The Arrival of Hannah Arendt

This film describes the arrival of Hannah Arendt - a Jewish, German-American political theorist and publicist - in New York and her reflections on flight and helping people start over.

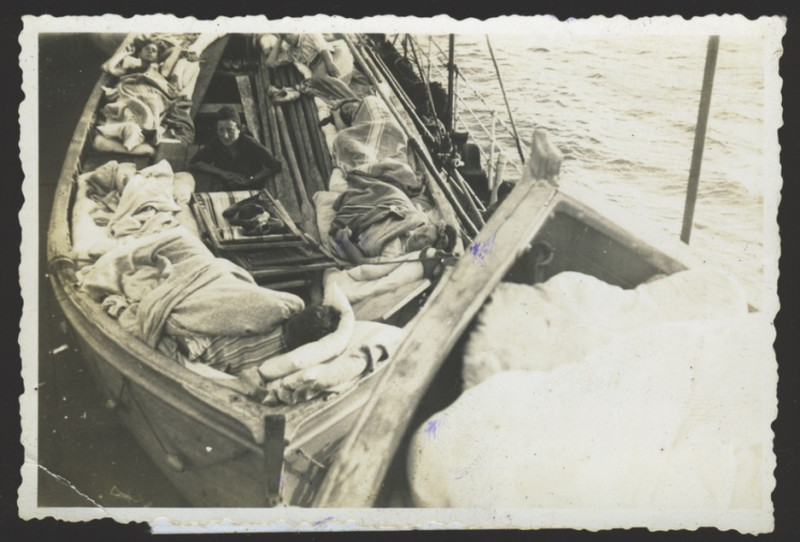

View of sleeping passengers on the crowded deck of the SS Navemar arriving in the United States, 1941. LBI Archives, SS Navemar, Saul Sperling Collection.

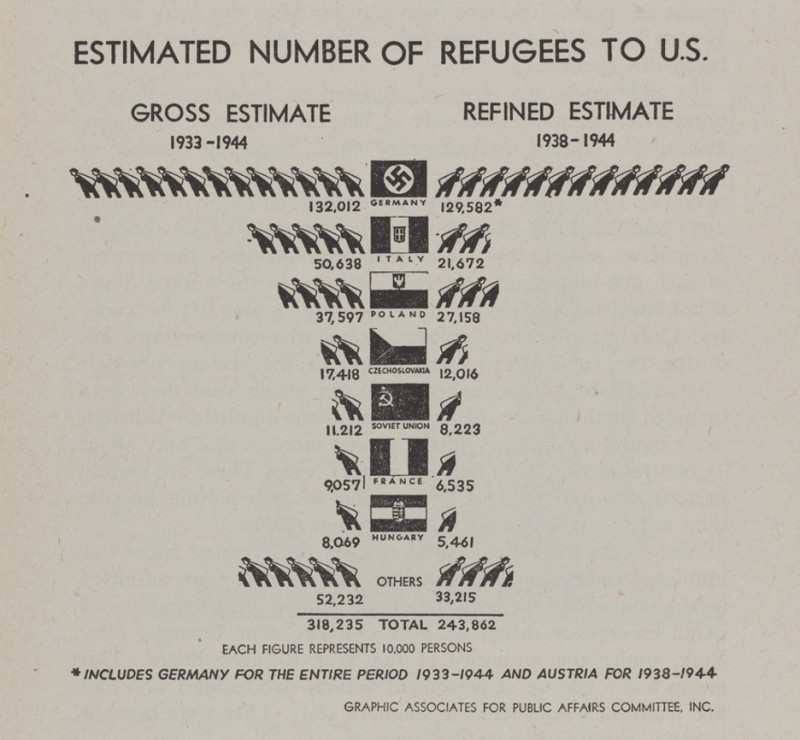

Graph showing the estimated number of refugees who came to the United States between 1933-45. From: The Refugees are Now Americans, New York Public Affairs Committee, 1945, LBI Library.

Skyline, 1947, New York, photographed by Fred Stein, with kind permission of Peter Stein © Fred Stein Archive

Shop Keeper, 1946, New York, photographed by Fred Stein, with kind permission of Peter Stein © Fred Stein Archive

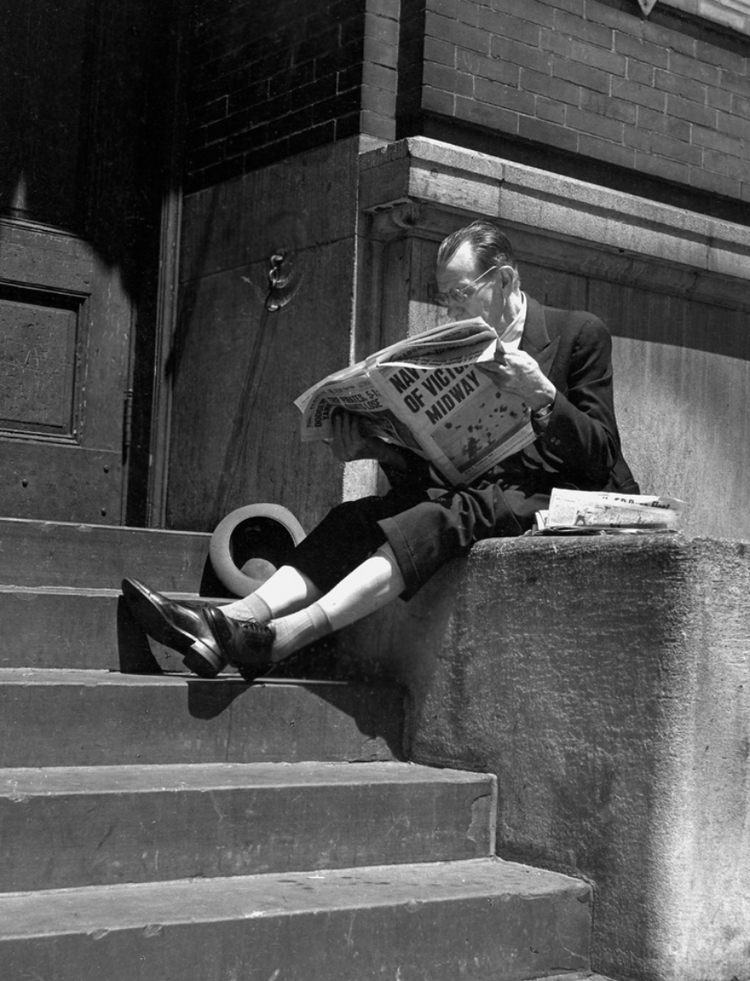

Man reads the Newspaper, 1942, New York, photographed by Fred Stein, with kind permission of Peter Stein © Fred Stein Archive

Italy Surrenders, 1943, New York, photographed by Fred Stein, with kind permission of Peter Stein © Fred Stein Archive

Frank Sinatra’s world-famous ode “New York, New York” tells the story of a vagabond who sets out to realize himself in his dream city: the dazzling, and also always quite scary, New York. Probably no other city in the world is as synonymous with migration and innovation as the metropolis on the Hudson: the Statue of Liberty, Ellis Island, the Lower East Side have, thanks to a never-sleeping culture industry, burned themselves into the general consciousness as synonyms for salvation and infinite freedom, new beginnings and the hunt for fulfillment of the eternally-unattainable American dream.

Indeed, a walk through the city even today reveals how different migrant groups shaped it. For centuries, new arrivals shaped New York and still inscribe themselves like sediments in its urban topography: China Town today overlaps with the former Jewish Lower East Side, Little India and Korea Town. Washington Heights was home to many German-Jewish Holocaust refugees and is today dominated by Puerto Rican migrants. That New York never meant a life of freedom and wealth for most of them is clear to many soon after their arrival. This was also the case for refugees to the United States, 90% of whom, according to estimates, arrived in the port of New York between 1933 and 1941 and remained here temporarily or long-term. Thus the German-Jewish exile Mascha Kaléko wrote desperately in her diary in the summer of 1941:

We are without money. Without friends. Without connections. Without hope. Carfare missing. Shoes missing. […] Damn money. […] A bank account is a good prevention against depression. […] We have never been so “refugees” as now. […] Organized welfare makes people irresponsible towards the suffering individual. They have paid their dues. Their conscience is clear. You die. Why are you not successful? Where success – only means money. 11Kaléko, Mascha, 1941: Diary entry, 20 June 1941. Partly published in: Zoch-Westphal, Gisela, 1987: Aus den sechs Leben der Mascha Kaléko. Berlin: Arani. Pp. 120-121. In the We Refugees Archive: https://en.we-refugees-archive.org/archive/mascha-kaleko-about-serious-material-concerns-as-a-refugee-in-new-york-1941/

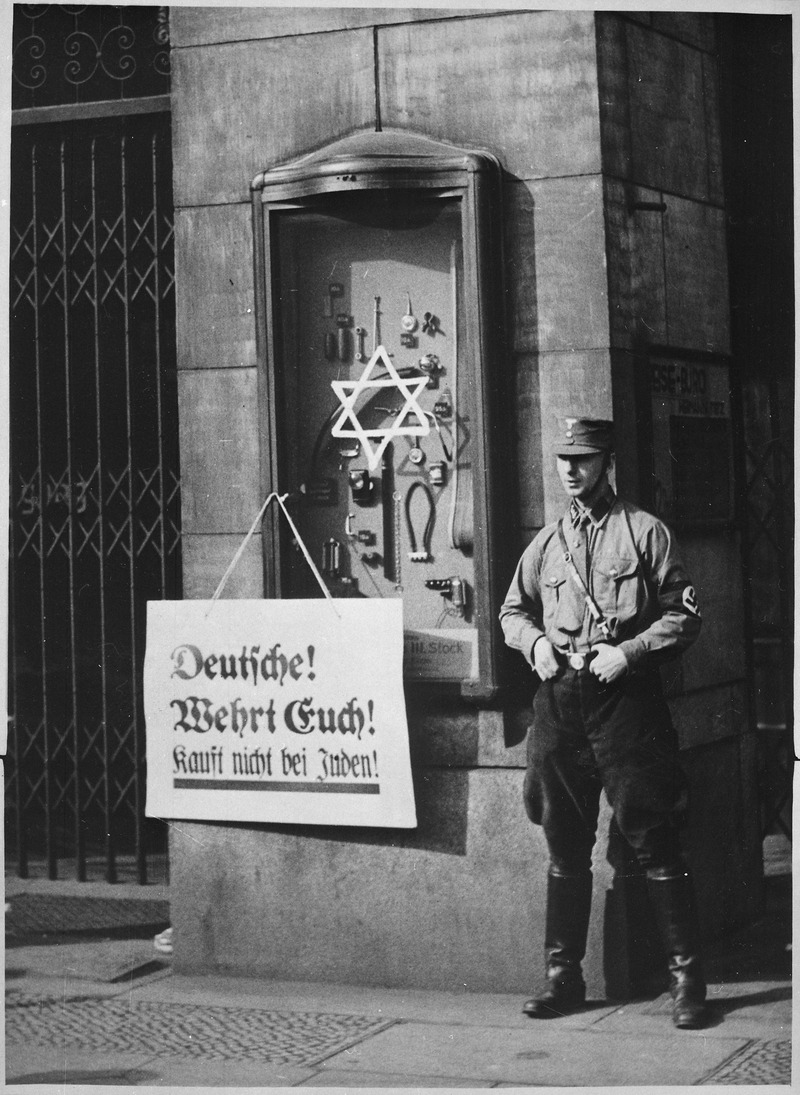

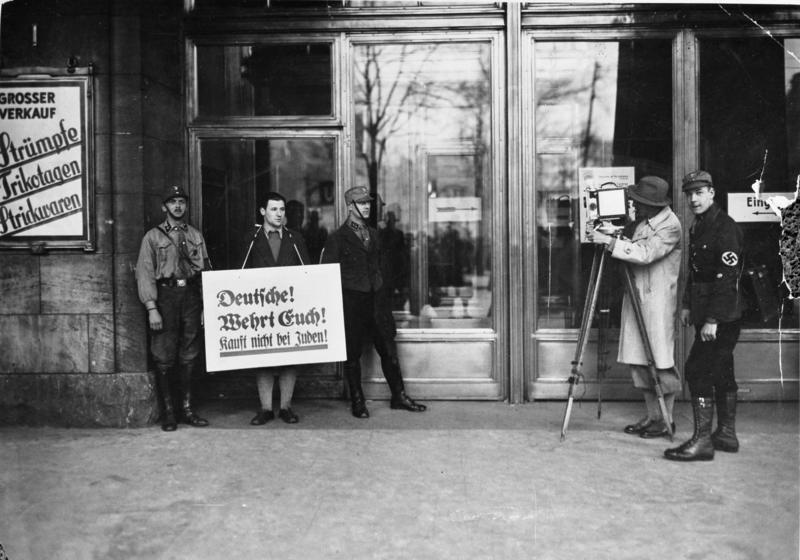

But contrary to the myth of New York as a welcoming melting pot, the history of migration in the 1930s and 1940s to the United States in general and to New York in particular shows that the city opened its doors to comparatively few, especially during this dark period when millions sought refuge from German fascism and Nazi persecution.

