An Stefan Zweig

47, Rue Jacob

Hotel Jacob

Paris IV.

[Mitte Februar 1933]

Verehrter lieber Freund,

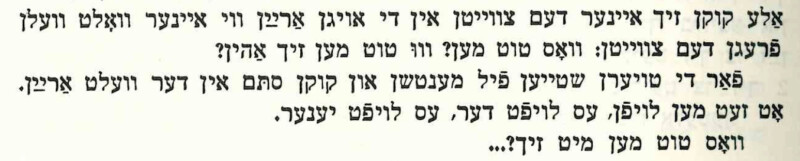

[…] Inzwischen wird es Ihnen klar sein, daß wir großen Katastrophen zutreiben. Abgesehen von den privaten – unsere literarische und materielle Existenz ist ja vernichtet – führt das Ganze zum neuen Krieg. Ich gebe keinen Heller mehr für unser Leben. Es ist gelungen, die Barbarei regieren zu lassen. Machen Sie Sich keine Illusionen. Die Hölle regiert.

Herzlichst Ihr alter

Joseph Roth

To Stefan Zweig

47 rue Jacob

Hotel Jacob, Paris 6e

[mid-February 1933]

Dear esteemed friend,

[…] It will have become clear to you now that we are heading for a great catastrophe. Quite apart from our personal situations—our literary and material existence has been wrecked—we are headed for a new war. I wouldn’t give a heller for our prospects.

Warmly your old,

Joseph Roth

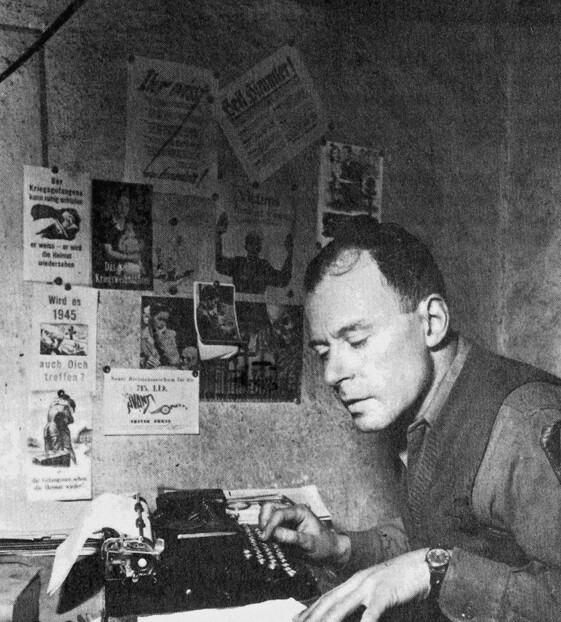

Joseph Roth is considered one of the most famous journalists of the 1920s, a precise chronicler, successful novelist and committed opponent of National Socialism. His literary and journalistic work consists of newspaper articles, glosses, travel reports, feature articles, novels and short stories.

Roth grew up in Brody in eastern Galicia, studied in Lemberg and Vienna, was a soldier in World War I and experienced the collapse of the Habsburg Empire – his home country. Nostalgia for this multi-ethnic empire haunted the rest of his life and many of his novels are dedicated to the loss of homeland and the experience of uprooting. From 1919 he worked as a journalist for various Viennese, Berlin and Prague newspapers and magazines as well as for the Frankfurter Zeitung.

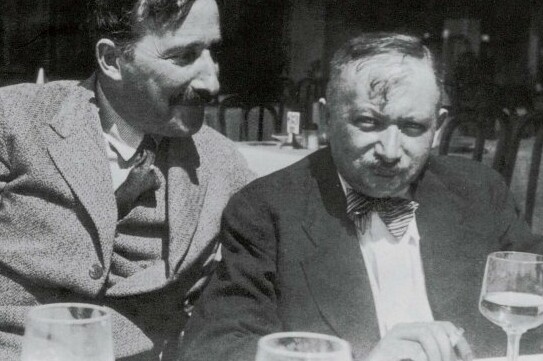

As a Jew, Roth was no longer allowed to publish there after 1933. He left Germany for good and continued his commitment against the National Socialism in his Parisian exile. He was involved in aiding refugees, for example for Entre’ Aide Autrichienne, and cultivated close ties with fellow refugees, including Stefan Zweig (1881-1942), to whom the cited letter was addressed, Ernst Toller (1893-1939), Egon Erwin Kisch (1885-1948), Soma Morgenstern (1890-1976) and Irmgard Keun (1905-1982). Most of the time he lived in hotels in Paris. Café Le Tournon became Roth’s main place of residence, where he gathered his “entourage” around him. Suffering from a severe alcohol addiction, his last years were clearly impacted by the political circumstances and the experiences of refugeedom. He did not live to see the Second World War; he died on May 27, 1939, in the Hôpital Necker, a hospital for the poor in Paris.

Deeply influenced by the experiences of the First World War and a keen observer of the rising German fascism, in this letter to his friend Stefan Zweig, he predicted a new war as early as February 1933. Of course he could not foresee the Holocaust in all its dimensions.

Joseph Roth to Stefan Zweig, mid-February 1933, Paris

German Original: Joseph Roth, 1970: Briefe 1911–1939. ed. Hermann Kesten. Köln: Kiepenheuer & Witsch. P. 249.

English Translation: Roth, Joseph, 2012: A Life in Letters. Translated and edited by Michael Hofmann. New York: W. W. Norton & Co. E-Book. 443.