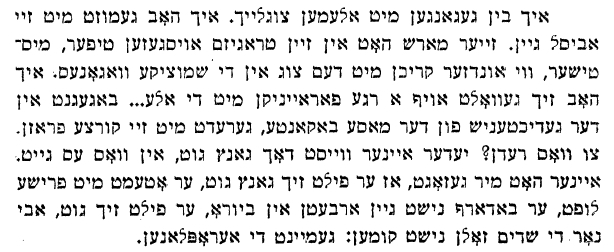

“Our identity is changed so frequently that nobody can find out who we actually are.”

Identity is by nature individual and diverse, constantly changing reinventing itself. It is always the sum of various complementary, contradictory, refractive and continuous influences. This applies to every human being, whether a refugee or not.

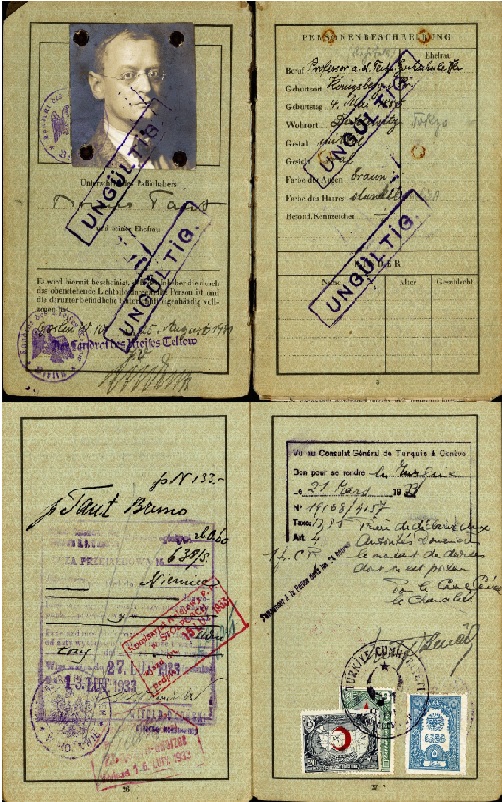

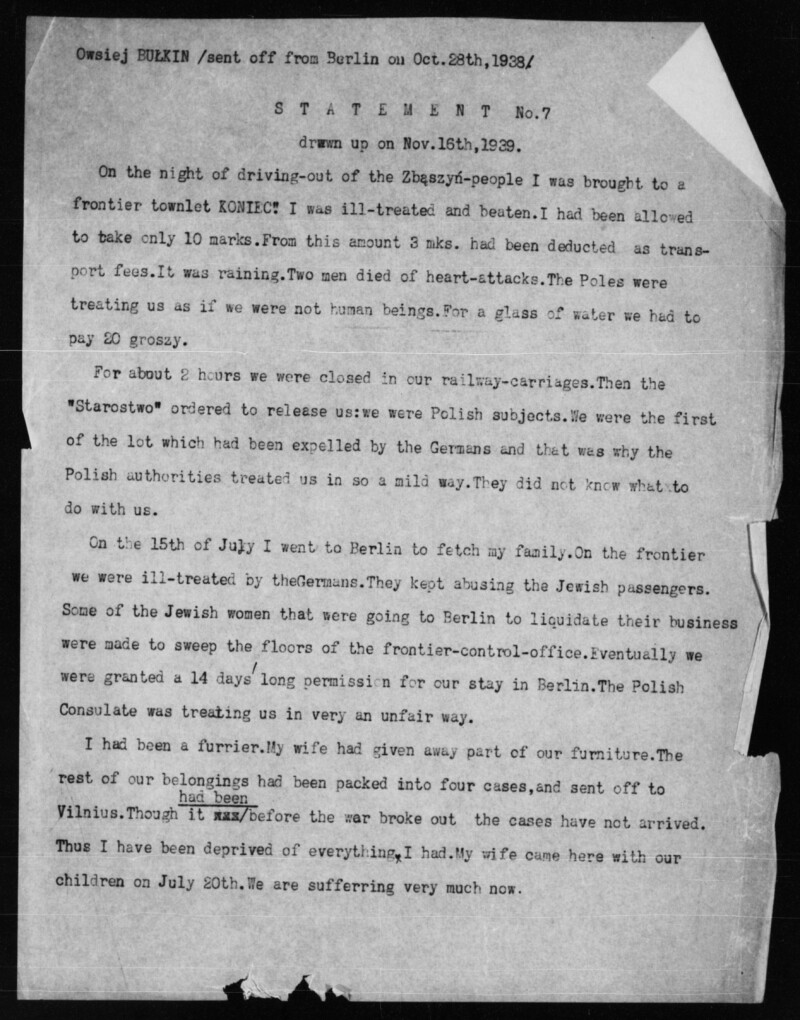

For most people, however, forced migration means a life-changing rupture. This rupture, the lasting effect of which has a decisive impact on life at the place of new beginnings, binding it permanently to the experience of flight and to the people, habits, places and language(s) one has left behind. It is usually intensified by the fact that the desire for recognition and belonging and the obligation to assimilate into the majority society of the place of refuge is usually accompanied by a (partial) loss of the social status or even personality, for which one was regarded and respected before the flight. At the point of arrival, people often lose control over who the environment considers them to be.

