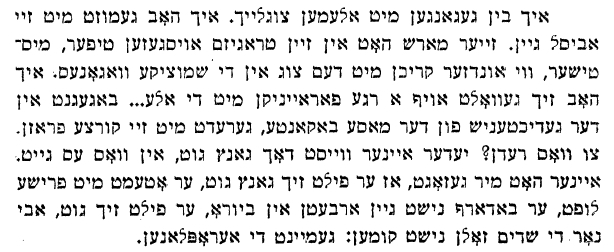

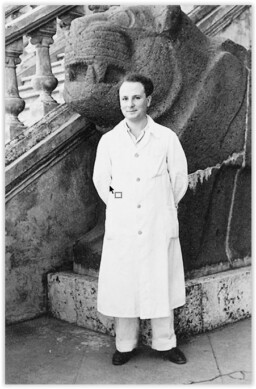

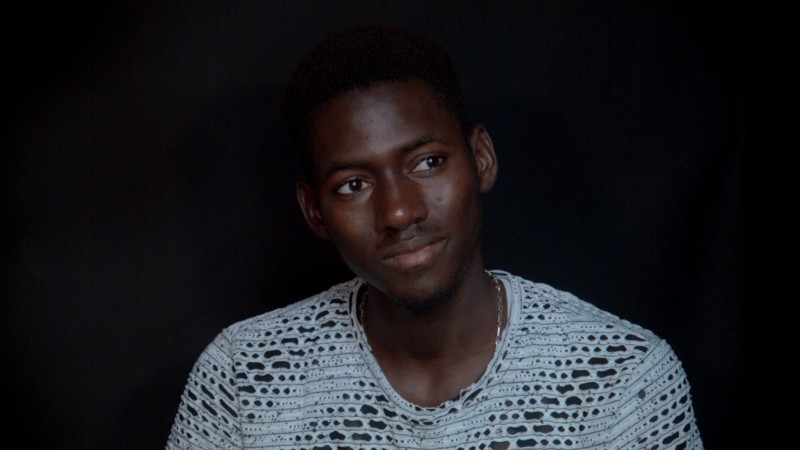

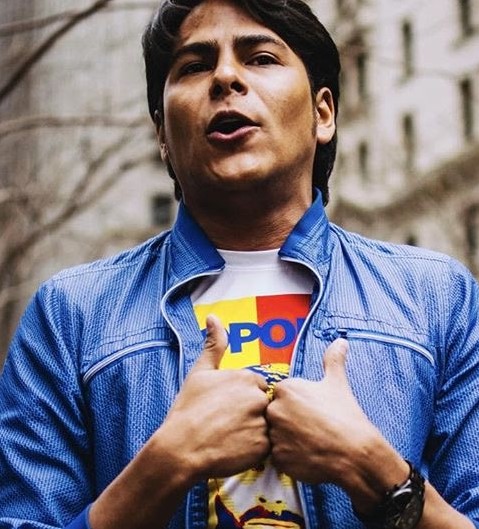

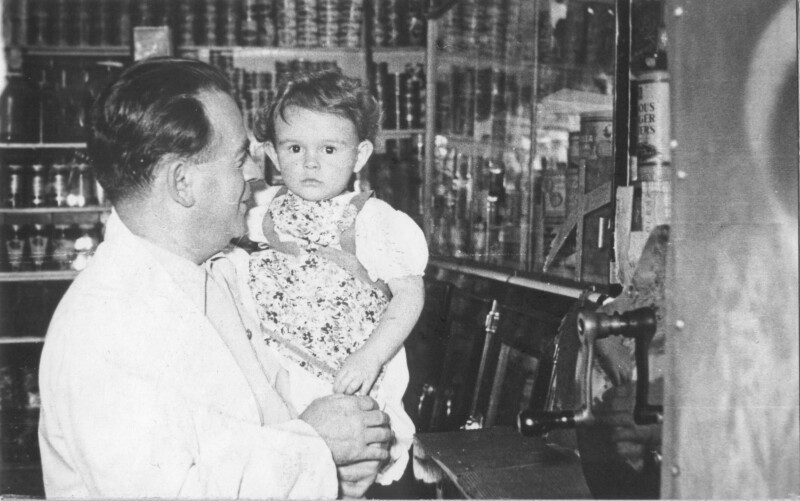

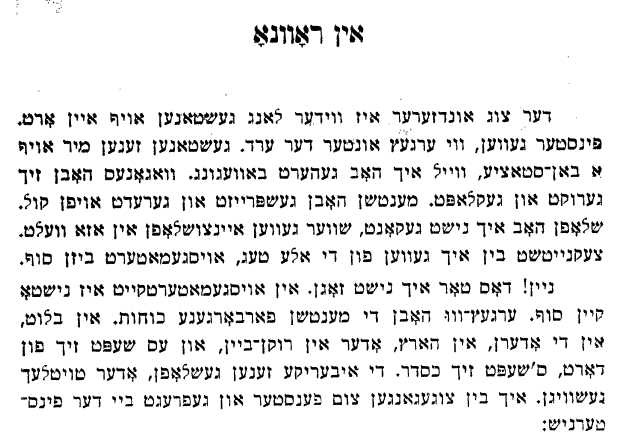

“In order to rebuild one’s life one has to be strong and an optimist.”