Many who sought a safe haven from persecution in the 1930s and 1940s failed because of the United States’ restrictive immigration quotas and complicated and demanding visa requirements. Between 1933 and 1941, for example, of the hundreds of thousands who sought asylum, only 110,000 Jewish refugees from Nazi-occupied territories found refuge in the United States. Non-Jewish refugees faced equally immense difficulties.

Fearing that immigrants, including those fleeing persecution, would compete for scarce jobs and strain public services in the midst of the Great Depression, most Americans opposed changing or adjusting the existing immigration law (the Johnson-Reed Act or National Origins Act, ratified in 1924) 33World War I and its aftermath decisively changed the political climate in the United States. Isolationism a la “America First” had its origins here. Coined by President Woodrow Wilson in 1916, it promised to keep the United States neutral in World War I and gained successive currency in the interwar period. Against this backdrop, as well as the influenza pandemic and the postwar economic recession, the U.S. House of Representatives voted in December 1920 to suspend immigration to the United States for one year. On May 19, 1921, President Warren Harding signed the Quota Act of 1921 (also known as the Emergency Quota Act), which allocated a certain number of visas per year to each country. Quotas of 1921 were still enforced at Ellis Island at the gates of New York at that time, not at U.S. consulates abroad, so the decision on entry was made only upon arrival in New York. The Immigration Act (also: Johnson-Reed Act or National Origins Act), passed in May 1924, was intended to create a more permanent immigration law. The act required that potential immigrants obtain U.S. immigrant visas at consulates abroad before entering the United States. The 1924 Act capped immigration quotas at 164,667 persons per year. The new quotas, inspired in part by American advocates of eugenics, favored “desirable” immigration from northern and western Europe. Immigrants from the Western Hemisphere who were needed as labor in the United States were exempt from the quota system. Immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe, which accounted for most recent immigration, was severely restricted. Many people born in Asia and Africa were barred from immigrating to the United States solely on racist grounds. Isolationism paired with racism, anti-Semitism, xenophobia. throughout the 1930s. This had been increasingly restrictive since the end of World War I. In the 1940s, refugees were additionally seen as a potential risk to national security. The general anti-immigrant sentiment in the country was also expressed in the policy of the State Department, which now viewed quotas as limits rather than goals and did not attempt to meet them. Between 1933 and 1941, for example, some 118,000 German quota places that could have been used were not. Even after the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany and the 1938 pogrom night, the U.S. legal situation did not change. In June 1938, 139,163 persons were on the waiting list for the German contingent. A year later, in June 1939, the waiting list had grown to 309,782 persons.

In July 1941, coinciding with Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union and the extreme radicalization of German extermination policies, not only were all U.S. consulates in Nazi-occupied territories closed, but all visa control for foreigners was centralized in Washington. Visa applications were submitted to an interagency review board composed of representatives from the Visa Division, the Immigration and Naturalization Service, the FBI, the Military Intelligence Division of the War Department, and the Office of Naval Intelligence of the Navy Department.

Potential applicants first registered with the consulate and were then placed on a waiting list. During this time, they were able to assemble all the documents necessary for the issuance of a visa, including identity papers, police certificates, exit and transit permits, and affidavits about their finances. After the war began, the requirements were further increased: Applicants were now required to submit two affidavits of their financial circumstances instead of one, as well as moral declarations from several impartial persons attesting to their identity and good conduct. An American sponsor had to be found who had the financial means to ensure that one would not be a burden to the state. For many immigrants, this was the most difficult part of the American visa process. They also had to show a valid ship ticket before they could obtain a visa. However, with the outbreak of war and fears that German submarines would attack passenger ships, shipping across the Atlantic became extremely risky and drastically reduced. The increased bureaucracy combined with the lack of access to American consulates and lack of shipping beginning in 1941 spelled the end for many of their hopes of immigrating to the United States. Additionally, the State Department canceled waiting lists as the United States entered World War II in December 1941.

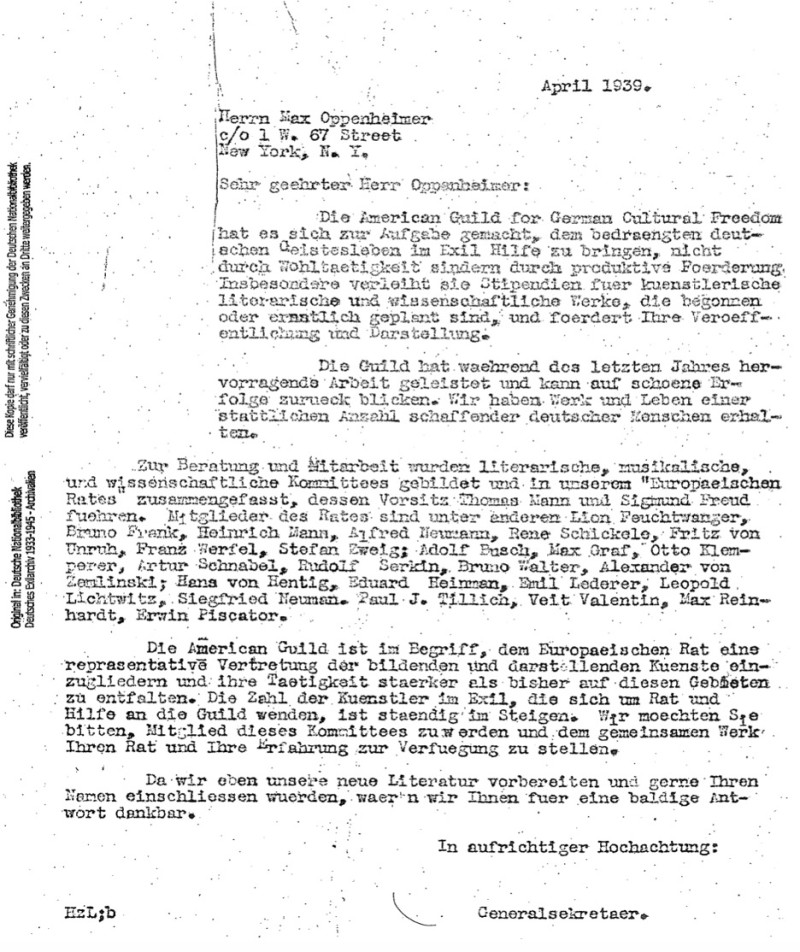

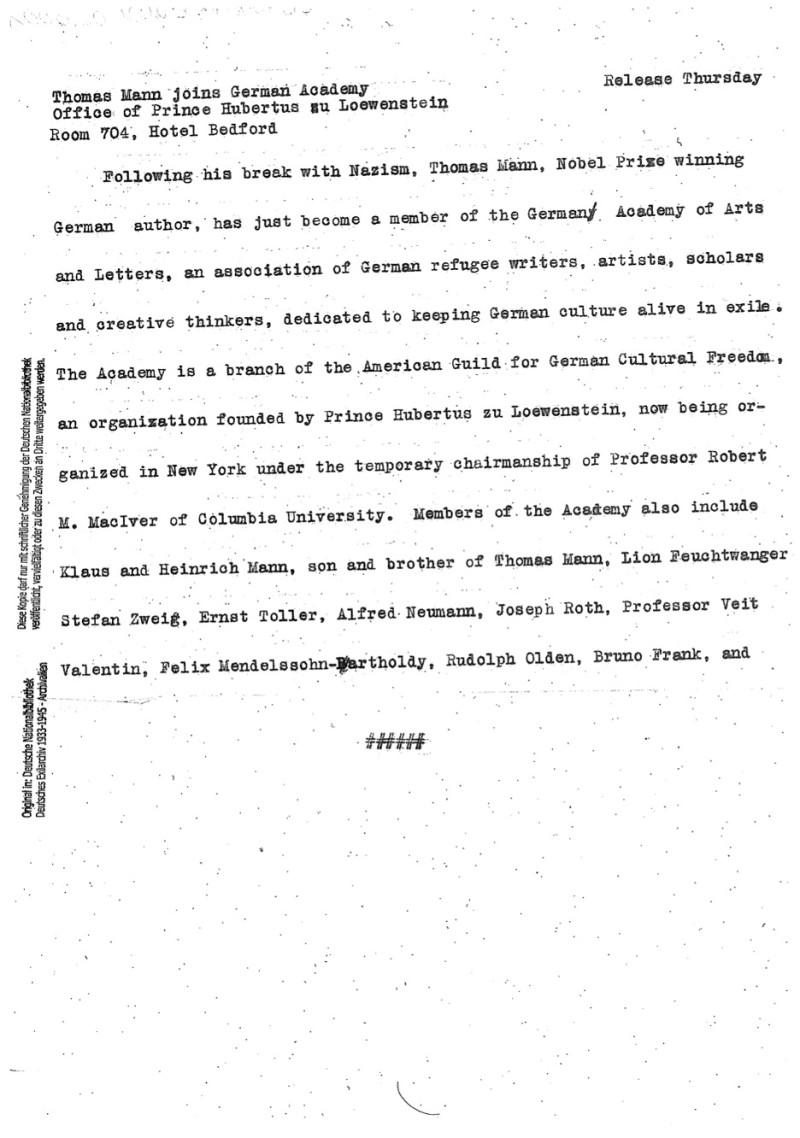

Despite widespread opposition to migration, as well as increasing bureaucratic hurdles from the government, private individuals and relief organizations, such as the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS), the National Refugee Service, the Emergency Rescue Committee, JDC, the American Guild for German Cultural Freedom, among others, became involved to help thousands of refugees with funds for food and clothing, transportation, employment, and financial assistance, as well as help in finding affidavits for potential immigrants without family in the United States. These private organizations enabled thousands to escape. In the 1939 quota year, after all, the German quota was fully met for the first time since 1930: 27,370 persons received visas. In the quota year 1940, 27,355 persons received visas, but these figures were far below the number seeking protection.

A vivid example of the consequences of the restrictive U.S. migration regime is the St. Louis tragedy. In May/June 1939, the United States denied entry to over 900 Jewish refugees who had come from Hamburg on the St. Louis. The ship appeared off the coast of Florida shortly after Cuban authorities canceled the refugees’ transit visas and denied entry to most of the passengers, who were still waiting for their visas to the United States. Denied permission to land in the United States, the St. Louis was forced to return to Europe. The governments of Great Britain, France, the Netherlands, and Belgium agreed to take on only some of the passengers inside. Of the total 908 passengers, 254 (almost 28%) perished in the Holocaust. 33Sarah A. Ogilvie, Refuge denied : the St. Louis passengers and the Holocaust. Madison, Wis. : University of Wisconsin Press. 2006.