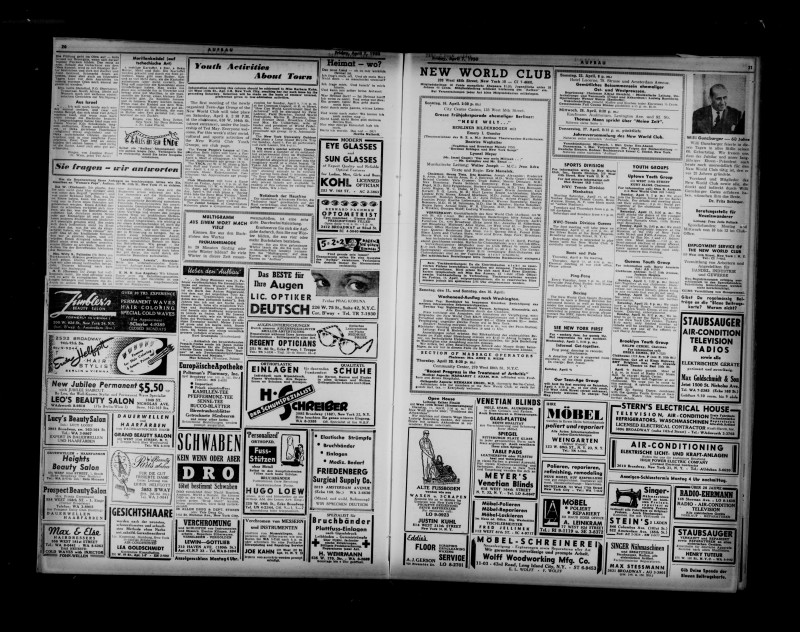

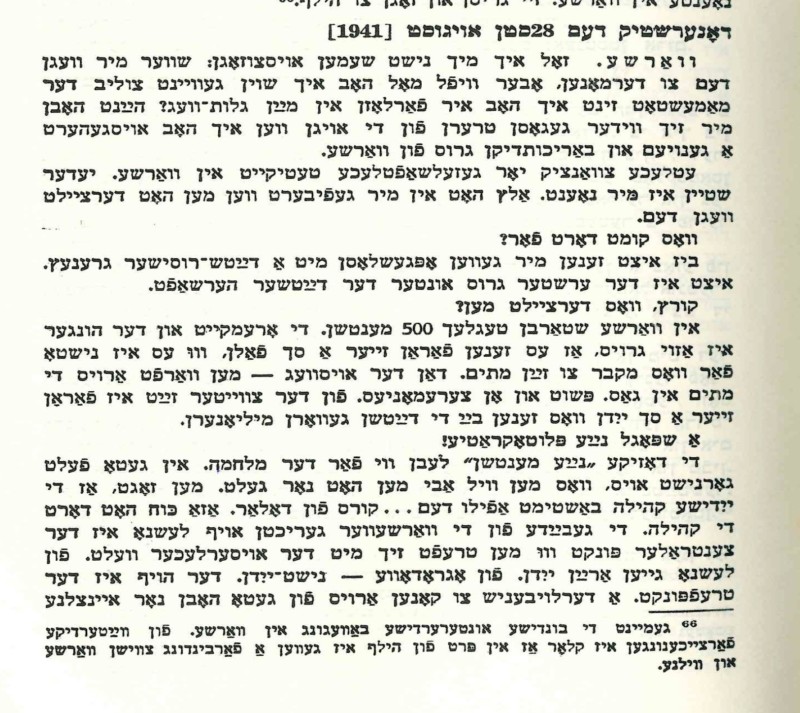

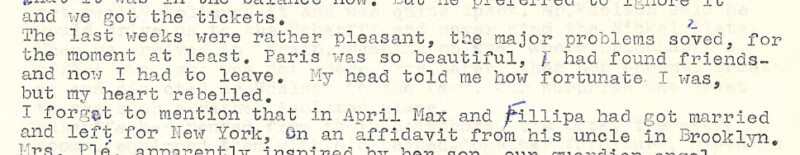

So while refugees then and now try to build a new life for themselves, it was seldom possible to tie in seamlessly with what had been created and built up before. More serious than the loss of status, job and property is for most people the separation from family, friends and often also the uncertainty about their loved ones’ and their own fate. Isolation and loneliness, along with the often traumatic experiences of flight and the insecure situation in which one finds oneself even after arrival, contribute to a high level of psychological stress.

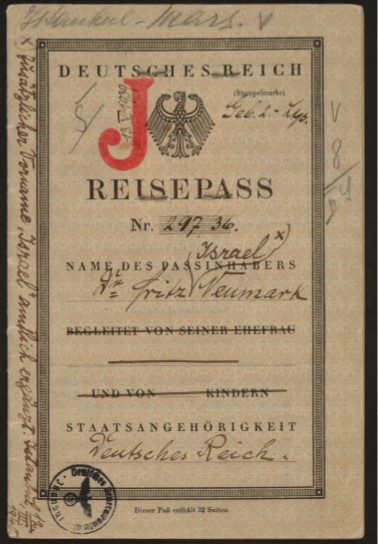

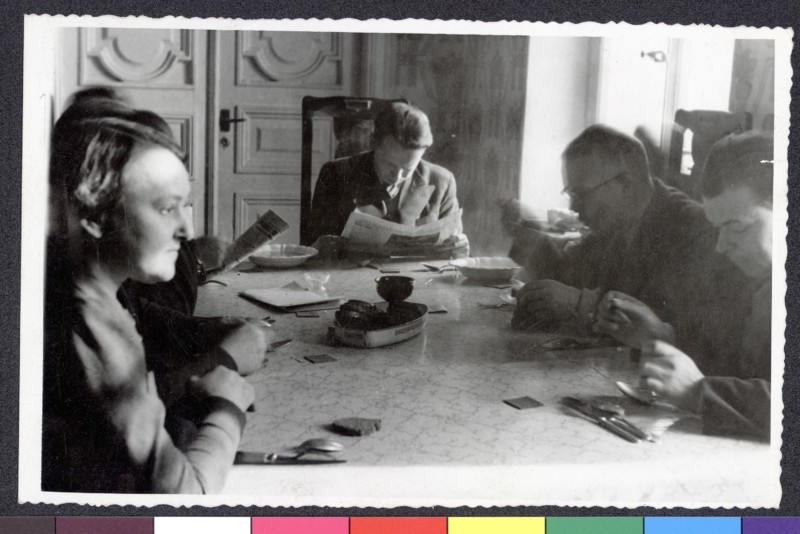

Fleeing from Nazi persecution, Jewish people often were not always able to stay with their families due to great haste or inhuman migration regimes. Also today, many people are separated from their families by forced migration and often know nothing about their whereabouts. This situation is particularly precarious for children who are fleeing without adult family members.

