I first left my home country of Guinea for Mali. I lived there for three months. But it was hard there, I didn’t get any food. It was very unpleasant. I met a friend who said he wanted to go to Burkina to get some food. So I went to Burkina together with the friend. We stayed there for a few days. There I talked to smugglers. I didn’t have any money, so he said: If you bring us customers, you can go with us in the end. I did that and in the end I got to Niger. There, life was also very hard and I couldn’t stay there. I met an acquaintance who had lived there for a long time. He asked me what we were doing here and we explained to him why we came here, but that we had to move on. And he said he could help me. I told him I didn’t have any money. He said, “That’s not a problem. I will take you from here to Libya. I will also give you work in Libya and from the wages you can give me back my money.” We did that, but we got to the wrong person. He was just messing with us.

When we came to Libya, he said, “Here is my house. Wait a minute.” We waited together with Arabs. There were many people in the house who had been there for a long time, some had been there for more than four months. We asked them, “Why are you still here?” They said, “They sold us out.” They make a trade there sometimes, like with slaves. I never expected this, I thought I would be working in Libya. But that’s how it was. When the big boss arrived at the house, everybody had to pay money. I was like, I don’t have money. So I was supposed to call my family and tell them to send money so I could get out. I said, “I’m sorry, but we don’t have any money. You saw for yourself when you came to get us, we had no food, nothing. Where are we going to pay for this? My family doesn’t know where I am either.” They beat me and everything. I stayed there for a long time, many months, two, three, four, in that house. I said to the boss, “Please, let us out for now. Then we can work and with that we will get money to pay you. Otherwise, we have no way.” To which the boss said, “Fine, you can go out, but if you don’t come back, we will look for you and kill you.” I then went out with an acquaintance and said to him, “You know what, no matter what happens, I’m never coming back here.” So we went out together into the city and saw some other African people and talked to them. We told them, “We came here, we were sold, we got lucky and got out, but we don’t know where to go. If they find us, we’ll be in trouble.” The other one said, “I’ll try to help you. You can come home with me.” But there were a lot of people there, too, and after a day the police came and arrested us all and sent us to jail.

In the prison we were also a lot of people, but once we managed to break open the door and some managed to get out. We walked through the night and saw a lot of people sitting there and sat down so that we wouldn’t be found. Then someone came with a truck, a cooler, everyone got in, then it was closed and we drove off. I asked the people, “Where are we going?”. And they said, “We’re going to Tripoli.” And I said, “What is that? Where is that?” They said, “That’s the capital.” When we got to Tripoli, we were in a house again, from the smuggler. They came at night and we all had to get up and were taken to the sea. My friend and I didn’t even know what was happening to us, why we were there, what we were doing here. When we arrived, there were people building a boat and pumping it full of air. My friend asked, “What are they doing?” I didn’t know. Then we had to get in the boat and we asked, “Where are we going?” And they were like, “We’re going to another city, Benghazi.” But actually, everybody knew it wasn’t like that. After more than six hours, we asked, “Oh, it’s that far to Benghazi?”. But nobody answered, because nobody knew, or rather, nobody wanted to say anything. The others had paid money, they knew exactly where we were going. But the two of us had not paid, we had just sat with the people by mistake. Then it became morning and there was nothing but sea to be seen. I was scared, but I also had no idea what to do. I had never seen anything like it in my life. At noon I cried a little bit because I was really scared. I had never seen such a big water. I also felt sick because of the gasoline. Me and my friend encouraged us, “We’re going to stay no matter what. We have to look and wait.” Drivers were always changing, so there was no one to ask where we were going. All you could do was be patient. Then we saw a big boat and thought it was Navy. But it was a pirate boat, they asked us all for money. They said, “If you don’t have money, we’ll let the air out of your boat.” And they beat us. But nobody had anything and then they let us, because they knew themselves that we had nothing. Some other people had to give their cell phones instead. We were in the middle of the Mediterranean. All the drivers were tired. They said all we can do is wait and pray that someone will come and help us. We waited there for almost an hour. Then a boat came behind us, they also wanted to go to Italy. Our boat couldn’t go on because it was broken, but the others could, and they said, “Unfortunately we can’t help you, but if you still have cell phones, we can call you. If we meet others, we’ll let them know you’re still there too.” We then waited for a long time. Then a small lifeboat came. They were going to rescue us. But everyone was tired and when they tried to give us the life jackets, the boat overturned. Most of them died. I haven’t seen my friend since then. I don’t know if he was rescued, if he is still alive or died, where he is. We had met in Burkina. It could be that he died. Or he made it and he was taken somewhere else in Italy.