According to a rough estimate by the New York Public Affairs Committee, a total of 318,235 fugitives reached the United States in the period from 1933 to 1944, of whom over one-third came from Germany, followed by over 50,000 people from Italy and over 35,000 from Poland and other European countries occupied by Germany. Many of them stayed in New York City temporarily or long-term, such as about 20,000 of the total of about 125,000 German-speaking Jewish refugees from Germany and Austria who settled in New York’s Washington Heights neighborhood. They all found a city marked by the Great Depression, the severe economic crisis.

In addition to German-speaking Jews, thousands of non-Jewish Germans came to New York, as well as Jewish and non-Jewish Poles, Italians, Czechoslovakians, French, Hungarians, and refugees from the Soviet Union. 44In 1939-1940, more than 50% of all immigrants to the United States identified themselves as Jewish, but the actual number is probably higher, as refugees tended to check off another “national” category, such as “German” instead of the racializing category “Hebrew,” or did not define themselves as Jewish even when the Nazis did. Thus, between 1938 and 1941, a total of 123,868 self-identified Jewish refugees immigrated to the United States. But German-speaking Jewish immigration to New York in the 1930s and 1940s has been by far the best researched and will be the focus here as well. 55Research includes: Loro Gemeiner Bihler, Cities of Refuge: German Jews in London and New York, 1935-1945 (Albany: SUNY Press, 2018); Thomas Hartwig and Achim Roscher, The Promised City: German-Jewish Emigrants in New York: Conversations, Impressions, and Images (Berlin: Das Arsenal, 1986); Claudia Appelius, “Die schönste Stadt der Welt: German-Jewish Refugees in New York (Essen: Klartext, 2003); Henri Jacob Hempel, ed, “If I Must Be a Stranger…”: German Jewish Emigrants in New York (Frankfurt/Main: Ullstein Sachbuch, 1983); Gloria DeVidas Kirchheimer & Manfred Kirchheimer, We Were So Beloved: Autobiography of a German Jewish Community (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1997); Gerhard Falk, The German Jews in America : a minority within a minority (Lanham: University Press of America, 2014).

For Eastern European Jewish refugees, so-called Landsmanshaftn – associations for people from certain Eastern European hometowns – or political organizations that, like the General Jewish Workers’ Federation, also shifted their work from Europe to the American continent due to the war, served as the first point of contact, especially on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. A relatively large number of Jewish and non-Jewish academics, such as the representatives of the Frankfurt School, found a new home at New York universities such as Columbia University. 77Simone Lässig, “Strategies and Mechanisms of Scholar Rescue: The Intellectual Migration of the 1930s Reconsidered,” Social Research: An International Quarterly 84:4 (Winter 2017): 769-807; Joanna Vecchiarelli Scott, “Alien Nation: Hannah Arendt, the German Emigrés and America,” European Journal of Political Theory 3:2 (2004): 167-176. More affluent refugees from Berlin and the northern regions of Germany gravitated to the Upper West Side in Manhattan and the neighboring borough of Queens on the east side of the East River, while those from southern Germany and more rural regions, who were increasingly members of the former German middle class, preferred Washington Heights on the upper tip of Manhattan between Inwood to the north and Harlem to the south. Choice of residence always has to do with social class, and those who had relatives or friends in New York may have had housing to begin with; others were supported by (Jewish) aid organizations and housed in temporary shelters that were often overcrowded and cold.

Some of them are housed temporarily in the “Congress Houses” or other shelters maintained by charitable organizations, many of which are situated in midtown or downtown Manhattan near the docks. Here they are taken care of without cost over a period of four weeks, until they can find some place to go and other means of support. Since all guests in the houses are refugees, the atmosphere is distinctly European, and a part of the old homeland reaches into the new life. 88Gerhart Saenger, Today’s Refugees, Tomorrow’s Citizens: A Story of Americanization (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1941), 67. Übersetzung aus dem Englischen: We Refugees Archiv.

Some German-speaking Jewish refugees arrived eager to take a second chance in America. Once part of the German middle class and holding professional positions, many took manual jobs for the time being despite being overqualified, or had to acquire new American qualifications in order to work. Many women entered the workforce for the first time, and others faced open anti-Semitism in their job search.

I believe the real heroes of the early struggles for an economic foothold were the women – all the more remarkable since most of them came from a middle-class milieu where wives or grown daughters adorned and possibly organized the hoursehold but did not do household chores, and where education had prepared relatively few for professional or semi-professional work. The ladies hired themselves out as domestics, cooks, governesses, kindergarten assistants, sales clerks, or used the skills acquired in Hitler Germany to run bakeries or lampshade workshops, or sold Avon products door-to-door while the men were seeking ways to enter the system. And they were doing so without loss of dignity and in the conviction that this way only a temporary expedient, so it involved no sense of social degradation. 99Leo Grebler, German-Jewish Immigrants to the United States during the Hitler Period: Personal Reminiscences and General Observations, YIVO (1976), 84.

Still others were exhausted and worn down by months, even years, of persecution. A loss of home, community, friendships, work, social status, and way of life probably united them all, so connecting with people from home, maintaining traditions, and cultivating the German language was a priority for many. Some even had their furniture sent from Germany.

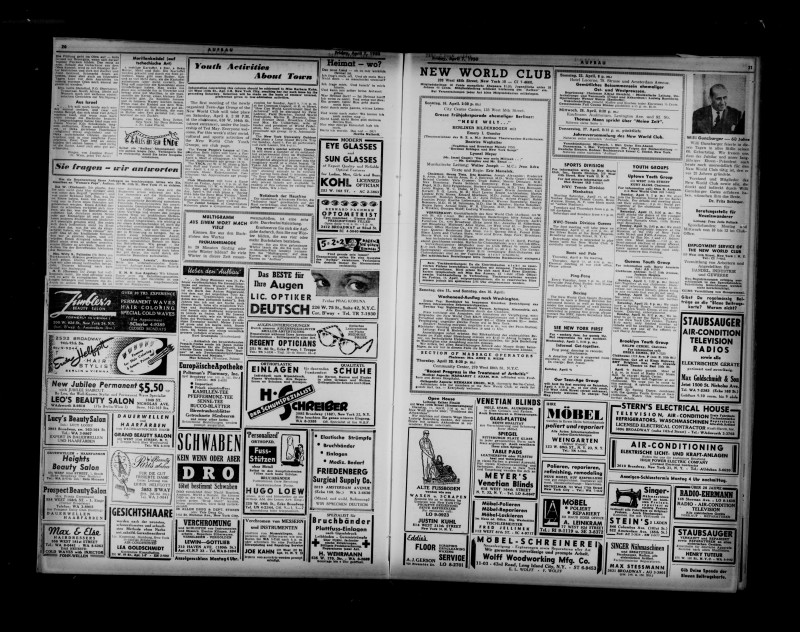

In the Heights, people encountered familiar names and faces, German-speaking stores and clubs, and Jewish institutions founded by people of Eastern European descent who had made their way uptown in the years before. As in all the other cities covered by We Refugees Archive, learning and mastering English was one of the most pressing issues for immigrants and refugees arriving in New York. It determined job prospects, social life, status, housing, and neighborhoods. Speaking German conspicuously in public was fraught with the stigma of provinciality, but the older generation of refugees in particular clung to German even in public and was able to do so in the Heights’ cabarets, cafés, social clubs, and sports teams. The increasingly established religious communities and educational institutions were also important networking structures.

The Allied victory ended Nazi terror in Europe in May 1945 and the war in the Pacific in August. Six million European Jews had been murdered. Hundreds of thousands of survivors, suffering from hunger and disease, came out of concentration camps, hiding places, and temporary shelters to find a world that still seemed to have no place for them. For refugees themselves who had made it to the United States before 1945, the commitment to their new homeland became even greater with the end of World War II, the brutal disappearance of Jewish communities in Europe, and the obvious fragility of life in Palestine. To those who had served the U.S. in the war, returning to New York took on new meaning. Those who had once envisioned an eventual return to Europe mostly settled permanently in New York and became U.S. citizens in the 1940s.

Life in New York became easier in many ways. The newcomers had a better command of the English language, their careers were more established, the job market was more promising, and the fruits of the New Deal 1010The New Deal was a series of economic and social reforms enforced between 1933 and 1938 under U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in response to the Great Depression were evident. Following this description of German Jewish refugees, it seems indeed that, to conclude with Sinatra, “small town blues” melted away as they made “a brand new start in old New York.” But what Sinatra also emphasizes is that it is “up to you, New York, New York,” that is, the American migration regime, the political-economic situation, and the social situatedness in which refugees come to the city to build a new life and find a future.

This film describes the arrival of Hannah Arendt - a Jewish, German-American political theorist and publicist - in New York and her reflections on flight and helping people start over.