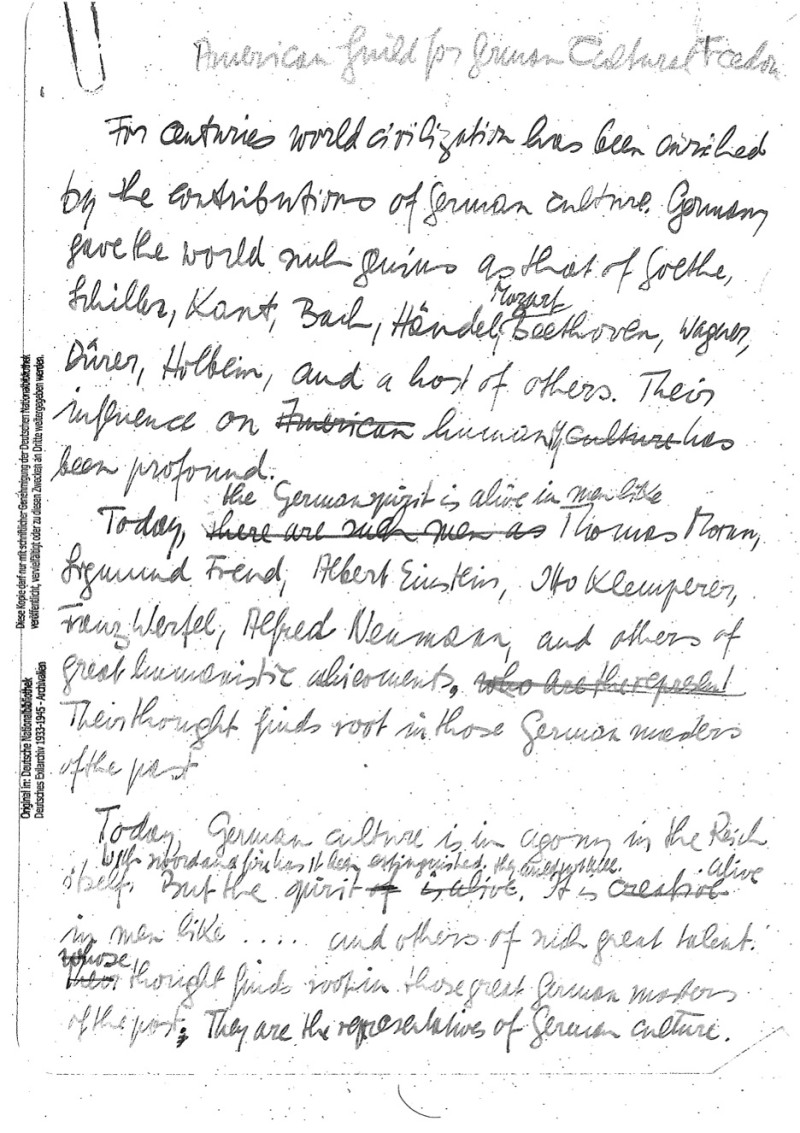

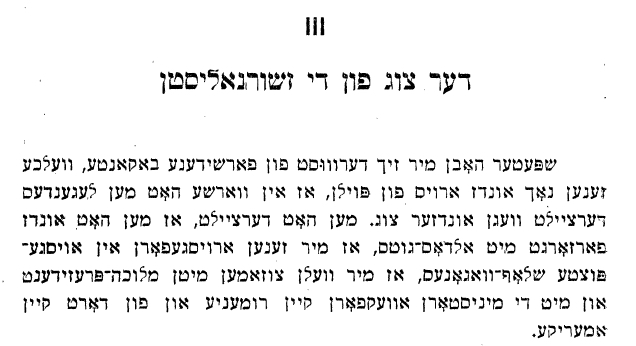

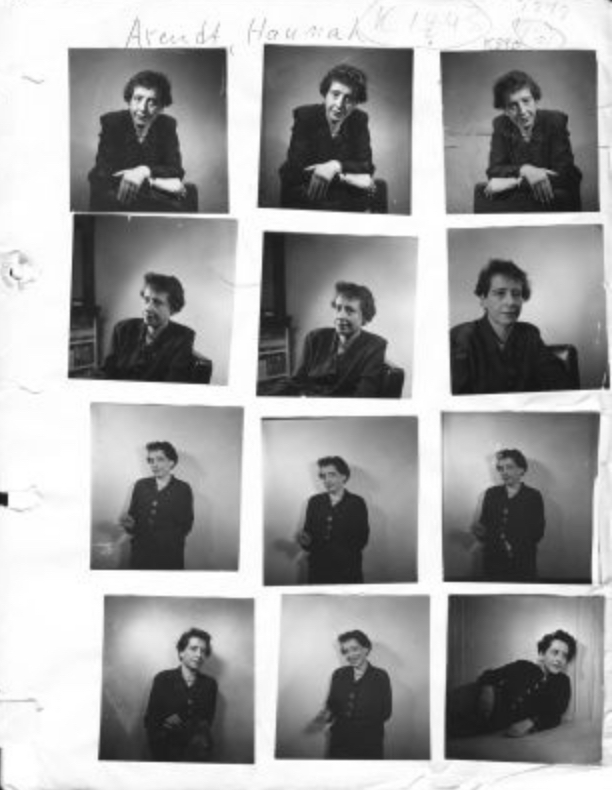

“We lost our home, which means the familiarity of daily life. We lost our occupation, which means the confidence that we are of some use in this world. We lost our language, which means the naturalness of reactions, the simplicity of gestures, the unaffected expression of feelings. We left our relatives in the Polish ghettos and our best friends have been killed in concentration camps, and that means the rupture of our private lives.”

