Reflections on the unequal treatment of refugees and migrants, whether they are citizens, stateless persons or foreigners, permeate the entire We Refugees Archive in the historical and current self-testimonies.

The existing law, which presupposes national citizenship, allows discrimination against non-citizens: a socially accepted grievance that reveals the substantial ambivalence between the claim to universal human rights and the factual rights of citizens. Hannah Arendt already formulated this discrepancy in 1951 in her analysis of totalitarian rule:

“Statelessness in a mass dimension has set before the world, the inescapable and highly puzzling question of whether or not there is such a thing as inalienable human rights, which are independent of any particular political status and only arise out of the mere fact of being human.”

The protection against discrimination thus relates to citizens of nation states only and largely excludes both citizens of foreign states on the territory of another state and stateless persons, albeit nation-state citizens are also affected by discrimination on the basis of other categories.

Given that the current denial of immigration and residence rights for so-called “economic migrants” is widely accepted, the prohibition of discrimination in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948 (Art. 2) remains highly relevant for overcoming it:

Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.

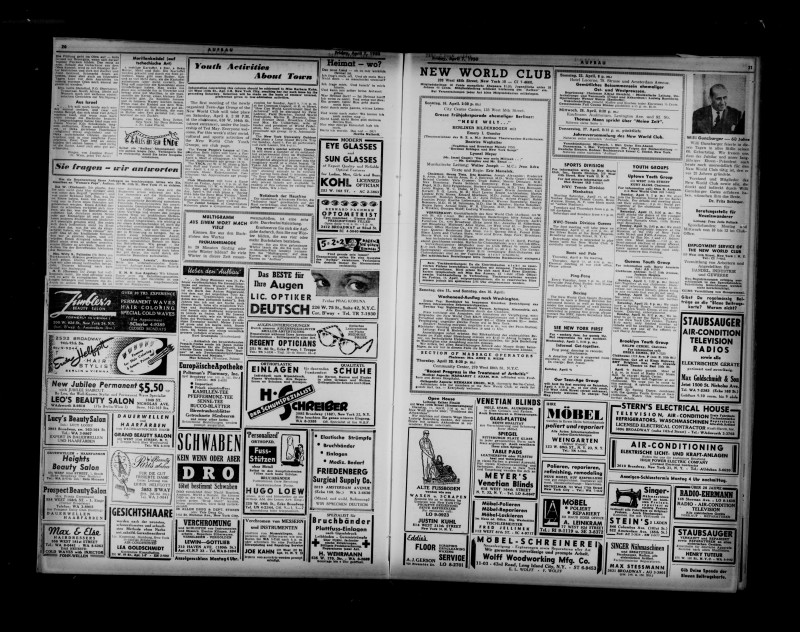

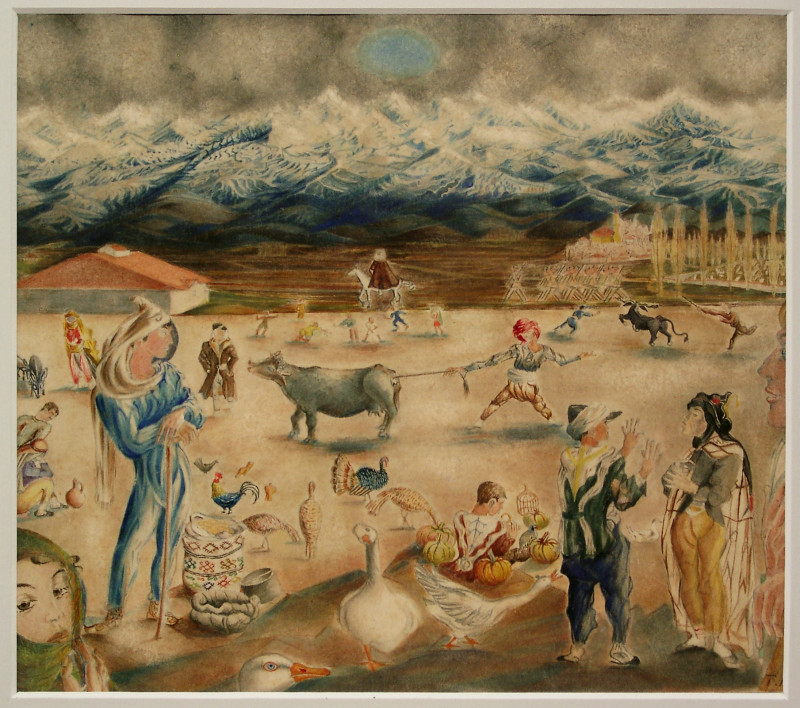

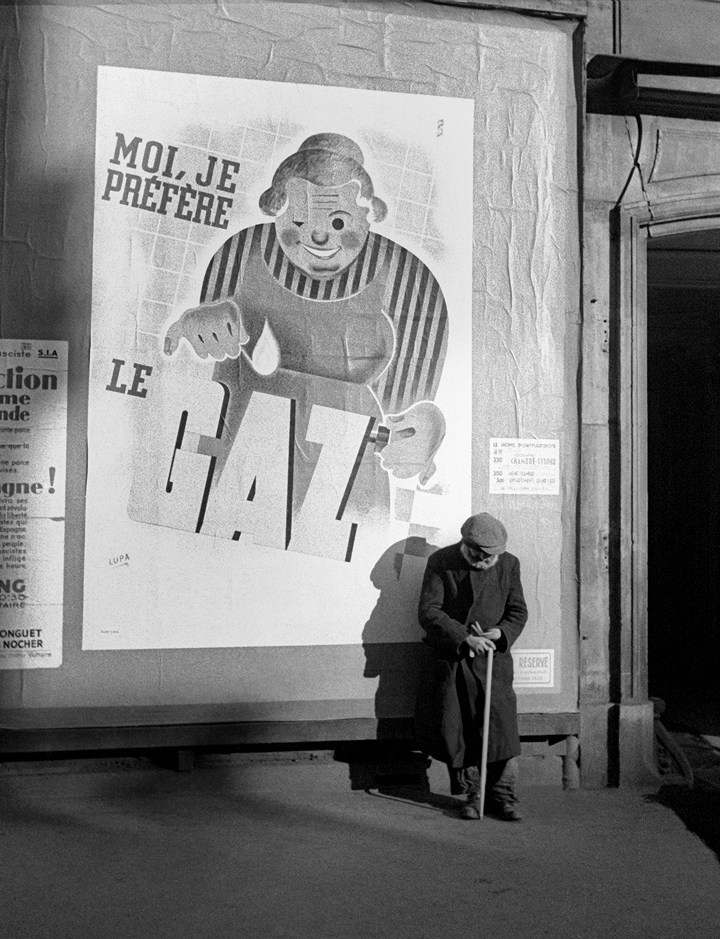

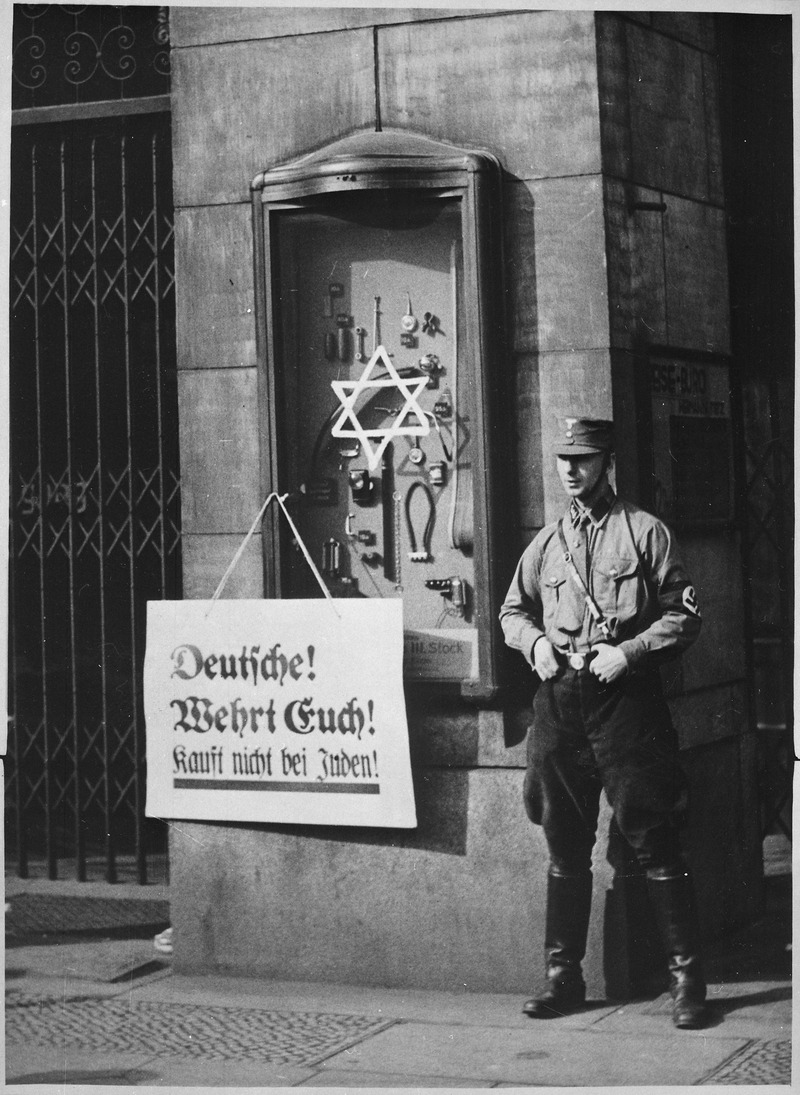

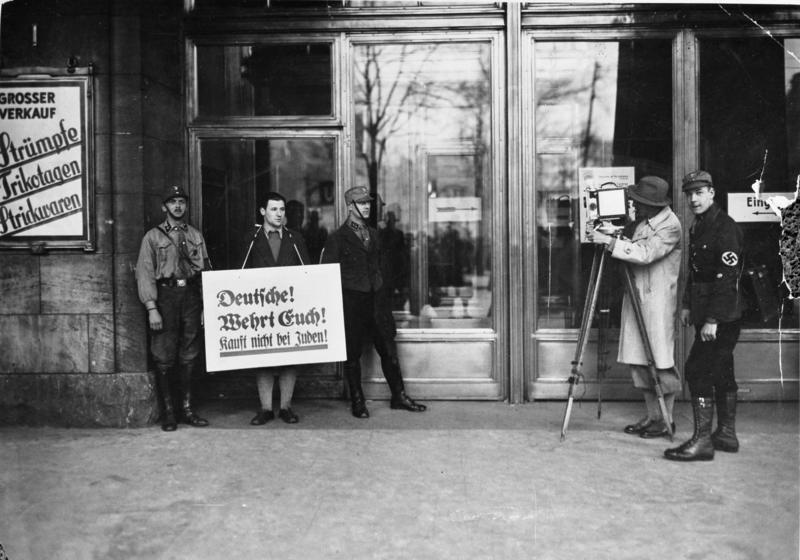

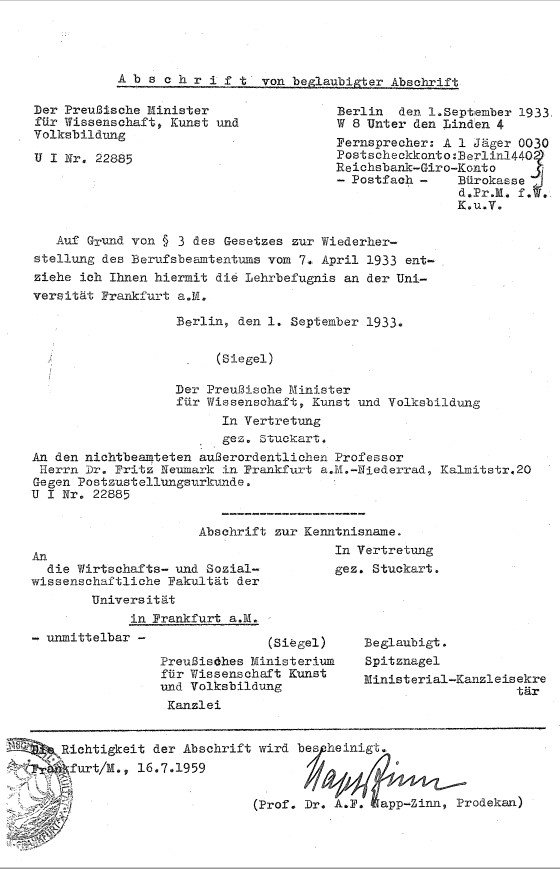

Within the borders of a state, exclusion or “doing borders” takes place and manifests itself in unequal access to rights, resources and space at national and local level, i.e. at the level of the municipalities: in schools, in employment agencies, on the labour and housing markets and in public debates. The mechanisms of exclusion which are effective here prevent the integration which society demands of migrants. This lack of access to social resources has been experienced by refugees in the past and continues to be a refugee experience today: In 1930s Paris, the emigrees tried desperately to make a living despite the wide-ranging prohibition to work; in 2010s Berlin, it is mainly refugees with an insecure residence status, such as the Duldung (tolerated stay permit), who have hardly any chance of building a life in the new place and participating in society through work and education because they are not issued a work permit. Even if the construct of “illegal migration” remains prevalent throughout history, the legal categories that justify this exclusion are exchangeable and often arbitrary. This was expressed in particular absurdity in the Second World War by the category of the “enemy alien”, which justified the internment of people from hostile states, even if they had been persecuted by precisely these states (especially Germany) and had had their citizenship revoked, and had been disadvantaged because of their emigration before the war began.

In addition, there are many barriers that prevent the enforcement of the legally provided protection against discrimination by state and non-state actors: Refugees without a secure residence status, for example, are often reluctant to report experienced discrimination for fear that this could result in disadvantages for them and their recognition process.

There are also measures that serve to seal off and exclude refugees and secure the borders “inside”, e.g. in the form of the current residence obligation, collective accommodation, massive police operations against protests by refugees or racial profiling of police officers.

