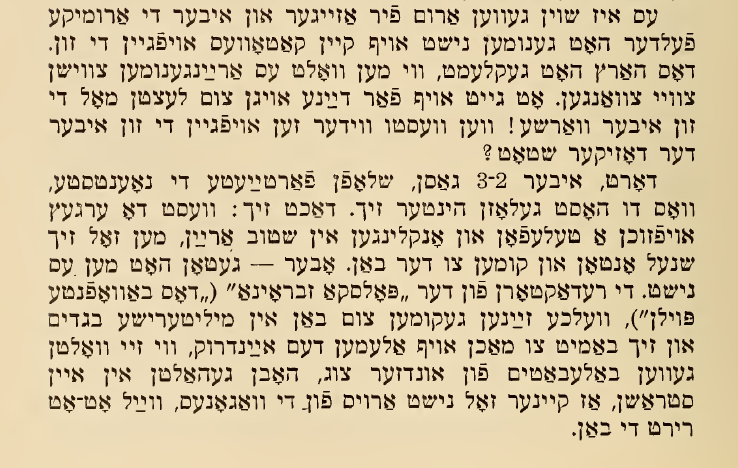

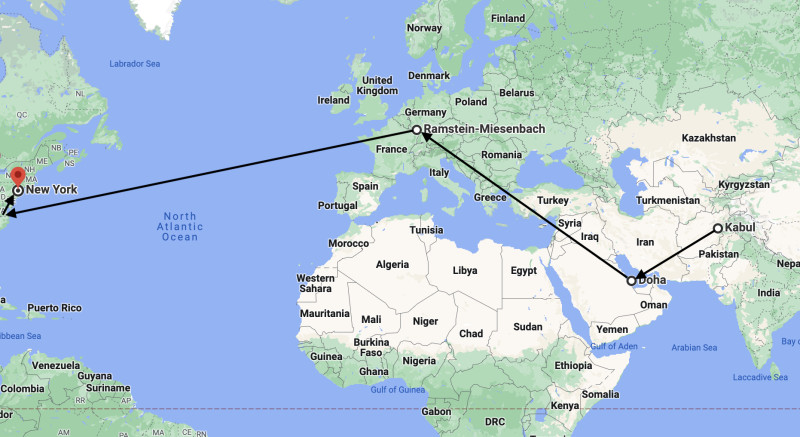

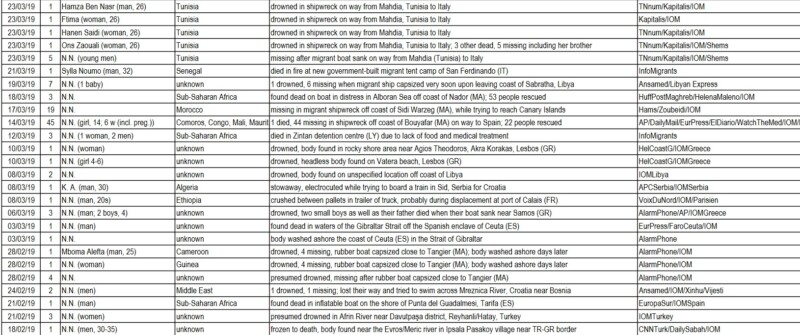

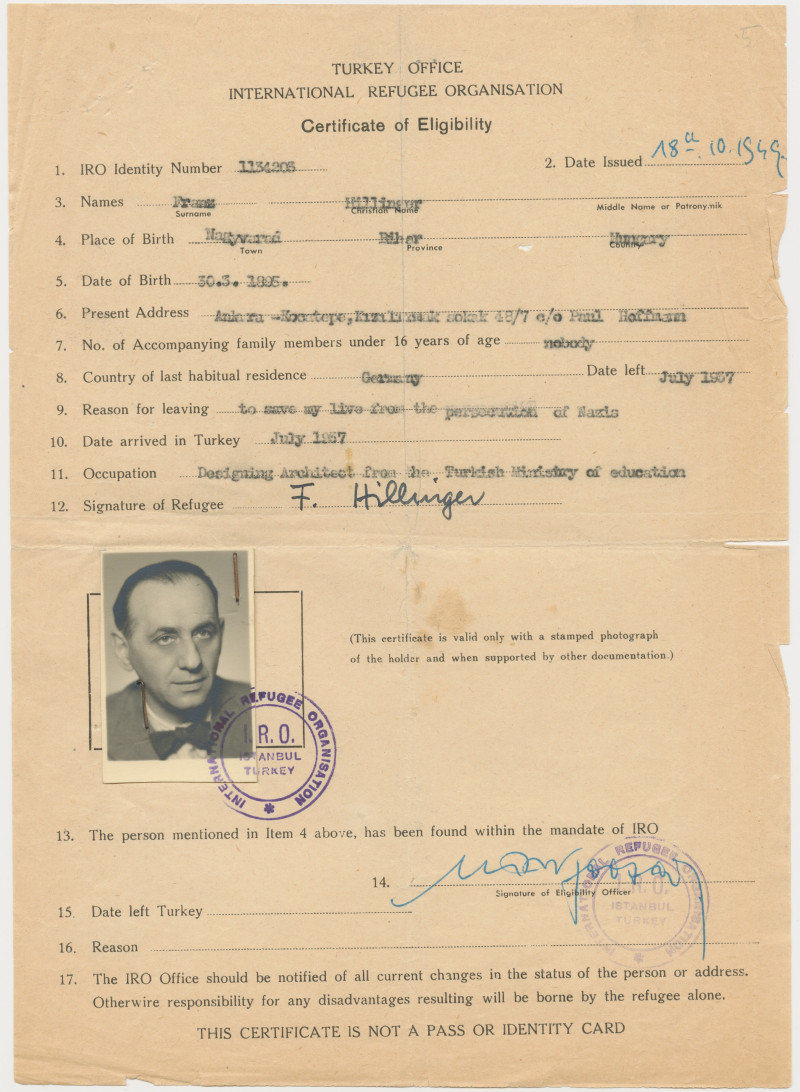

The decision to flee is or was made at a specific point in time due to a trigger or because of concrete personal reasons, even though, today as in the year 1939, extenuating circumstances left, or leave, little room for decision-making for people who are fleeing. The danger of staying at a place always has to be weighed against the danger of forced migration. For flight cannot be planned, it can be life-threatening, and brings with it traumatic experiences, leading one along unexpected routes and stopovers which may sometimes last years. This insecurity results from the lack of legal and protected routes for refugees and from the loss of rights and state protection, which Hannah Arendt in her analysis of statelessness has already described. It is due to the lack of official flight routes and support networks that stories of flight are important both of the (unofficial) aid and rescue networks for refugees and of those who wish to profit from people fleeing emergency situations.