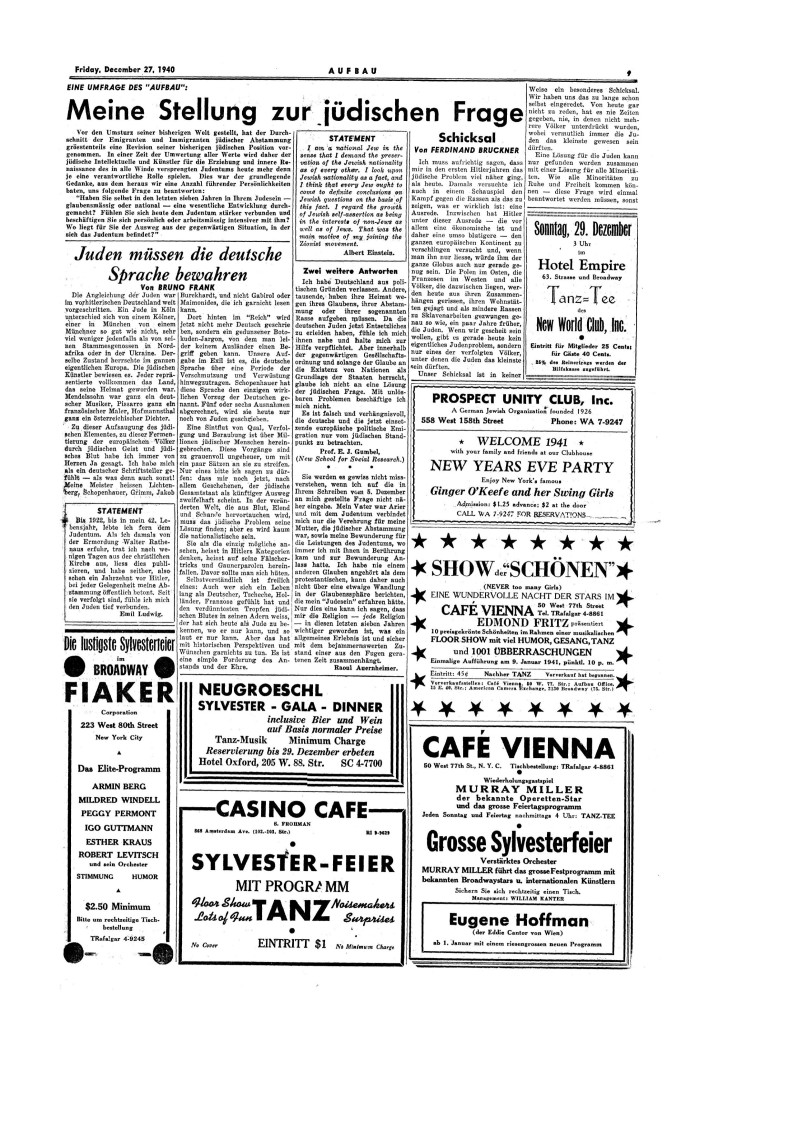

Any approach to questions of refugee identities must face the task of analyzing the reciprocal dynamics between migrant self-image and (racist, antisemitic and misogynist) alienation, as well as between the perceived identities of refugees and the structural and systemic disenfranchisement, discrimination and integration dictates from outside, which (may) stand in the way of personality development.

“In the first place, we don’t like to be called ‘refugees’.”