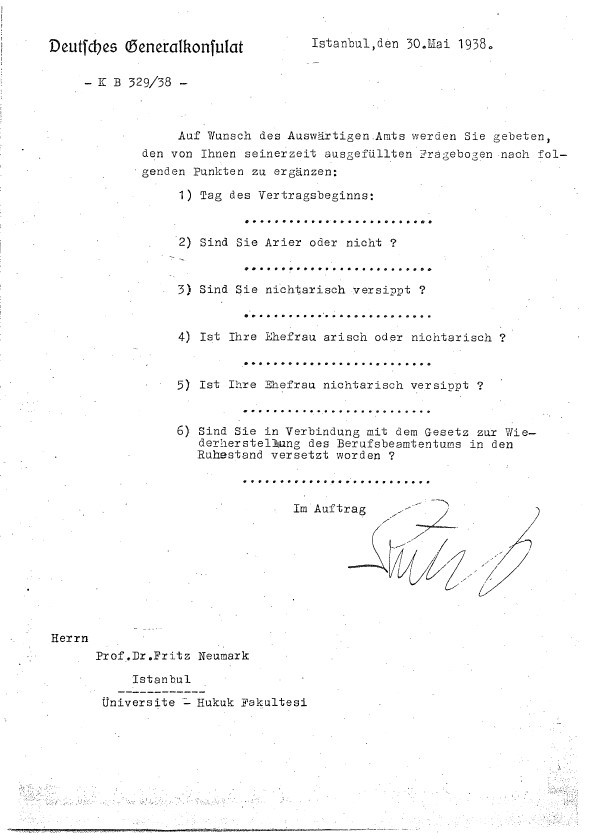

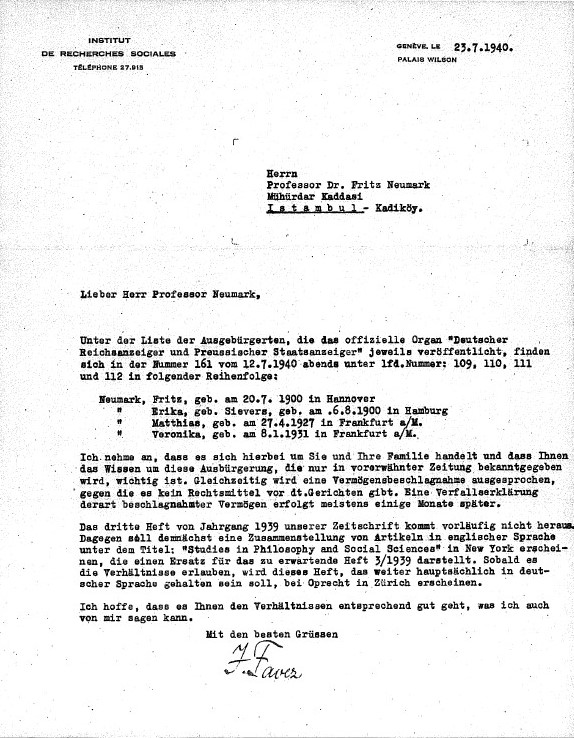

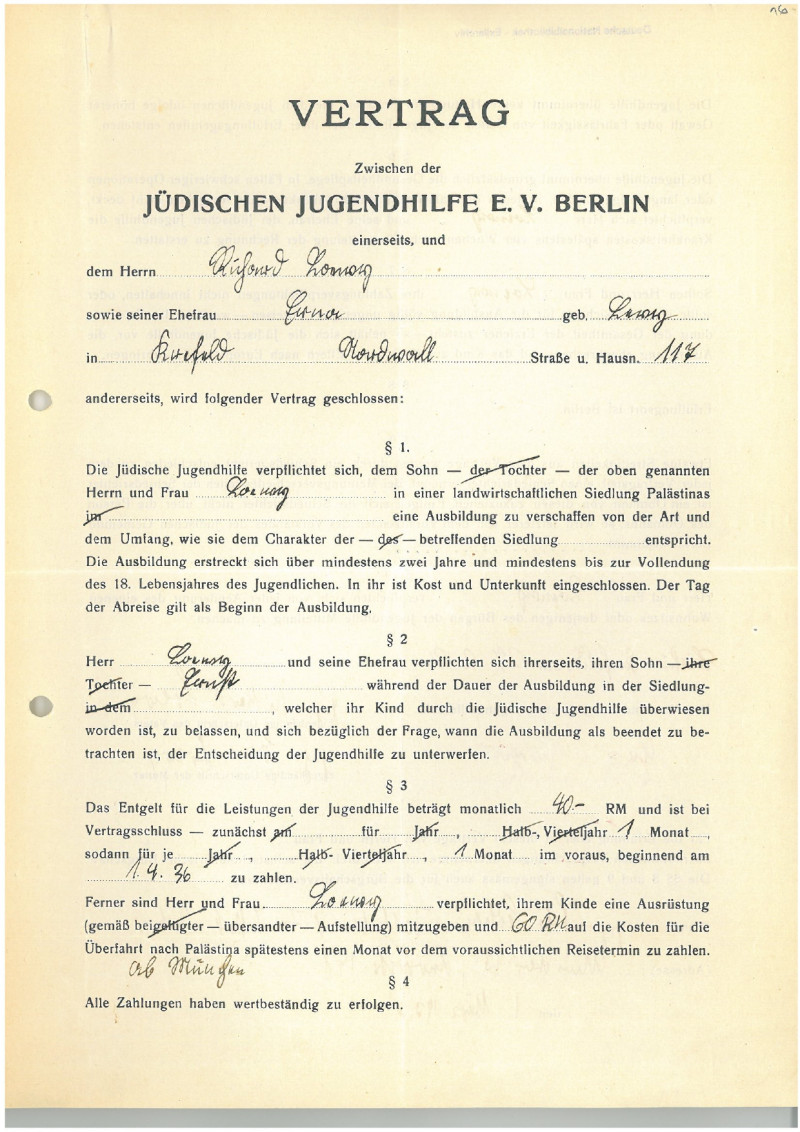

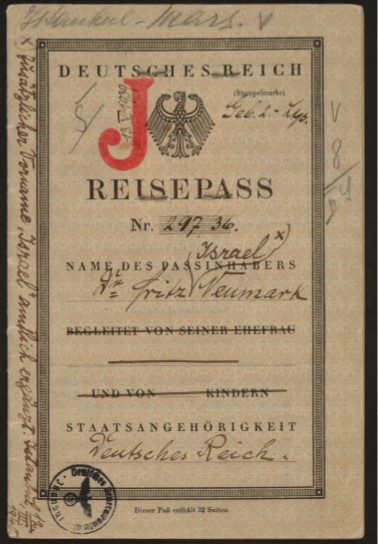

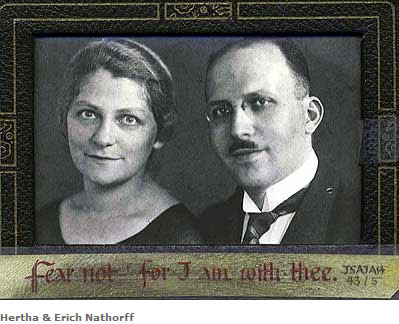

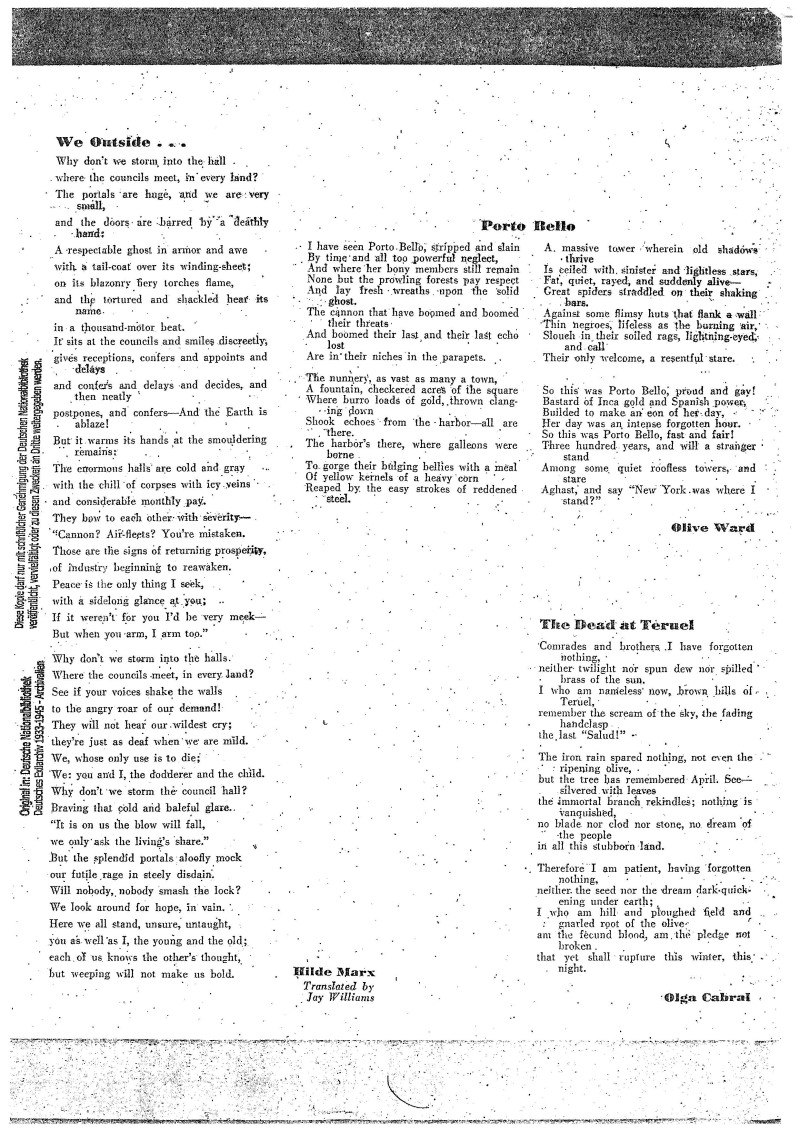

In most cases, however, the exclusion of refugees already takes place in front of the borders of nation states or group of states. While the own borders are more and more secured, nowadays the “migration problem” is often externalised: The European Union, for example, invests far before its own borders in deterring migrants and makes deals with third countries to take care of their supply and prevent them from continuing their way towards the “own” borders. Large camps for refugees are also an expression of this local and legal exclusion at and in front of the borders, for example of Europe: the provisional state of a camp becomes a permanent state of undersupply and disenfranchisement and ensures the separation from the “normal” life of society. This policy of isolation also has a long history: reports of no-man’s-lands in front of closed borders of states not willing to accept refugees and the desperate struggle for visas that would enable people to flee from the advancing German National Socialists in Europe fill the historical self-testimonies. Negotiations on an international reception of the refugees, as at the 1938 Évian Conference, failed in a similar way to today’s futile attempts to push through common and fairly distributed reception strategies against national egoism.

In case refugees are able to reach a safe place and are given a residence permit, they are subject to societal discrimination. All experiences of discrimination shared by people in We Refugees Archive have in common that people are targeted because of their existence as refugees, their appearance, their name, their (ascribed) origin or their apparent identity.

