New anti-Semitic violence in Poland forced Jewish survivors who had returned after liberation to flee abroad, including to Berlin.

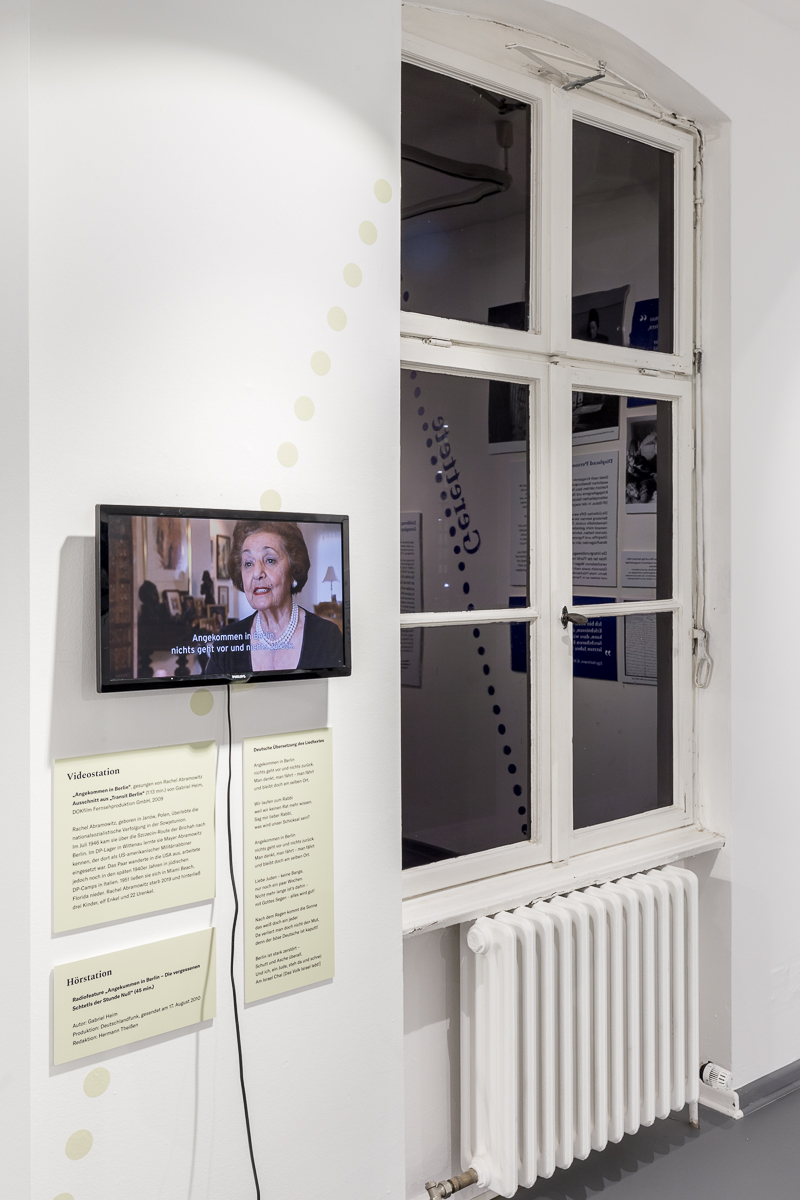

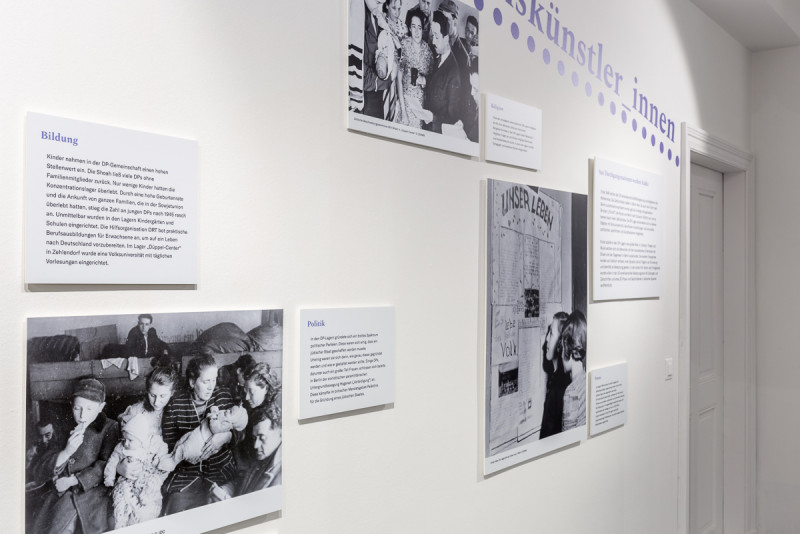

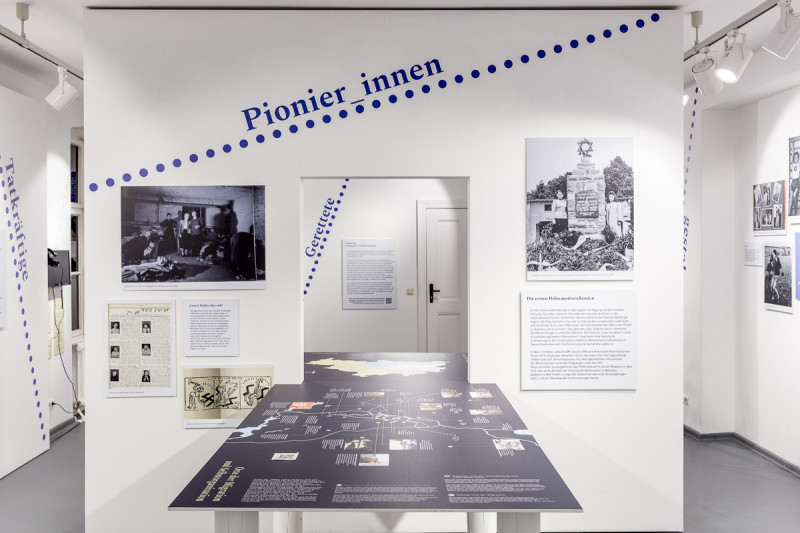

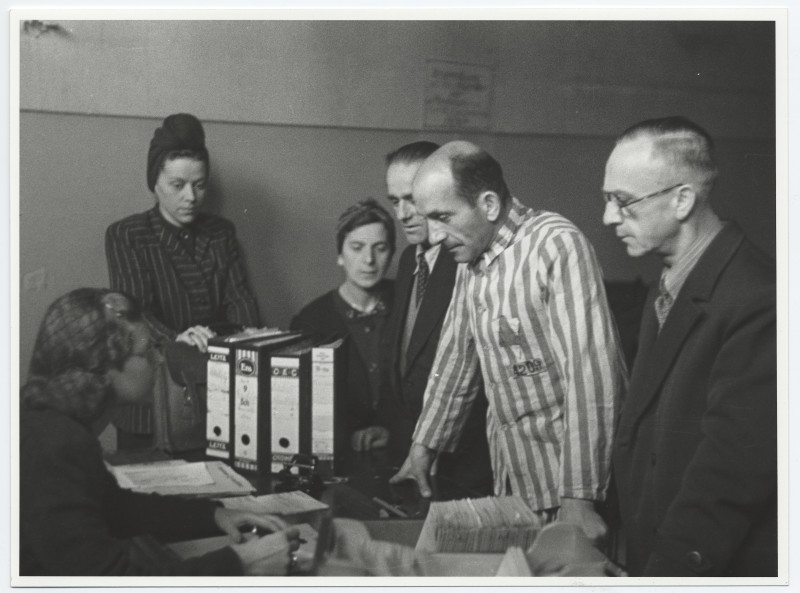

Insight into the exhibition at Tempelhof Museum © Klaus R. Bittl

Insight into the exhibition at Tempelhof Museum © Klaus R. Bittl

Insight into the exhibition at Tempelhof Museum © Klaus R. Bittl

Insight into the exhibition at Tempelhof Museum © Klaus R. Bittl

Insight into the exhibition at Tempelhof Museum © Klaus R. Bittl

Insight into the exhibition at Tempelhof Museum © Klaus R. Bittl

Insight into the exhibition at Tempelhof Museum © Klaus R. Bittl

Insight into the exhibition at Tempelhof Museum © Klaus R. Bittl

Insight into the exhibition at Tempelhof Museum © Klaus R. Bittl

Insight into the exhibition at Tempelhof Museum © Klaus R. Bittl

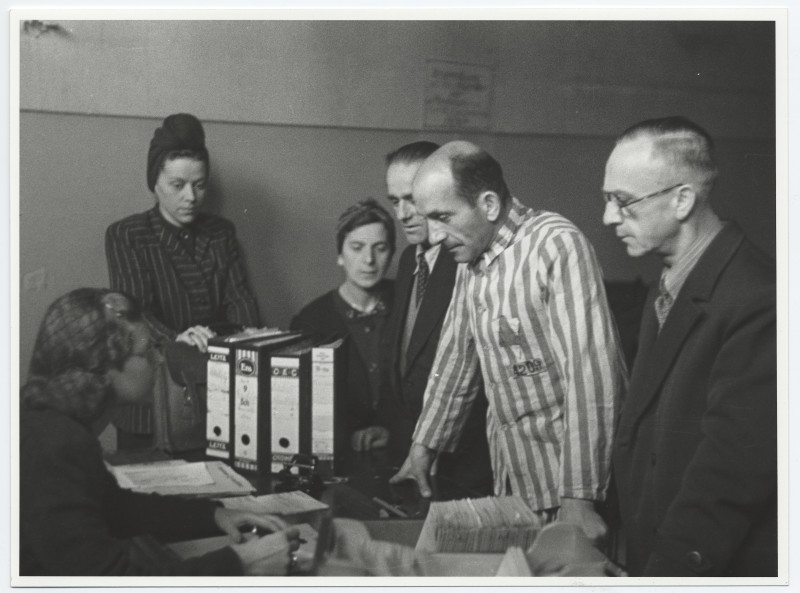

After the end of World War II, Berlin became a place of refuge for millions of refugees and displaced persons (DPs). Several groups of people who had lost their homes through war, enslavement and persecution fell under the DP status.

In addition to former forced laborers, foreign contract workers and prisoners of war, Jewish displaced persons also found themselves in Berlin. They had been liberated from Nazi concentration camps or on death marches or were returning from exile. They called themselves she‘erit hapletah, (Hebrew for “the surviving remnant”, in Yiddish sheyres hapleyte). For most of them, Germany, as the land of the perpetrators, was the last place they wanted to stay.

Three larger transit camps for Jewish DPs were established in the destroyed city. Being housed in a camp again had a retraumatizing effect on many. But within a few months, the camps developed into self-governing small towns within the urban area of Berlin. The camps remained only until 1948, but some residents stayed in the city for the rest of their lives.

The exhibition tells the story of Jewish displaced persons as border-crossers. It sheds light on their everyday life inside and outside the camps, and their shaping of a future after the Shoah. Their presence, whether temporary or permanent, has left its mark on the city. The history of Berlin is one of migration and refuge: without acknowledging the participation of border-crossers, a historiography of Berlin as a city of immigration is impossible.

New anti-Semitic violence in Poland forced Jewish survivors who had returned after liberation to flee abroad, including to Berlin.