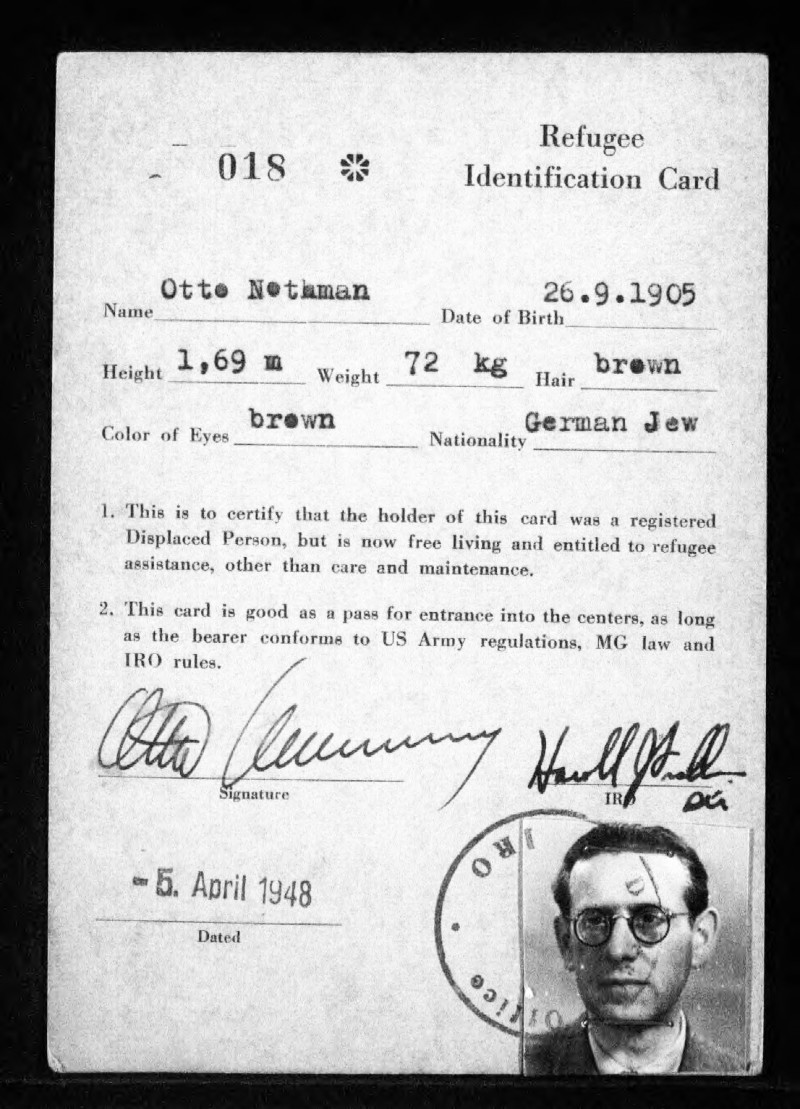

To be reduced to a migrant identity and the respective immigration status often results in situations where people find themselves in the precarious situation of both having lost their past and looking in an uncertain future. For Jewish refugees as well as for refugees today this meant/means that a secure stay at a location was/is never entirely certain. While Jewish refugees lived with the fear that their places of refuge will be occupied by Nazi Germany and thereby turns life-threatening for them, refugees in Europe today fear deportation back to dangerous countries of origin or transit. Their own efforts for participation in the society and for building their lives anew play only a minor role in their decisions to stay in a place. But not only do laws exclude refugees from full participation in social life, many experience discrimination in everyday life. Many try to evade this rejection by constantly adapting to new norms.

