New anti-Semitic violence in Poland forced Jewish survivors who had returned after liberation to flee abroad, including to Berlin.

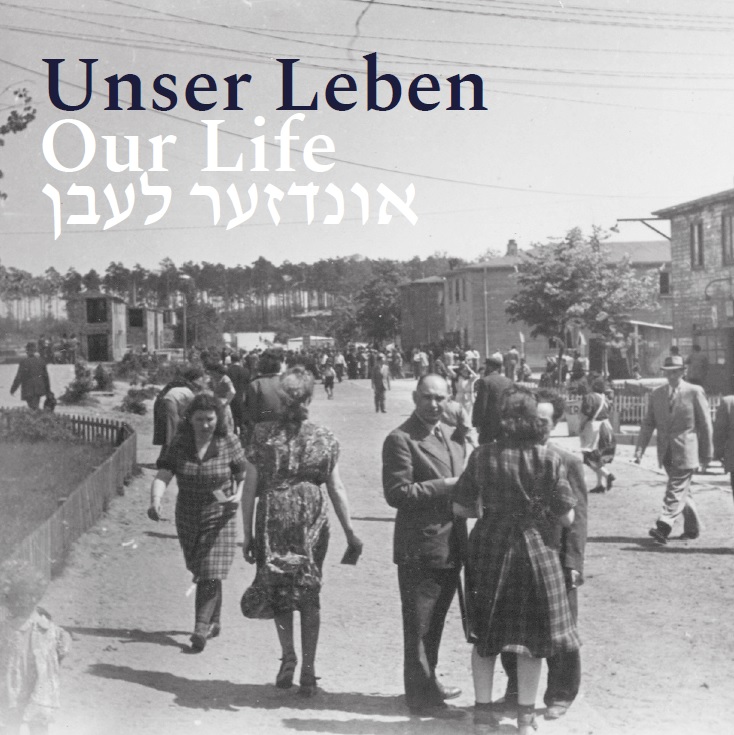

After the end of World War II, Berlin became a place of refuge for Jewish displaced persons (DPs). They called themselves she’erit hapletah, “the surviving remnant.” For most of them, Germany, as the land of perpetrators, was the last place they wanted to stay.

After the end of World War II, Berlin became a place of refuge for Jewish displaced persons (DPs). They called themselves she’erit hapletah, “the surviving remnant.” For most of them, Germany, as the land of perpetrators, was the last place they wanted to stay.

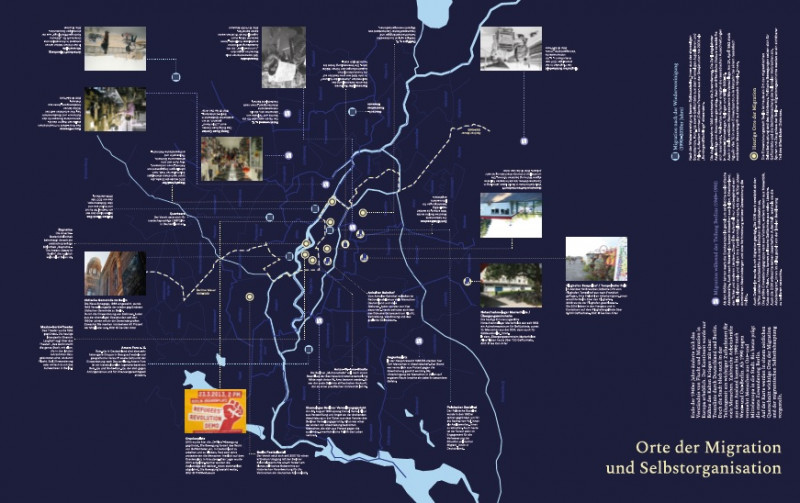

In Mariendorf, Zehlendorf und Reinickendorf, camps were established in which Jewish DPs often lived for several years. The exhibition tells of their everyday life inside and outside the DP camps and their hopes for a future after the Shoah. At the same time, it takes a transhistorical look at the immigration city of Berlin, which remains a place of migration and refuge for many people to this day.

