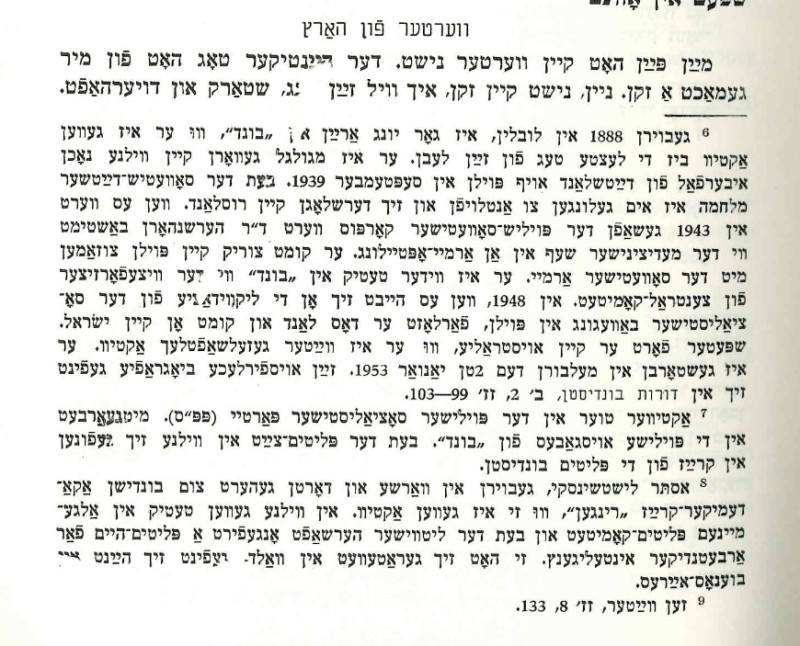

Mass Deportations of Polish Jews from Germany in 1938 and Their Consequences

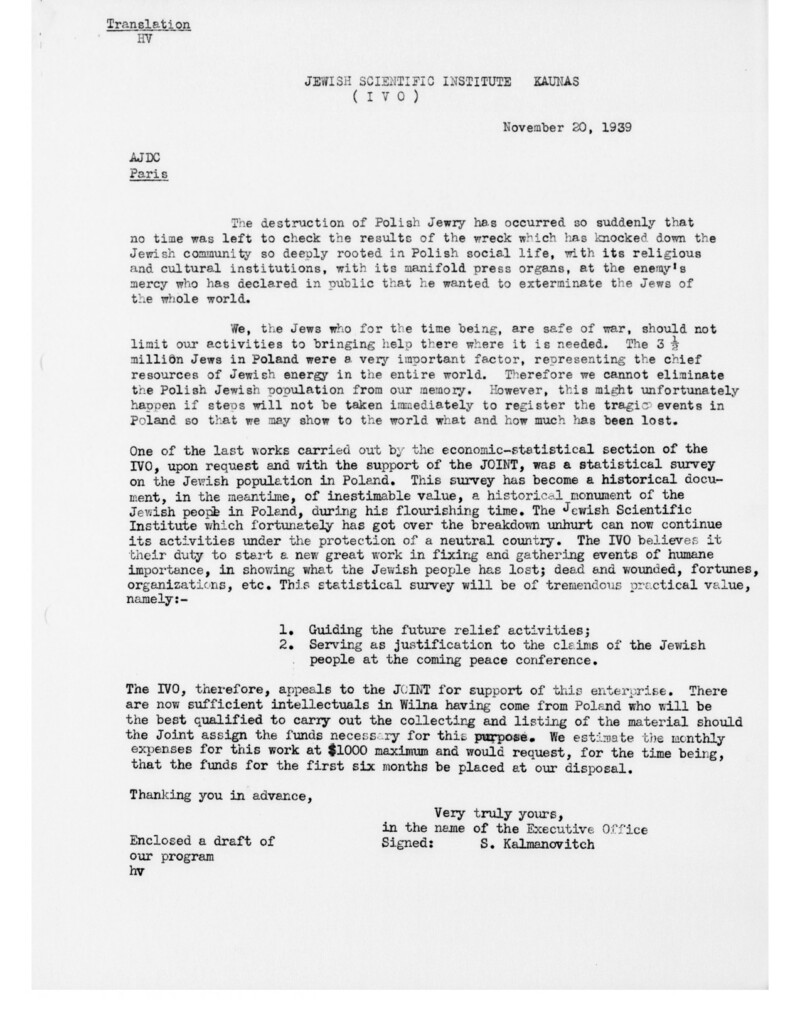

At the end of October 1938, in what would set the paradigm for the following anti-Jewish measures by the Nazi State, about 18,000 of the Polish Jews living in Germany were deported as part of the so-called “Poland action.” Many of them became stateless and were caught for months in a no man’s land on the border between the German Reich and Poland. Among them were also the parents of Herschel Grynszpan, a Polish-Jewish refugee living in Paris, who on November 7 shot the Ambassador of the German Reich to France, Ernst vom Rath in a retaliation.

