Regine Erichsen

Emigration to Turkey

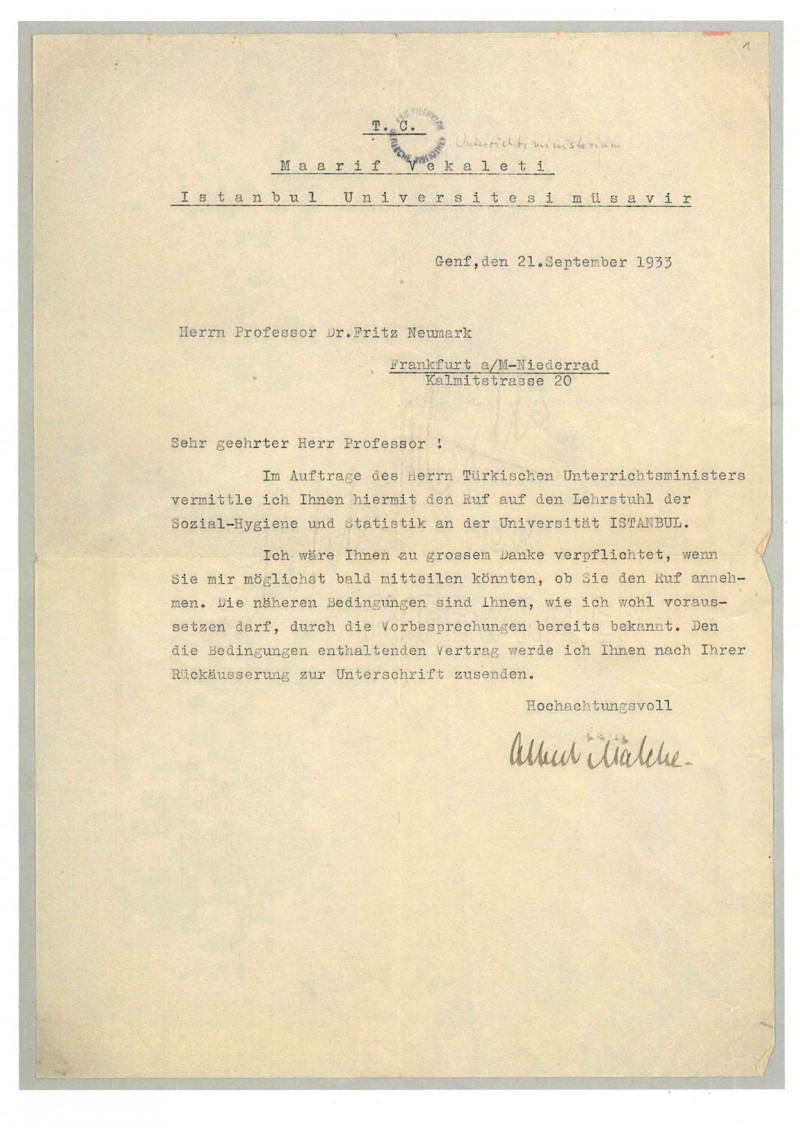

Female academics and professionals, like their male counterparts, were being expelled from Nazi Germany from 1933 onward because of their Jewish ancestry or their anti-Nazi stance. As émigrés in Turkey these women became part of the major reform of state and society initiated by Kemal Paşa (Atatürk) in the wake of the founding of the Turkish Republic. At the centre of this project, pursued by Turkey’s one-party state, was Istanbul University (Istanbul Üniversitesi, IÜ), which reopened in 1933 and remained the only university in the country until the founding of Istanbul Technical University (Istanbul Teknik Üniversitesi, ITÜ) in 1944. It was conceived as a model institution whose goal was to train a generation of young Turkish scientists and experts who would become pioneers of the New Turkey. To realize this plan, the Turkish reformers appointed German and Austrian professors to the chairs of the IÜ (and the universities later to be set up) and with them assistants and technical staff, including 20 to 30 women. Not one woman was given a full professorship at the IÜ. But the lower-level female departmental staff, along with their male colleagues, also played an indispensable role in this transfer of technology and science performed by émigrés.