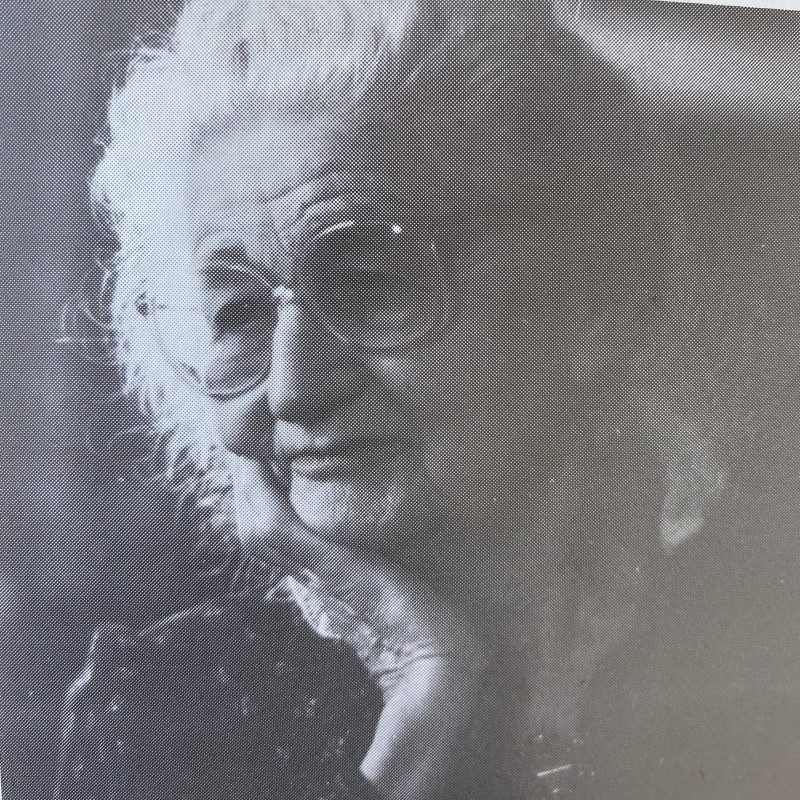

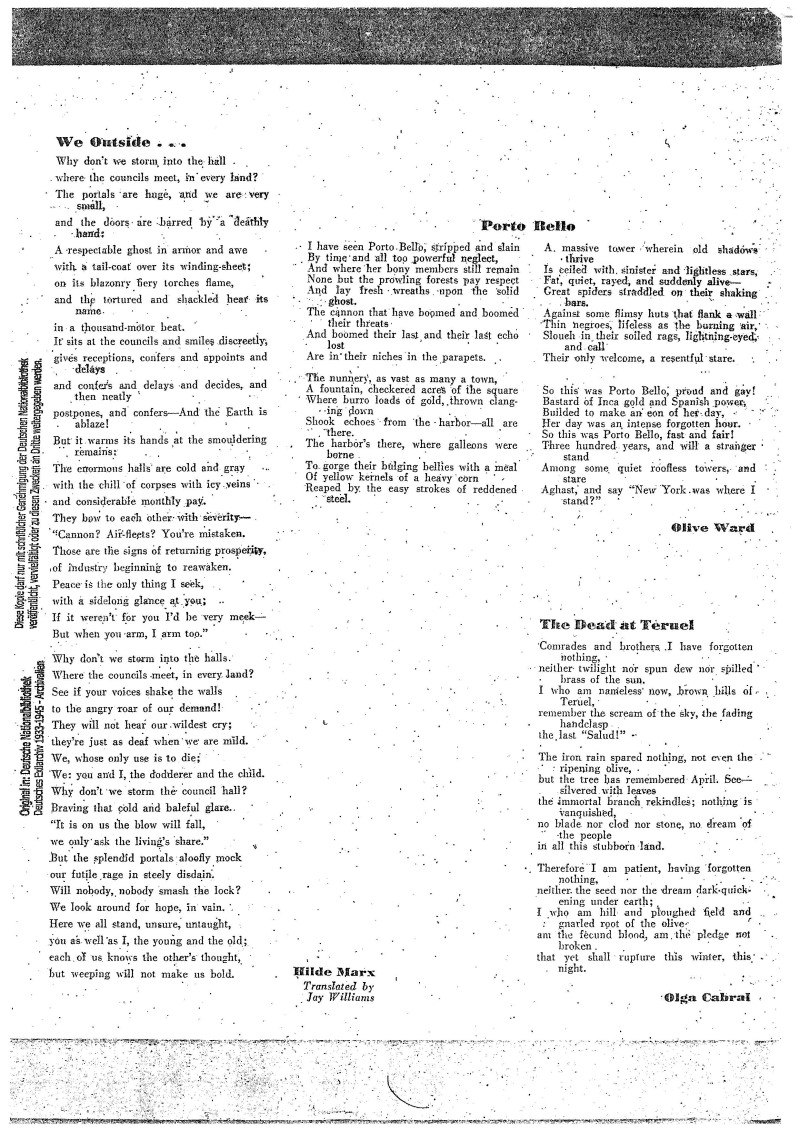

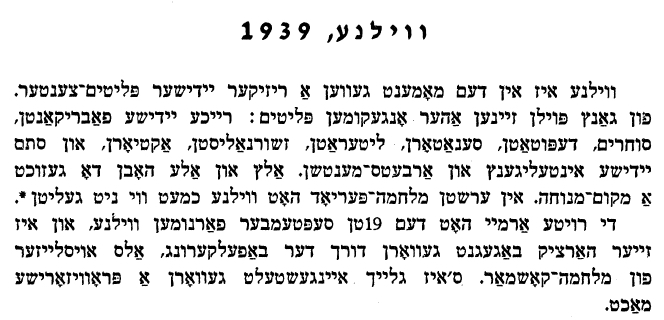

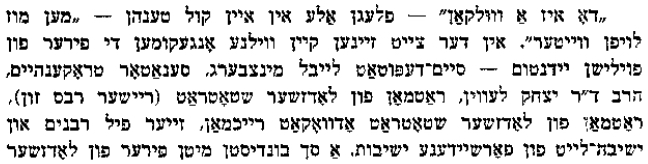

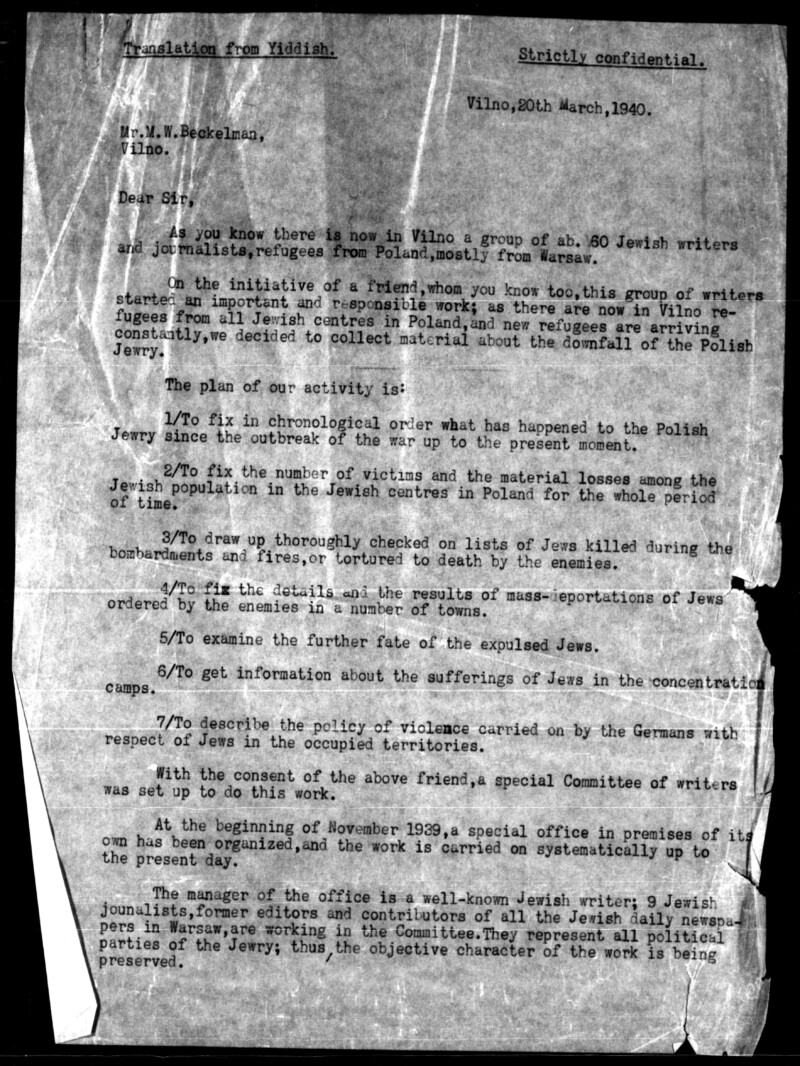

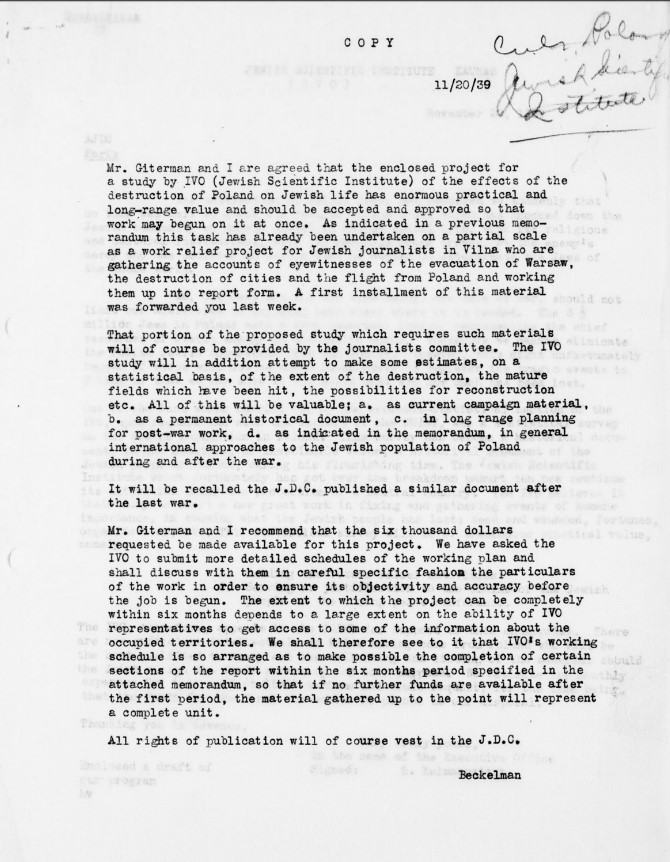

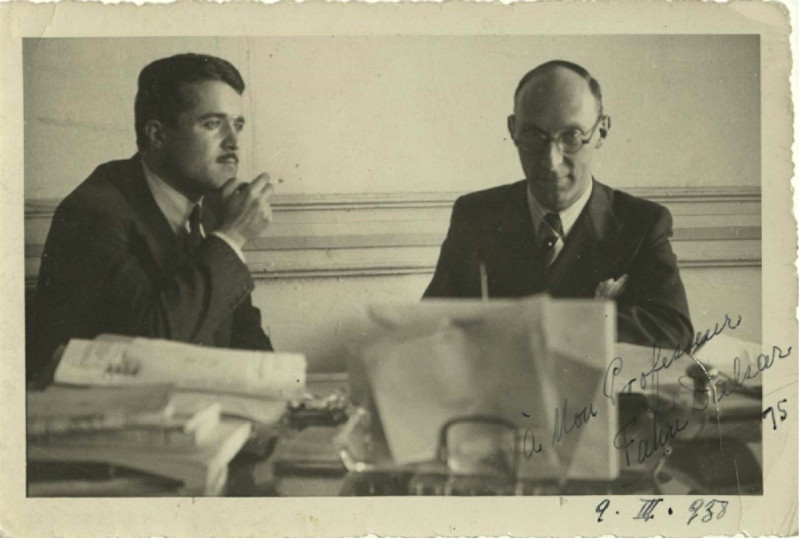

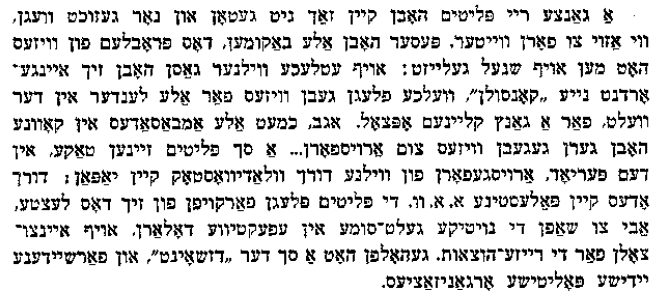

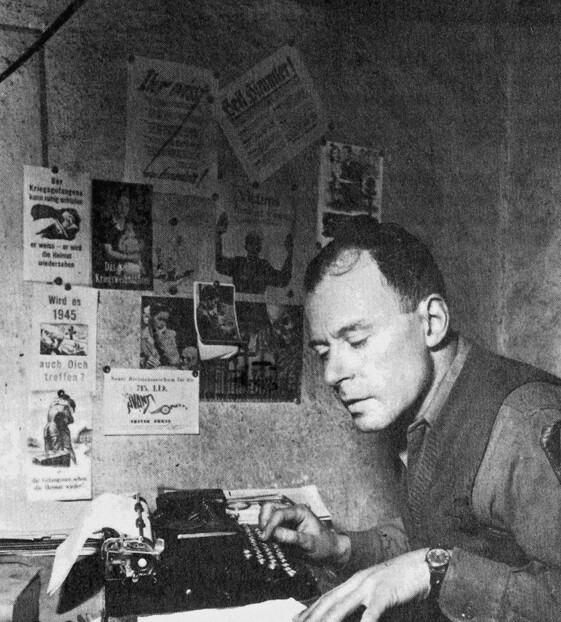

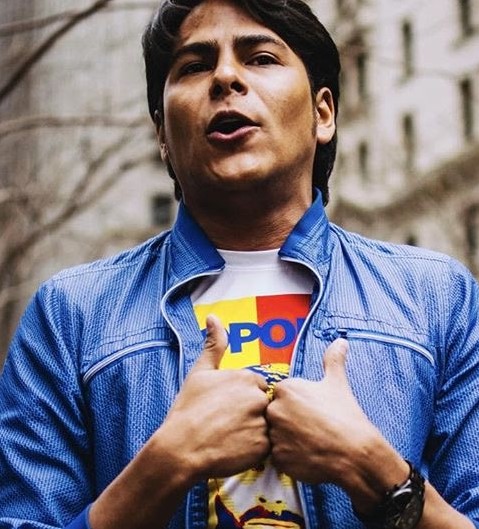

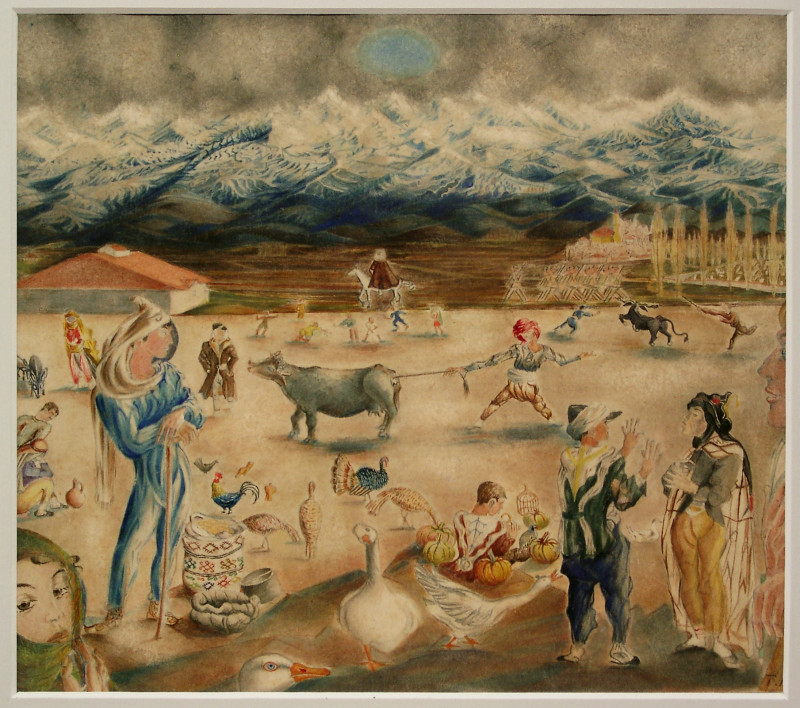

However, flight is not a one-way street and trauma is not an inevitable and insurmountable break. To counter this subjection and to