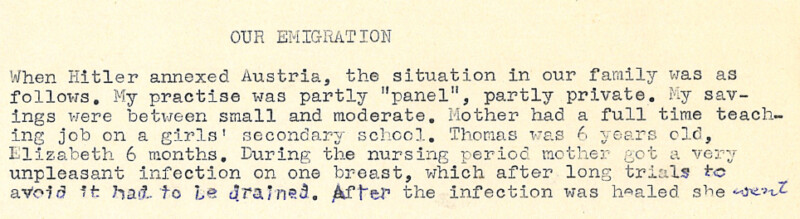

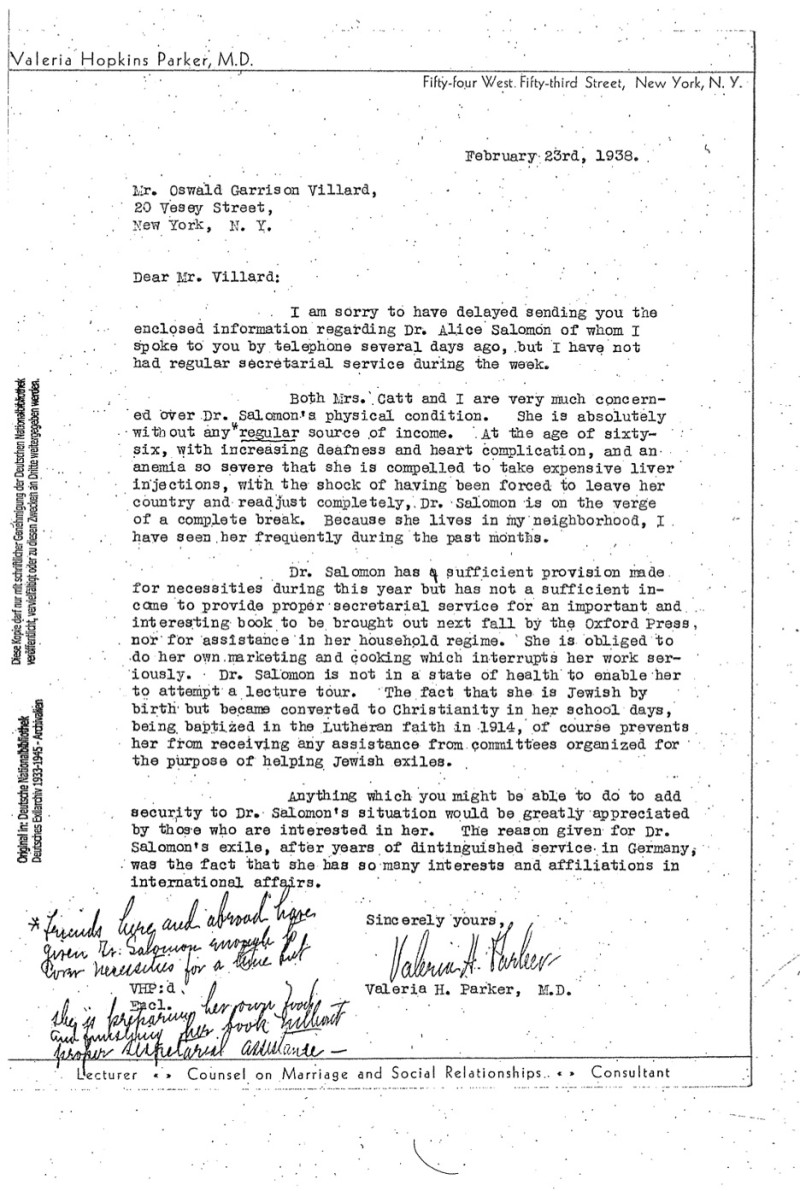

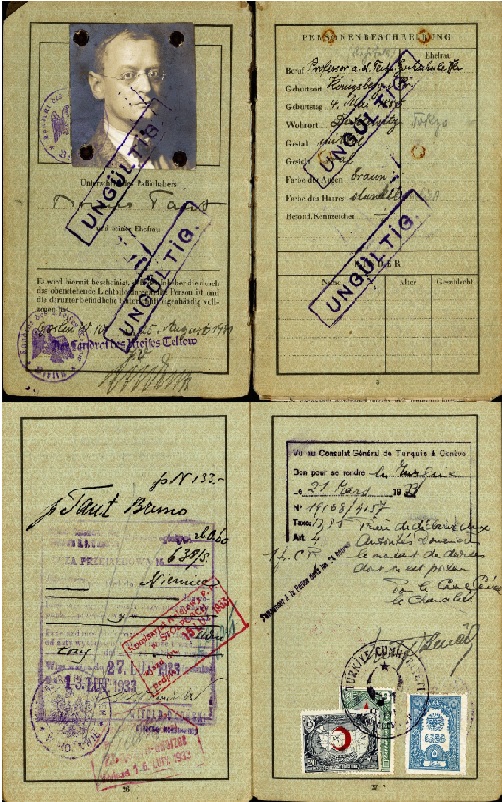

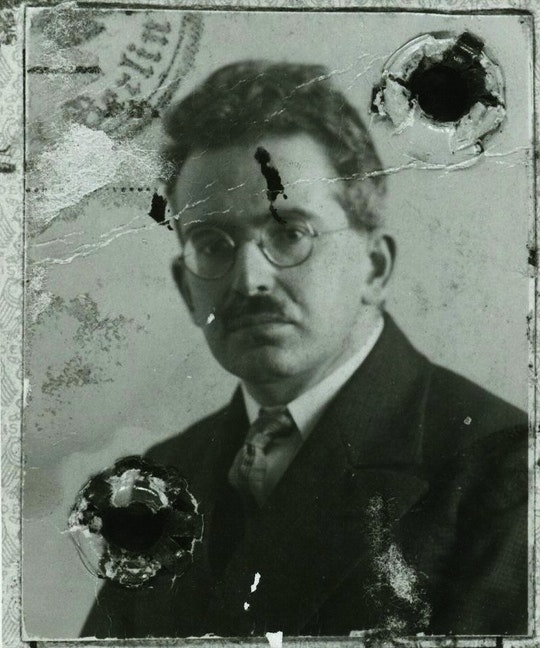

“Now ‘refugees’ are those of us who have been so unfortunate as to arrive in a new country without means and have to be helped by refugee committees.”