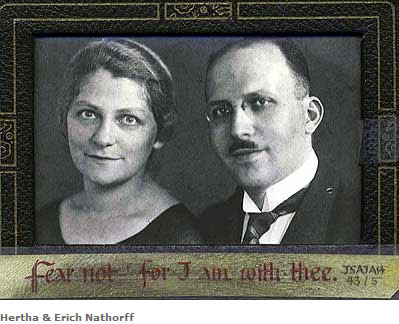

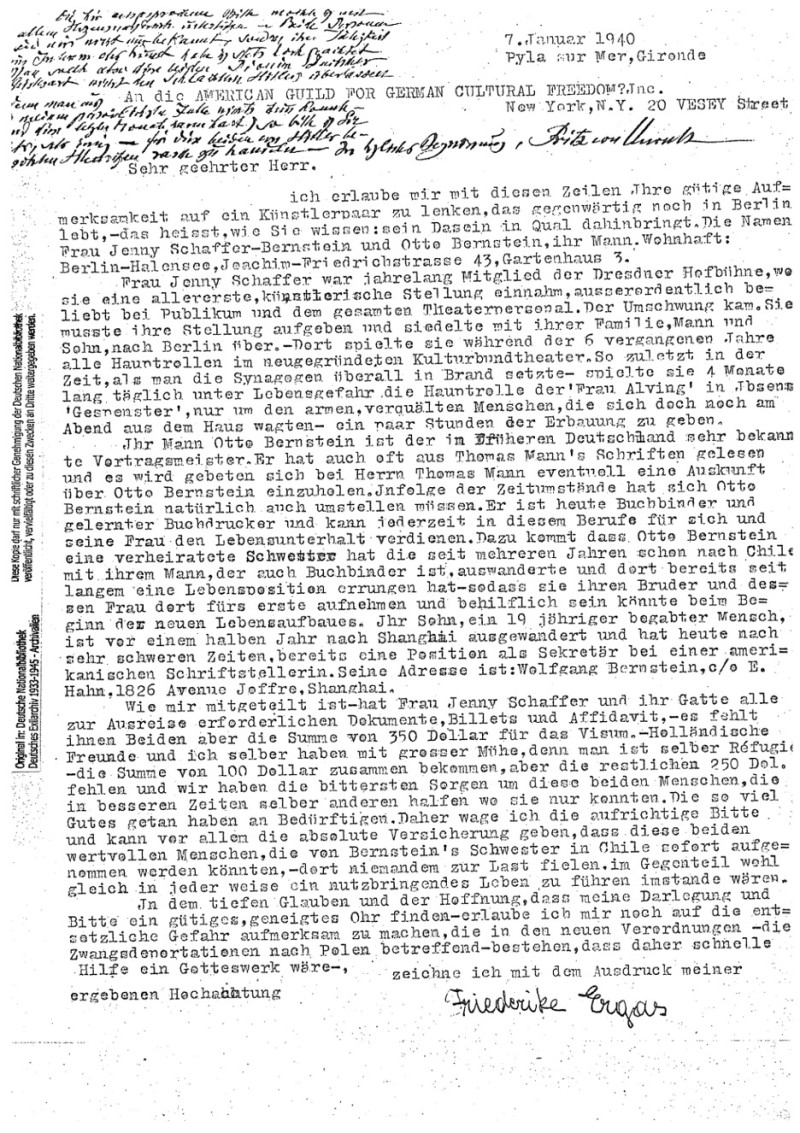

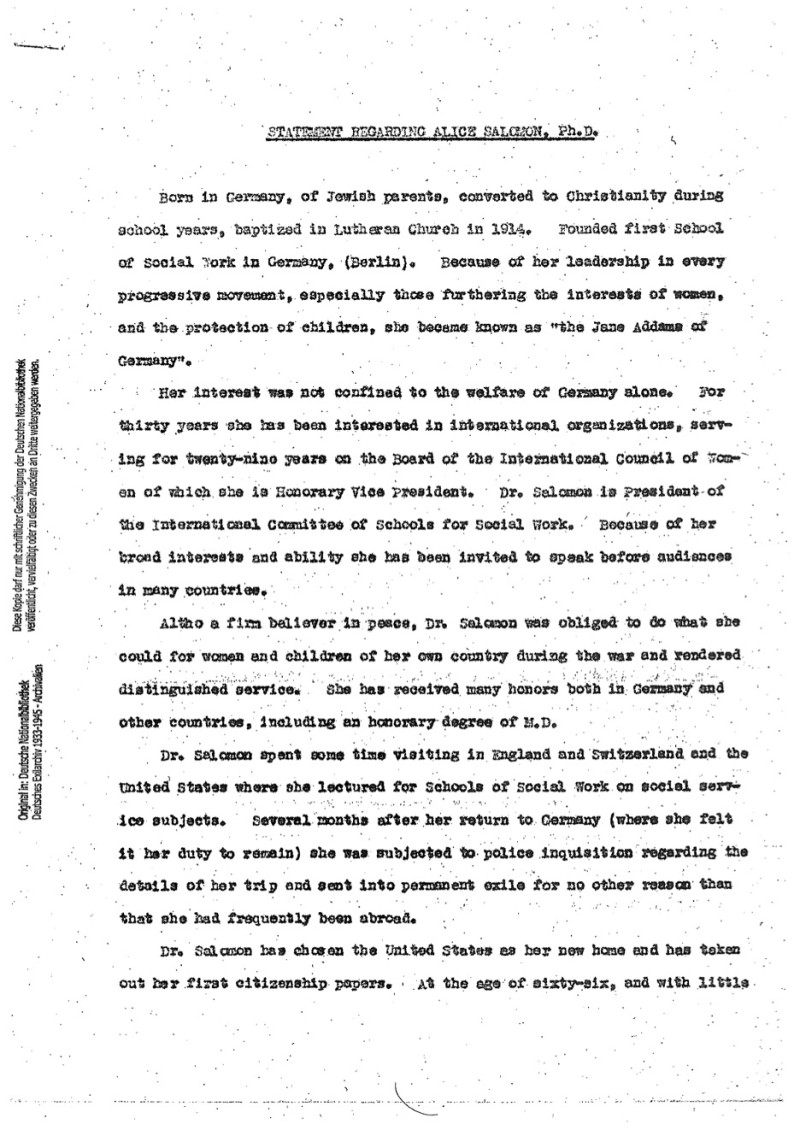

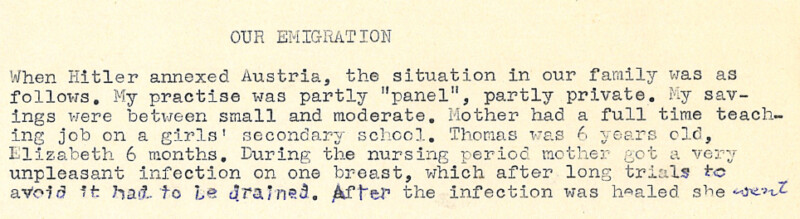

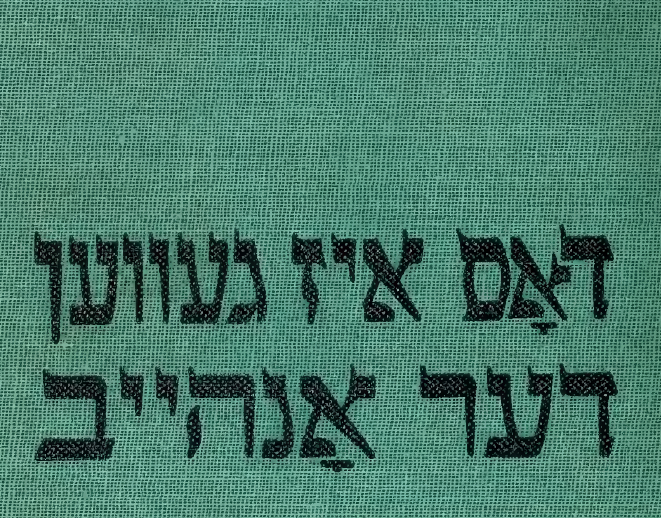

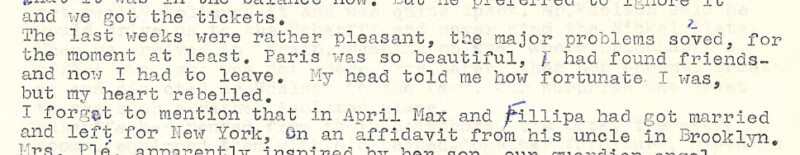

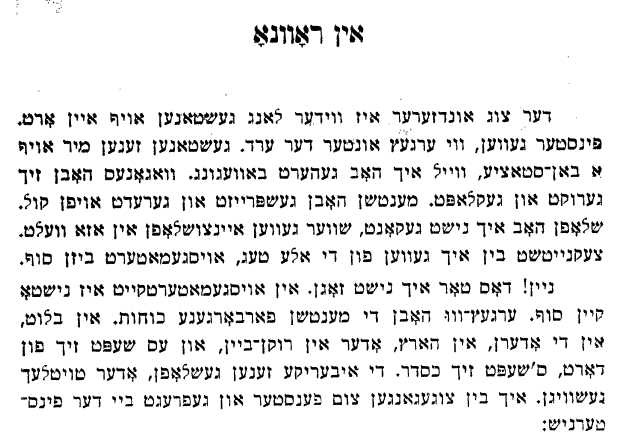

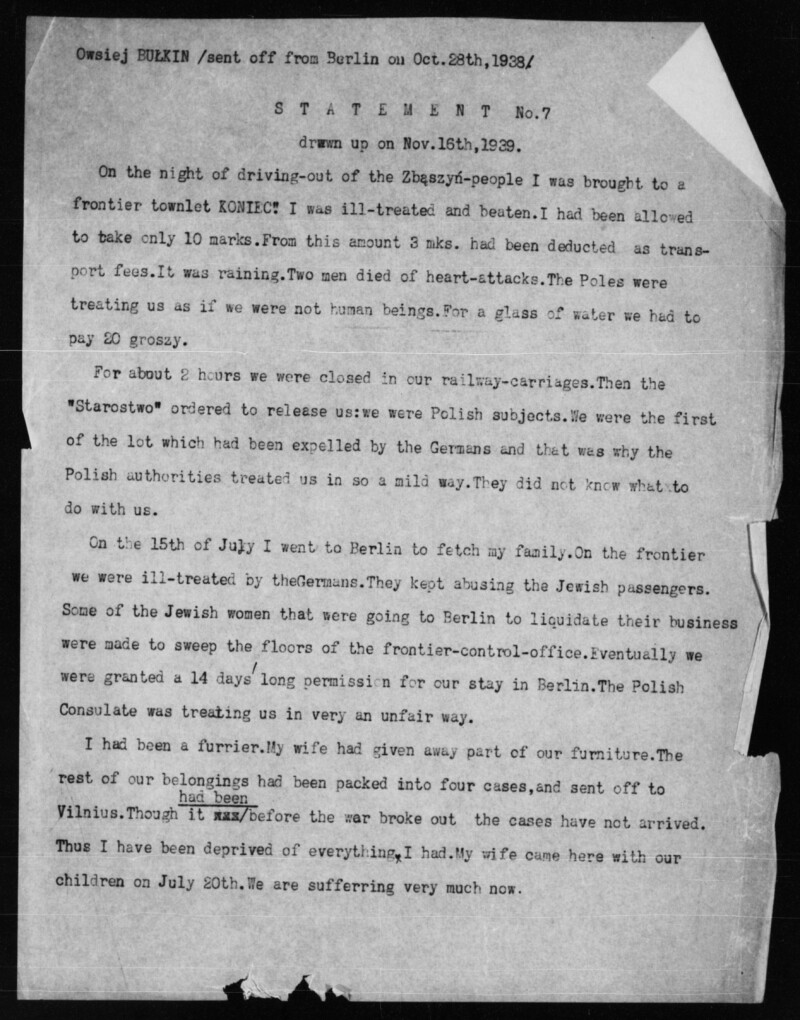

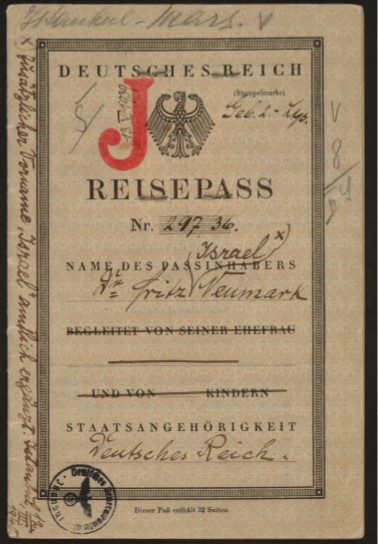

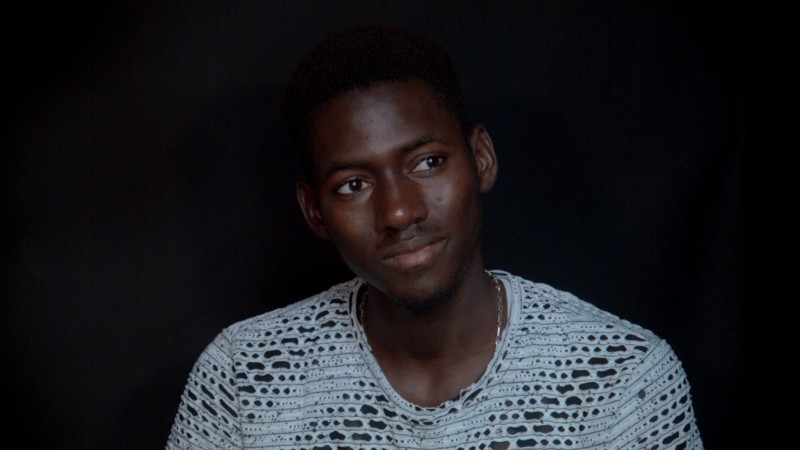

We Refugees Archive presents examples of contemporary experiences of refugees who decided to escape situations of civil war as well as the lack of prospects or other existential threats. Some testimonies show that people do not conceptualize their migration as flight. Whether, in the contemporary context, this stems from a desire to categorize their decision as voluntary despite certain coercive circumstances or as an attempt to circumvent negative, societal ascriptions can only be clarified on a personal level. Increasingly, one observes mixed forms of forced and voluntary migration, which make it more difficult to distinguish the motives and pathways of refugees and migrants. Conversely, the Jewish refugees spoke explicitly about their flight from the German occupiers. It is exactly this zooming in on individual experiences, however, that allows for many parallels to arise in terms of one’s self-reflection on flight: the reasons, the decisions made, the parting and the dangers of the escape routes that shape and occupy those people who flee even after their arrival at a secure place. The baggage of refuge will stay with people even when they have arrived.

