Excerpts from an interview „Edith Hillinger: Building a Life, San Francisco, June 2006“, geführt von Richard Whittaker

RW: You must speak Turkish.

EH: I did speak fluent Turkish, but it’s not really with me anymore.

RW: How do you think your childhood in Turkey has affected you.

EH: Well, I’ve thought about it. I still get very upset when I view programs about the Nazi era, the killings. My father’s brother died in Auschwitz, so it’s a very upsetting thing. Yet I’m grateful that I didn’t grow up in Germany. The gift of that whole trauma is that I went to a country that for my artistic development was much more interesting. I never see myself wanting to have had the middle class German childhood. Strangely, I much prefer my refugee childhood. But my brother went back to live in Germany in the sixties! That’s where he lives. He’s a professor there. It’s this western, homogenized neat, orderly society.

RW: I see, the German model.

EH: That model seems gray and uniform, to me. Istanbul is a wild bazaar, a wild chaos of color, languages, food, everything mixing! It was like an early version of New York. It was full of life and full of color. My grandmother, on the outskirts of Berlin, had one or two oriental poppies in her garden, but when we got to Istanbul, there were fields and fields of red poppies as far as the eye could see! It was a whole other kind of thing. That’s what I think I was really happy with.

RW: All that life.

EH: The color, the life, the variety, everything! It’s strange to say, but because of the war, I landed in a place that I really loved.[…]

RW: I remember you telling me about time you spent as a very young child in your grandmother’s garden in Germany.

EH: I associate my love of nature and of plants with my grandmother who was wonderful at growing everything. My parents really didn’t have much interest in plants or animals, like I have. They were very much “city” people. I don’t think they even had a philodendron [laughs].

My grandmother and grandfather had a very small family farm on the outskirts of Berlin. […]

So I often was sitting next to my grandmother as she was tending the animals and the plants and the flowers. She had poppies in her garden, too—and then getting to Turkey and seeing these familiar plants, seeing that plants travel just like people do. Poppies travel all over the world. Many of our plants are from China. They’re migrants, too. I think that was a source of comfort for me. Everything else was unfamiliar, the people, the language, the customs, but plants were familiar, in some way. I remember sitting under a pomegranate tree just when the fruit would fall and burst open, just studying the way the seeds inside looked.

RW: What was that like, looking at those pomegranates?

EH: I think it was a non-threatening relationship that took me out of myself. The family relationships, and the relationships with others, were always fraught with various problems. And the war was very difficult on my parents. My mother was very attached to her family, so she felt cut-off. My father, the more gregarious one, was quite nervous about not being able to save his brother, and the loss of his family, too. And having to flee a second time, already. So there was all this unspoken stuff. I don’t know what it would have been like to have had a family life that wasn’t overlaid with all these sorrows that the adults had.

RW: Are there any other experiences you would include, and what do you think of these experiences, that they persist and are still present?

EH: What comes to mind is that these experiences are beyond the stories we tell others about ourselves, and therefore, they’re more true, in a way. The stories we tell others sort of become set in concrete. They reflect the way we want others to see us. Those early experiences go beyond those more superficial stories.

RW: Do you remember being in gardens in Turkey?

EH: It wasn’t so much gardens, but the poppies grew wild in the fields. My parents took us on walks over the hills on both sides of the Bosporus every weekend, and we’d see fields of flowers. They’d just be there in the summertime, although there were little gardens of wisteria and things like that, too.[…]

RW: Getting back to history here, was your father influenced by Bruno Taut’s Japanese collections? And did that Japanese influence come into your home?[…]

EH: Now you were asking did a Japanese influence come in? Yes. Soon after we came to Turkey, Bruno Taut died. In his will, he left a portion of his Japanese collection to my father. That included a scroll and that’s why I paint the narrow paintings, as you see [pointing]. It included a case full of fans and toys that I played with, and that I still have. I’ve always been interested in Japanese culture and now Japanese gardens, as well. That came from that connection, I think.