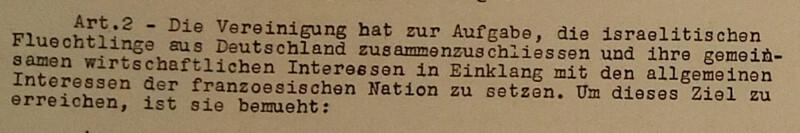

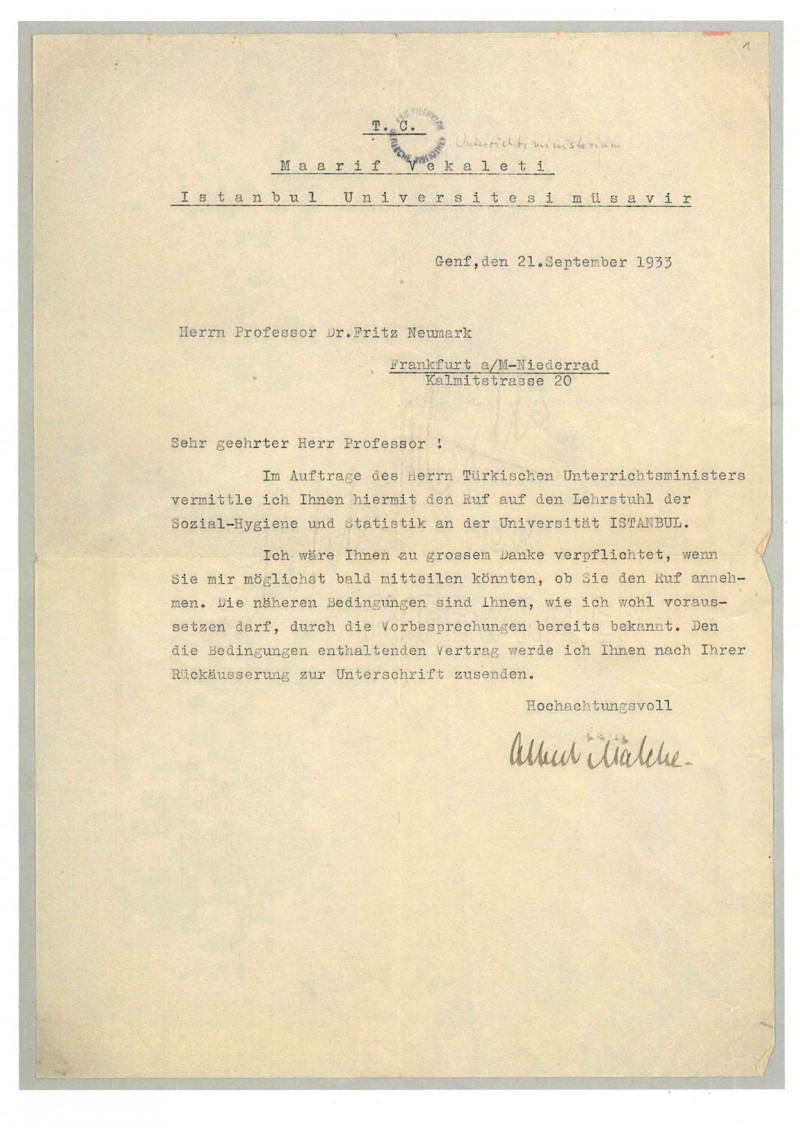

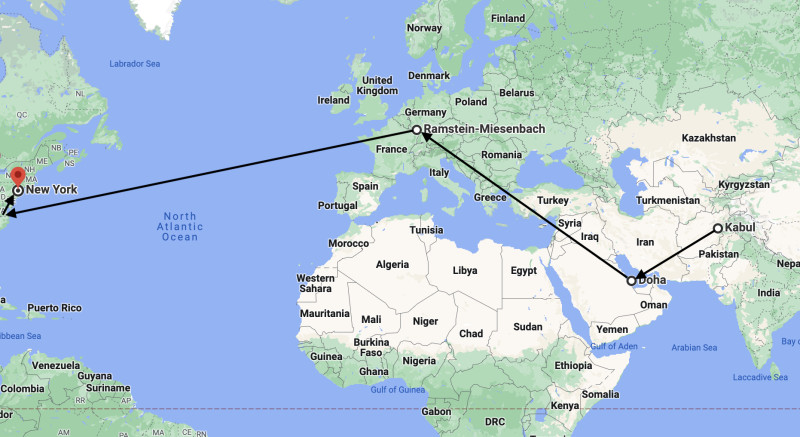

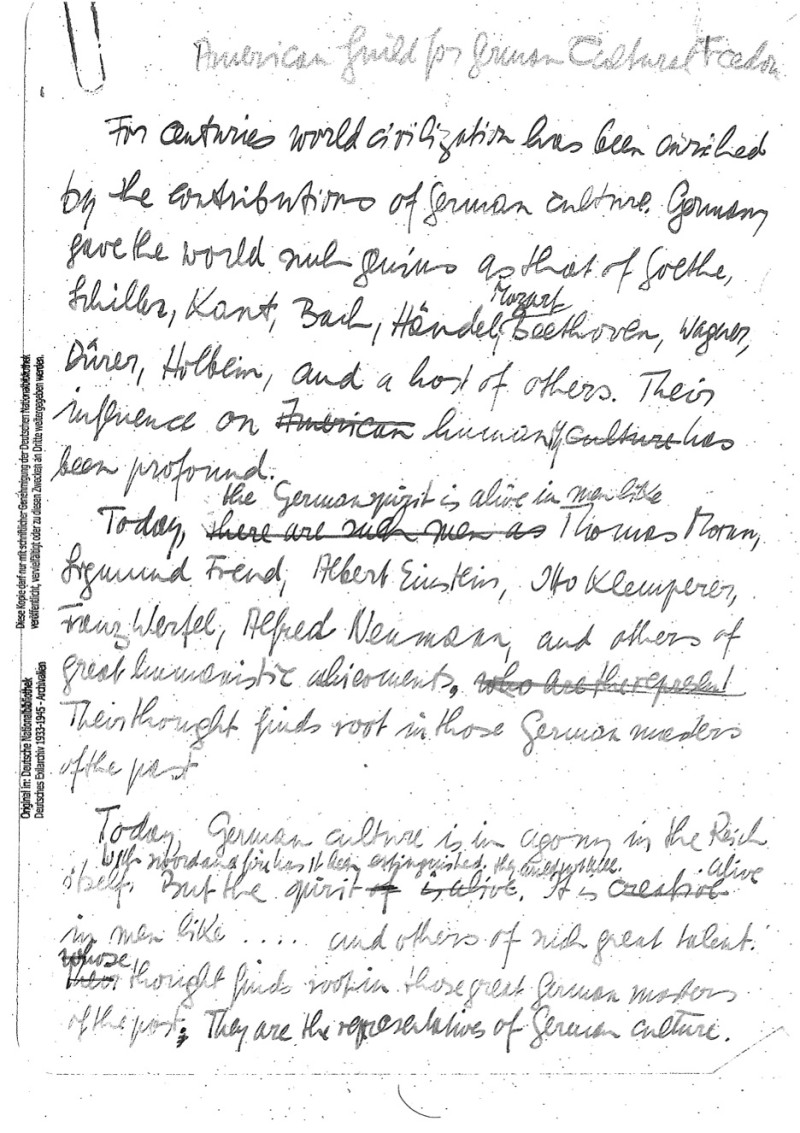

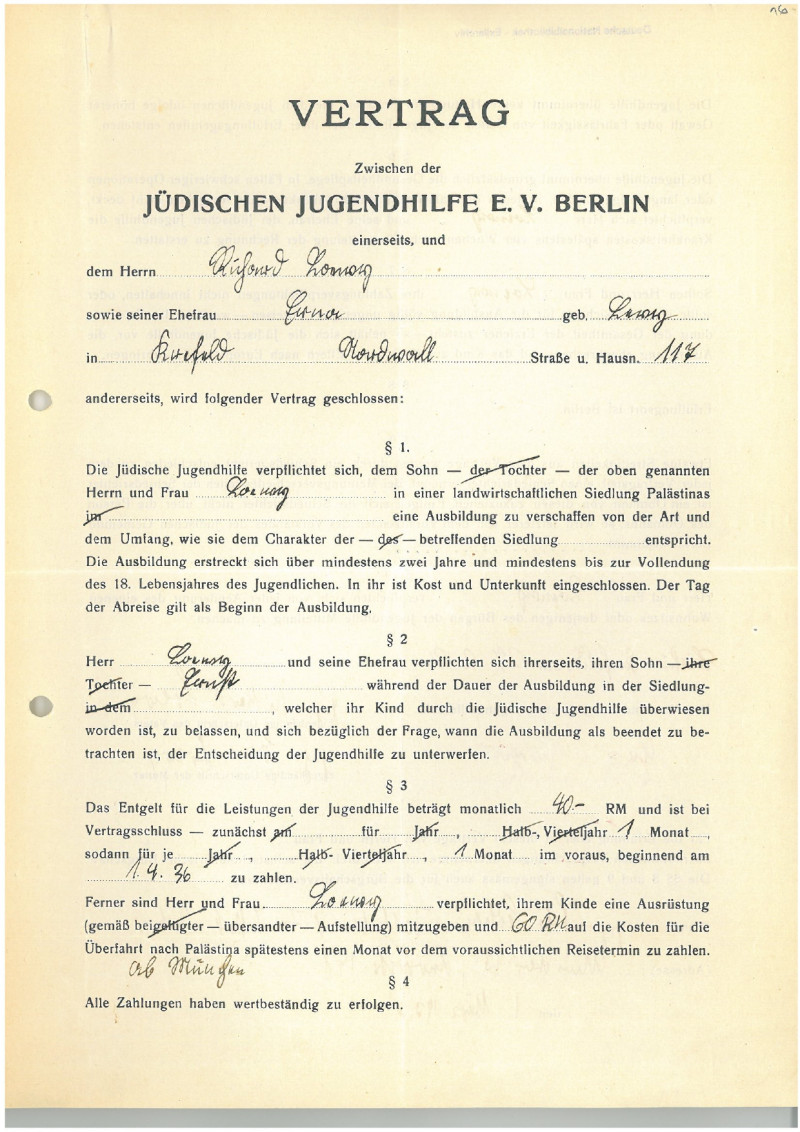

In order to arrive in a city and build a new life there, refugees usually need material, psychological and legal support, especially immediately after arrival. Since state support structures are often inadequate, a complex support network of local and global, state and non-state, institutional and informal actors in helping and self-helping refugees is developing.