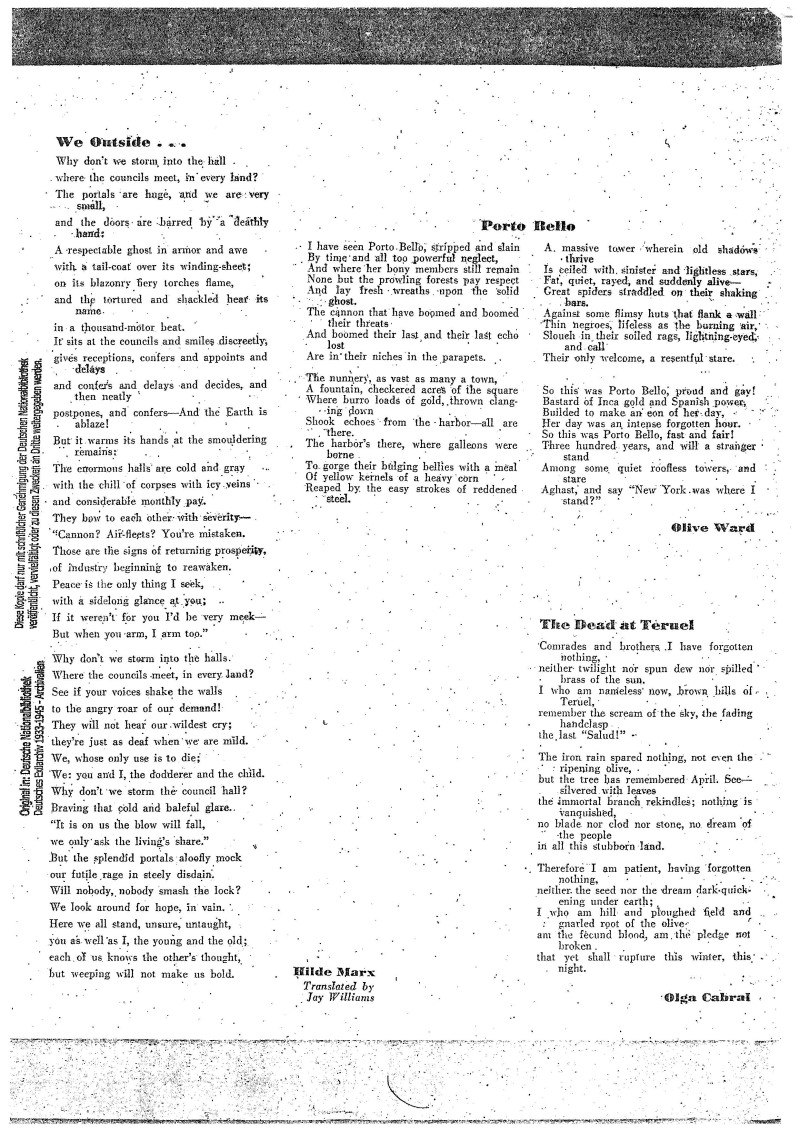

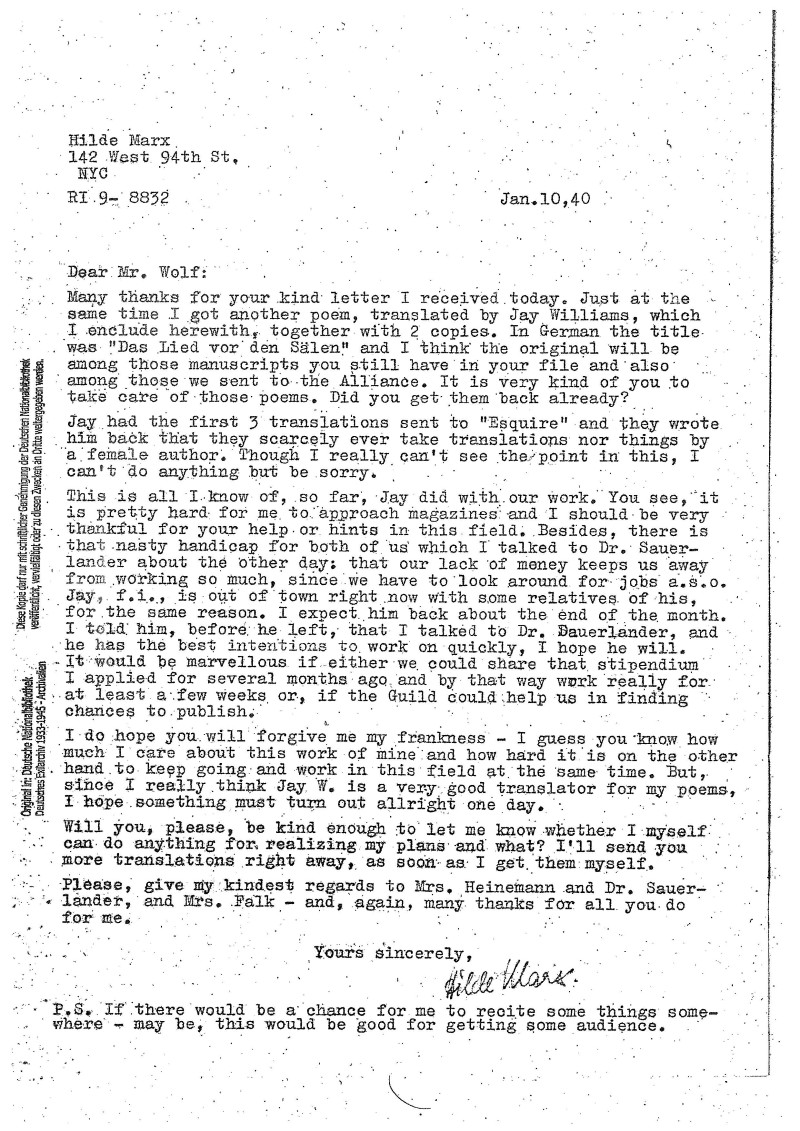

Hilde Marx (1911-1986) was a German-American poet, writer and journalist. She is one of the authors whose writing career was only just beginning when…

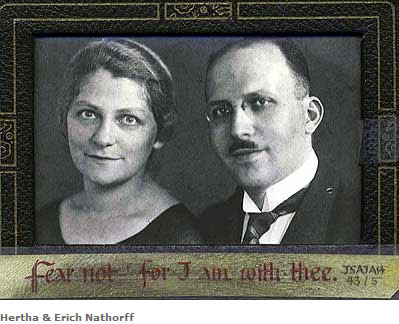

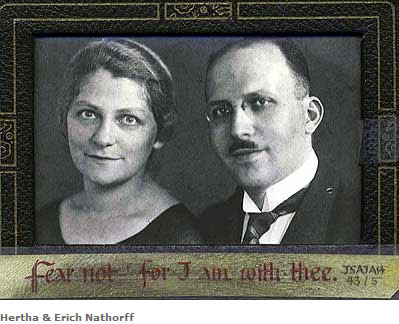

Hertha Nathorff, née Einstein (1895-1993) was a German pediatrician, psychotherapist and social worker. Until 1934 she worked as a senior physician at the Red…

Austrian painter Max Oppenheimer (1885–1954) is asked to join the visual and performing arts committee established by the Secretary General of the Council of…

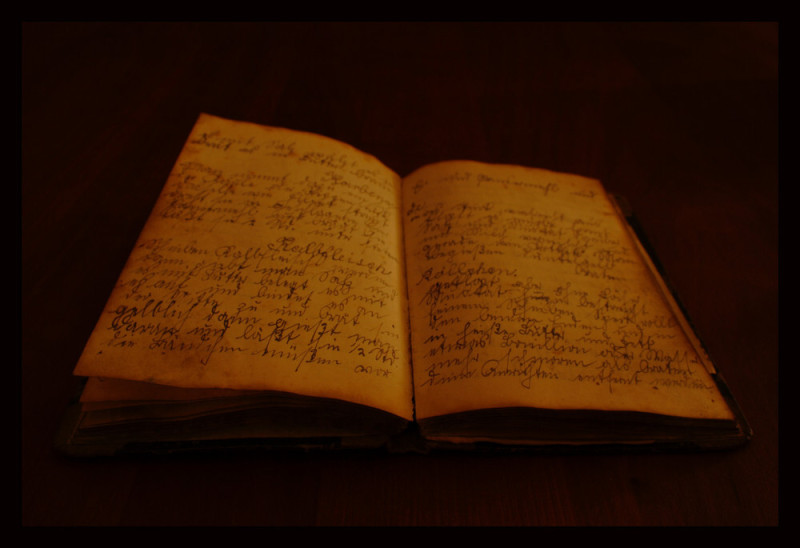

In excerpts from the diary Berlin-New York Aufzeichnungen 1933 bis 1945, Hertha Nathorff describes her inconceivable displacement from her homeland and the destruction of…

Fred (Fritz) Grubel (in Germany formerly Grüber) worked in the administration of the Jewish Community in Leipzig, his responsibilities included organizing the emigration of…

In her work “A Jewish Refugee in New York” Kadya Molodowsky presents the life of the twenty-year-old refugee from Lublin Rivke Zilberg in New…

Helga Hagen was born in 1918 in Berlin-Nikolassee. The father, a private banker, comes from the bourgeois, completely assimilated Jewish upper class of the…

In excerpts from the diary Berlin-New York Aufzeichnungen 1933 bis 1945, Hertha Nathorff vividly describes the destruction of her life, which was incomprehensible to…

Hilda Epstein was a German nurse born in Karlsruhe into a religious Jewish family. She learned infant care in Heidelberg, and later moved to…

Oskar Maria Graf was a German-American writer. His literary beginnings can be found in expressionist poetry. He wrote poems, novels, (autobiographical) stories, calendar stories,…

Hertha Nathorff, née Einstein (1895-1993) was a German pediatrician, psychotherapist and social worker. Until 1934 she worked as a senior physician at the Red…

In her work “A Jewish Refugee in New York” Kadya Molodowsky presents the life of the twenty-year-old refugee from Lublin- Rivke Zilberg in New…

Hilde Marx (1911-1986) was a German-American poet, writer and journalist. She is one of the authors whose writing career was only just beginning when…

A couple of months after her flight to New York, the poet Mascha Kaléko (1907-1975) describes her first impressions of the city in a…

In her work “A Jewish Refugee in New York” Kadya Molodowsky presents the life of the twenty-year-old refugee from Lublin Rivke Zilberg in New…