At that time Turkey was still on its way to becoming a modern industrial society. The female émigrés bridged the gaps in the initially weak infrastructural foundations of the IÜ and helped overcome, as far as possible, the deficient qualifications of prospective students whose school-leaving qualifications reflected a Turkish school system that was still being developed.

About 300 academics and professionals moved to Turkey at that time, most of them taking posts in Istanbul. If we include their close relatives, the total influx came to roughly a thousand.

The University of Istanbul sparkled at the top with some leading figures from German academia. But without the efforts of their supporting staff in the departments, Turkey’s project of science and technology transfer from Germany to the IÜ would very likely have failed. What characterised the appointment of the foreign chair holders at the IÜ, but also of their departmental staff, was that they were recruited to Turkey because they were needed there.

But the paths of women in this Turkish emigration project are not easy to trace. For their lives in exile are often overlaid by the exile stories of the well-known men who assumed leading roles in academia, science and the arts. Accounts of the exile of academics and artists from Nazi Germany have tended to push women’s stories into the background, obscuring their role behind their husbands, male colleagues and bosses.

Women in Turkish Exile

Both men and women were forced to give up their jobs and careers in Germany at that time. But once in exile, those women who had formerly worked would often find themselves in a caring role within the family. Reporting from American exile, the writer Alfred Kantorowicz notes that the man “writes through the night and at half past seven the woman comes along. They eat cheese sandwiches.”

These women had an important role in the survival of the family in exile and they mastered the difficult challenges of a foreign environment. This was also the case in Turkey.

Alice Sievert, the daughter of Felix Haurowitz and Regina Haurowitz, recalls the important role of wives in the lives of Istanbul’s emigrant professors: without them it would have been difficult for their husbands to carry out their work. It was typically the mother of the family who found an apartment in Istanbul, who, armed with a Turkish-French dictionary, arranged household help, who did the shopping at the weekly market and prepared German dishes for the family following the cookbook she had brought with her, having first washed every lettuce leaf to avoid typhoid infection. Felix Haurowitz, who held the chair of Biological and Medical Chemistry at the IÜ from 1939, emigrated with his family from Turkey to the USA in 1946.]

Nor would it have been easy for wives to find work easily on the labour market in Turkey. The right of residence granted to relatives was tied to the contract holder, and work was hard to find for ‘co-exiles’ due to restrictive alien laws in the context of the country’s state-led economy at that time. For example, physicians were not allowed to open a private practice. Some women therefore worked on a voluntary basis or engaged in private research into Turkisch culture. For example, the ethnologist Leonore Kosswig learned Turkish board weaving and wrote about it. She chose to remain in Turkey when her husband, the zoologist Curt Kosswig, (from 1937 at the IÜ), went to Hamburg in 1955.

Turkey was not a country that generally promoted immigration, and most émigrés moved away in the 1950s. Unlike in other countries of refuge, academics and professionals were, however, appointed to positions in Turkey, including at the IÜ. The IÜ was subordinated to the Turkish Ministry of Education and received autonomy only 1946. The appointment of foreigners was made by decision of the Council of Ministers of the Republic.

Émigrés at the University of Istanbul: Working Conditions

As they entered the country with an employment contract, the new arrivals in Turkey did not have to search for work and create a livelihood for themselves like so many of their colleagues in host countries like the USA.