New anti-Semitic violence in Poland forced Jewish survivors who had returned after liberation to flee abroad, including to Berlin.

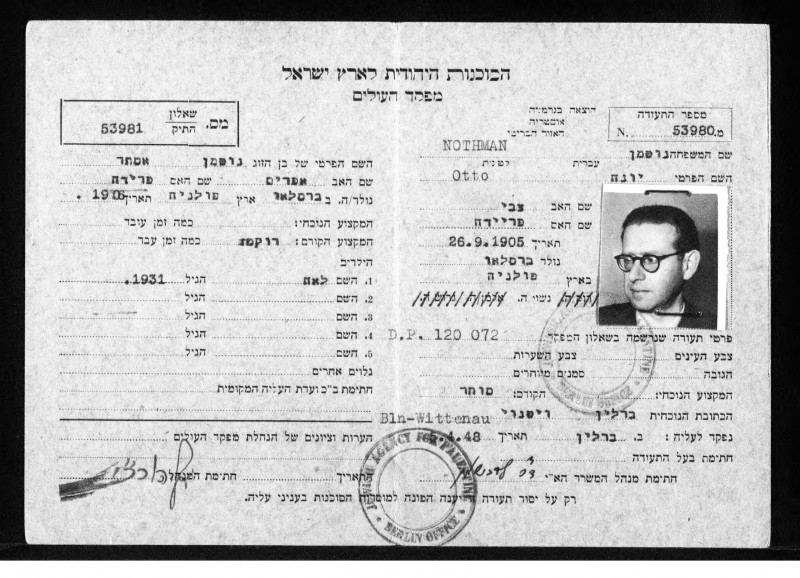

At the request of Jewish DPs, the U.S. military administration established self-governing DP camps for Jewish survivors in its occupation zone.

Encounters between DPs and the rest of the Berlin population were part of everyday life, and dominated by questions of guilt, reparations, and remembrance.

Within a few months, the self-administered Jewish DP camps developed into small towns with schooling, vocational training and cultural, political, sporting and artistic activities.

As part of the Berlin Blockade, the U.S. occupiers evacuated all Jewish DPs from the city. Some of them decided to stay in Berlin.

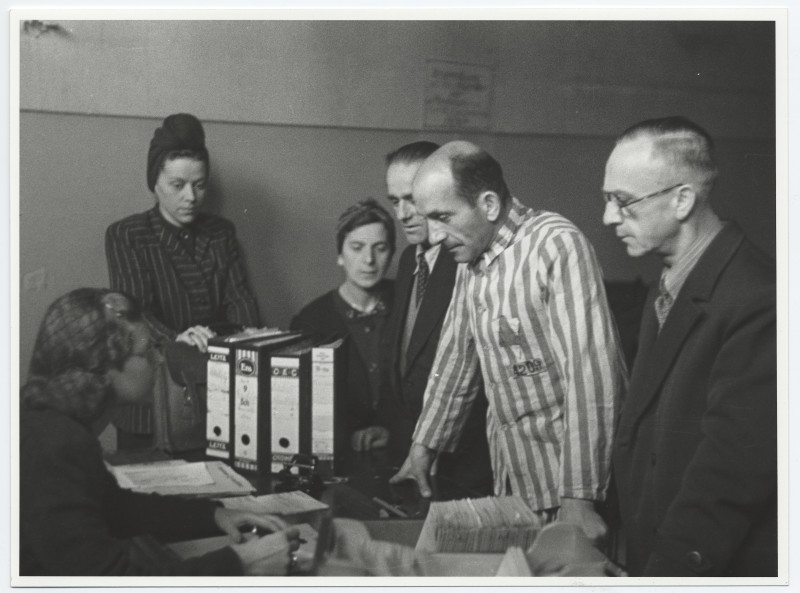

In their confrontation with their own persecution and the losses they experienced, Jewish survivors in Europe were the first to research Nazi crimes.

Today, the city of Berlin is a place of immigrant self-assertion and activism. Political movements advocate for refugees and the visualization of colonial crimes.