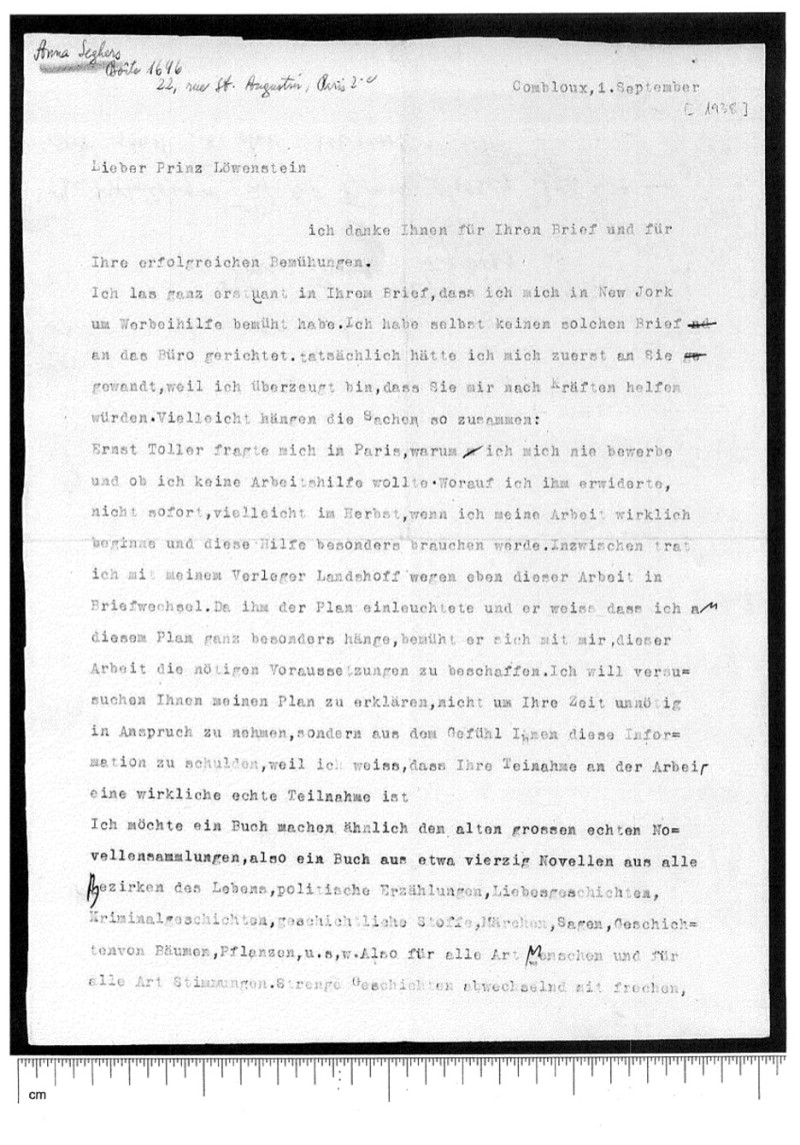

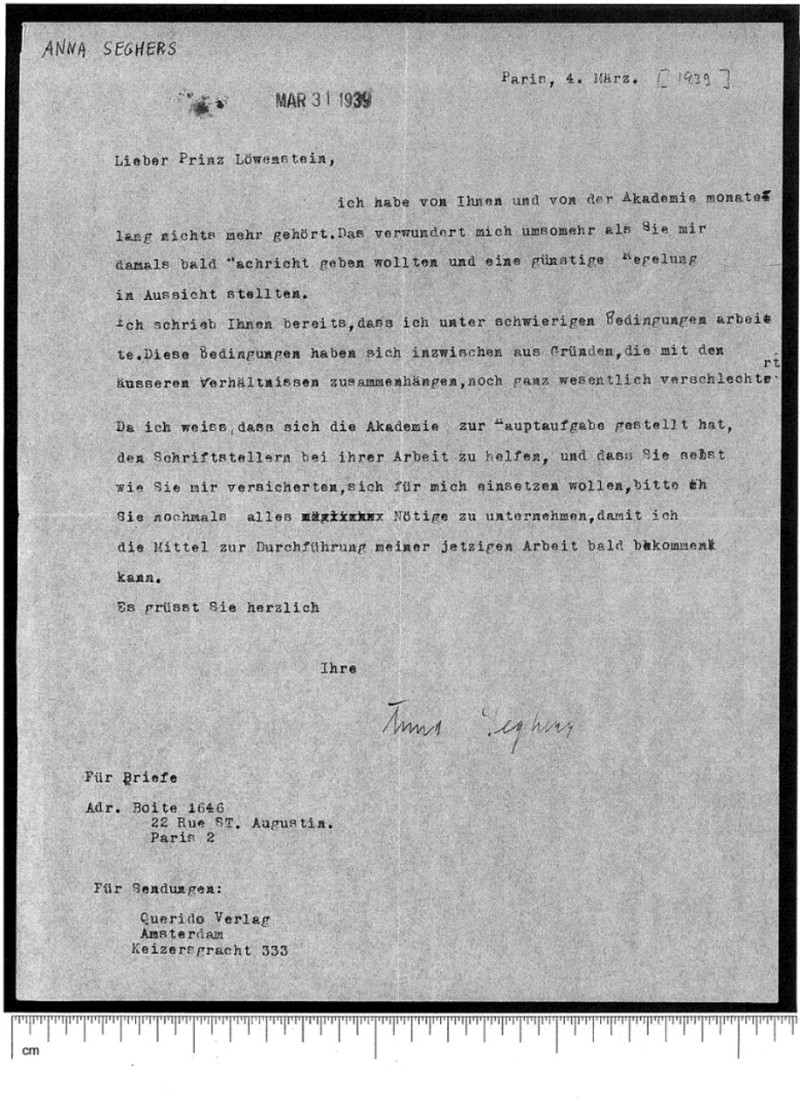

In this letter from September 1938 Anna Seghers thanks Prince Löwenstein for his help and explains how she plans to write her next book.

In her work “A Jewish Refugee in New York” Kadya Molodowsky presents the life of the twenty-year-old refugee from Lublin – Rivke Zilberg in…

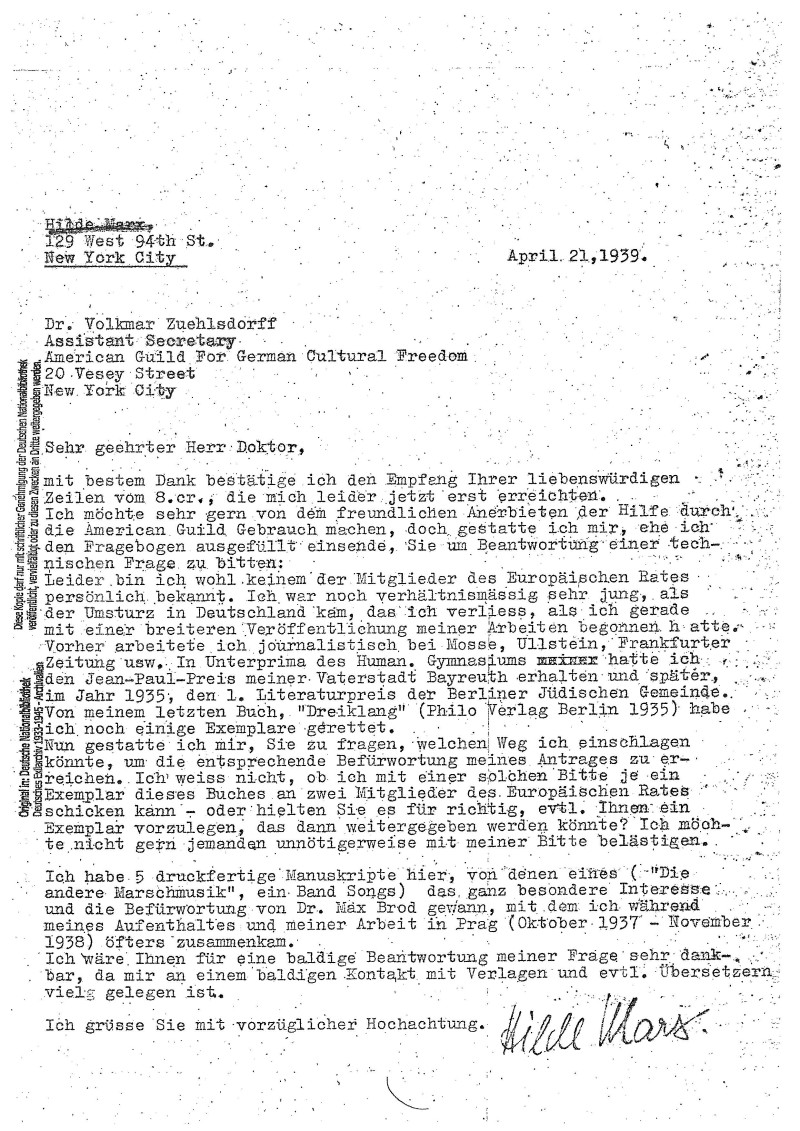

Hilde Marx (1911-1986) was a German-American poet, writer and journalist. She is one of the authors whose writing career was only just beginning when…

In excerpts from the diary Berlin-New York Aufzeichnungen 1933 bis 1945 Hertha Nathorff vividly describes the expulsion from her homeland, which was incomprehensible to…

In excerpts from the diary Berlin-New York Aufzeichnungen 1933 bis 1945, Hertha Nathorff vividly describes the destruction of her life, which was incomprehensible to…

Poem by Mascha Kaléko (ca. 1938)

In excerpts from the diary Berlin-New York Aufzeichnungen 1933 bis 1945 Hertha Nathorff vividly describes the expulsion from her homeland, which was incomprehensible to…

