Ingredients

1 kg of ground beef

250 grams of flour

1 white onion

A pinch of black pepper

1 tablespoon of cumin or curry

1 teaspoon of salt

1 liter of oil for frying

Water as necessary

Parsley (to your liking)

Preparation (for 4 people)

The dough:

Mix and knead the flour with water and salt. Stretch out the dough in the form of a disk as if making a pizza, as thin as possible. Cut through the disk with two crossing diagonal lines to obtain four triangular parts.

The filling:

In a frying pan, cook the ground beef together with the chopped onion, pepper and salt until the meat is nice and brown. Then add cumin or curry and the parsley just a few minutes before taking it off the burner.

Stir a tablespoon of flour in a glass of water to be used as glue. It should be neither dense nor liquid. Create cones with the triangular dough and fill them with some of the spiced ground beef, gluing the corners with the flour mixture. Fry the sambus in very hot vegetable oil, turning them over every few minutes. They will be ready once they reach a golden color (in about 4 minutes).

I remember very well the first time I cooked.

I was fifteen years old. My mother didn’t want me near the stove or doing any housekeeping. She used to cuddle me and was always afraid of the fire from the burners. But I really loved cooking, so one day while my mother was out and I was alone in the house, I started cooking a meal. When my family returned, everything was ready.

My family is very large, six sisters and three brothers. I studied in a private English school because, since 1990, public schools have not been accessible in Somalia. The war brought destruction and that signaled the end of our life. We could not go out and could not go to school. My brother and his daughter died under the bombs. I remember the desperation of a close friend who returned home to find a pile of rubble under which her entire family lost its life.

We could not stay in Somalia. Those who escaped death fled to other countries. I was terrified and wanted to leave. My mother didn’t want me to go, my brother was the one who helped me. I left with some of his friends and my cousin. Everyone was much older than me. I was only seventeen.

I crossed the desert in a 4X4 along with fifty other people. The journey was terrible; it felt almost worse than being under the bombs. After three days, we no longer had food or water. During those months, I often regretted having left, but thankfully I survived.

At the Libyan border, we were kidnapped and taken to a home where we couldn’t leave without giving our captors all our money. I told them I didn’t have any money and they became angry with me. They could do anything to a woman. I stayed in Libya for a month waiting for my journey to Europe, the dream of all of us, a place where we could have freedom, peace, wealth…

In May 2008, I got on a boat for the first time along with sixty people. There was so much confusion, everyone was screaming as if they had gone mad. We were all shocked not to see a safe boat as expected. Instead, it was a small dinghy, too small for all of us. In the end, we went anyway. On the second day of our journey, the dinghy was already deflating and sinking but thank God we were rescued by a large ship that was nearby and which took us to Tunisia. From there we reached Tripoli by foot. During our journey back to Libya we were afraid to be arrested, we knew it happened to some of us. We cannot travel freely, we do not have a proper visa and we live in constant fear even when we haven’t done anything wrong.

After three weeks we were told that we could board another boat to Europe – no one ever knows how long it takes for that to happen. You have to wait, wait, wait and hope that in the meantime you will not be kidnapped in the streets, raped, or locked up. Like the previous boat, this one was also very precarious, and this time there were seven children and several pregnant women among the passengers. On the second day of our journey, the boat literally split in half. We all started screaming, crying and praying, but God is mighty, and I escaped death this time, too. I remember the rescue team arriving immediately and we were taken to Lampedusa. I still remember the warmth of those who came to help us at the port.

After few days I was taken to Bari to a camp where there were almost two thousand people. They put me in a container along with two Somali girls. I stayed in that camp for eight months waiting for a hearing with the commission in order to receive my permit to stay. Those eight months were brutal, time seemed to never pass. But then I met my husband, Qader. Actually, we knew each other from when we were in Somalia. He used to come play soccer with my brothers in the neighborhood, but we were children then. When we saw each other again in Bari we started to date. He was nice to me, we were both in a precarious situation. He had not yet had his hearing with the commission.

When I left the camp with a permit, I didn’t have a place to go. I was along, in the streets, and so I tried my luck and travelled to Switzerland. Once there, I presented an application for asylum and after three months the police told me I couldn’t stay. I was taken to a special jail where all the undocumented foreigners were detained. After a few days, handcuffed, they took me to the airport to board a flight to Rome’s Fiumicino airport. Handcuffed… I felt so ashamed! I am not a criminal. I am a young woman looking for peace and tranquility. That is how I returned to Italy.

I was sent to a welcome center in Sicily where I worked as a housemaid for an Italian family. The situation was fine but very precarious. In the meantime, Qader continued to call me and one day he asked me to marry him.