The murder of vom Rath provided the Nazi state with a welcome excuse for the November pogroms, which took place in the night from November 9th to November 10th. In the course of the following day the state organized a series of violent riots against the Jewish population, mostly led by the SS and SA. After the pogroms, deportations of Jewish men to concentration camps took place. There, the prisoners were given a choice: if they committed themselves to emigration as soon as possible, they were released. In December 1938, shortly after these incidents, Goering announced to the Gauleiters, High Presidents and Governors, what Hitler had instructed:

“At the forefront of all our considerations and measures is the objective to refer the Jews to be deported abroad as quickly and as effectively as possible, to forcefully emigrate them, and to take away everything that prevents their emigration.”

In addition to these specific measures of forced displacement, the Nazi regime implemented further laws and decrees that made life so difficult for Jews living in the territory of the German Reich in order to get them to flee. In 1935, the Nuremberg laws passed that defined who was Jewish according to a racist ideology. This state-implemented anti-Semitism led to the fact that people defined as Jewish were no longer allowed to work, live and own as before.

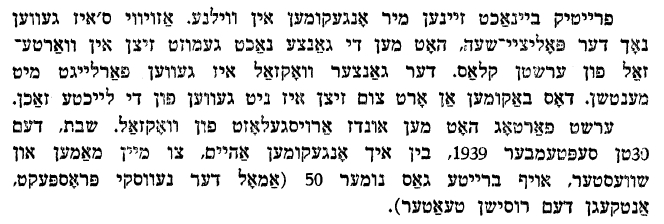

Emigration with Obstacles

The Nazi state’s expulsion policy resulted in an increasing number of Jews seeing themselves in a position of being forced to emigrate. The German government pressed for this and made a profit from emigration by preventing private capital from being transferred from Germany abroad and withholding up to 70 percent of the capital. These restrictions tightened over time. In 1938, the so-called flight tax forced the refugees to surrender a quarter of their assets in addition to emigration. In April 1938, all Jews in Germany had to give detailed information about their capital. The total of the amounts – about seven billion RM – was meant to flow into the “German economy” and thus into armament.

In November 1938, the Reich’s Central Office for Jewish Emigration was founded in Berlin – analogous to the central office for Jewish emigration in Vienna – and was supposed to force destitute Jews in particular to leave Germany. At the same time, the institution expedited the economic looting of the emigrants.

There were three organizations that informed refugees about emigration. Financial obstacles made it impossible for many people to flee – not least because target countries also required equity capital for entry. International Jewish organizations like the Jewish Agency mediated between the German and foreign governments.

About three fifths of the Jews in Germany succeeded in emigrating. Most of them went to the USA, followed by the then British mandate of Palestine, Great Britain (about a fifth of them children who entered without parents) and South American countries. For many, the last possible option remained Shanghai until 1941, which was an escape destination for which no entry visa was required.

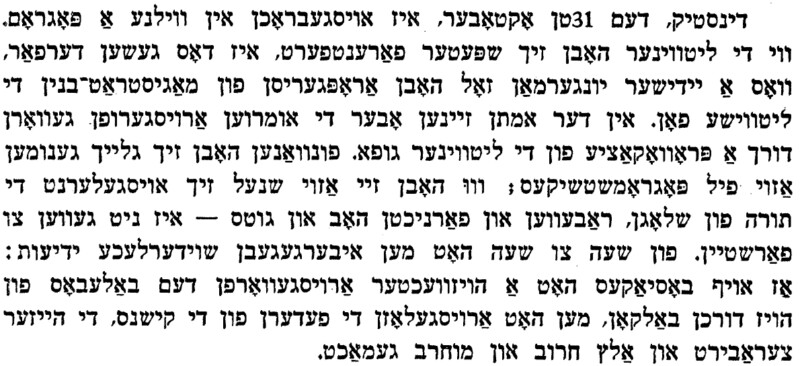

The Madagascar Plan

The National Socialist government’s plan to deport about four million Jews from Europe to the former French colony of Madagascar was negotiated in Berlin until the summer of 1941. However, the seriousness of this plan remains debated until today and is primarily considered a government sham. Hannah Arendt also wrote in 1963 that the Madagascar Plan was to “serve from the start as a cover under which the preparation for the physical extermination of Western European Judaism could be driven forward.” The annihilation of the Polish Jews had also already been “something agreed upon.”

Expatriation – Travel Ban – Systematic Deportations

As early as 1933, the Reichsanzeiger published the names of the people from whom the German citizenship had been withdrawn. The first expatriates were those Jews who had immigrated from Eastern Europe. With the help of the laws “on the revocation of naturalizations and the withdrawal of German citizenship” as well as “the confiscation of the communist assets,” German citizenship which had been granted to them after the First World War was withdrawn.

After the occupation of the Central and Eastern European countries by the German Reich, the Jews living there were denied any citizenship – they became stateless.

With the “11th Decree of the Reich Citizenship Act” in November 1941, the German Government automatically withdrew German citizenship from all German Jews living abroad. At the same time, in October 1941, Jews were banned from leaving the country and the systematic deportations to the concentration and extermination camps began. The abandoned property of the people who managed to escape or those who had been deported, was confiscated by the government.