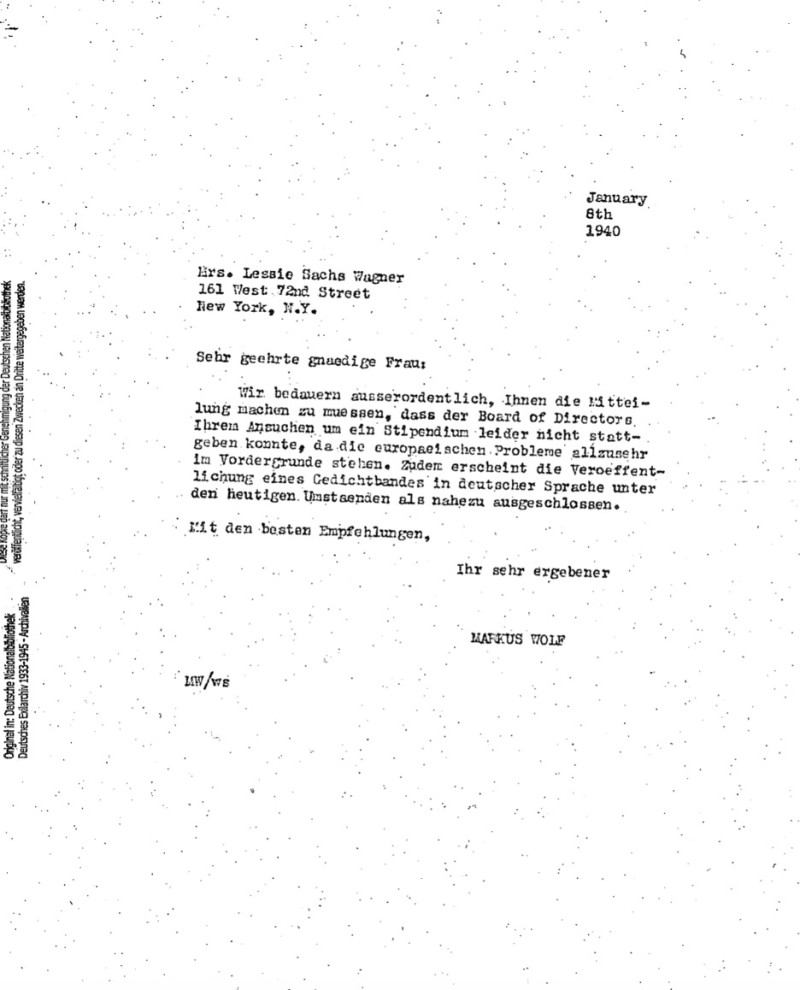

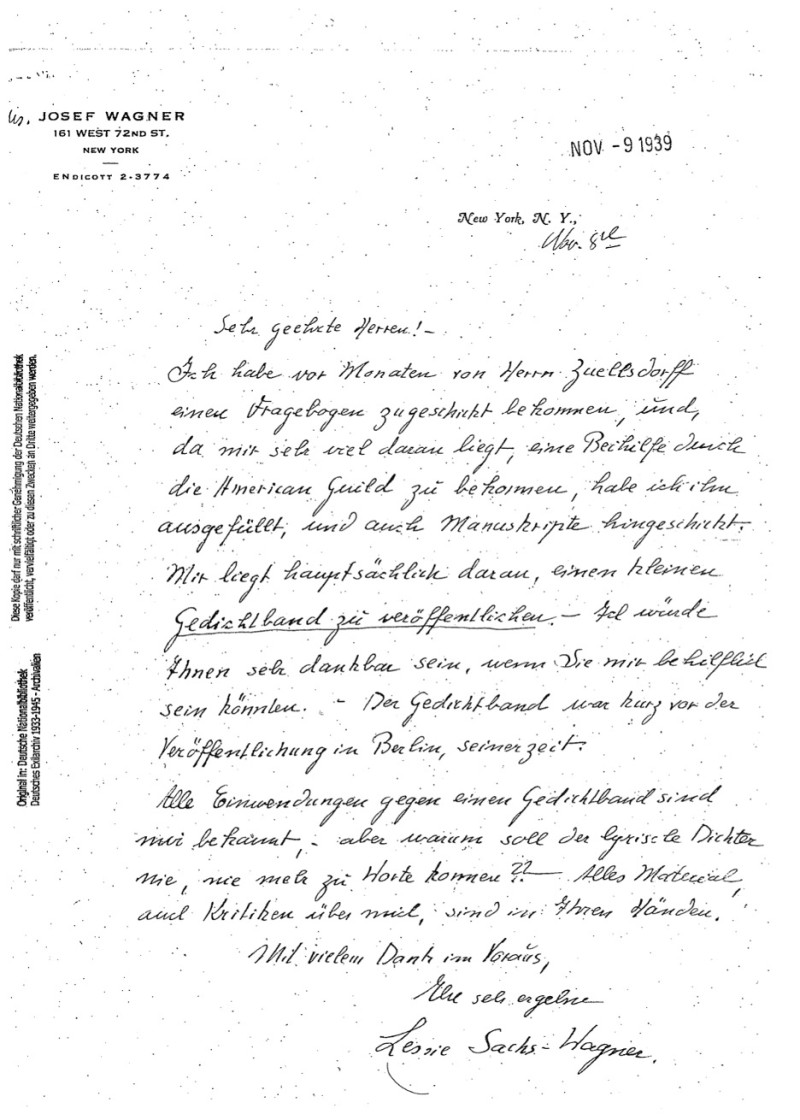

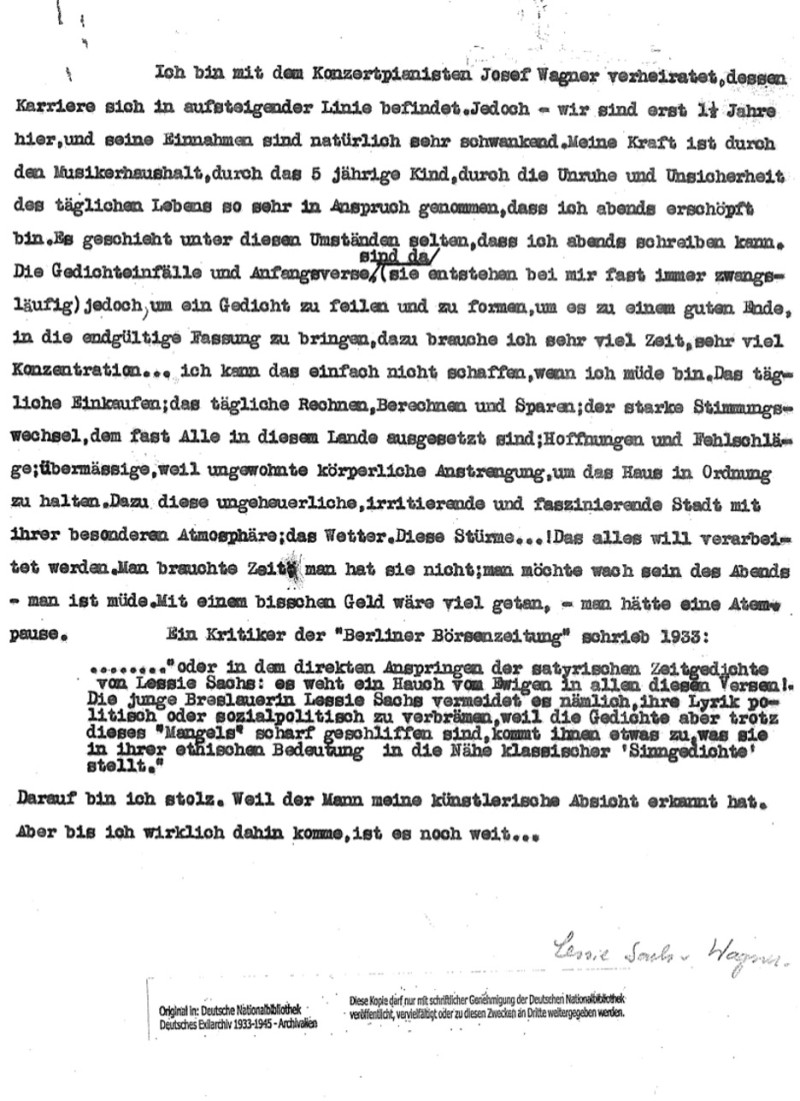

Lessie Sachs Wagner has applied for financial aid from the American Guild for German Cultural Freedom and in this letter she is denied her…

Poem by Mascha Kaléko

In an interview with Sender Freies Berlin on 1 June 1956, the poet Mascha Kaléko (1907-1975) looks back on her first years of emigration…

Hilde Marx (born November 1, 1911 in Bayreuth) was a German-American poet, writer and journalist. She is one of the authors whose writing career…

This is one of the crucial excerpts from Hannah Arendt’s essay “We Refugees” that she published in 1943 shortly after arriving in New York.

In the course of the National Socialist racial policy, Hertha Nathorff lost her license to practice medicine in 1934 and her medical license in…

As part of her year-long efforts to obtain material restitution for her persecution by Nazi Germany, the poet Mascha Kaléko (1907-1975) described her attempts…

Fred (Fritz) Grubel (formerly Grübel in Germany) was born in Leipzig in 1908. He studied in Leipzig,Frankfurt and received a doctorate in law. He…

The author of the novel “A Jewish Refugee in New York” Kadya Molodovsky is one of the most important Yiddish poets of the mid-20th…

Hilda Epstein was a German nurse born in Karlsruhe into a religious Jewish family. She learned infant care in Heidelberg, and later moved to…

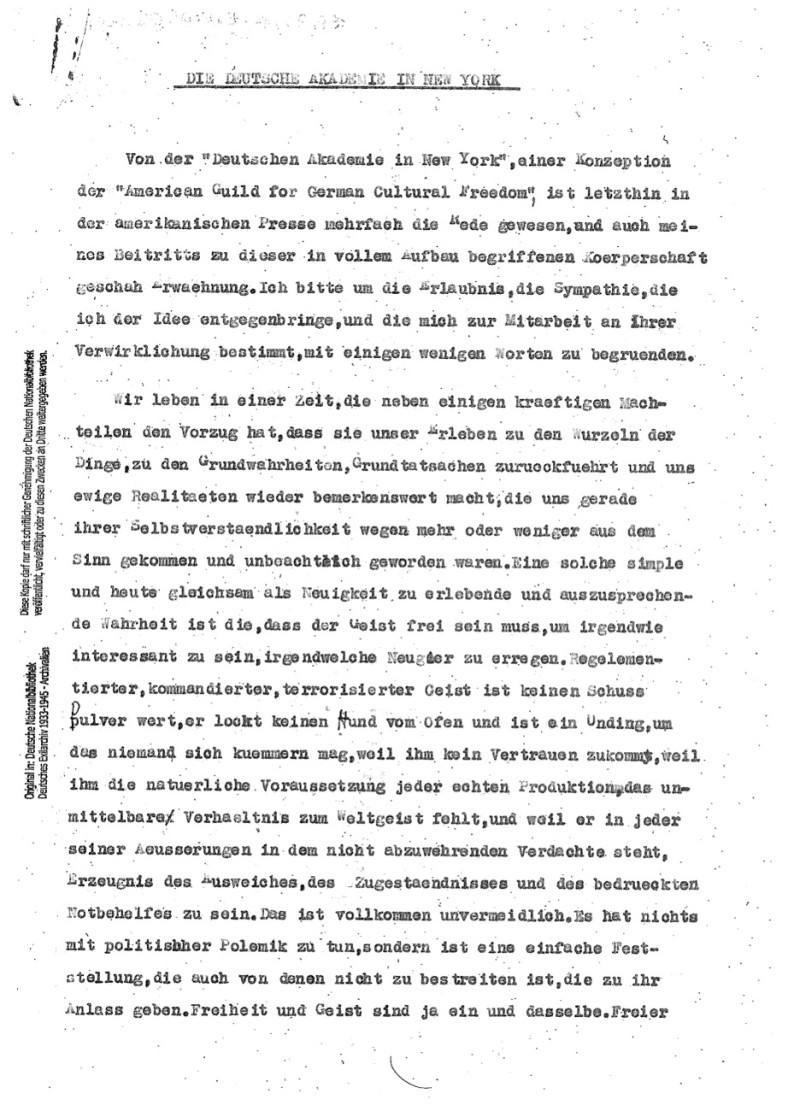

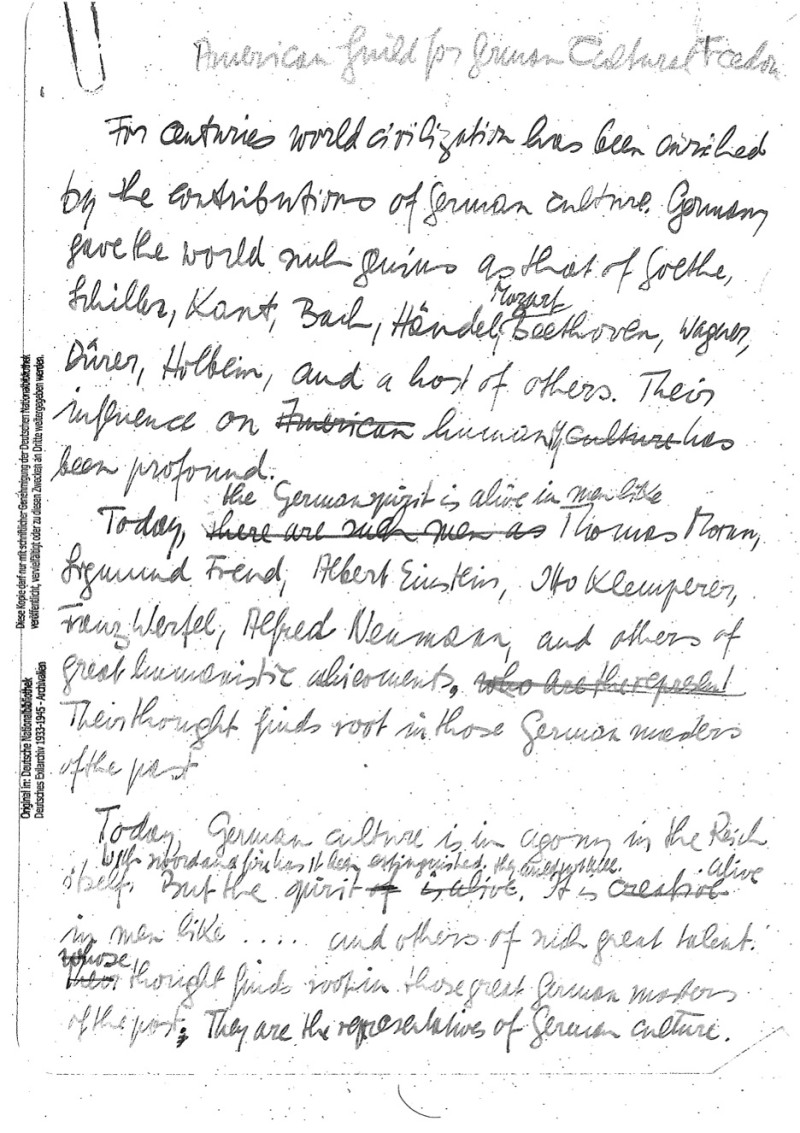

In this text, written by Thomas Mann (1875-1955), he explains his opinion about the foundation of the German Academy in New York in connection…

Hilde Marx (born November 1, 1911 in Bayreuth) was a German-American poet, writer and journalist. She is one of the authors whose writing career…

In a diary entry from September 1939, the poet Mascha Kaléko (1907-1975) reflects on the outbreak of the war in Europe and her own…

In this letter to her ex-husband Günther Anders from May 1941, Hannah Arendt gives an overview of her arrival experience in New York.

In a diary entry of 27 January 1939, the poet Mascha Kaléko (1907-1975) traces her escape from Germany to New York in the autumn…

Hilde Marx (1911-1986) was a German-American poet, writer and journalist. She is one of the authors whose writing career was only just beginning when…

Hilde Marx (born November 1, 1911 in Bayreuth) was a German-American poet, writer and journalist. She is one of the authors whose writing career…

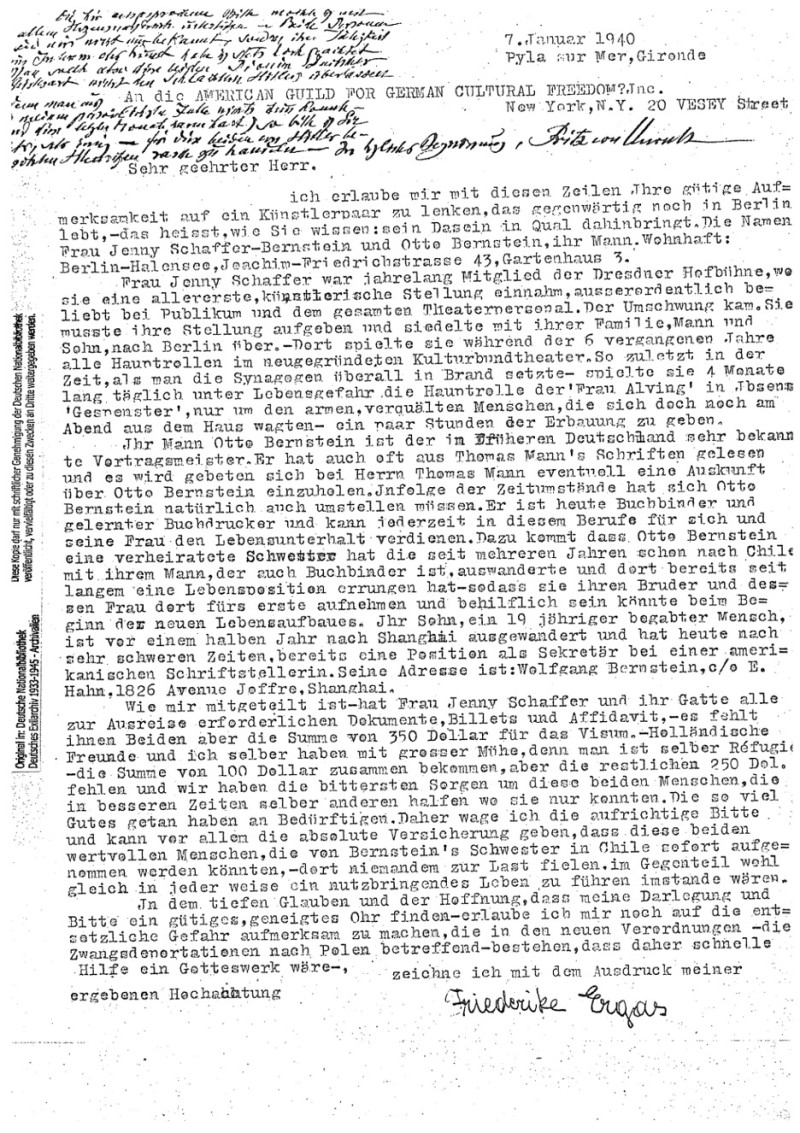

In this letter Friederike Ergas describes the living situation of her friends Jenny Schaffer Bernstein and Otto Bernstein who urgently need financial support from…