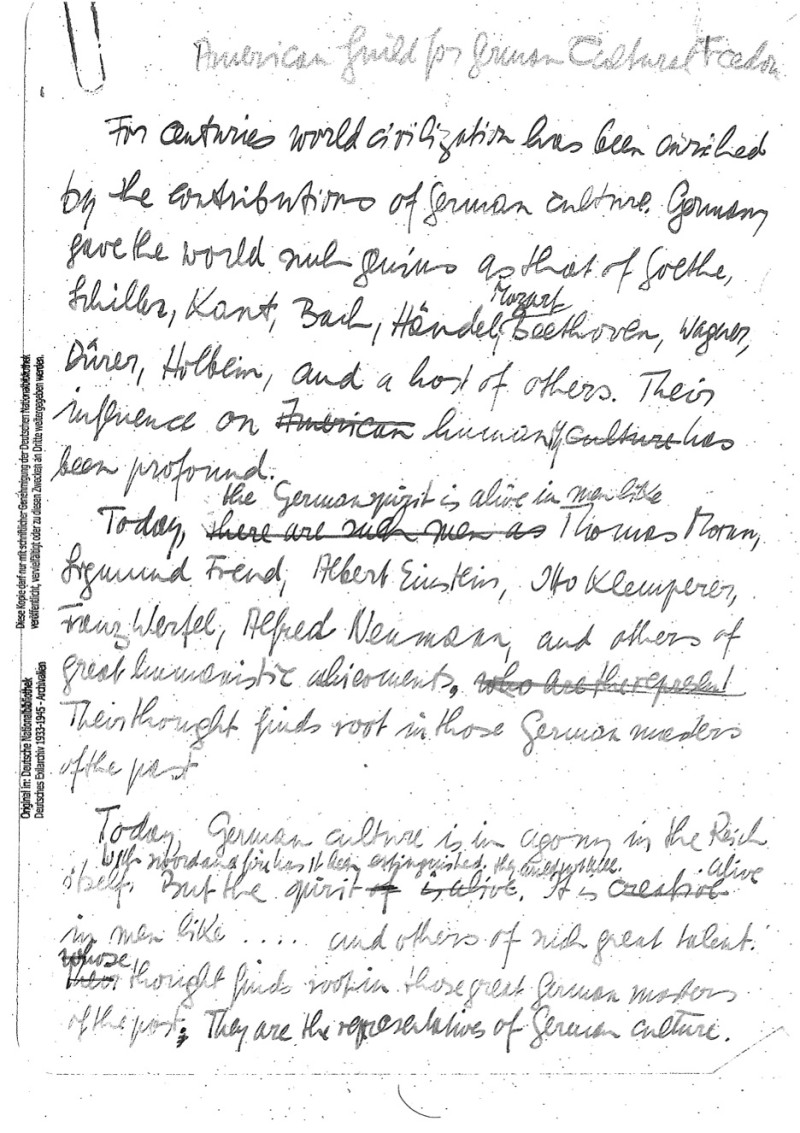

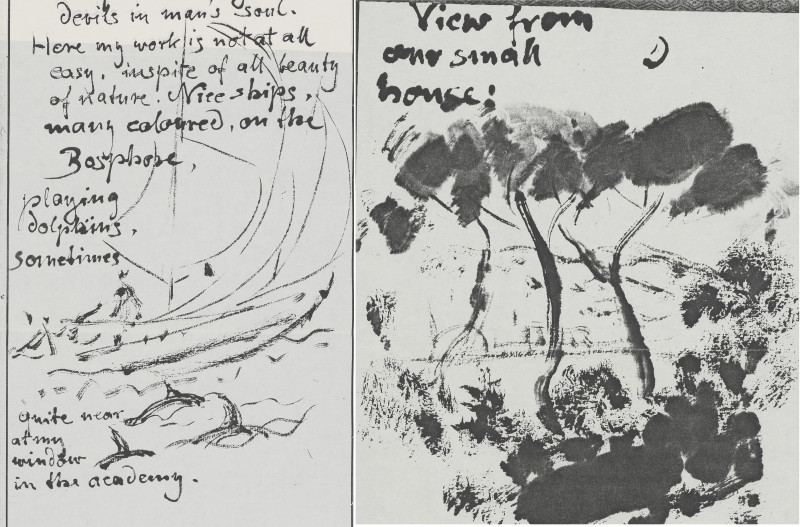

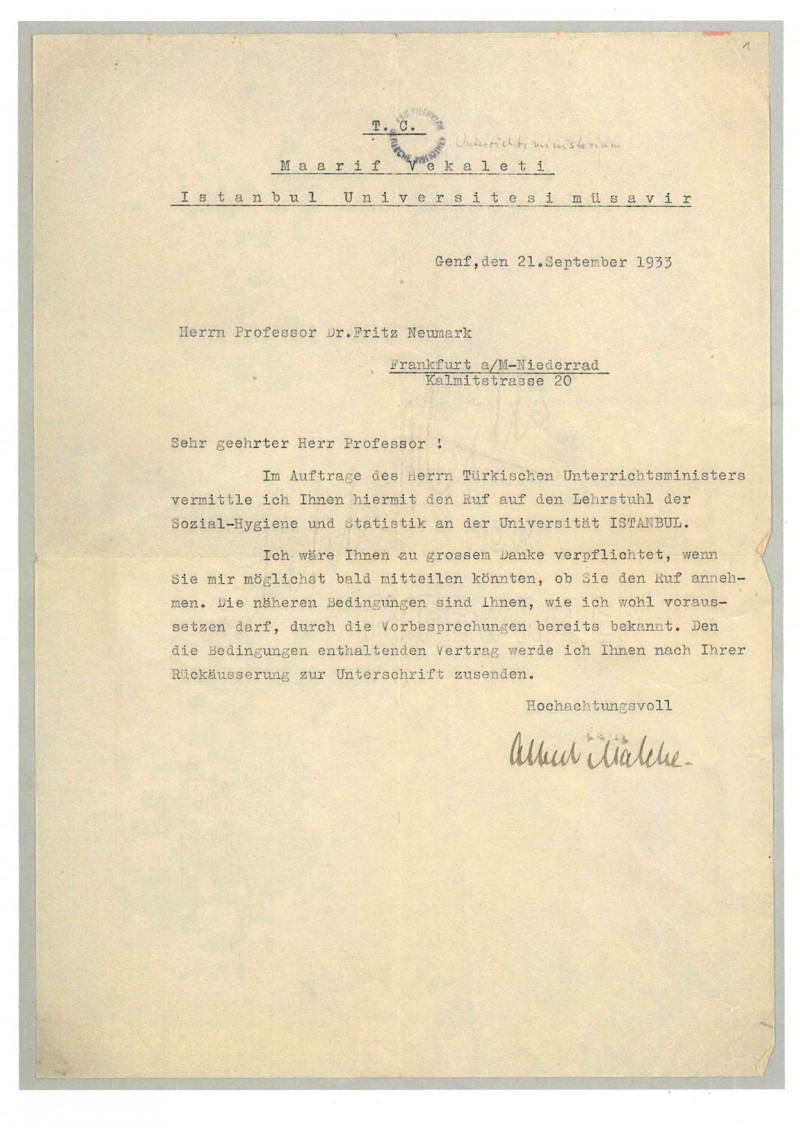

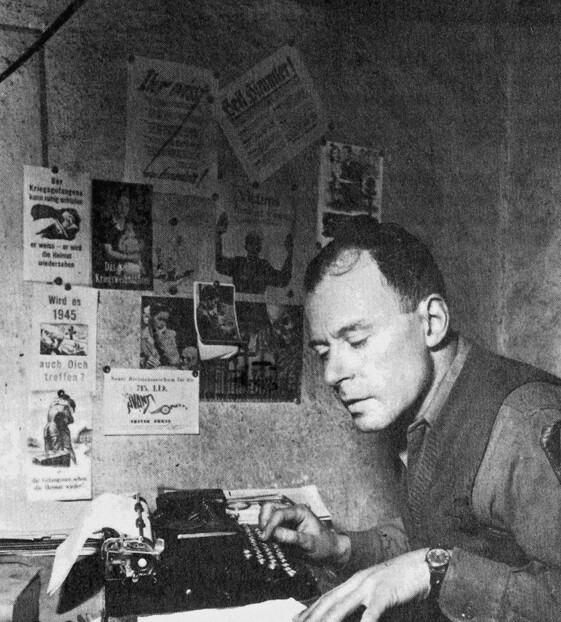

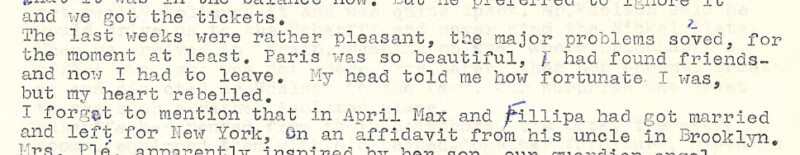

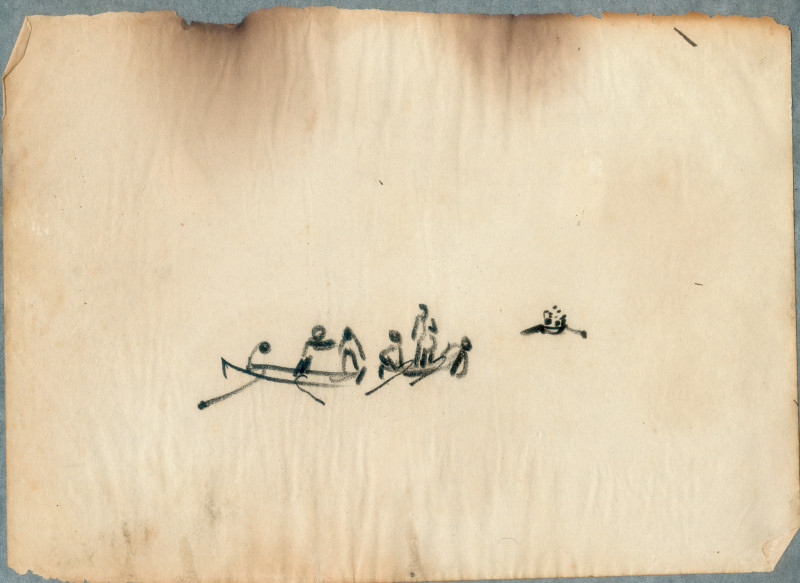

People do not only flee in order to escape any kind of danger to life and limb. At the same time, future is always inherent in flight, a look ahead, in which the hope of a safe arrival is combined with the individual will for a new beginning and concrete visions for the future. This momentum bears the potential of radical freedom through mobility, which is inscribed in this concept of the future itself. What lies before us does not necessarily arise from the past or is determined by it, but rather builds on the individual to proactively participate in shaping his or her own and collective not-yet.