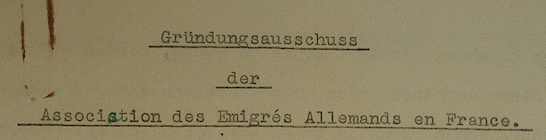

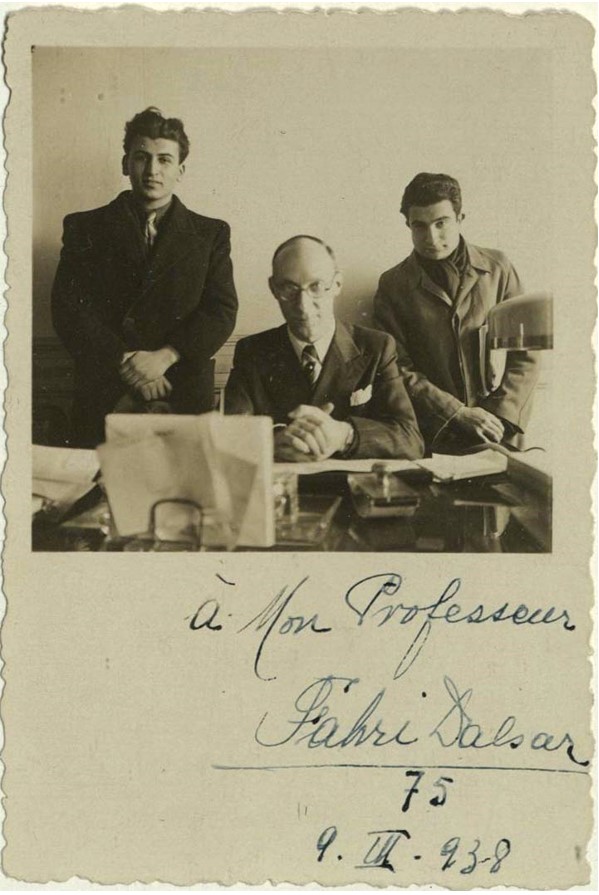

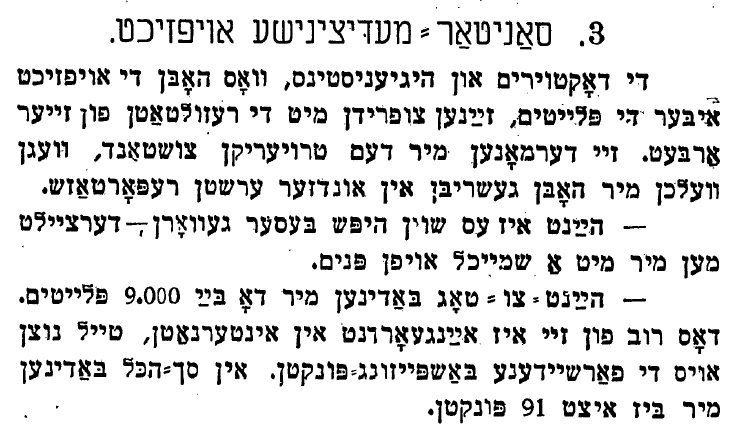

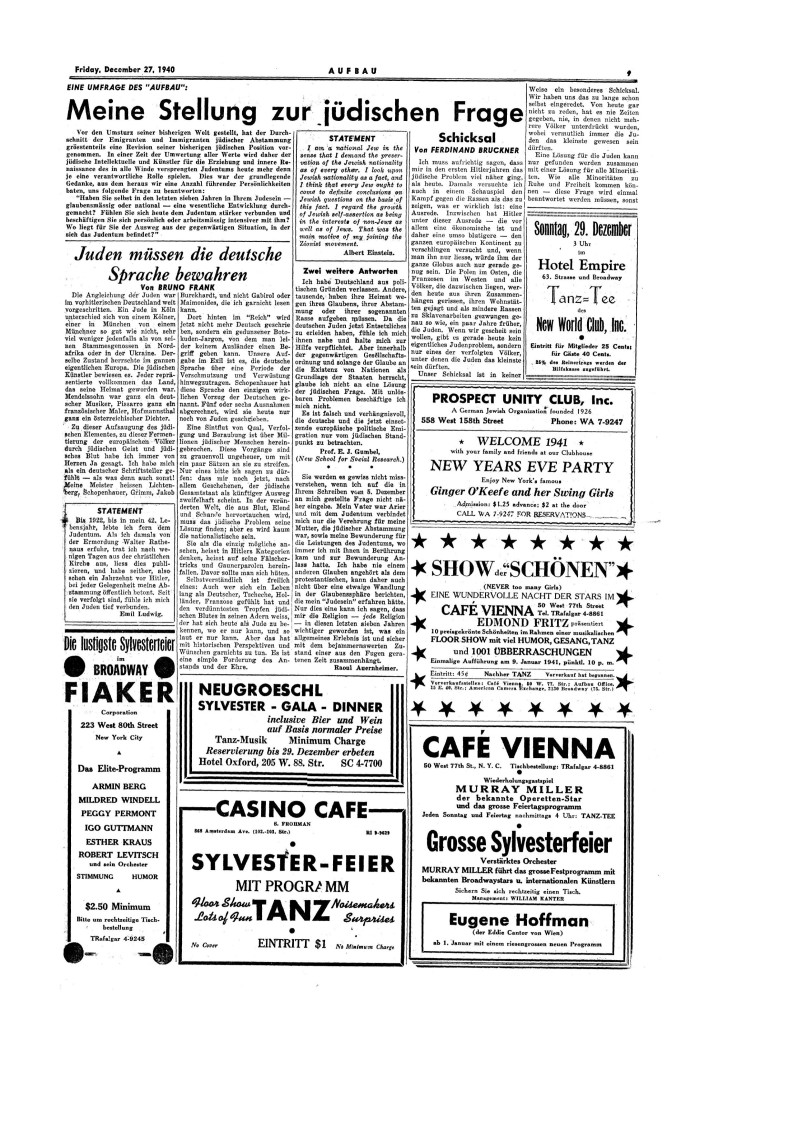

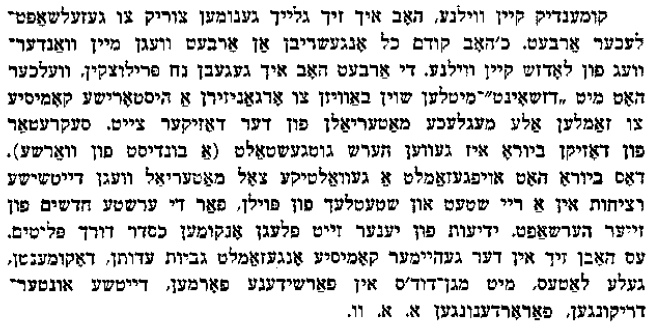

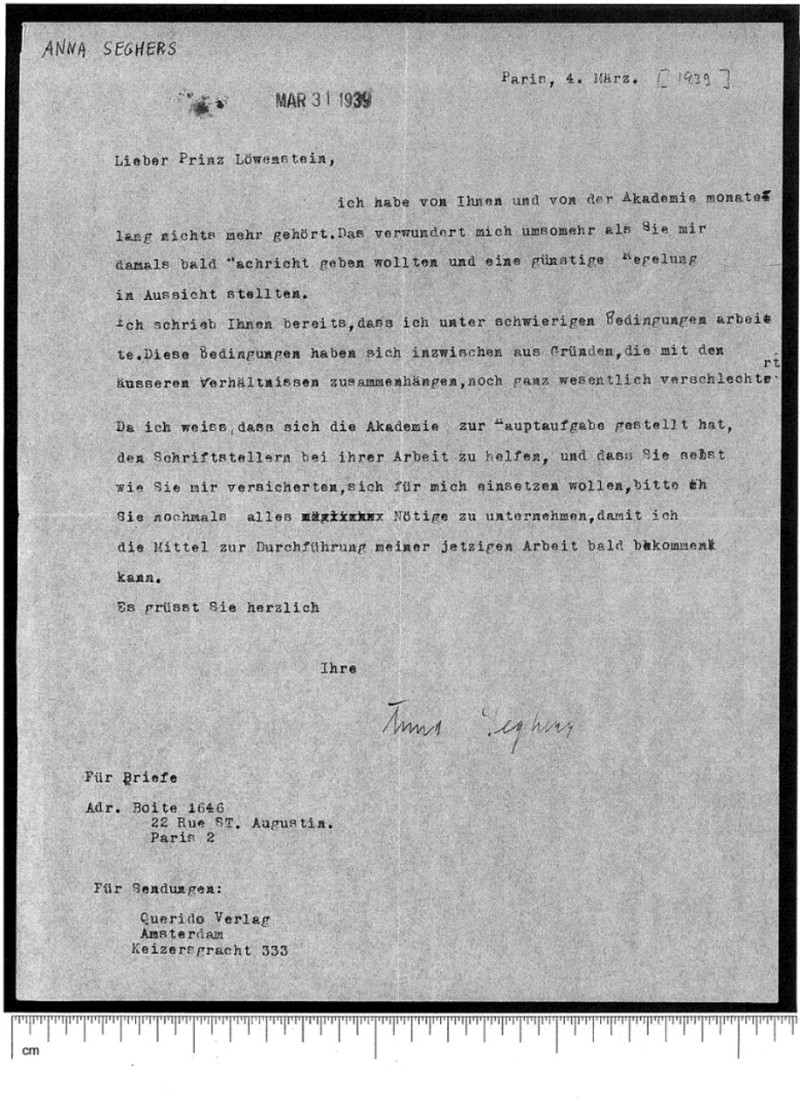