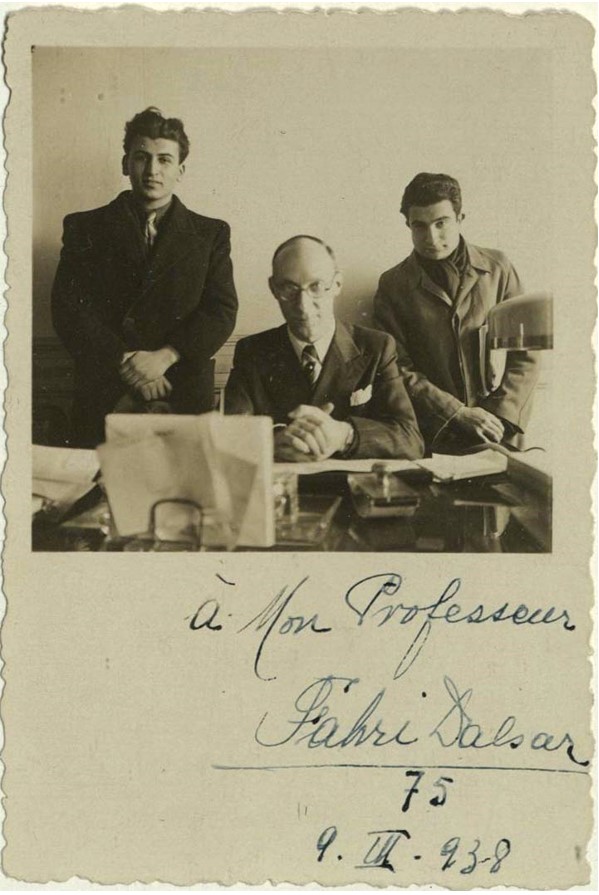

Like their male colleagues in assistant roles, the women working in the departments at the IÜ were considered ‘small fry’ compared to the much vaunted full professors, although there was actually closer personal contact between full professors and assistants in Istanbul than in Germany. This is how Traugott Fuchs from the chair of European languages (1934 to 1943), describes it.

Staff and assistants at the IÜ were paid much less than the department chairs and they were given only short-term contracts. This shows the assessment of the importance of the departmental staff on the part of the Turkish reformers. They apparently believed that they could easily dispense with the services of these ‘retainers’, once the work of establishing a chair was completed.

A special restriction for the scientific assistants is described by the chemist Lotte Löwe (1933 to 1954 at the IÜ), assistant to Fritz Arndt at the Chair of Inorganic and Analytical Chemistry:

“Most of us, my young colleagues and me, had been dismissed from assistantships at German universities, positions we had often held for a long time – in my case, for example, for 6 ½ years, and I had been appointed as a civil servant on probation after the first two years as a regular assistant. In Istanbul, we were classified as `ilmi yardımcı’ (research assistants). But we young German scientists – about forty to fifty in number – had, with few exceptions, practically no chance of advancement as guest workers.”

Advancement through habilitation was reserved for the Turkish assistants who were designated to take over the chair of an émigré professor. They had mostly studied abroad on a scholarship and acted as translators for the émigrés in the reform project. They, too, were indispensable to the reform project with foreigners.

Famous academic émigrés and their success described in their autobiographies

The German professors report on their team members only in passing. Autobiographies and reports on the Turkish emigration tend to highlight ‘great names’ such as Erich Auerbach (representative of the language theory of stylistics), Friedrich Dessauer (a co-founder of biophysics), Hans Reichenbach (an initiator of logical positivism) or Richard von Mises (a pioneer in the fields of applied physics and mechanics). Wether these important figures of the international science history had any impact on the emerging Turkish university landscape and Turkish science history is not mentioned.

The accounts of academic emigration generally fail to explain how the emigrant professors were able to turn a difficult initial situation at the IÜ, newly opened in 1933, into an operationally satisfactory institution in terms of teaching operations and research projects.

One of the first women appointed to the IÜ was Lieselotte Diekmann, a lecturer at the IÜ’s Department of European Languages from 1933 to 1938. She writes about her first impression of the university:

