Dear Günther –

Just now I received your postcard and answer you to calm you down as soon as possible. We’re still in Paris, Mutt and I, and I’ll do everything I can to stay. Unfortunately, Monsieur had to go to a camp where all the other German nationals were gathered, without any distinction. We hope that this will not be too much of a stretch. Benji, for example, is also there – I do not even know where – and for him it will be a small catastrophe. The population is wonderful, seriously, and understands our situation very well. Nothing has yet been decided about us women; but it is of course very possible that we will also be “gathered.” This is no cause for concern, because everything here is done in a very humane way. I am writing this to you only so that you will not be worried when you hear nothing more.

I have just received a letter from Henri – you see, [everything] is fine.

Mutt is fine and she’s helping me a lot. I see very few people, but Channan comes by almost every day. He’s Polish and will leave in one of the next weeks. We very much regret that there is no Jewish legion. Well – the future will tell.

Will you be able to read this? – I doubt it. But postcards are faster. And I wanted to use what little space I had.

All my love.

H.

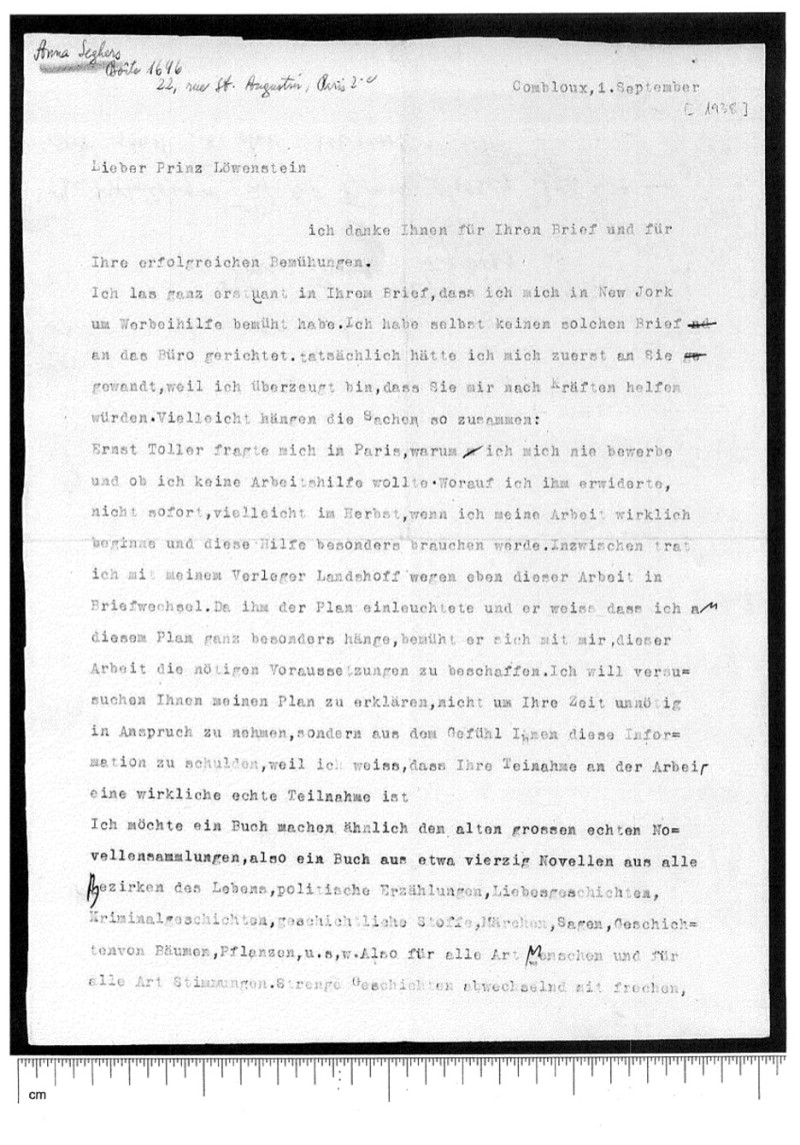

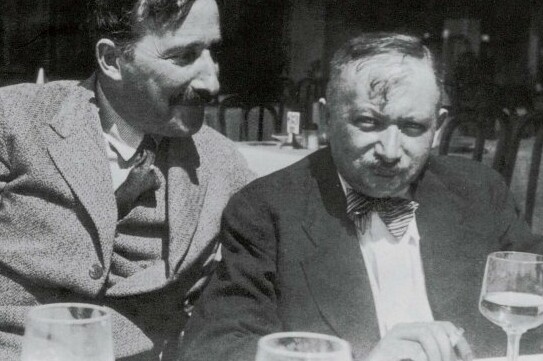

From 1929 to 1937 Hannah Arendt (1906-1975) was married to the German-Austrian philosopher, poet and writer Günther Anders (bourgeois Günther Siegmund Stern, 1902-1992). Anders also fled to Paris in 1933, where Arendt would follow him shortly afterwards. In 1937 they broke up due to the economic and emotional hardship they faced as refugees in the Quartier Latin. But even after the divorce, they remained friends. At the time of the letter Arendt was already married to Heinrich Blücher, whom she had already met before the divorce from Anders.