Bertolt Brecht’s poem on the difference between emigration and exile

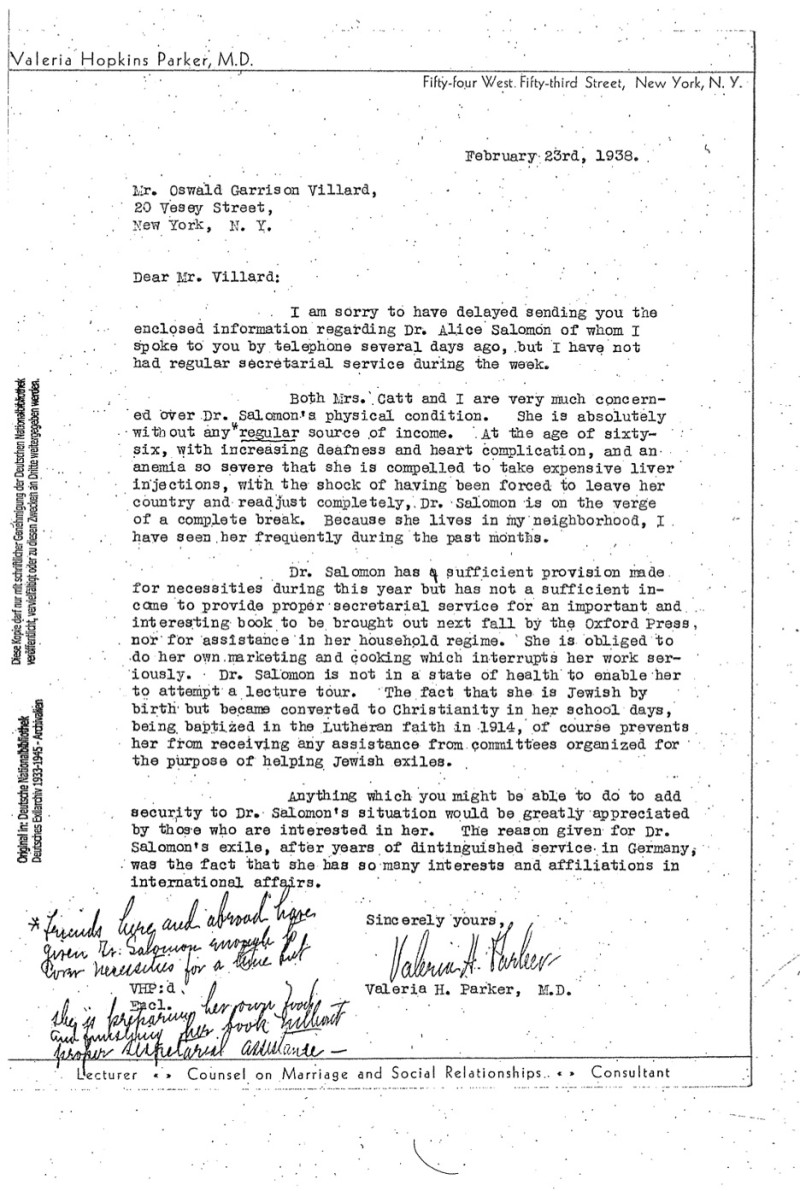

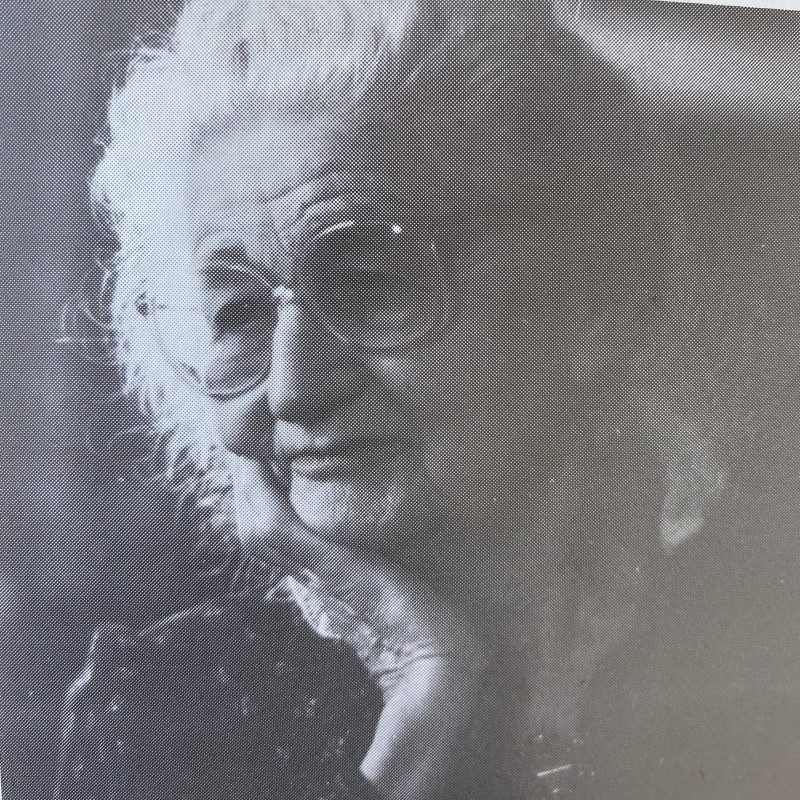

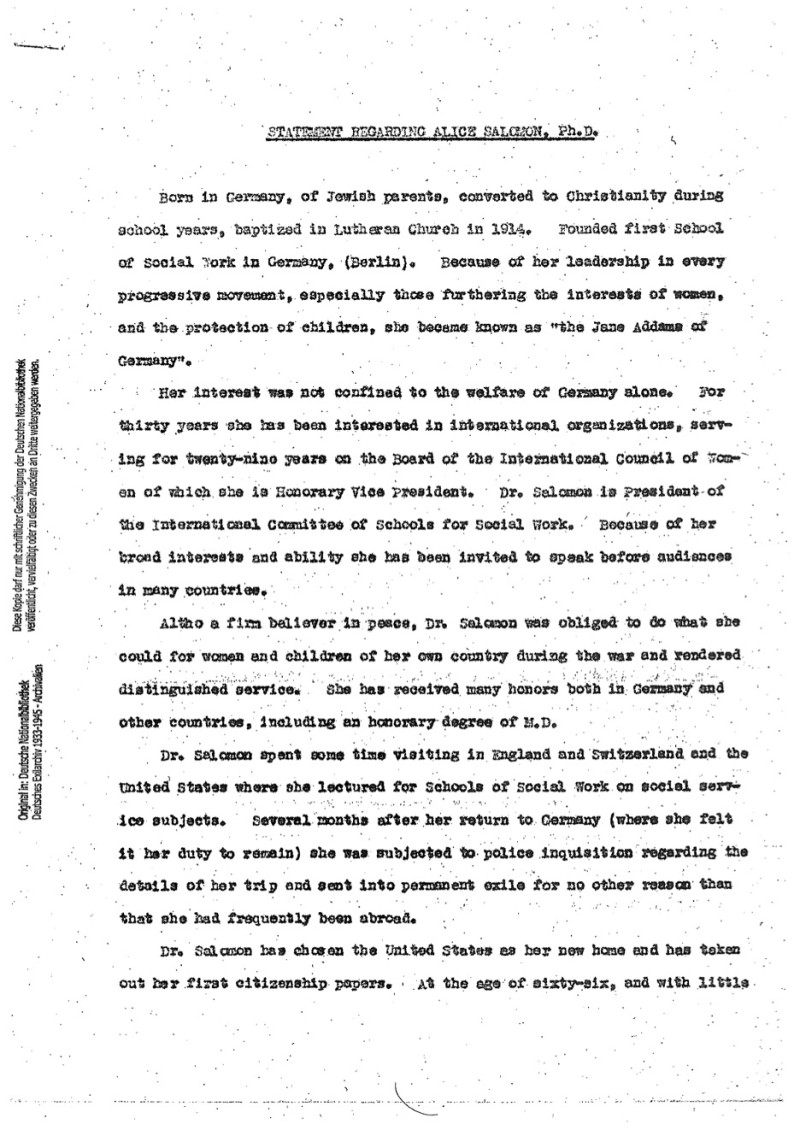

Valeria H. Parker is vouching for Dr. Alice Salomon (1872-1948) to get financial aid from the American Guild for German Cultural Freedom. She describes…

Leo Glueckselig was born in 1914 in Vienna, in the 2nd district. In 1938, immediately after the “Anschluss” of Austria to the Reich, Glueckselig…

Lessie Sachs Wagner (1872-1942) writes a letter to the American Guild for German Cultural Freedom to ask if they have decided to support her…

This document is a text about the admission of Thomas Mann (1875-1955) to the German Academy of Arts and Literature, which is part of…

Hannah Arendt tells her ex-husband Günther Anders about the circumstances of her escape from Lisbon and her arrival in New York.

In this letter Anna Seghers asks Prince Löwenstein why he has not gotten back to her, even though he said that he would get…

In excerpts from the diary Berlin-New York Aufzeichnungen 1933 bis 1945, Hertha Nathorff vividly describes the destruction of her life and the expulsion from…

In this excerpt, Hertha describes how she was forced to leave her job as head doctor of the Women’s and Counseling Center.

