The Arrival of Hannah Arendt

This film describes the arrival of Hannah Arendt - a Jewish, German-American political theorist and publicist - in New York and her reflections on flight and helping people start over.

Nein, an eine Rückkehr nach Wien habe ich niemals gedacht, den mit meinen ehemaligen Landsleuten, den Österreichern, will ich nichts mehr zu tun haben. Man muss aber keinen Hass haben und keine Rachegefühle. Man kann sich doch nicht genauso schlimm benehmen wie Hitler und die Nazis. 32 Mitglieder meiner Familie wurden deportiert und überlebten den Holocaust nicht. Nicht einmal die Mutter, der ich, nachdem ich im Dezember 1939 nach Amerika gekommen war, ein Affidavit geschickt habe. Darin sind die Amerikaner schuld. Mir ist klar, dass Amerika eigentlich meine Mutter umgebracht hat. Die Mutter (durch ihre Heirat noch ungarische Staatsbürgerin) hat von der amerikanischen Botschaft kein Visum erhalten, weil sie nicht im Besitz eines Passes war. Den hatten die ungarischen Behörden ihr nur ausgestellt, wenn sie mindestens drei Monate lang in Ungarn gelebt hätte. Aber das ging doch nicht mehr zu diesem Zeitpunkt. Ungarn war inzwischen auch okkupiert und verweigerte Juden die Einreiseerlaubnis. Und weil die amerikanischen Bürokraten kein Einsehen gehabt haben, ist das Affidavit verfallen. Und auch meine Mutter ist also deportiert worden, 1941 nach Linzmannstadt, und wie die anderen Verwandten umgekommen. […]

Ich hatte also noch genügend Gelegenheit, die österreichischen Faschisten kennenzulernen. Mir erzählt niemand, dass das alles nur eingewanderte Deutsche gewesen sind. Jedenfalls hatte ich ab dem Moment, da ich von Österreich fortgegangen bin, das Gefühl, meine Wurzeln sind abgeschnitten. Es war nichts mehr daran zu ändern. Vorbei. Da wird man von dem Land, in dem man sein Leben lang gelebt und gearbeitet hat, hinausgeworfen, und hier ist man sofort gleichwertig und als amerikanischer Künstler akzeptiert. Ich war so gerührt darüber,- so etwas gibt es in keinem anderen Land. Ich war damals noch nicht einmal ein Jahr in den Staaten. Ja,- since then I am an American craftsman… Stellen Sie sich vor, das State Department hat Sachen von mir gekauft, hat sie ins Ausland geschickt und vorgestellt als Werke einer Künstlerin ausländischer Herkunft, die die amerikanische Kunst beeinflusst. […]

Ich habe niemals ein Refugee-Dasein geführt. Es ist eher Zufall gewesen, wenn meine Freunde deutscher oder österreichischer Abstammung waren. Das war alles sehr kosmopolitisch. Ich habe mich nie in diesem sogenannten Emigrantengetto bewegt. Auslandsösterreicher sind doch aus freiem Willen im Ausland, oder? Das bin ich ja nicht. Ich bin doch nicht freiwillig aus Österreich weggegangen. Dass ich hier ein Heim gefunden habe ist ein anderer Kaffee. Österreicherin, das kann ich sagen, bin ich keine mehr. Ich bin und bleibe eine Emigrantin, absolut. Ich habe einen amerikanischen Pass und ich fühle mich wohl hier.

No, I never thought about returning to Vienna, because I don’t want to have anything to do with my former compatriots, the Austrians. But you don’t have to have hatred and feelings of revenge. You can’t behave as badly as Hitler and the Nazis. 32 members of my family were deported and did not survive the Holocaust. Not even my mother, to whom I sent an affidavit after I came to America in December 1939. In that, the Americans are to blame. I realize that America actually killed my mother. My mother (still a Hungarian citizen by marriage) did not get a visa from the American Embassy because she did not have a passport. The Hungarian authorities had issued her a passport only if she had lived in Hungary for at least three months. But that was no longer possible at that time. Hungary had been occupied in the meantime and refused Jews entry permits. And because the American bureaucrats had no sympathy, the affidavit expired. And so my mother was also deported, in 1941 to Linzmannstadt, and perished like the other relatives. […]

So I still had enough opportunity to get to know the Austrian fascists. Nobody tells me that they were all just immigrant Germans. In any case, from the moment I left Austria, I had the feeling that my roots had been cut off. There was nothing I could do about it. Gone. You are thrown out of the country where you have lived and worked all your life, and here you are immediately accepted as an equal and an American artist. I was so touched by that,- there is nothing like that in any other country. I had been in the States for less than a year at that time. Yes,- since then I am an American craftsman… Imagine, the State Department bought things from me, sent them abroad and presented them as works of an artist of foreign origin, who influences American art. […]

I have never led a refugee existence. It was more by chance if my friends were of German or Austrian descent. It was all very cosmopolitan. I never moved in this so-called emigrant ghetto. Austrians abroad are abroad of their own free will, aren’t they? That’s not what I am. I didn’t leave Austria voluntarily. The fact that I found a home here is a different coffee. I can say that I am no longer an Austrian. I am and remain an emigrant, absolutely. I have an American passport and I feel comfortable here.

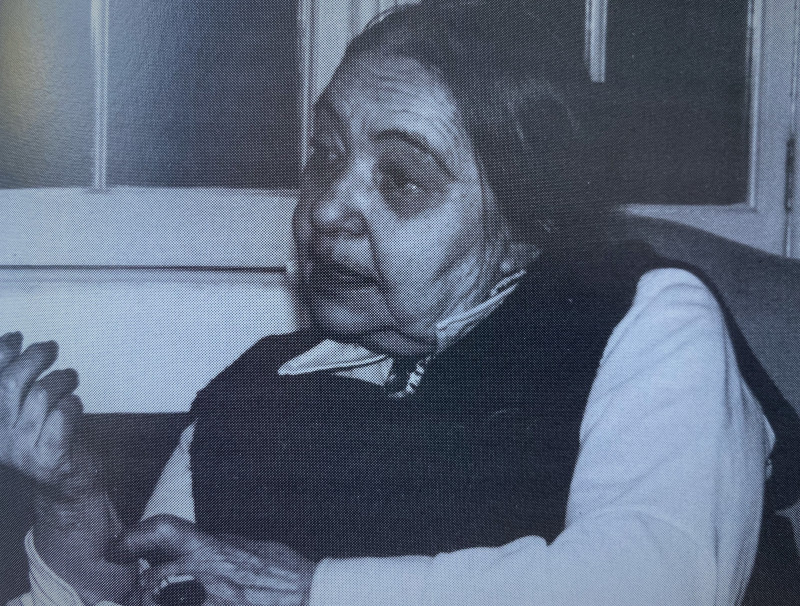

Käthe Berl was a well-known Austrian-American artist, she was born in Vienna in 1908 in a Jewish family. She trained as a costume designer at the School of Applied Arts in Vienna, also published a first book of poems and illustrations as a member of the Youth Art Class, and even took on the artistic realization of the designs of an American engineer living in Vienna. The friendship that developed with him and his wife in the process later became the cornerstone of her new life when it came to emigration and a new start in America. During the Nazi era, her family was deported and did not survive the Holocaust. At the end of 1938, with the help of a friend, she fled first to London and in December 1939 to New York. In the USA she quickly gained recognition as an artist and exhibited her artistic works in museums in New York.

Elfi Hartenstein, 1991: Heimat wider Willen. Emigranten in New York – Begegnungen. Berg am See, pp .64-70.

Translation from German to English © Minor Kontor / We Refugees Archive.