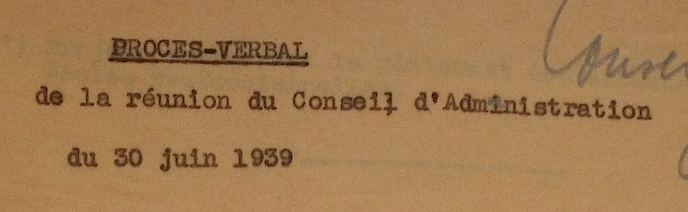

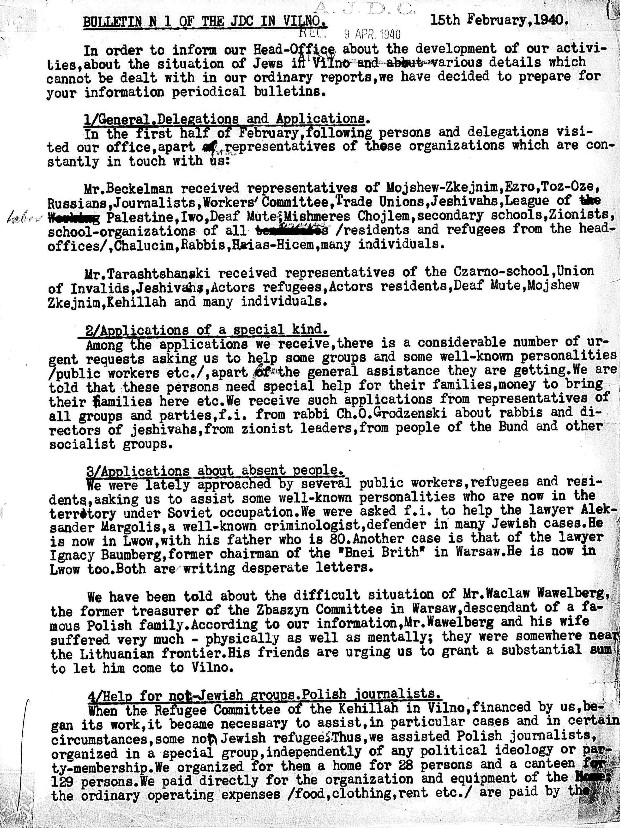

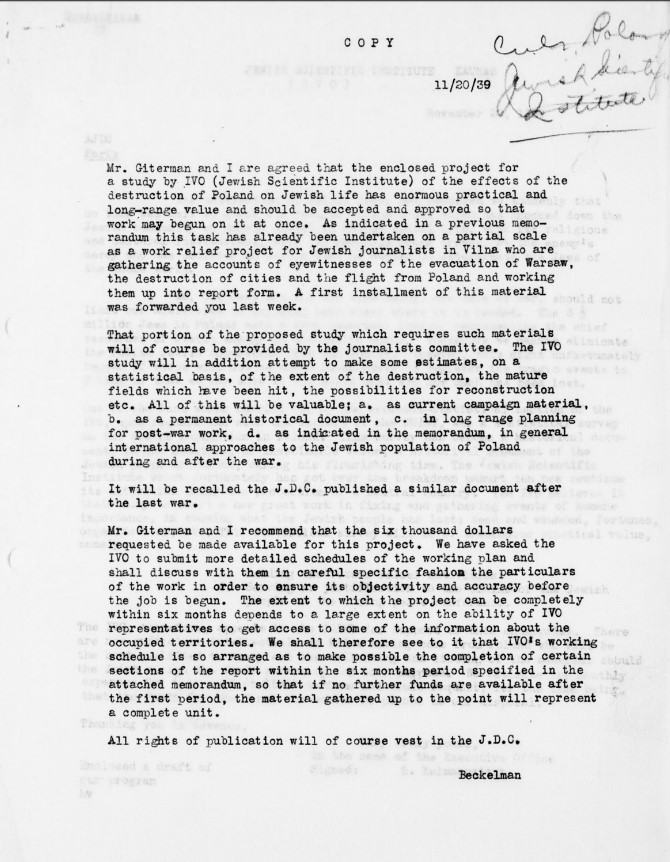

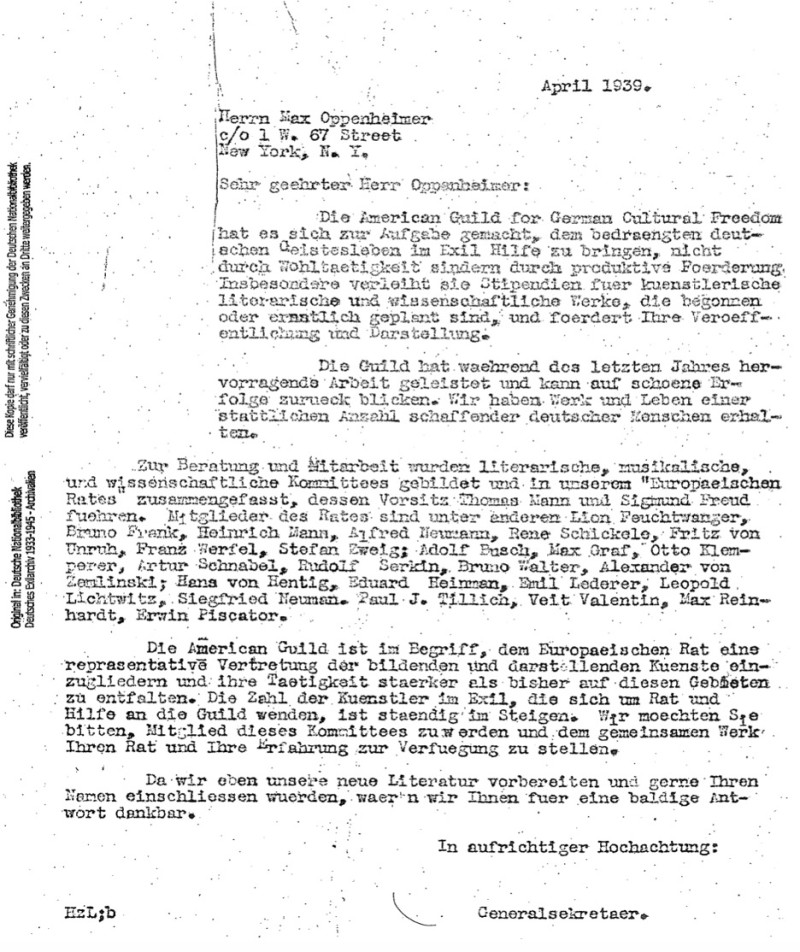

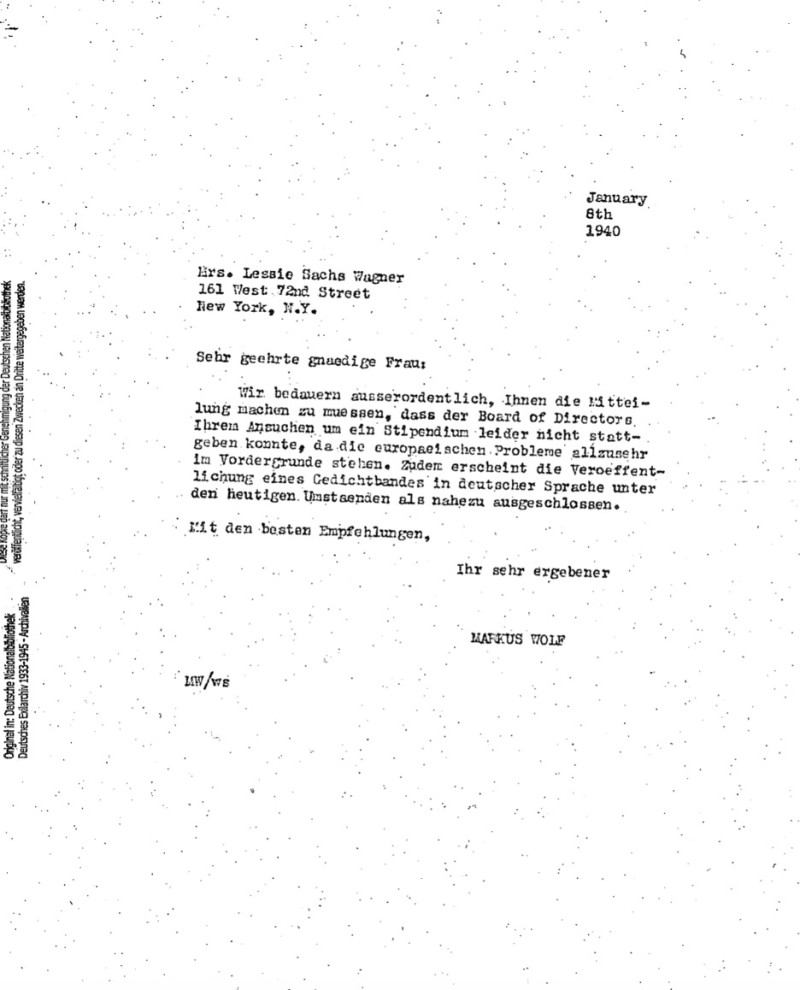

