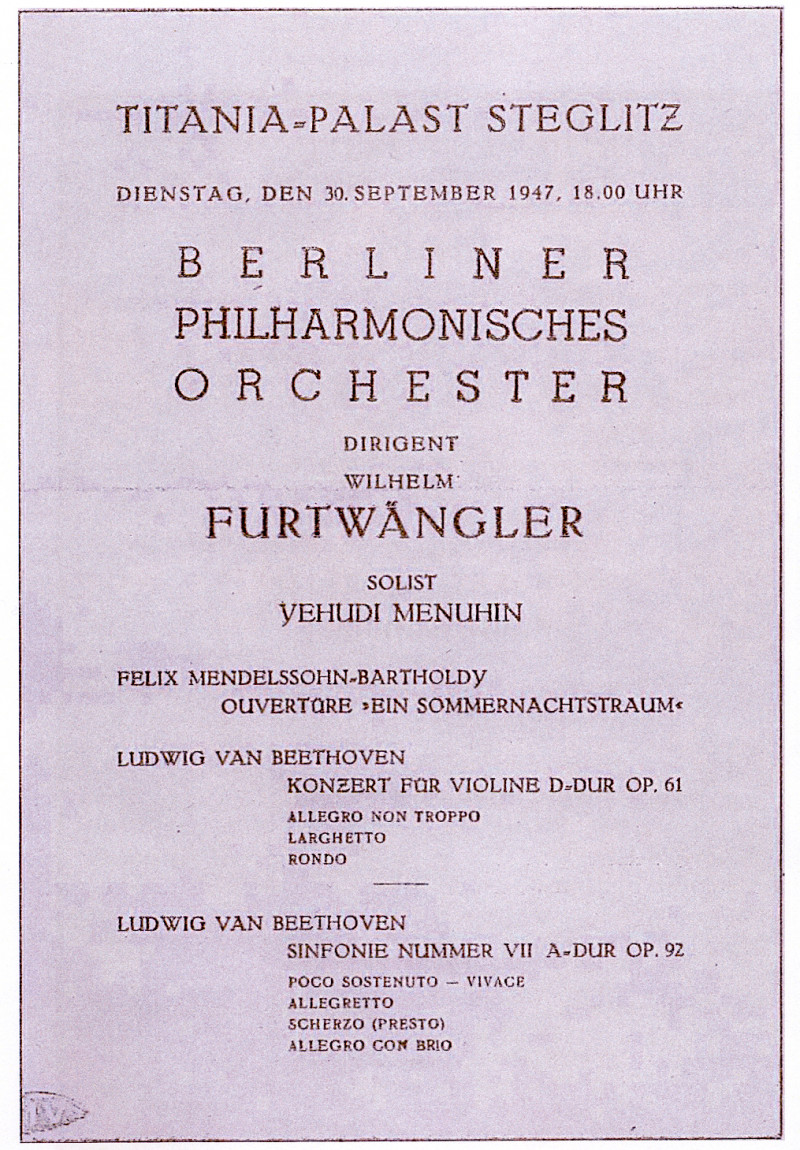

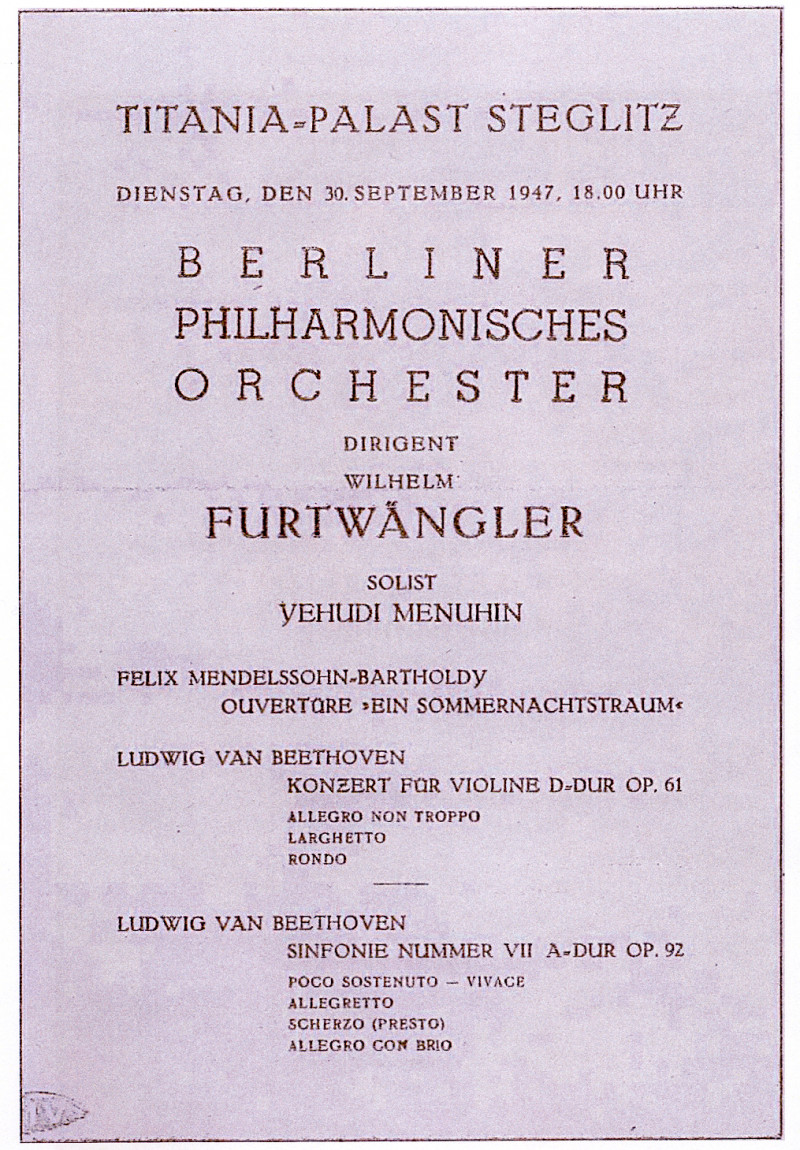

Poster for the Concert by Yehudi Menuhin in Titania-Palast, September 1947

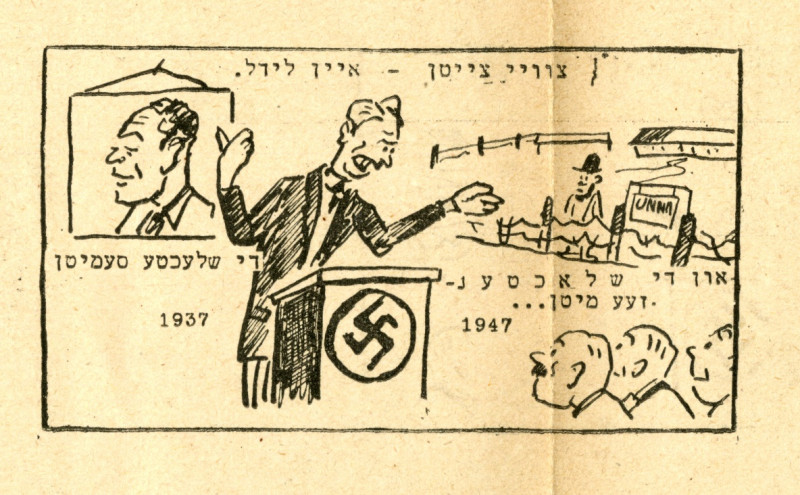

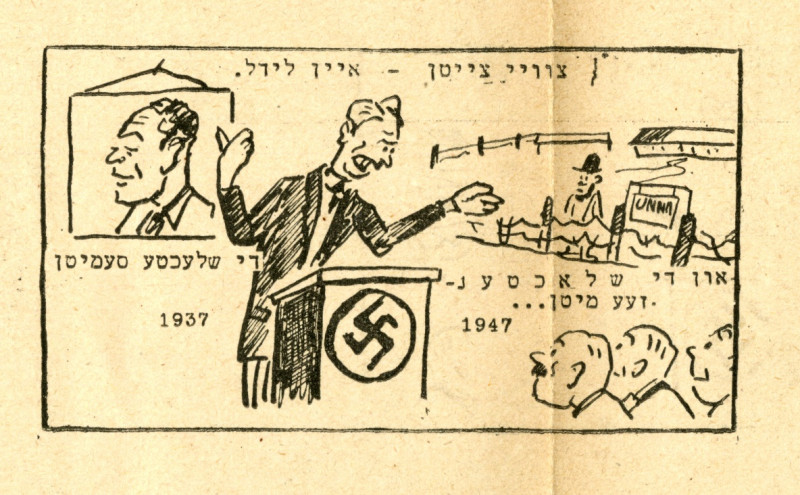

Cartoon from Undzer Lebn, 9. Mai 1947

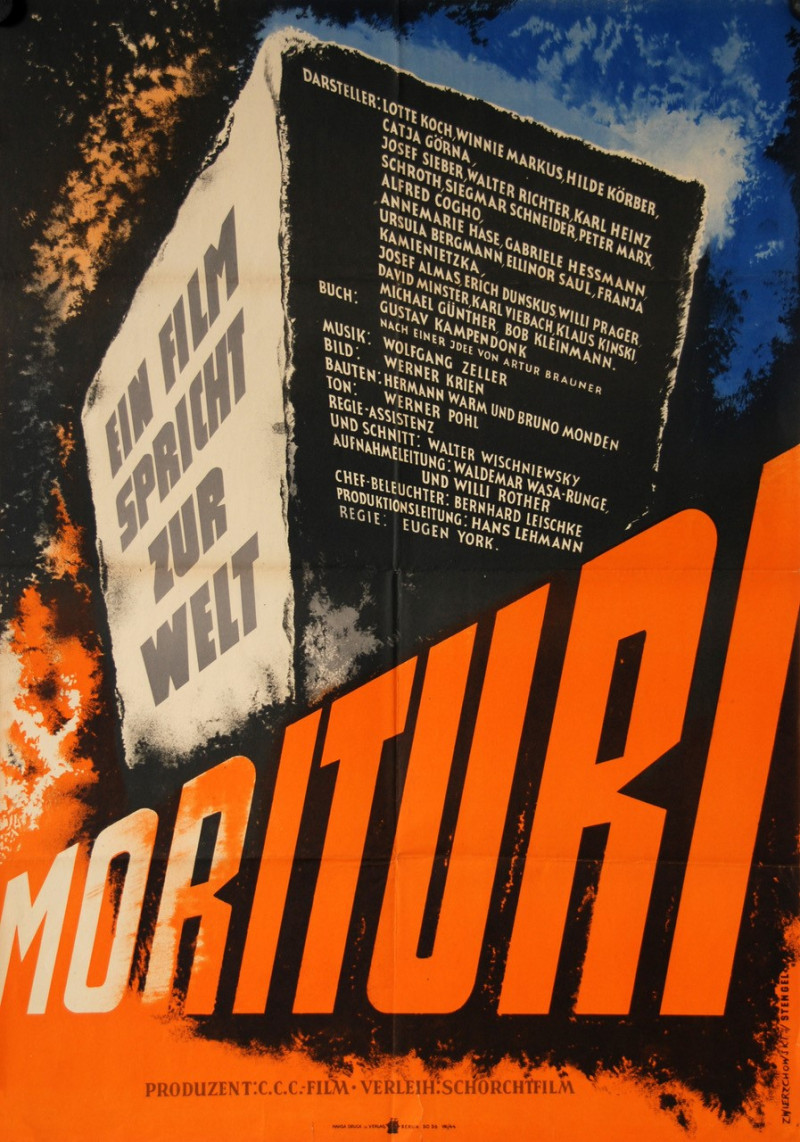

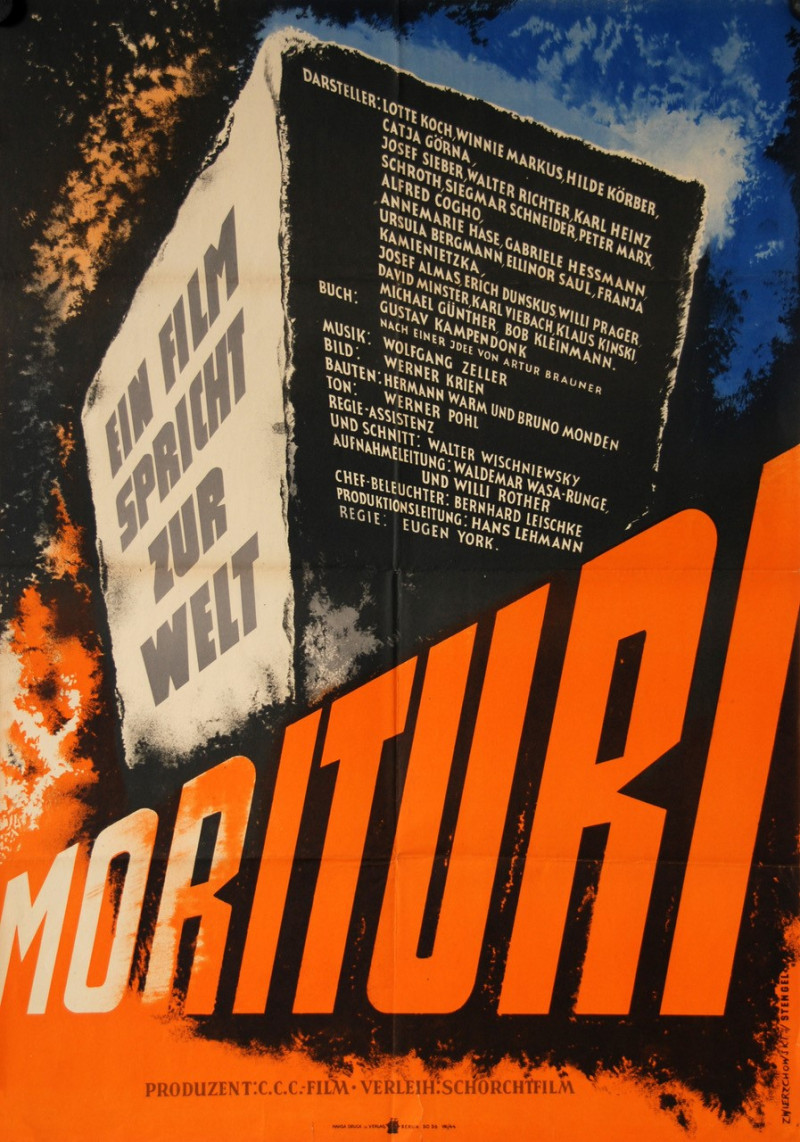

Morituri Film Poster, 1948 © CCC Filmkunst GmbH

Five Jewish DPs waiting for a train at Berlin-Wannsee station, 1946–1948 © United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Lucy Gliklich Breitbart, 04058