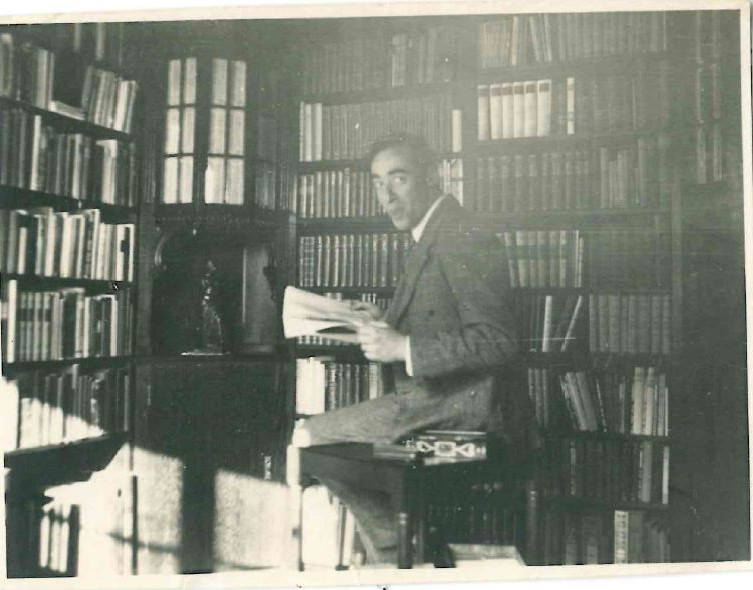

“Every institute director from that time can tell countless tragicomic stories from the construction phase. For instance, they had forgotten to lay the electric wires in one of the new buildings, so when the professor entered his turnkey institute, there were plugs and switches but no electricity. Or a botanical garden had sent plants to the Botanical Institute, but clearance for the importation of the plants was not given and the plants died in the customs office. For the humanists, beautiful old manuscripts had been acquired but, of course, there was no library. Only those who had a private collection and could bring it with them could have books at their disposal.”

The overcoming of these difficulties is described by Rudolf Nissen, who held the chair of surgery at the IÜ from 1933 to 1939, exclusively as his own achievement. He mentions “the rather primitive external working conditions, which actually had the stigma of a provisional arrangement during my entire Istanbul period. [ … ].” And he continues, “Today, looking back over 50 years of professional activity, I consider it remarkable that I was able to create a satisfactorily functioning university hospital in those six years under such inadequate external conditions.”

How had this positive development come about? Could Nissen have achieved all this on his own?

Philipp Schwartz, who held the chair of Anatomical Pathology at the IÜ from 1933 to 1953, paints a similar picture of the beginning of his work at the IÜ: “In the medical faculty […] an unbearable situation soon developed. The theoretical institutes [ … ] received form the old medical school the cabinets, tables and chairs, and in addition the quite meagre, outdated and largely completely useless apparatus and instruments. [ … ] We were not intimidated. We improvised.” He goes on to describe how clinicians found themselves in a similar position. But here, too, what seem to be impossible then happened: “Word had spread throughout the country that our operators, Nissen, Liep(p)mann and Igersheimer, were performing miracles. [ … ]. The clinical lectures were lively and topical. One operated all day long.” But it was not only this achievement as such that he reports. In view of the initially controversial position of the numerous foreigners at the IÜ among the general public in Turkey, Schwartz wrote: “These three clinicians decided the fate of the university reform.” Thus, the local resistance to the appointment of foreigners collapsed and it was decided that the émigrés could stay. But was this thanks to a miracle?

5. The female émigrés as specialists at the IÜ

Hardly. The task was to build a modern university system, starting with the IÜ as a model. Any attempt to achieve proper standards for the experiment based teaching of specialist subjects would have been doomed to failure in the 1930s without a transfer of the corresponding technology. The IÜ was equipped with this technology, and its use required experts with the appropriate specialist training. Take an example from radiology: The X-ray nurse Margarethe Reiniger (at the IÜ from 1938 to 1943) and the X-ray assistant Esther von Bülow (from 1938 until after 1949 at the IÜ) supervised the university’s Radiological Institute in their respective roles. Esther von Bülow’s qualification included a grounding in chemistry and physics, anatomy, physiology and biology, microscopic-anatomical techniques, parasitology and serology, clinical chemistry and microscopy, photographic technology, macro- micro- and colour photography, radiology, drawing, stenography and typing.

At that time, the (vocational) education system in Turkey was not nearly ready for training graduates to work in modern laboratories. The reformers plan for operating the laboratories and workshops and designing therapy plans and textbooks was to appoint the necessary experts.