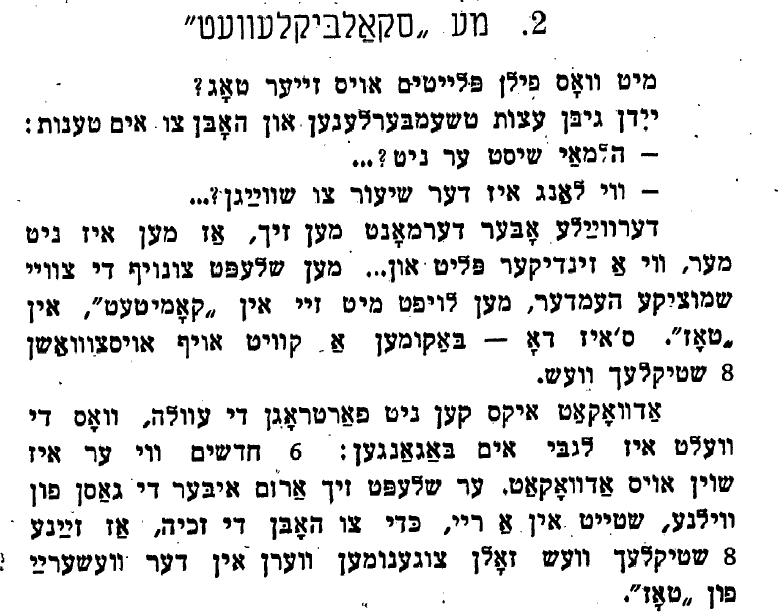

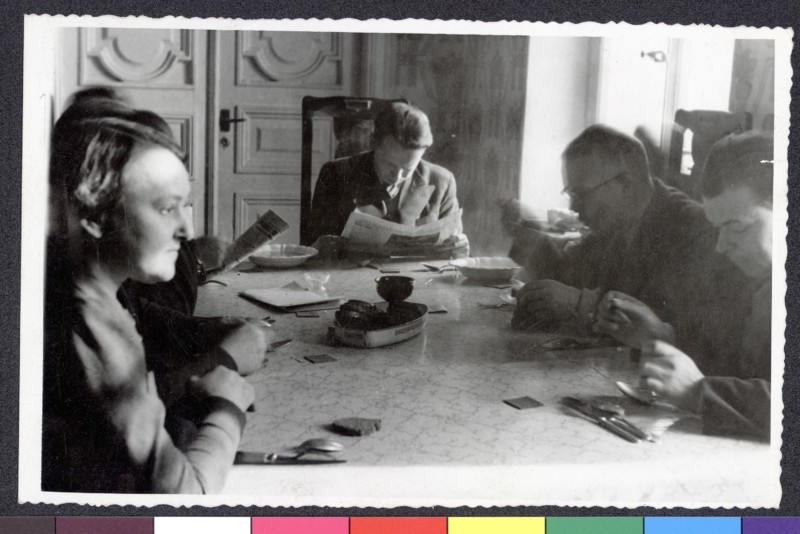

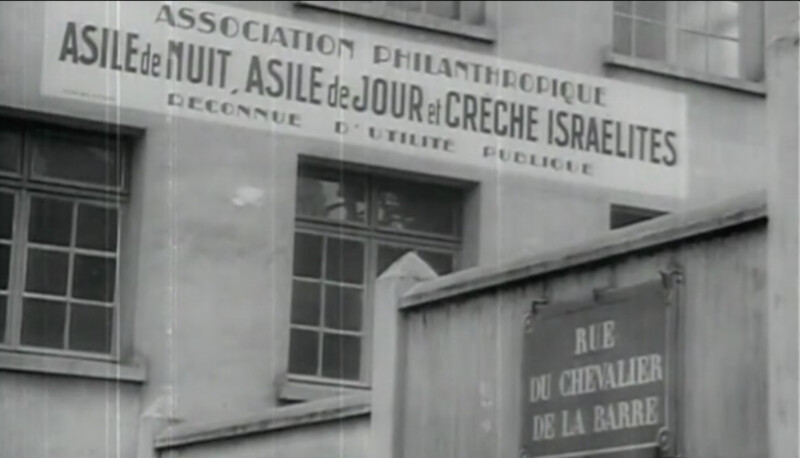

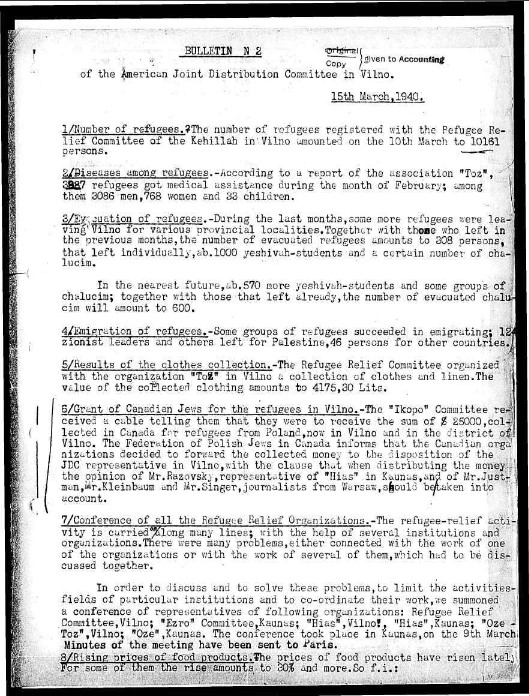

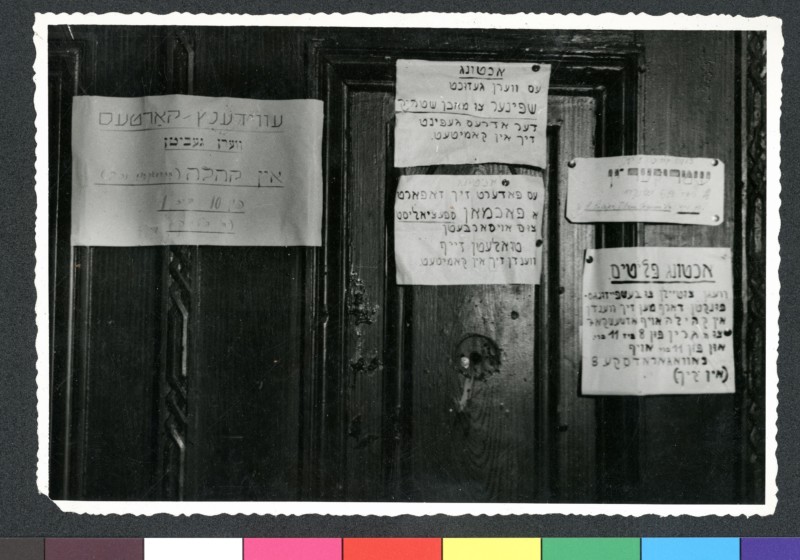

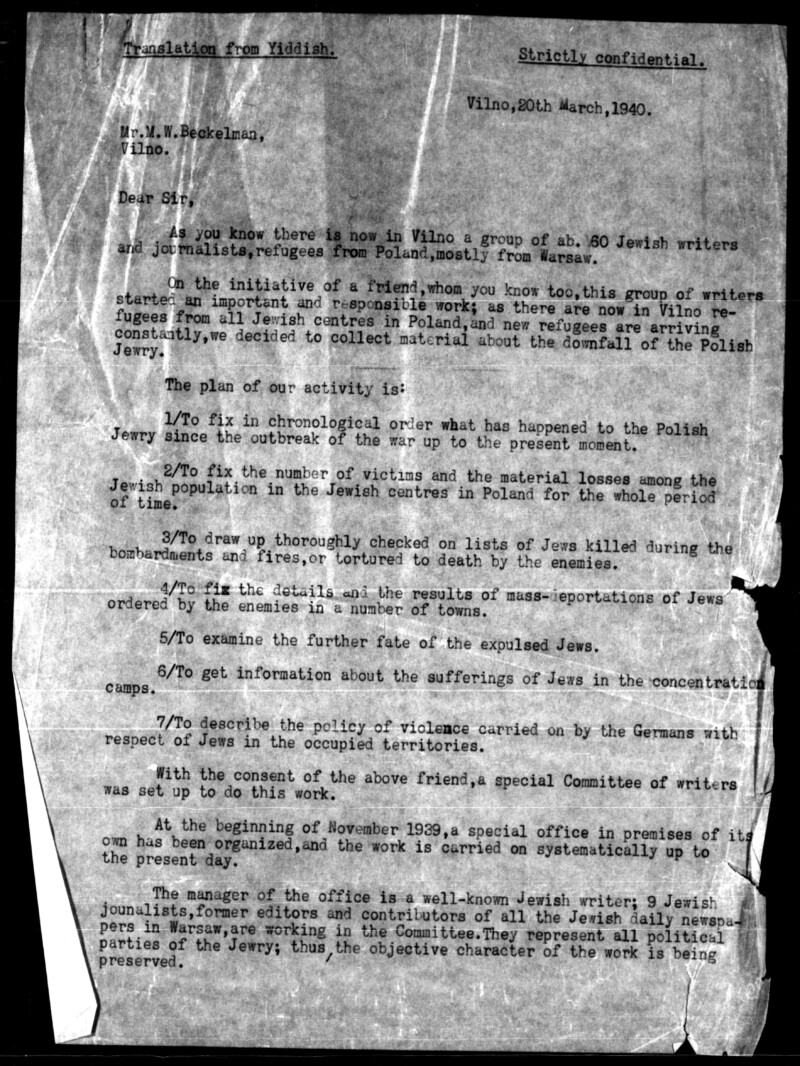