We immediately called our families and they organized a proxy marriage. On the phone, my mother asked me if I was happy with Qader and I replied yes. She cried for my happiness. She had been worried about me, young and alone on this journey. I had just turned eighteen. On the phone with the qadi from Mogadishu my husband and I exchanged our vows and our families celebrated together for us in Mogadishu. In Somalia, a wedding is a very special celebration. Those who are wealthy can offer a camel. Our families could offer only four cows and four lambs. Qader and I could not celebrate as we would have liked, and I missed not having all my family and friends on that special occasion. I missed the shaash saar, the scarves that women give as a gift to a bride after the wedding. Sambus are prepared for this occasion too, along with many sweets while singing and laughing among women. But that’s life…

Now I have two children, a girl and a boy. My mother has only met them via photographs, and I am not sure when and if they will ever be able to meet in person. My first child is a girl and she is vivacious and intelligent. I speak to her in Somali and she understands everything though she always replies in Italian. History can be strange. My grandfather spoke Italian and now my daughter speaks it too, but for the opposite reasons. She is beautiful and I would never do to her what they have done to me when I was just a bit older…

I still remember it so vividly. I was at home with my mother waiting for Nadifa, an older woman who “sewed girls.” They laid me down and told me that, from that day on, I would become a clean woman and then all I remember was the pain and the fear of dying. I was “sewed” without anesthesia and for two weeks I was very sick in bed. I was afraid to even go the bathroom. I have escaped death so many times: first as a child, then under the bombs, and twice on the sea.

I will never put my daughter through that experience. Infibulation is a tribal practice that has nothing to do with Islam. I remember that, right before I left Somalia, this was a topic of discussion and even imams used to say that Islam did not mandate infibulation, a tradition that does not need to be respected. Therefore, for Islam, doing so is not a sin. I remember my mother’s face when she apologized to me for having put me through it. Even she had started to view it as dangerous and would be happy if it were no longer practiced. I will never do such a thing to my daughter because I love her too much.

I miss my mother very much. I hear her voice while I make sambus for my family. I see her joking, and immediately I become very sad and revisit everything I went through. Often, I cook and eat by myself and cry. In Somalia, it is inconceivable that a person eats by herself. We always eat together, three times a day, for breakfast, lunch and dinner. And we also talk a lot, we tell each other about our day and sometimes we argue.

I call my mother every day. Usually, she laughs, blesses me and tells me not to be worried. But then there are days when she cannot hold her tears because she is afraid, she will never see me again. I reassure her and tell her that she will see her grandchildren soon. I make sure to sound cheerful, but as soon as I hang up…

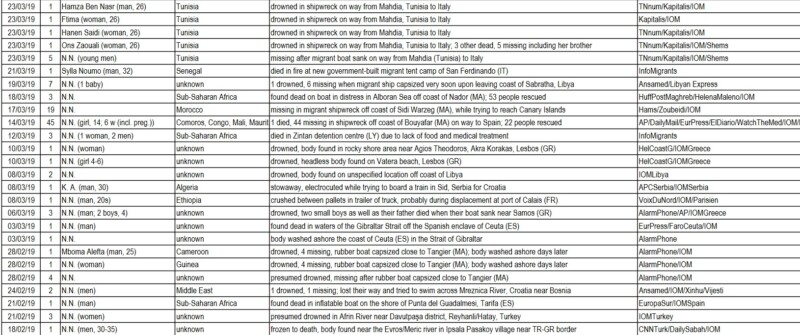

In her report, Hamdi tells of sambus, a dish from her homeland Somalia, the preparation of which she learned from her mother and which still reminds her of her childhood. She shares the recipe for sambus and her story of escaping from war-torn Somalia via Libya and the Mediterranean Sea to Italy. In the reception camp in Bari she meets her husband Qader, with whom she founds a family. Today they live with their daughter and son in Italy.

Hamdi maintains close contact with her mother in Somalia; she tells how much she misses her family. Her mother only knows her grandchildren through photos.

Trigger warning: Hamdi shares her story of female genital mutilation.

Hamdi, Somalia: Sambus, in: Bhakti Shringarpure (ed. et al.), 2019: Mediterranean. Migrant Crossing. Storrs, CT: Warscapes Magazine, pp. 16-19.

Translated to English by Veruska Cantelli. From: Cum-panis, 2014: Storie di fuga, identità e memorie, in quattro ricette a cura die Associazione Culturale Multietnica „La Kasbah Onlus“, die Enza Papa e Francesco Mollo Edizione Erranti.

Reposted from Mediterranean. Migrant Crossings with the kind permission of Bhakti Shringarpure, founder and editor in chief of Warscapes.

For a review of Mediterranean. Migrant Crossing see here.