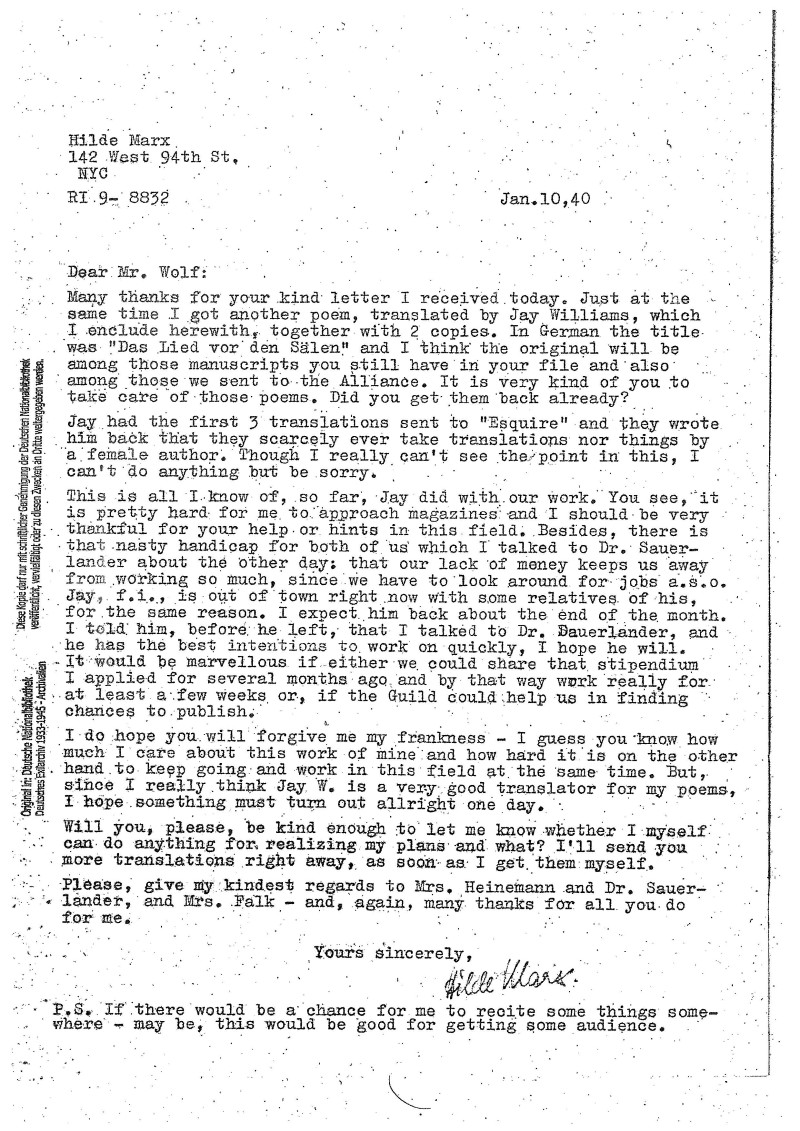

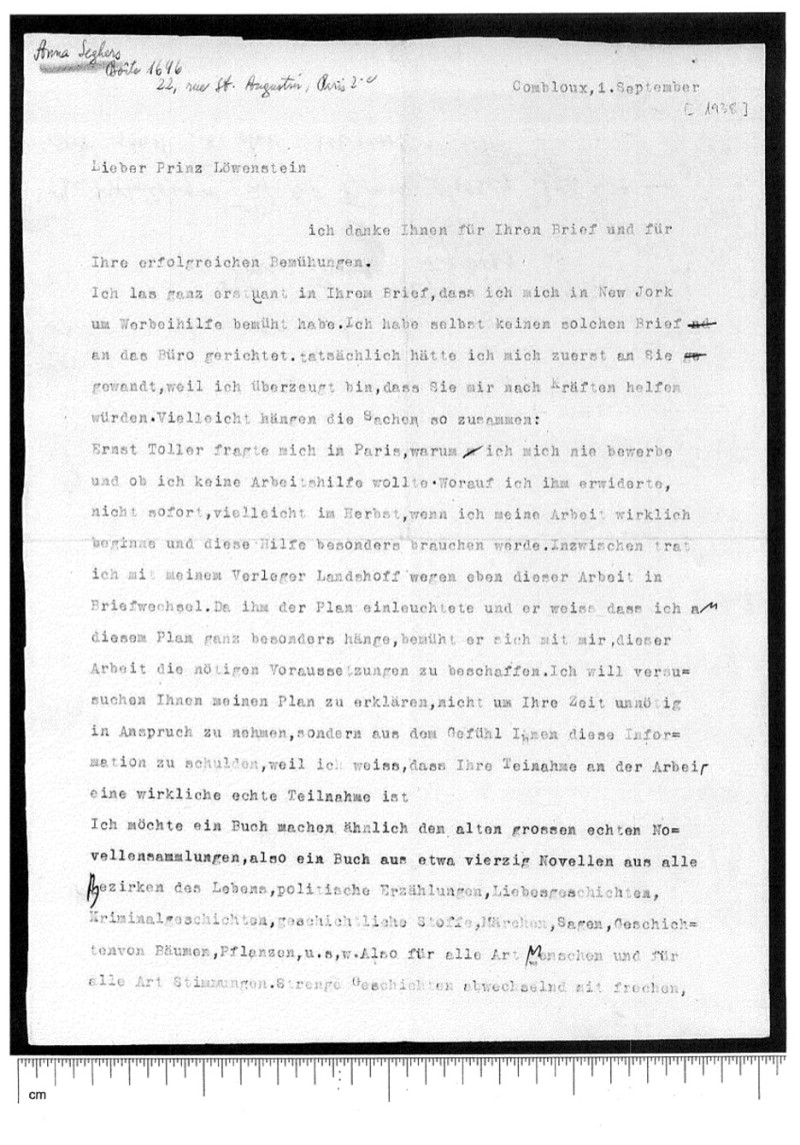