The women among them were medical-technical (specialist) assistants such as Esther von Bülow, operating room nurses and other specialist nurses, a specialist draftswoman; and a librarian was responsible for building up the library. The scientific assistants supervised the research series and the work of the Turkish assistants, and they also held tutorials, as did the female lecturers. They organized the seminar work and also taught at the language school of the IÜ to prepare the students for the philology subjects.

On the surface, the field of activity of the women in question did not differ from the tasks they had performed in Germany. In Germany, it was the customary routine of full professors to be surrounded by employees with special training.

Female émigrés as pioneers of the university reform

However, the fact that the women in question did pioneering work in Turkey is hardly reported. They encountered working conditions in Turkey that were completely different to those they had been used to in Germany and Austria.

The situation at General Clinic III, later General Clinic II, of the IÜ’s Department of General Medicine serves here as an example. Erich Frank from Breslau, known for his research on diabetes mellitus, was appointed to this chair in 1934. To set up the laboratory, Frank arranged for his former assistant Kurt Steinitz (1934-1943 at the IÜ) and his sister-in-law Erika Bruck to join his team at the IÜ. Erika Bruck was a medical trainee with Frank at the Wenzel-Hancke Hospital in Wroclaw after she had completed her doctorate. Erich Frank conducted research in Turkey on his specialisms and introduced to Turkey the treatment of diabetes mellitus using the methods he had developed. “The treatment was carried out at the Guraba University Hospital by establishing a diet especially adjusted for the respective patient, based on daily urine samples, blood glucose measurements and measurements of other blood values,” reports Frank’s student and colleague Ferhan Berker.

Bruck and Steinitz provided the laboratory data for this treatment. Erika Bruck writes:

“My most important teacher was Erich Frank. […] Around 1929, he developed the first per os drug for diabetes mellitus. Frank headed the General Medicine Department at Guraba Hastahanesi, one of three General Departments at Istanbul Üniversitesi. The laboratory was not a research laboratory (although scientific research was done in this laboratory on the side) but a clinical laboratory where daily urine and blood tests were conducted for patients. In the first year, 1934-35, we built a pretty good laboratory from scratch. Among other things, there were no laboratory technicians with relevant training, no distilled water, which we had to produce ourselves for years, no apparatus or glassware, which we, completely inexperienced and naïve in trade and business, had to procure by importing from Western Europe in state of politically upheaval and economic depression. […] Urease for the determination of urea in the blood we made ourselves, if I remember correctly, from soybeans.”

The successful treatment of diabetes also required a special diet. For its implementation, Frank applied for the appointment of dietary nurse Else Wolf, who had already been his long-time colleague in Breslau. He describes her in his application as perfect in scientific dietetics and in the art of cooking. Else Wolf adapted the dietary regulations to Turkish eating habits and wrote a corresponding textbook of practical dietetics about it.

Ferhan Berker wrote on this subject in 1959: “Today in Turkey we find hundreds of physicians who are implementing Frank’s findings on diabetes in a way adapted to Turkish conditions.” When Frank died in Turkey in 1957, he received a state funeral in recognition of his accomplishments in the country. Without the contribution of his collaborators, his successes would hardly have been possible.

The fact that his professorial colleagues also depended on such valuable work is shown by the applications for contract extensions for female employees submitted to the dean’s office of the IÜ for forwarding to the Ministry of Education. The ophthalmologist Joseph Igersheimer (at the IÜ from 1933 to 1939) performed his spectacular operations with the help of his laboratory assistant Susanne Hofmann. She assisted Igersheimer in his operations, since a Turkish nurse had not yet been trained for this task. The same help was given to Wilhelm Liepmann (1933-1939 at the IÜ), the professor of gynaecology. Rudolf Nissen operated with the assistance of his surgical nurse, Irmgard Althausen. So they all performed their much praised miracles with the help of expert female staff.

Requests by the full professors for extensions of contracts were granted with the support of their Turkish colleagues, as the Turkish administration clearly recognized the importance of these female émigrés for university reform in view of the success of the academic emigration project. By 1942 Lotte Löwe at the Faculty of Natural Sciences could claim “that the laboratories and libraries were in very good condition […] and that the chemist training was about the same as in the former Breslau Institute until 1933.”