regain a self-defined identity and recognition as a person and as a personality, refugees attempt to engage by exhibiting their own, positive self-image as a person active in society. They make their voice heard and demand attention for themselves – just as the participation in the workshop in Palermo. And they hope for being recognized and heard, for being remembered. For Jewish refugees of the past, this hope for remembrance was so crucial that they began early on to document expulsion and extermination in a self-organized fashion. Also today, refugees form organizations for the sake of becoming politically mature and of standing in for their demands externally by using creative ways of self-expression.

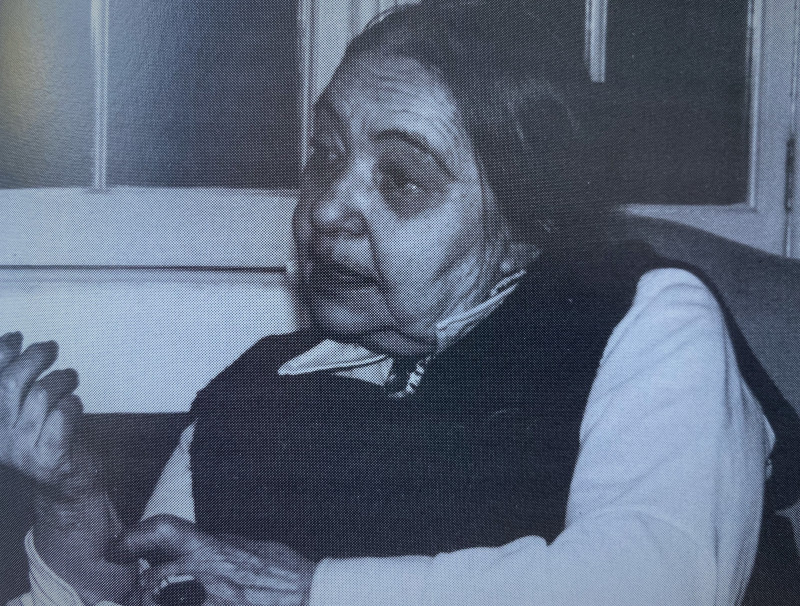

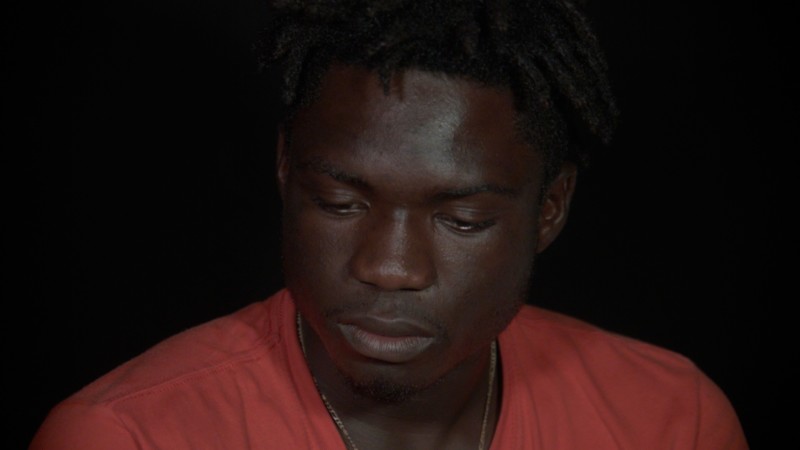

In this thematic bloc, people talk about the ruptures in their lives, about who they previously were and what they still want to be, from experiences of discrimination, homesickness and pain, and of their self-understanding. Although these topics are very personal, questions of the structural causes of rupture are always in the background, as is the question of the very meaning of testimony.