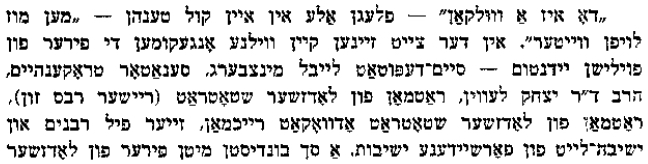

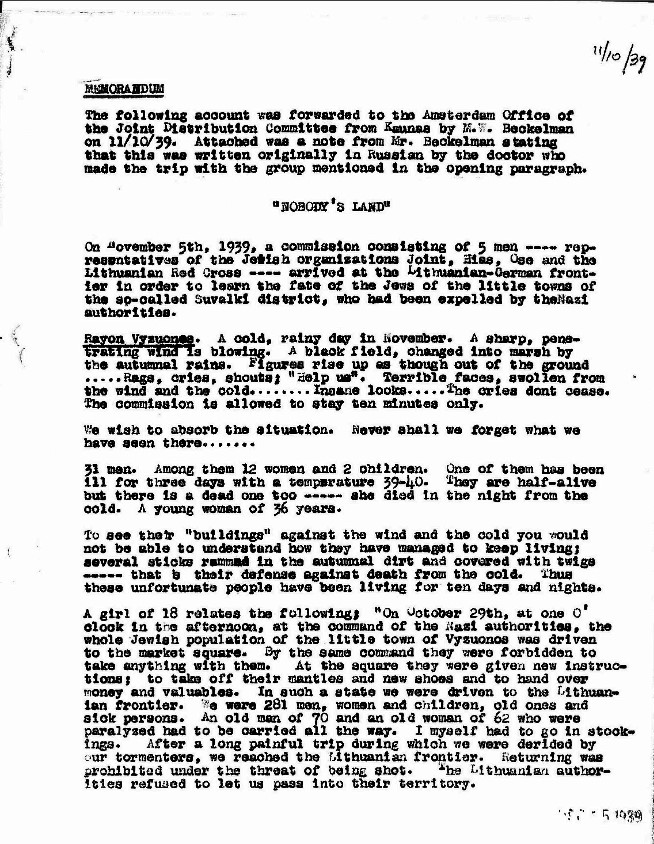

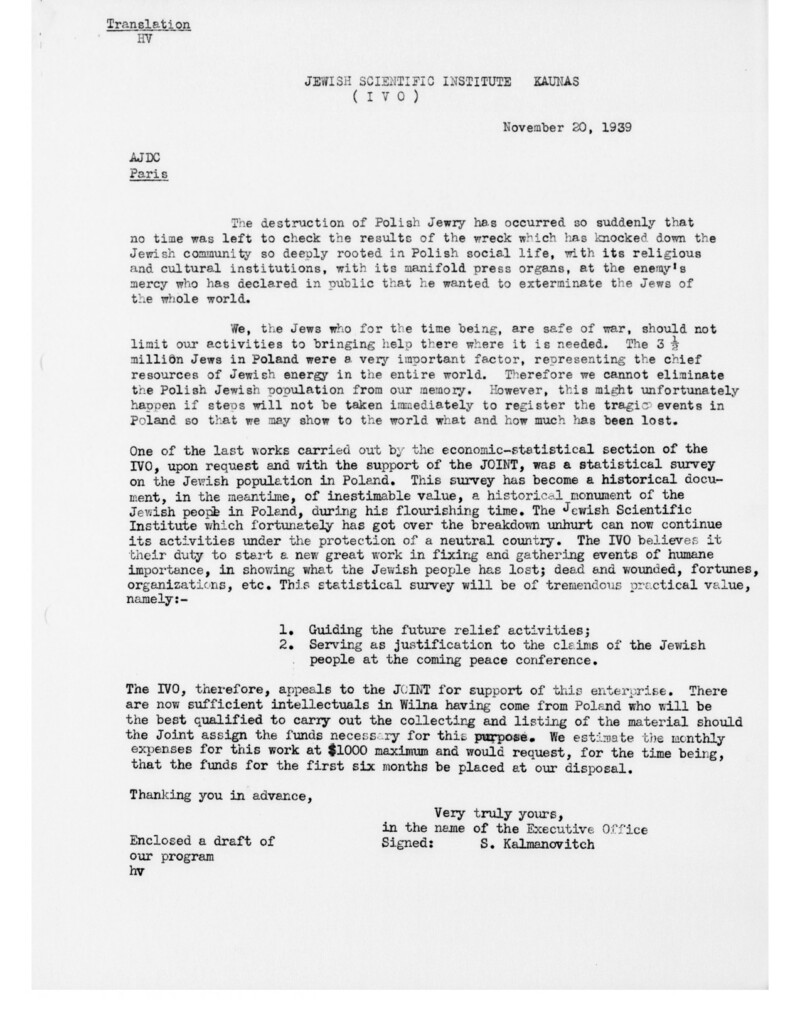

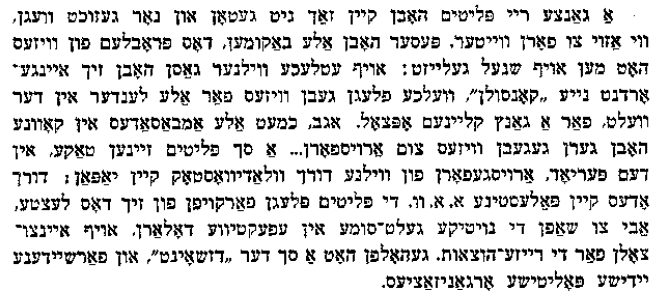

The example of the Polish-Jewish refugees in Vilnius illustrates the cooperation between Polish-Jewish and non-Jewish aid organisations, the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee and Jewish self-help in Vilnius, which was successfully coordinated by a committee.