Women´s education in the Turkish schooling system

Erika Bruck eventually headed a laboratory herself, at the Haseki Clinic of the IÜ. The head of the General Medicine Clinic was Professor Akıl Muhtar Öktem, of Wilhelm Liepmann’s Chair of Gynaecology. Bruck writes: “As before at the Gureba, all equipment materials and methods had to be built up from scratch. Akıl Muhtar supported all my endeavours, so that I never had much to do with administration or finances, for example.”

Erika Bruck’s work brought her into contact with Turkish women. She writes,

“Haseki Hastahanesi had only female patients. When I went to draw their blood for laboratory tests I often asked them about their family and living conditions, whether they could read and write. Some had ten children, three or four of whom survived childhood. Most of the women were more or less toothless by the time they reached the age of 40. But among the students at the university, at least 20% were women, although fewer in medicine than in other fields.” These observation points to the great social disparity between rural Anatolia and Turkey’s urban centres.

Educational reform was one of the measures taken by the Turkish Republic from its foundation in 1923 that were designed to eliminate this disparity. A language reform and corresponding literacy programs formed a uniform basis for access to education. A nation-wide school system was gradually established, with a special emphasis on educationally disadvantaged parts of the country. Coeducation was introduced and scholarship programs were established, from which girls could also benefit. The urban classes, however, already had a longer tradition of education. Girls from well-off Turkish families had, under the Ottoman Empire, already been graduating from minority schools (azınlık okulları) of Istanbul and had been studying abroad. Take, for example, the case of Doctor Safiye Ali. After completing her doctorate and residency in Germany, she became the first woman, in 1923, to open a practice in Istanbul. In 1937/38 there were as many as 229 women studying at the Faculty of Languages and Literatures of the IÜ, but only 188 men. At the Faculty of Medicine, 115 female students were enrolled in the same academic year, compared to 1,576 men, for medical studies. At the Faculty of Science, the ratio in the corresponding academic year was 262 female to 399 male students. Erika Bruck’s observation on the distribution of male and female students among the fields of study reflects this statistic.

Opportunities for women at the IÜ continued to develop. In 1945, 11.66% of the graduates of the Faculty of Medicine of IÜ were female. Some of the emigrant professors had female successors even in subjects with relatively small numbers of female students. Thus, the chair of Hans Winterstein, full professor of physiology at the Faculty of Medicine from 1933 to 1953, was taken over by Meliha Terzioğlu. The chair of astronomy held by Wolfgang Gleisberg (from 1933 at IÜ, from 1954 chair holder) at the Faculty of Natural Sciences, was given to Nüzhet Gökdogan after Gleisberg’s retirement. Women at the IÜ were therefore not at all unusual in the time og the emigrants. .