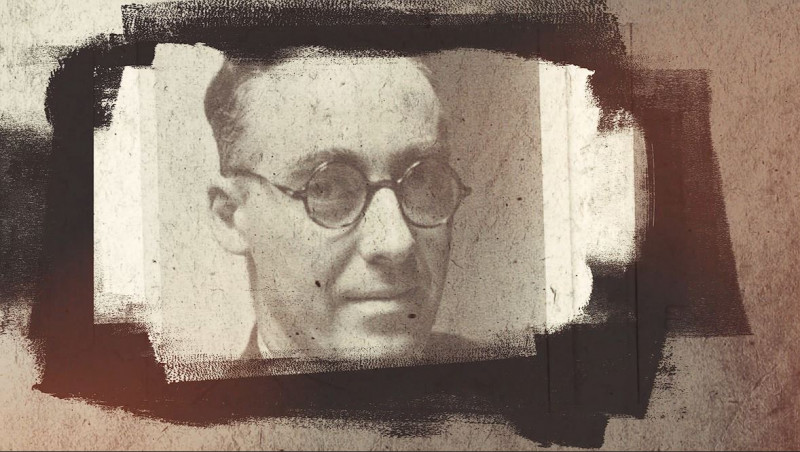

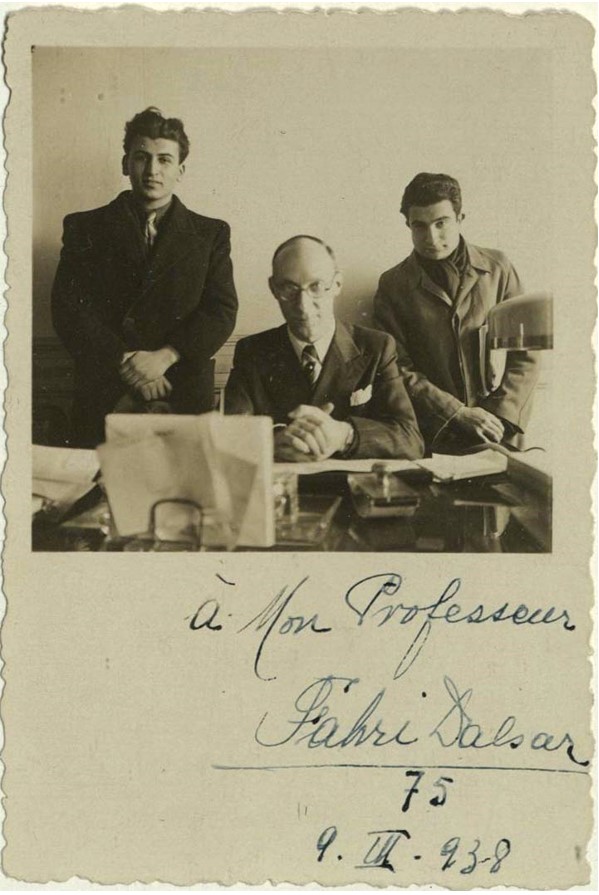

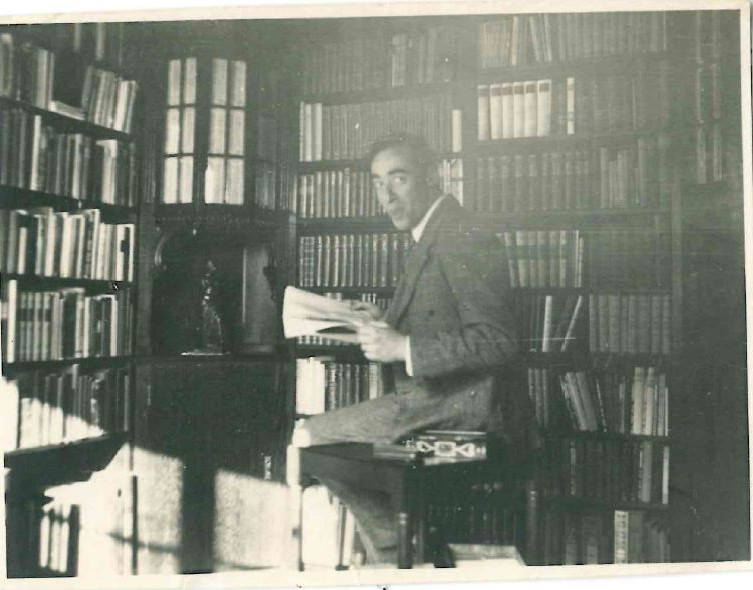

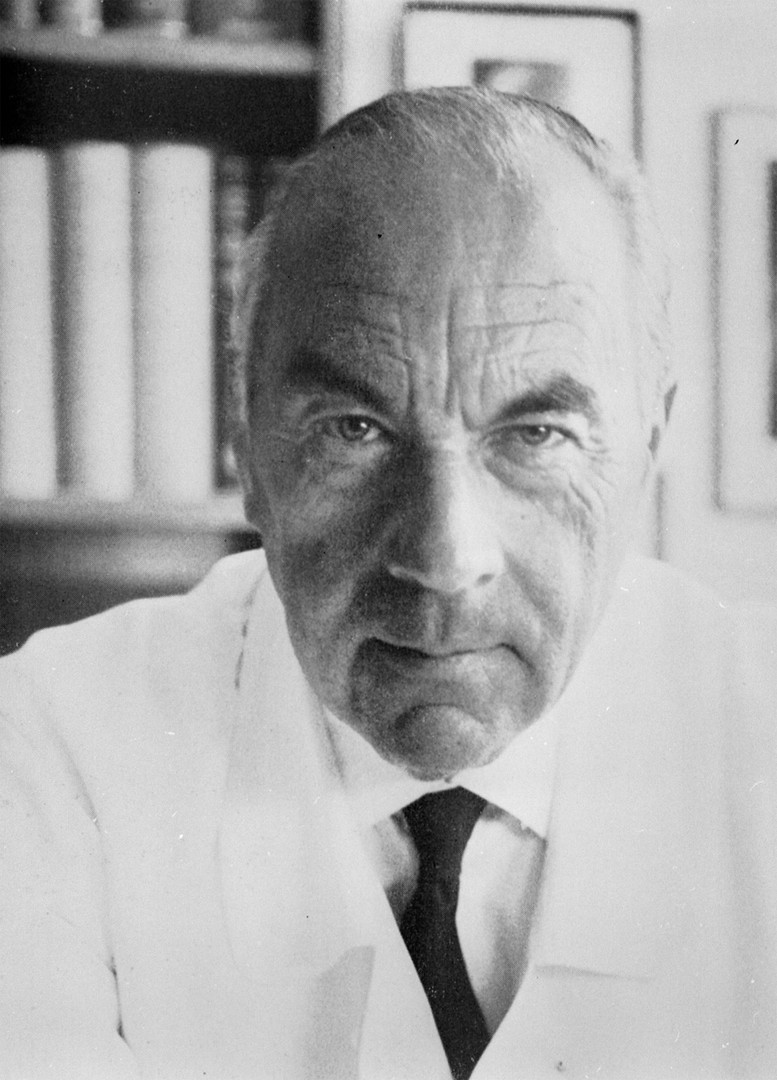

Edith Hillinger, born in Berlin in 1933, fled with her parents from Nazi Germany to Istanbul in 1937. Her father Franz Hillinger had already fled from Hungary to Germany after the First World War, after being barred from studying there as a Jew. In Turkey he worked together with his mentor Bruno Taut, who had already come there in 1936 and who was given important positions to reform Turkish architecture. In view of the few opportunities to escape, Edith Hillinger describes the job offer as a lifesaver.

When she was 16 years old, Edith moved on to New York City with her mother. Since then she has lived and worked in the USA as an artist. Her art is also influenced by the impressions of her childhood and youth in Istanbul.

In this interview, she talks about how she perceived the colorful atmosphere of Istanbul as a child and the oppressive burden of exile in her family. She also explains how nature became a constant in her life and art.

Excerpts from an interview conducted by Richard Whittaker on June 24, 2006, originally published in Works & Conversations.

We thank Edith Hillinger for kindly allowing us to use the excerpts from her website: https://edithhillinger.com/intervie