In Italy, I went to a home for minors in Catania, Sicily. I stayed there for five months. Then they sent me to another home in Messina. I was not really healthy there and many things were not clear. That’s why I came to Milano, but there I had no care and I slept on the street. I met someone there who said he was going to Germany. And I came with him. And so I came to Germany at the end of 2017. First to Bavaria. My acquaintance said he wanted to go to Berlin because he knew someone there, and no one here. So I was like, “Yeah, I don’t know anyone here either, so let’s go to Berlin together.

Aliou B. left Guinea alone at the age of thirteen in 2014. At that time, the Ebola pandemic was raging in the already extremely poor and structurally weak country, which was characterized by corruption and violence. Even though Guinea is now officially governed democratically, human rights violations from the long period of military dictatorship continue. Opposition figures are brutally cracked down on.

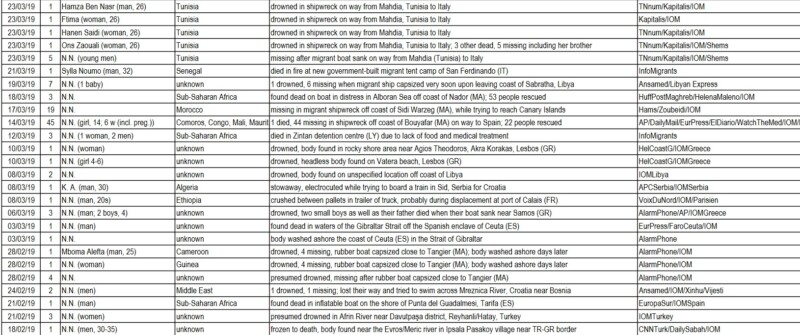

Aliou’s route via Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger and Libya is considered one of the most dangerous escape and migration routes in the world, killing at least 72 people a month. However, the number of unreported cases is very high. Exactly how many people die, disappear or are injured on this dangerous route is not clear, because the routes that lead forced migrants from West Africa to the North African Mediterranean coast are controlled by human traffickers and smugglers. People here are exposed to extreme human rights abuses and threats to life and limb: arbitrary killings, torture, extreme violence, and rape. The governments and official security forces either lack the power to act against them or are themselves implicated in these abuses.

Aliou describes how he was held and abused for months in Libya by human traffickers in order to extort money from him or his family. After freeing himself from this captivity, he was arrested by Libyan police and detained in one of the many camps and prisons where forced migrants are arbitrarily sent and held in inhumane and violent conditions. Libya is not a signatory to the Geneva Convention on Refugees and in principle does not offer the right to asylum, so all migrants who arrive there are automatically criminalized for “illegal migration.” Despite the extensive human rights violations against refugees and migrants in the civil war-torn country, the EU cooperates closely with Libya and supports the country financially to prevent migrants from fleeing to Europe.

During a mass escape, Aliou escapes from prison and accidentally gets caught up in a group waiting to be taken across the sea to Europe. Not knowing what is happening to him, he boards the makeshift overnight boat, which is attacked by pirates and eventually wrecks. He witnesses many people drown in the panic that erupts as a lifeboat approaches. Aliou loses sight of the friend with whom he had traveled much of the journey so far: to this day, he does not know if the friend survived the accident, or where he might be.

After initially spending several months in shelters for minors in Sicily, but not being adequately cared for there, he finally arrived in Germany at the end of 2017.

Aliou’s narrative bears witness to the traumatic experiences that many forced migrants go through in their search for a safe place. Most of them do not manage to get to such a safe place to tell about these experiences: They remain trapped in camps and prisons, missing, or have lost their lives along the way. For the people who nevertheless reach Europe and Germany, there are often no adequate structures to deal with the traumatic experiences: Instead, new concerns about insecure residency status, among other things, are added.

The interview with Aliou B. was conducted by We Refugees Archive in December 2020.