How the female émigrés left Turkey

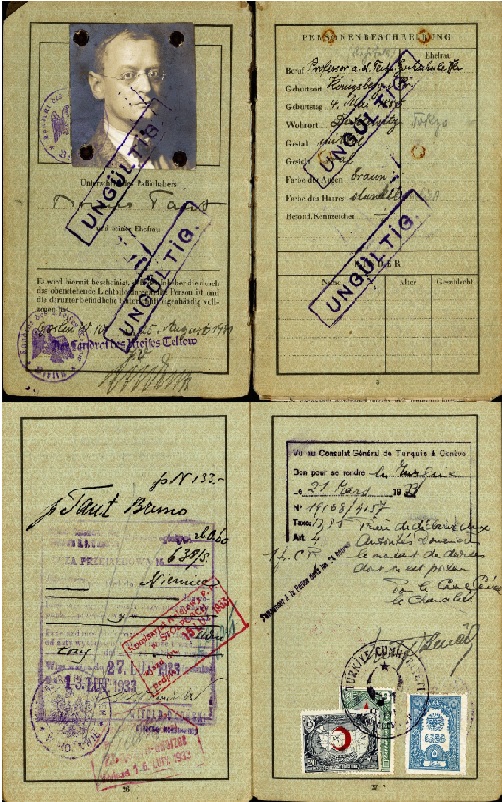

In 1941, the Reich expatriated all emigrants subject to the relevant Nazi legislation. The Turkish authorities recognized their precarious emigrant status with the entry ‘haymatloz’, stateless, in their residence papers. Some of the émigrés working at the IÜ had voluntarily followed their expelled bosses to Turkey. Some had left Germany before the Nazi administration had registered them or had been able to arrest them for political activities. Those émigrés kept their German passports.

In 1944, Turkey broke off relations with Germany. Those who still held passports were allowed to return to Germany. If they wanted to stay, they were interned, even if they saw themselves as emigrants. Whether they were emigrants or not, most non-jewish Germans and Austrians returned from Turkey to liberated Germany and Austria after 1945.

Even before 1944 the limited career prospects open to the academic émigrés in their subjects led many, if possible, to migrate on to Palestine or the USA. The aid organization ‘Notgemeinschaft Deutscher Wissenschaftler im Ausland’, represented by its founder Philipp Schwartz at the IÜ, arranged such emigrations to a second country of refuge, operating through the Society for the Protection of Science and Learning (SPSL) in London. The two relief organizations worked together.

Hilda Pollaczek (née Geiringer), came from Berlin to join her university teacher Richard von Mises at the mathematics department of the IÜ. She then wanted to follow von Mises, who had accepted an invitation to teach at Harvard University in the USA. Her letter to the secretary of the SPSL shows how worried she was about not finding a position as a woman in the US:

“Please would you consider that it is much more difficult for a university woman to find any position than – under similar circumstances – for a man. Because there is in many cases the added difficulty that university posts are not given to women.”

Fearing she would not get the papers for entering the US, she finally writes to von Mises: “Is there no way to marry pro cura? An emigrant here [in Istanbul, author’s note] who has a residence permit married his ‘bride’ and she was then permitted to join him directly from Vienna.”The SPSL eventually placed Hilda Geiringer as a ‘lecturer’ at Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania. In the US, she did then marry Richard von Mises.

Helpful for such mediation were publications written by the women academics about their research projects at the IÜ conducted with colleagues and full professors. One example should be mentioned here. The dermatologist Berta Ottenstein ran the laboratory of the Cancer Institute headed by the pathologist Siegfried Oberndorfer in the chair of General and Experimental Pathology (1934 to 1938). She wrote a publication on the results of research at the institute.

Within the framework of the reform project, the IÜ also sent ‘its’ émigrés abroad to academic conferences, not least because they raised the international profile of the Turkish university. Berta Ottenstein was one of the participants at conferences in countries outside Turkey that had not been Nazified. She represented the IÜ at the 3rd International Microbiology Congress in New York in 1939 with a paper on cancer research from the Institute. After emigrating to the United States, she obtained a position as a research fellow at Harvard University. Back in Germany after the war, Ottenstein was awarded an associate professorship in 1951.

Erika Bruck was also able to continue her career in the United States. She moved there in 1947 and became a professor of paediatrics at the State University of New York, Buffalo from 1969 to 1978. She saw her experience in Turkey positively, writing in retrospect:

“Although my work in Turkey interrupted my medical training – after my year as a medical intern – it taught me much that would help me later, even if it was not officially credited toward my career: not only laboratory techniques but much about the role of laboratory science in medicine. I learned, mainly from my brother-in-law, how to achieve goals without compromising quality without tools that are considered indispensable in Central Europe. Through contact with Turkish students, patients, and – on trips far into the hinterland of Anatolia – ordinary Turks in small towns and villages, I learned a great deal about the influence of schooling, public hygiene and the environment on the health of individuals as well as on the population as a whole.”

Like Erika Bruck, female émigrés at the IÜ were not only victims in their experience of expulsion and flight but showed creative agency transforming their fate to the better. At the University of Istanbul, they made a decisive contribution to the university reform in Turkey.