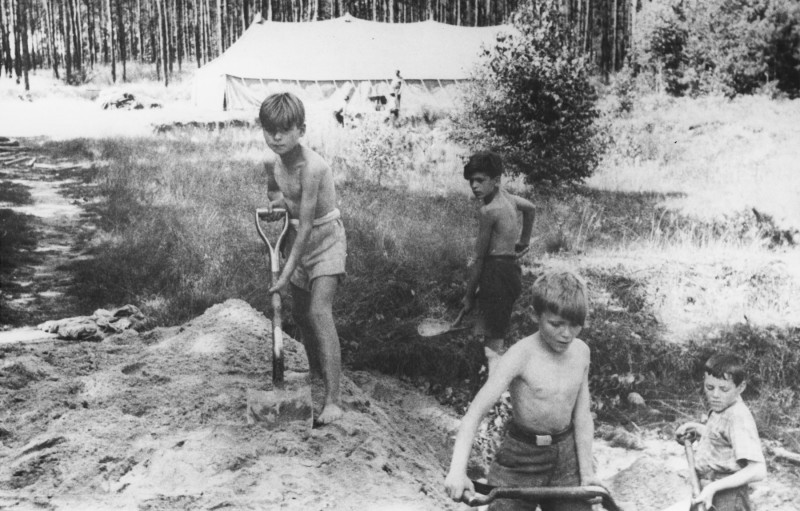

Summer camp for Jewish DP children in Grunewald © United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Mayer & Rachel Abramowitz, 48790

“Among the children, the excursions in Berlin are particularly successful. On ‘UNRRA’ trucks, they go to a different part of the city each time and they look at the surroundings which so recently caused so much horror with childish interest. This is the symbol of our time: Jewish children, rescued from ghettos and concentration camps – at the Brandenburg Gate!”

Undzer Lebn, AUGUST 2, 1946

Most of the Jewish DPs regarded Berlin as “cursed German soil.” The DP camps offered a shelter in which Jewish life could take place largely shielded from the Berlin environment. However, interactions with Jewish and non-Jewish Berliners and Allied soldiers were commonplace. DPs studied at the Technical University, attended Berlin’s theaters and cinemas, and dealt on the black-market trade like the rest of the population. Some Jewish DPs sought lodgings in the city.

“People shout that it‘s hard to find an apartment in devastated Warsaw – a piece of cake. It is hard to get an apartment in Schlachtensee! […] A large number of camp apartments are locked. Their residents live in the city.”

Undzer Lebn, March 18, 1948

These encounters were by no means conflict-free: questions of guilt, reparations, and remembrance shaped internal Jewish disputes and contact between Jewish and non-Jewish Germans. The wide-spread conviction in Germany that Germans were not perpetrators but victims puzzled Jewish DPs. Relationships with non-Jewish Berliners, which were not uncommon, were treated with contempt by DPs and were sometimes even punished by camp courts.