“One can already say, that thanks to the Committee for Refugee Assistance of the Jewish Community of Vilnius, thanks to the financial support of the ‘Joint,’ thanks to the collaboration of TOZ in the field of healthcare – there is not a single hungry Jewish refugee in Vilnius, every refugee has an address, where he can go and sign up for supplies and where he has both clothing and housing assistance, medical care, legal assistance and if necessary also gets a professional training etc.”

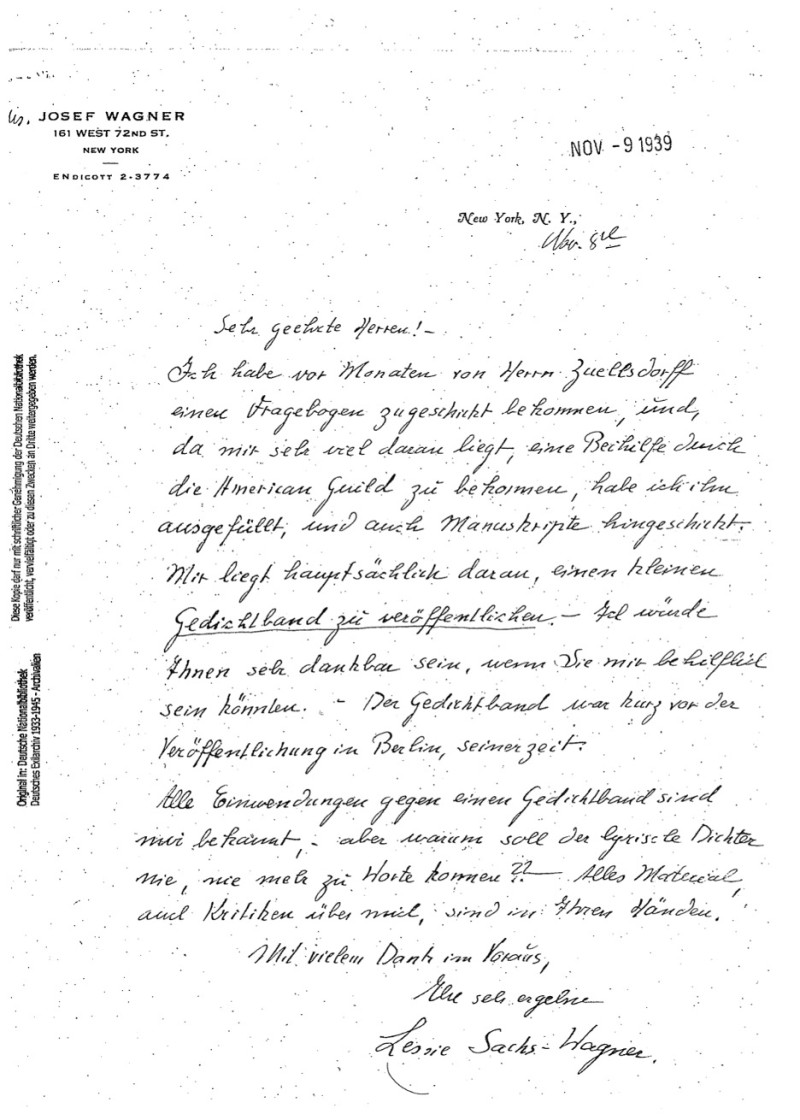

The importance of civil society support initiatives as well as networks, which bring together local politics and administration, churches, charities and civil society associations and groups is, almost 80 years later, still apparent. The cohesion of today’s existing networks is based on a joint effort for the sake of the human rights of refugees. This also connects the self-help structures to local support actors.

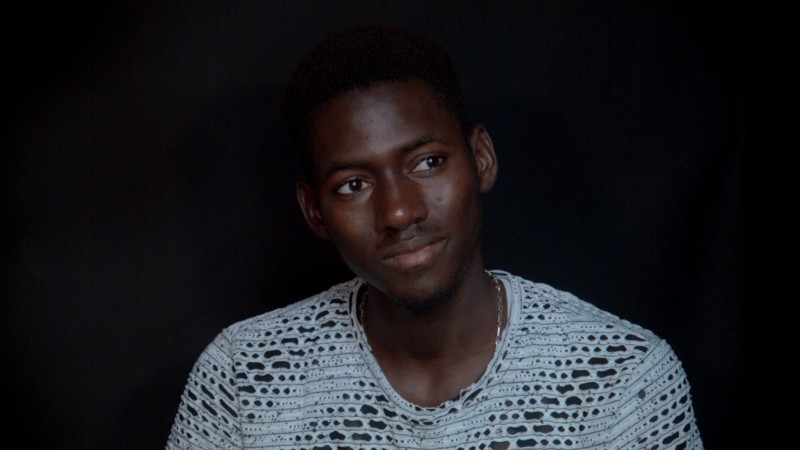

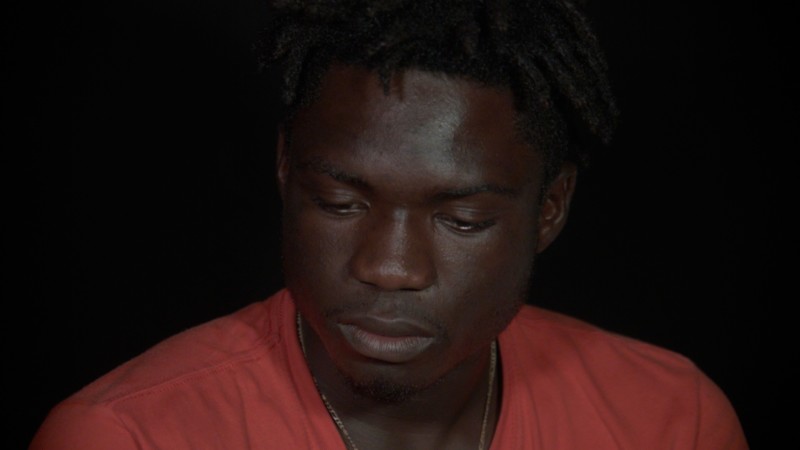

The city of Palermo exemplifies the enormous importance of local support structures in accommodating the significant number of underage refugees. Loneliness and self-reliance are a huge burden on these young people, as the We Refugees Archive participants in Palermo reported. There is often a lack of trusted persons who could provide them with an orienting framework. Individual people, groups or churches and civil society networks try to replace this at least partially.

The group of refugees included in the We Refugees Archive themselves have been active in Palermo since 2009: an example is the refugee collective Giocherenda, which was founded by underage refugees in Palermo in 2017. In addition to self-help, they are about giving something back to Europeans: “We want to help the Europeans” with games that strengthen solidarity and enable memory work through storytelling. In doing so, they also abolish a one-sided idea of refugees as mere recipients of support and instead represent a positive, powerful migrant self-image that contributes to social cohesion.