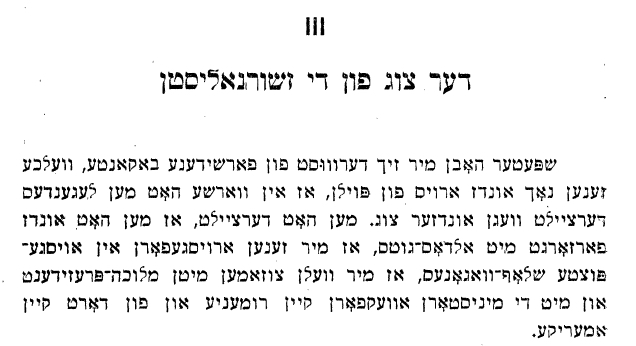

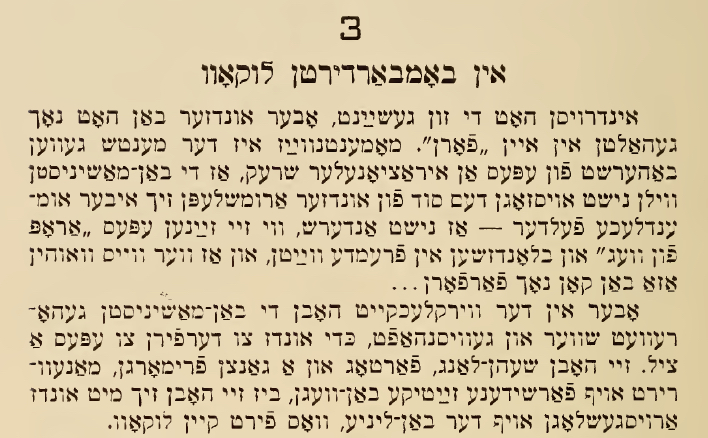

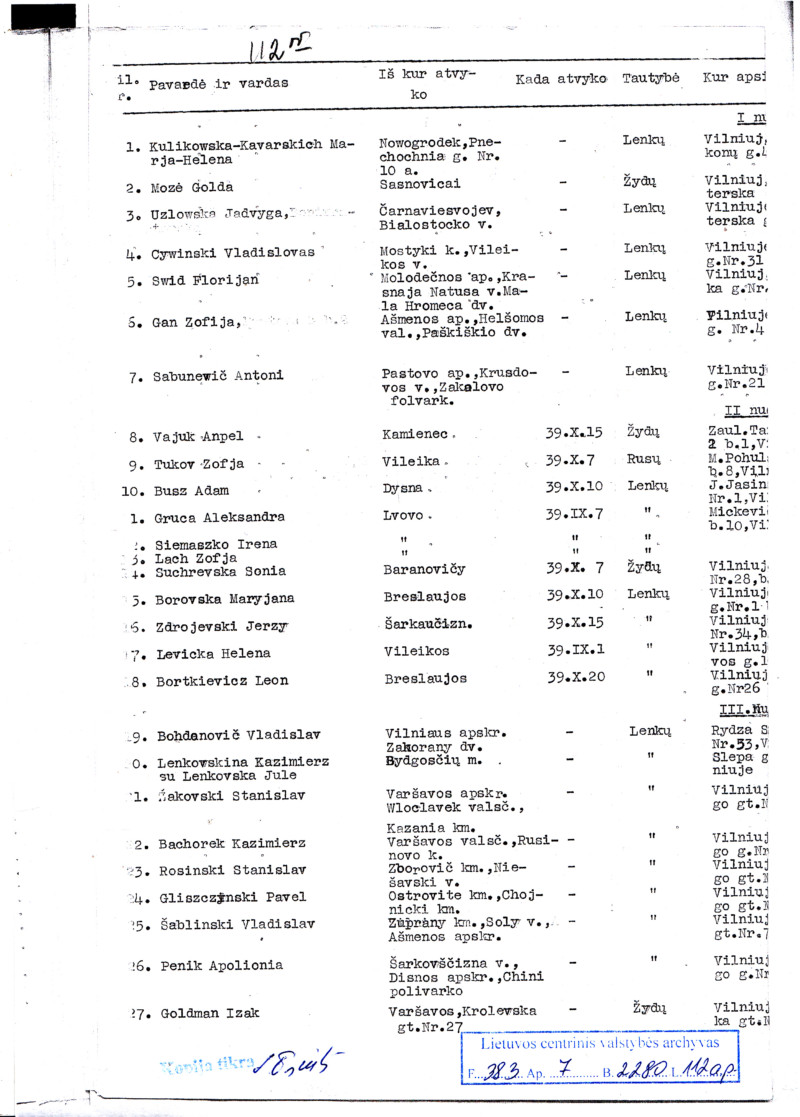

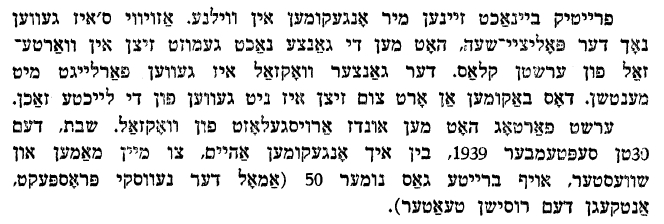

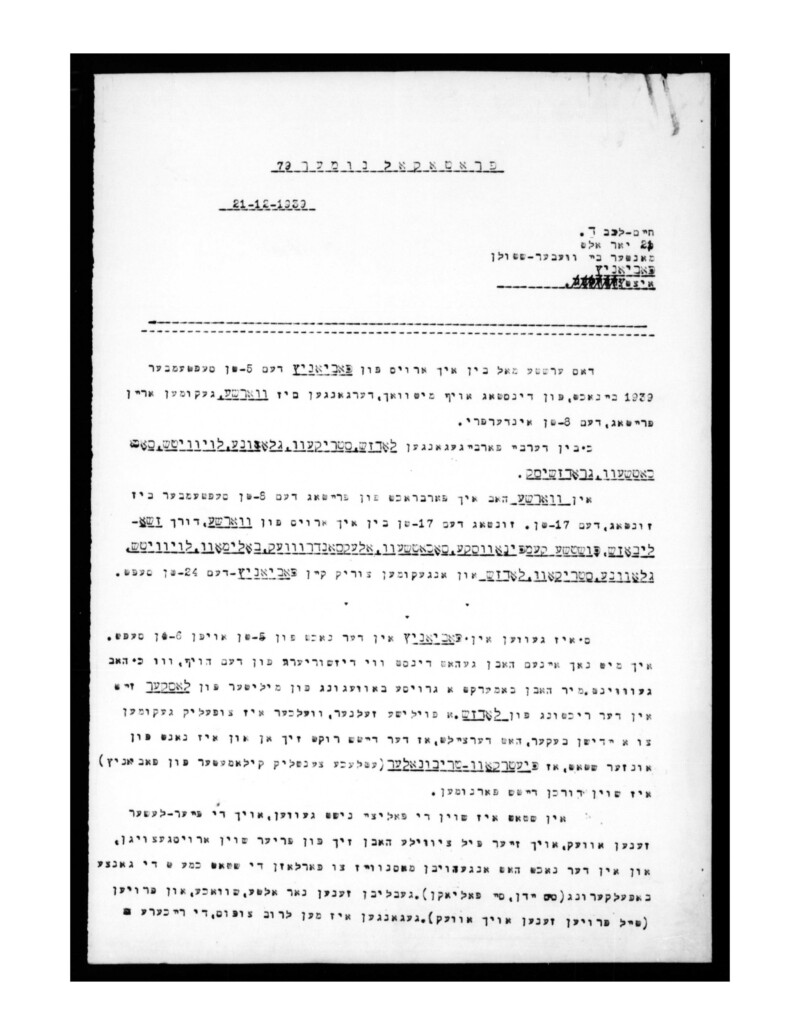

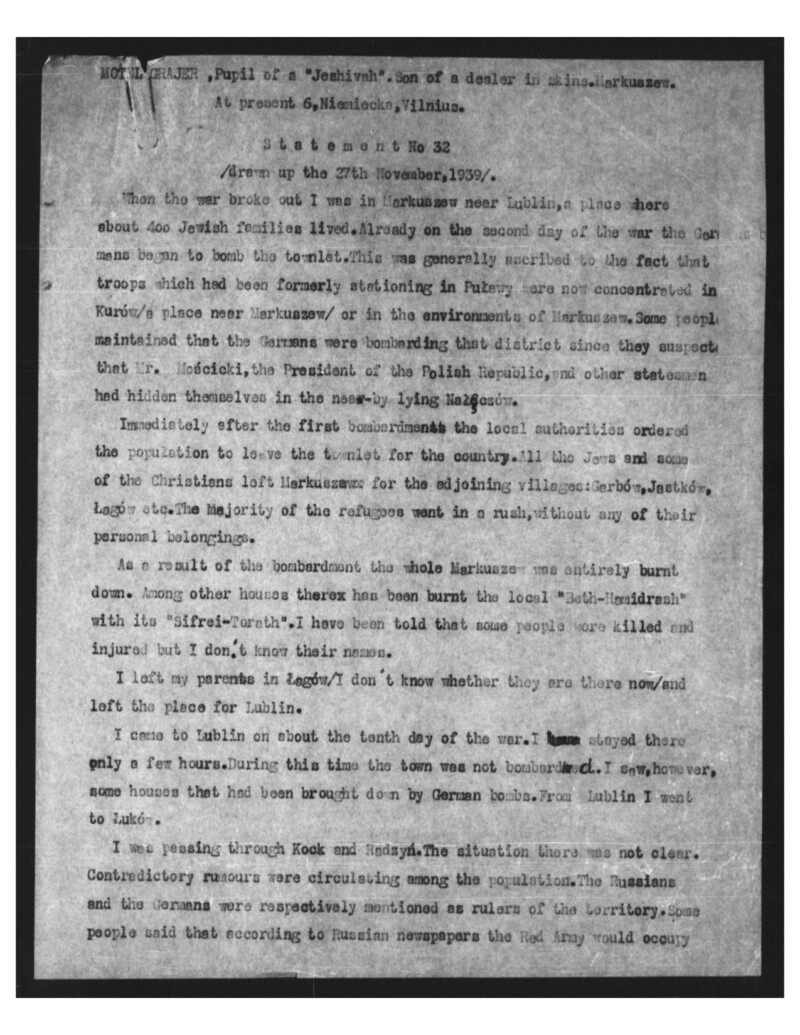

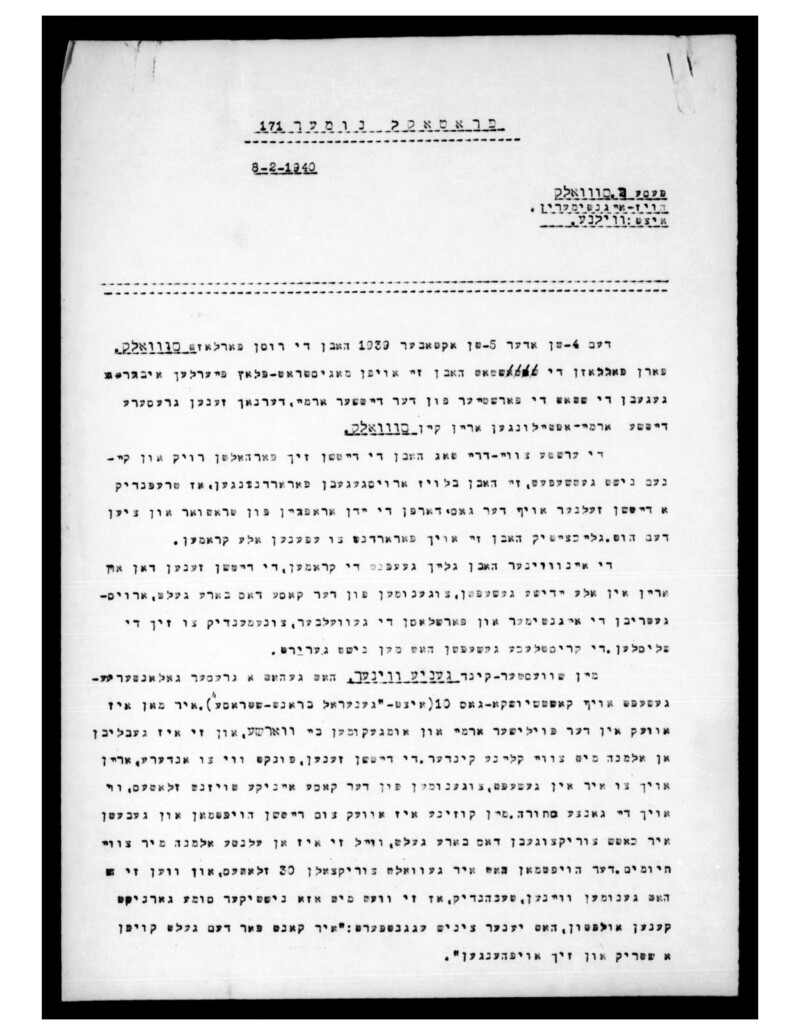

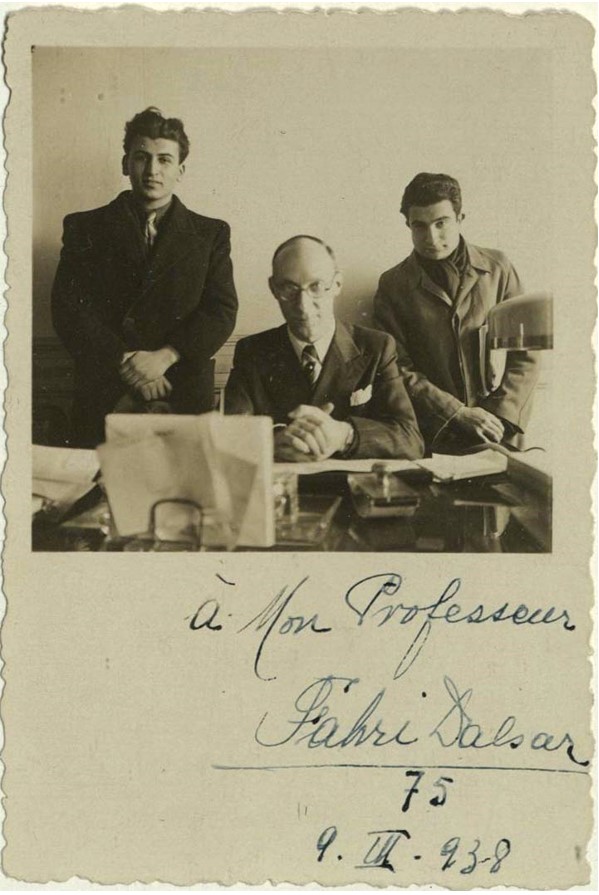

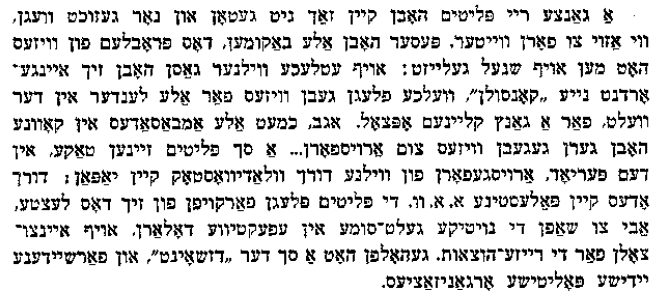

The example of the panic-stricken and sudden flight of Jews from the