Hilde Marx (1911-1986) was a German-American poet, writer and journalist. She is one of the authors whose writing career was only just beginning when…

Else Pappenheim was an Austrian-American physician born in 1911 in Vienna to a Jewish family. She left Vienna in 1938 after the revocation of…

Alice Salomon’s life is described in this statement and the reasons she requires financial assistance from the American Guild for Cultural Freedom. The statement…

Poem by Mascha Kaléko, written in Israel in 1960’s

In excerpts from the diary Berlin-New York Aufzeichnungen 1933 bis 1945, Hertha Nathorff vividly describes the expulsion from her homeland, which was incomprehensible to…

IIn excerpts from the diary Berlin-New York Aufzeichnungen 1933 bis 1945, Hertha Nathorff vividly describes the expulsion from her homeland, which was incomprehensible to…

Käthe Berl was a well-known Austrian-American artist born in 1908 in Vienna into a Jewish family. Her family did not survive the Holocaust. Käthe,…

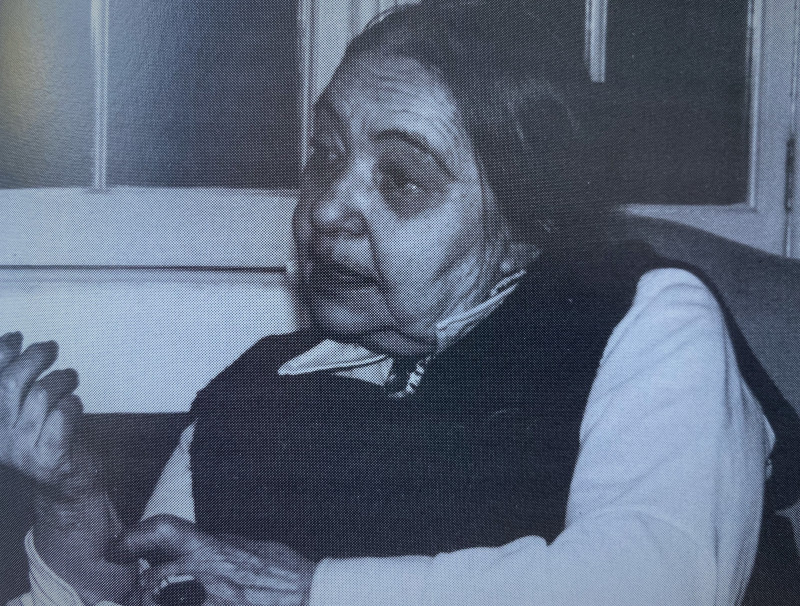

Hertha Nathorff, née Einstein (1895-1993) was a German pediatrician, psychotherapist and social worker. With the help of American relatives, she managed to emigrate to…

In this letter, Lessie Sachs Wagner describes her current living situation and the difficulty of finding time to focus on her work. She is…

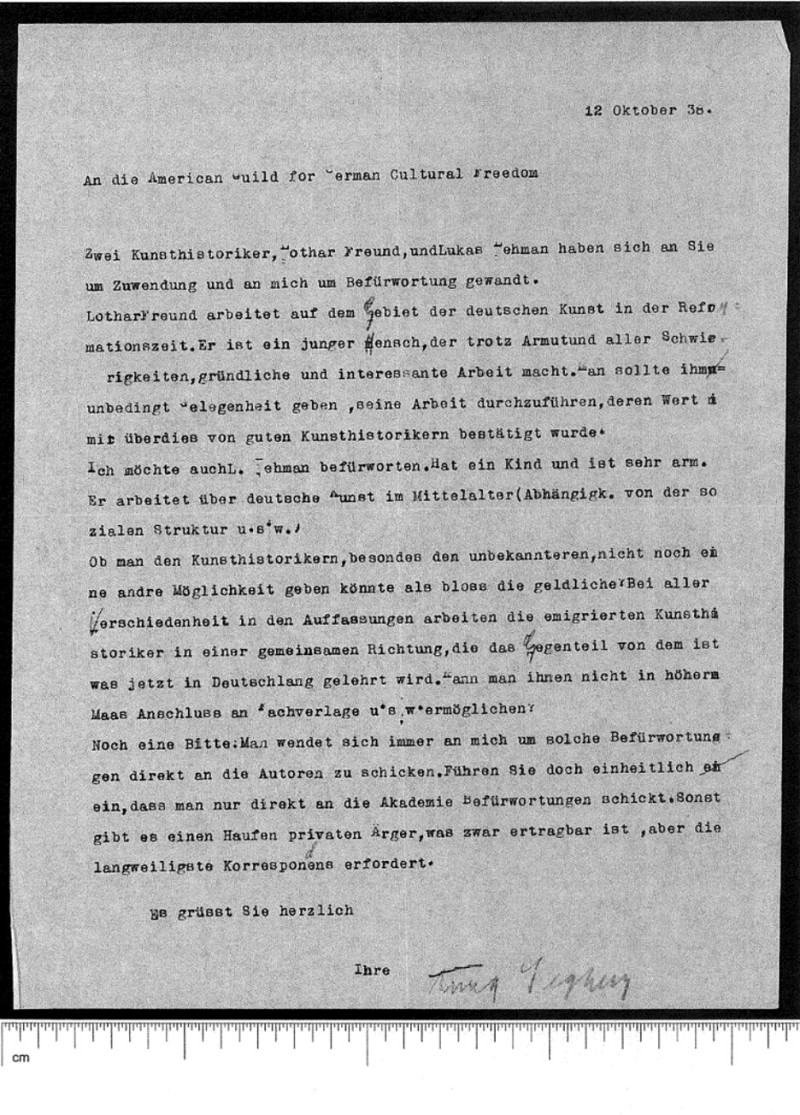

In this letter Anna Seghers vouches for Lothar Freud and Lukas Lehman to receive aid from the American Guild for German Cultural Freedom, so…

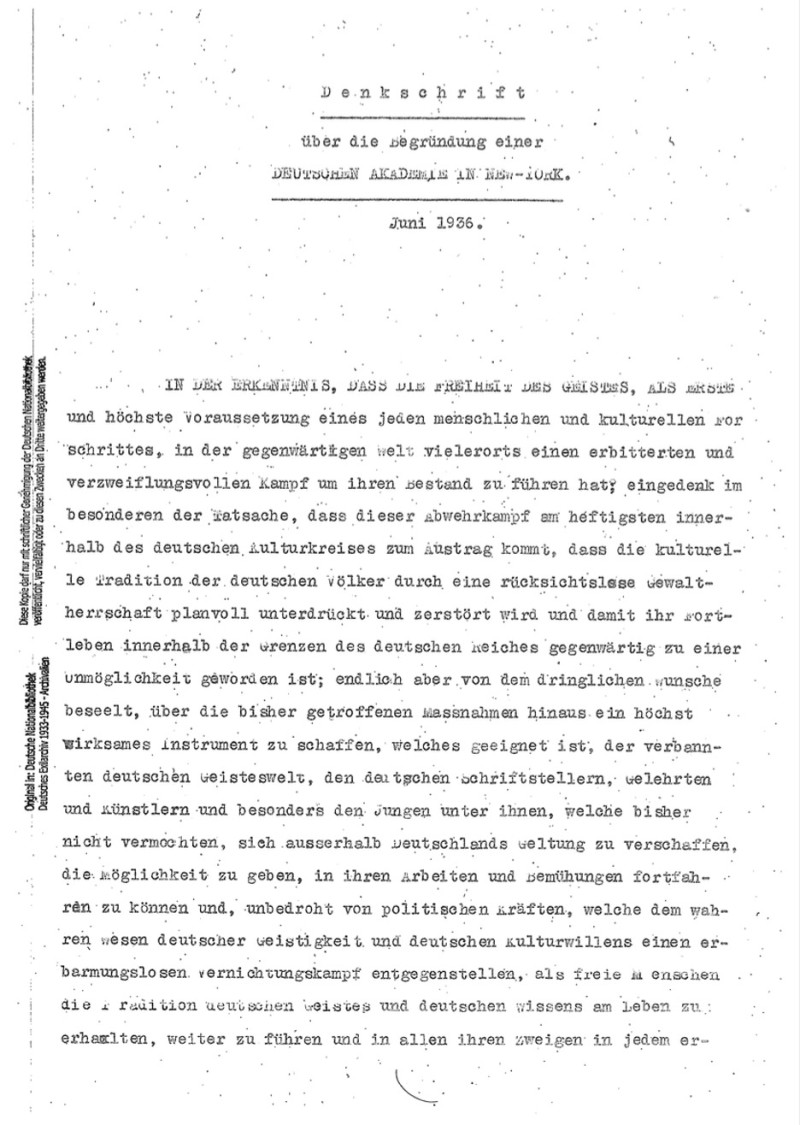

This memorandum clarifies the creation of the German Academy of Arts and Sciences together with the American Guild for German Cultural Freedom in New…

Hertha Nathorff, née Einstein (1895-1993) was a German pediatrician, psychotherapist and social worker. Until 1934 she worked as a senior physician at the Red…

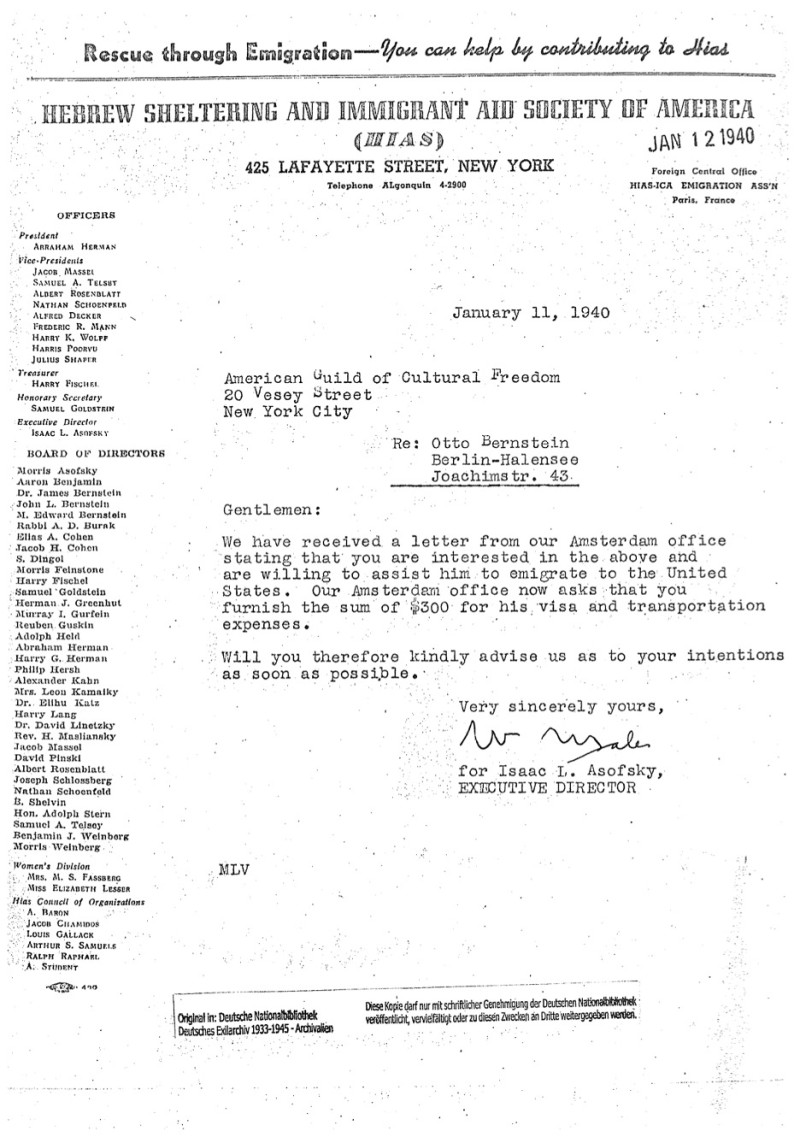

Otto Bernstein and his wife Jenny Schaffer-Bernstein both need financial support in order to flee Germany. In this letter the Hebrew Sheltering And Immigrant…

Hilde Marx (born November 1, 1911 in Bayreuth) was a German-American poet, writer and journalist. She is one of the authors whose writing career…

6

6

Fred Stein (1909-1967) began to make photography his profession after his escape from Nazi Germany to Paris in 1933. Besides street photography, portraiture became…

Harry Asher- originally Georg Auscher – born in Vienna in 1907. In 1920 the family moved to Czechoslovakia, where his parents came from. At…

The author of the novel “A Jewish Refugee in New York” Kadya Molodovsky is one of the most important Yiddish poets of the mid-20th…

In a diary entry in New York on June 20, 1941, the poet Mascha Kaléko (1907-1975) describes the many, mainly material, worries as a…

In her work “A Jewish Refugee in New York” Kadya Molodowsky presents the life of the twenty-year-old refugee from Lublin Rivke Zilberg in New…