The letter was written in the uncertain phase before the French authorities instructed the majority of foreigners of German descent via the press to report for internment in early May 1940. Arendt’s letter is testimony to the network and solidarity that had developed in the refugee community in Paris. Arendt was interned with many other women for a week on the grounds of the Buffalo Stadium. Soon after, she was interned as an “enemy alien” for four weeks in the southern French camp of Gurs. Together with Heinrich Blücher she managed to escape via Lisbon to New York. Günther Anders was already waiting for them there.

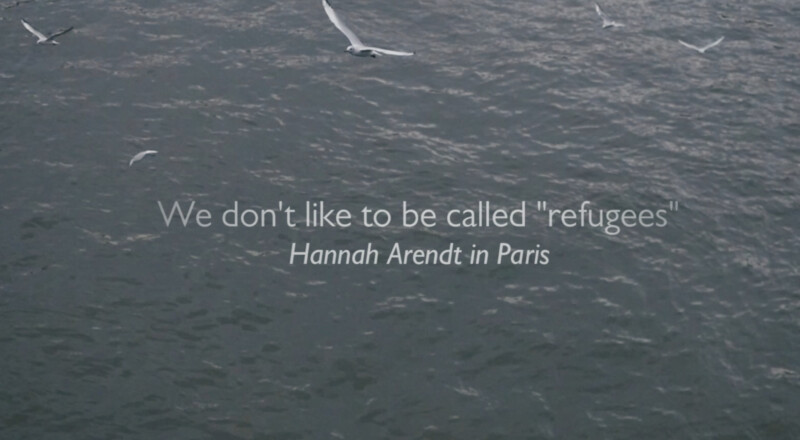

Hannah Arendt (1906-1975) was a Jewish German-American political theorist and writer.

After being detained by the Gestapo for several days in 1933, she fled to France and worked there, among other things, in Zionist organizations that helped Jews to escape. In 1937 she was deprived of German citizenship, which made her a stateless person for almost 14 years. After she was imprisoned for a few weeks in the French internment camp Gurs, she managed to escape from there as well. In 1941 Arendt came to the USA, where she spent the rest of her life and was granted US citizenship in 1951. In her first years in New York she worked as a publicist, editor and contributor to several Jewish magazines (including “Der Aufbau”) and organizations (including the Commission on Jewish Cultural Reconstruction). Under the impression of the experience of flight and arrival that she and other European Jews had had, she also wrote the essay “We Refugees” in the Menorah Journal in 1943. From 1953 to 1967 Arendt taught as a professor at Brooklyn College in New York, at the University of Chicago and at the New School for Social Research in New York.

Arendt, Hannah, 1942; Anders, Günther: Schreib doch mal hard facts über dich. Briefe 1939 bis 1975, Texte und Dokumente. Munich 2016. P.12.