“Chronicle of things that must not become chronic: […] The Polish Jew Levin Antek, who lives in Block 13 Room 8, went out one night to a pub to celebrate with an acquaintance, the German Erika of Crap. He drank like a hero. After all, he is Antek, he is someone! The next morning, like a madman, he looked in vain for his coat, his money! The German, his Verena was missing. The only thing she left him is – a venereal disease …”

Undzer Lebn, December 27, 1946

The case of the American-Jewish violinist Yehudi Menuhin in September 1947 exemplifies the DPs’ internal controversy about how to deal with non-Jewish Germans: after a concert at Titania-Palast in September 1947, conducted by Wilhelm Furtwängler, Menuhin gave a solo performance at the DP camp in Mariendorf. However, hardly anyone came to see him. Upon his inquiry, he received a letter of protest from Elijahu Jones, the editor of the newspaper Undzer Lebn. Jones gave two reasons for the protest: first, conductor Furtwängler‘s involvement in the National Socialist regime was controversial. Second, the concert in Titania-Palast had been organized for the benefit of German non-Jewish children. Menuhin asked for a hearing in the DP camp. There, Jones explained to him in Yiddish:

“Mr. Menuhin. You and us, we cannot find a common language. Instead of talking to each other, we should imagine walking together through the streets of Berlin. When you, the artist, see the ruins, you will say, ‘What a pity that so much beauty was destroyed.’ When we, who lost our families, see the same ruins, we will say, ‘What a pity that so much was left standing.’”

The film Morituri (1947/48) was the second production of the Central Cinema Company (CCC), which had been founded a year prior by Artur Brauner, a Jewish DP from Poland. The film was first shown in Berlin in November 1948. It is the first film shot on German soil to deal with the Shoah and revolves around a group of people who escaped from a concentration camp and hid in the Polish woods. The film could only be shown briefly in Berlin’s cinemas. German audiences reacted with fierce rejection: some movie theaters had to be renovated after the screening due to vandalism. Despite pecuniary injury, Artur Brauner said he never regretted making the film.

In January 1947, a trial took place in the DP camp “Bialik” in Mariendorf against a Jewish DP. He had bought a ring from a German in front of the Tivoli cinema in Tempelhof. Before the war, the ring had belonged to a woman murdered in Majdanek. Since the defendant knew about the origin of the ring, he was expelled from the Jewish community for “desecrating the dignity of the 6 million victims and for treason against the people.”

“Our readers […] do not even know the meaning of the words DP. Readers, excuse us, in the ‘Berliner Illustrierte’ of June 1 […] can learn what kind of cruelties exactly these DPs are capable of, what a terrible element they are and also what the words DP mean. You shall finally know that DP means Germany’s parasites! Yes, Germany’s parasites! We, the victims of German fascism, of the German army, of the German people, we, where each of us is only a remnant of a whole community, we are therefore, due to the fact that we remained alive, Germany’s parasites!”

Undzer Lebn, July 4, 1947

The economically ruined postwar city of Berlin offered ideal conditions for the development of a lively black-market trade, in which the military of the occupying powers, non-Jewish Berliners and displaced persons were equally involved. The activities of Jewish DPs in the black market reinforced already existing antisemitism. The German majority population saw itself as being treated unfairly since the Jewish DPs received better food supply. Thus, the Eastern European DPs, who were stigmatized as foreigners, were primarily held responsible for the black-market activities. Military reports by U.S. soldiers also contain attributions that testify to deep-rooted antisemitism.

“Significantly, inhabitants of Reinickendorf call the UNRRA camp ‘Shack of Jewels.’ […] They feel very comfortable in Germany, these gentlemen. They want for nothing […] Why doesn‘t the police do the least against these ‘guests’? […] They take advantage of the generosity of the Allied authorities to line their pockets to the detriment of the German population.”

Newspaper Neue Zeit (“New Time”) of the Christian Democratic Union, May 25, 1947

Among the Jewish DPs, the issue was met with outrage. Those in charge did everything in their power to put a stop to black-market activities from their own ranks. For one thing, they were afraid that people might get on the wrong track due to a lack of prospects. Furthermore, they feared that the participation of a few in the black market could discredit the entire DP community.

“The black market exists as it always has; all that has disappeared is the scapegoat onto whom blame could be shifted.”

Jewish newspaper Der Weg after the evacuation of the DP camps, August 6, 1948

Within a few months, the self-administered Jewish DP camps developed into small towns with schooling, vocational training and cultural, political, sporting and artistic activities.