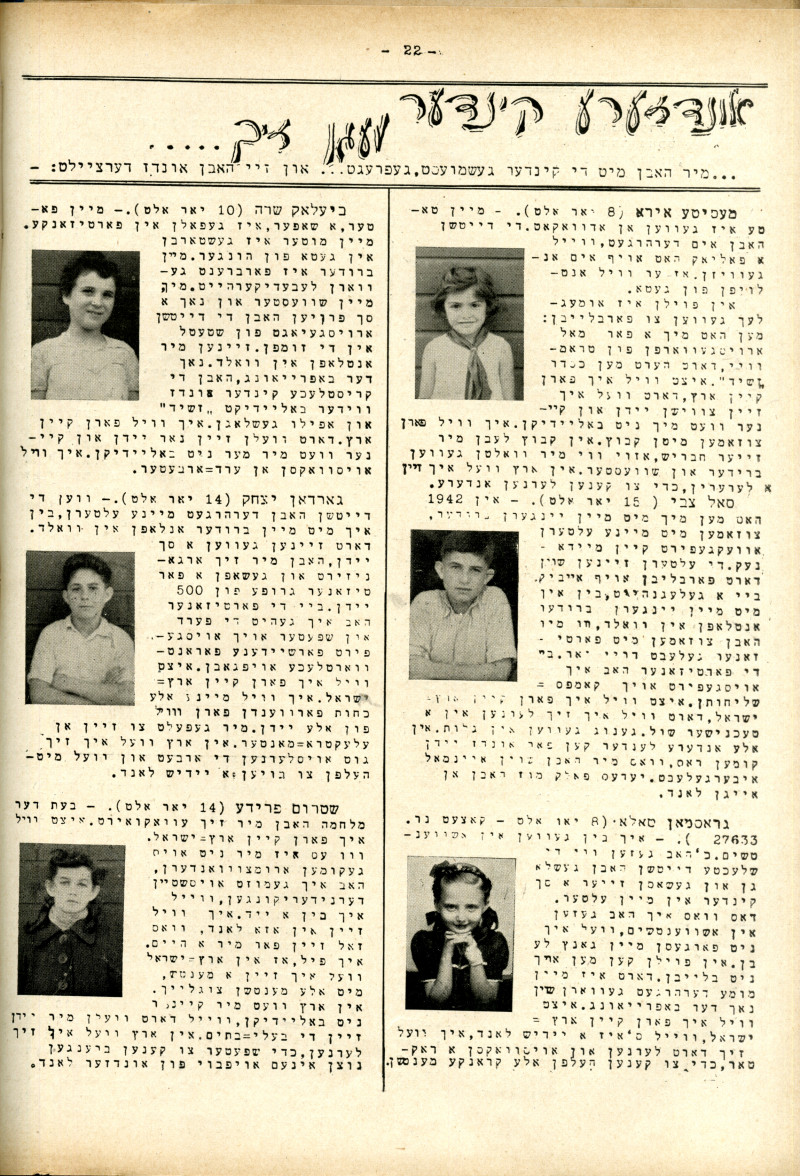

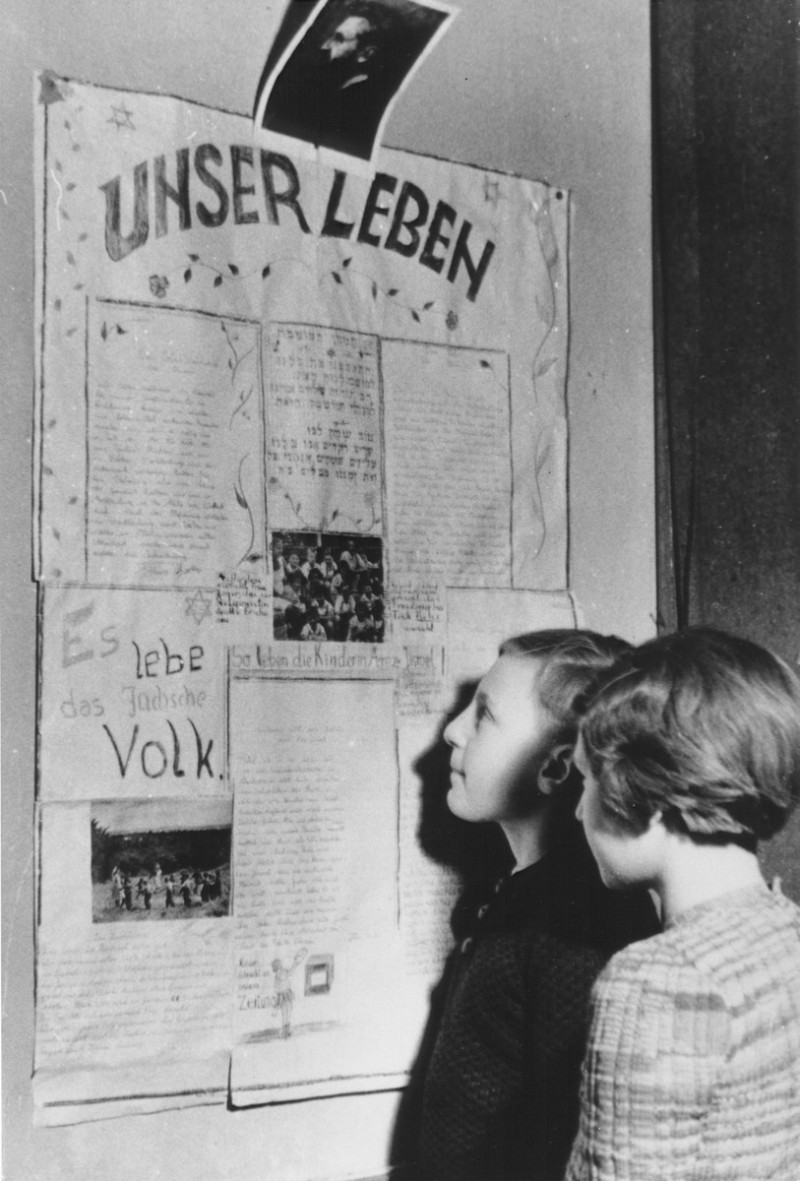

The structural and social exclusion mechanisms existing above and a stereotyping discourse then and now about “the refugees” mean that these people not only feel exposed to practical discrimination, but also suffer from no longer being recognised in the complexity of their human identity and diversity.

The self-testimonies in the past and present point to unequal treatment, lack of representation and blocked access to social and vital resources. Often the mistrust whether one is “really a refugee” plays a central role. Another burdening aspect is intersectional discrimination, e.g. for Black women who fled or queer refugees who, having escaped persecution in their home country, continue to be discriminated against in Germany and are especially vulnerable due to mutliple discrimation categories ascribed to them. The analysis of the interviews shows that multi-dimensional (intersectional) discrimination can influence many individual life situations and increase exclusion from central social resources.