Wehrmacht invading Poland to the still neutral and safe Vilnius in the autumn of 1939 is different from the flight from constantly insecure and hopeless conditions described by young refugees in Palermo or elsewhere today.

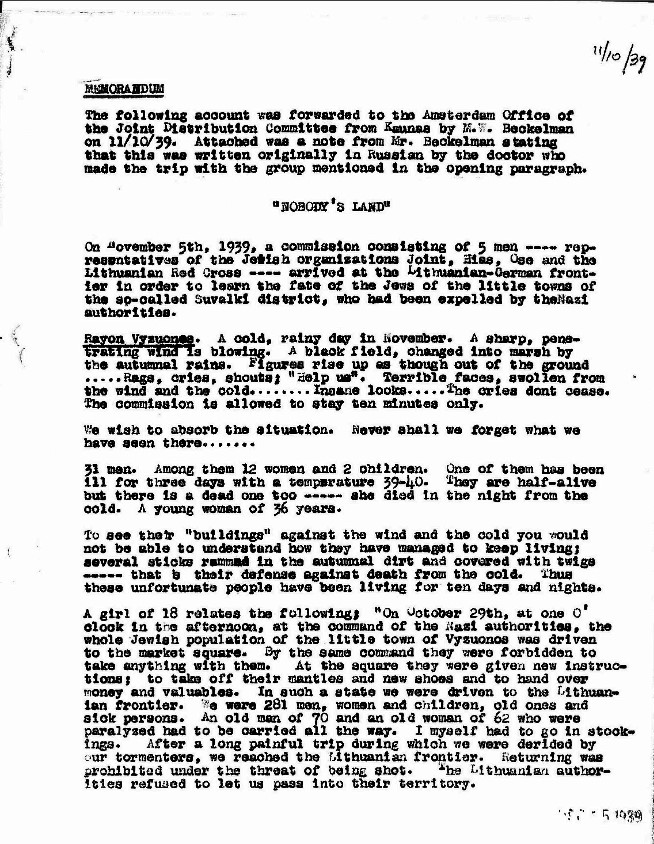

Certain refugee areas, no-man’s-lands and dead ends become symbols of the personal and political confrontation with flight: These include the Mediterranean and so-called “no-man’s-lands”, which were created during the Second World War as lawless dead ends in border areas. The area near Suwałki on the former border between occupied Poland and still unoccupied Lithuania is just one example among many. No-man’s-lands are still emerging in Europe and worldwide today: lawless non-places where fugitives have to endure terrible conditions.

Whether the people who found temporary refuge in Vilnius were able to save their lives through further stages of escape is unknown. After the German occupation of Lithuania, the Jewish population and the Jewish refugees in Lithuania were almost all murdered.

At this point it is impossible to compare the historical flight to Vilnius with the experiences of refugees who have arrived in today’s Palermo. On the other hand, their experiences are survivor stories and therefore do not speak for all those who died on the way to Sicily.