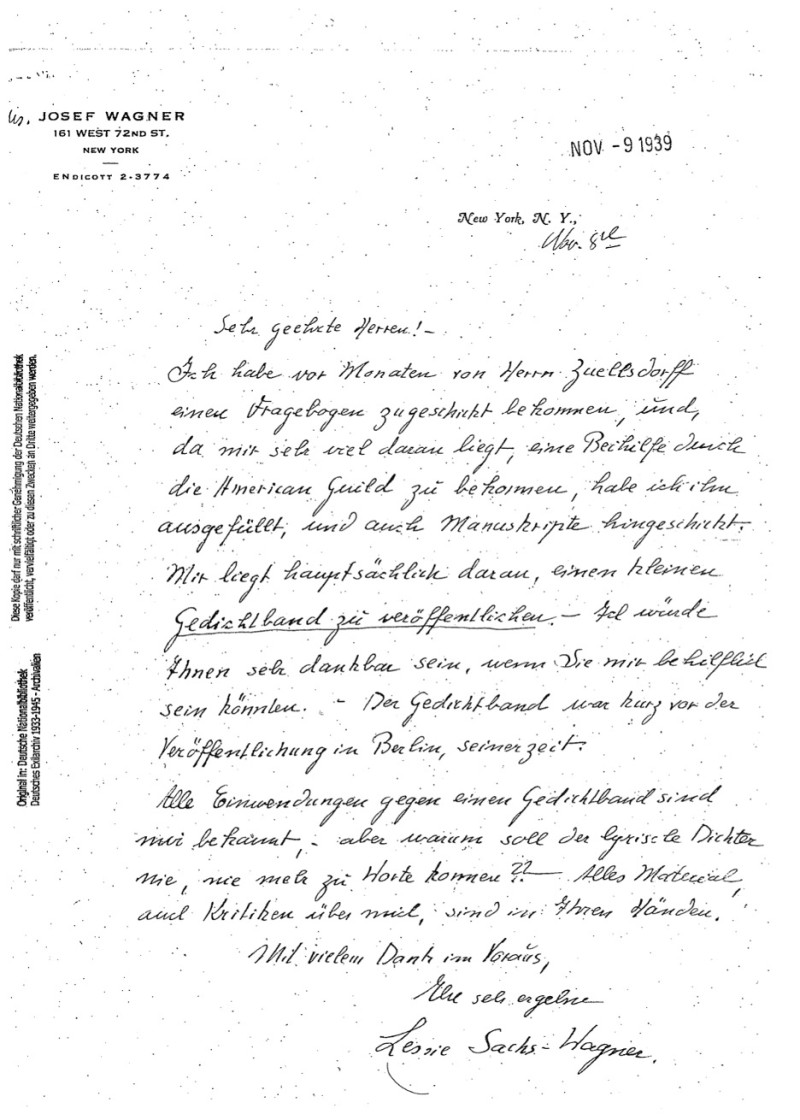

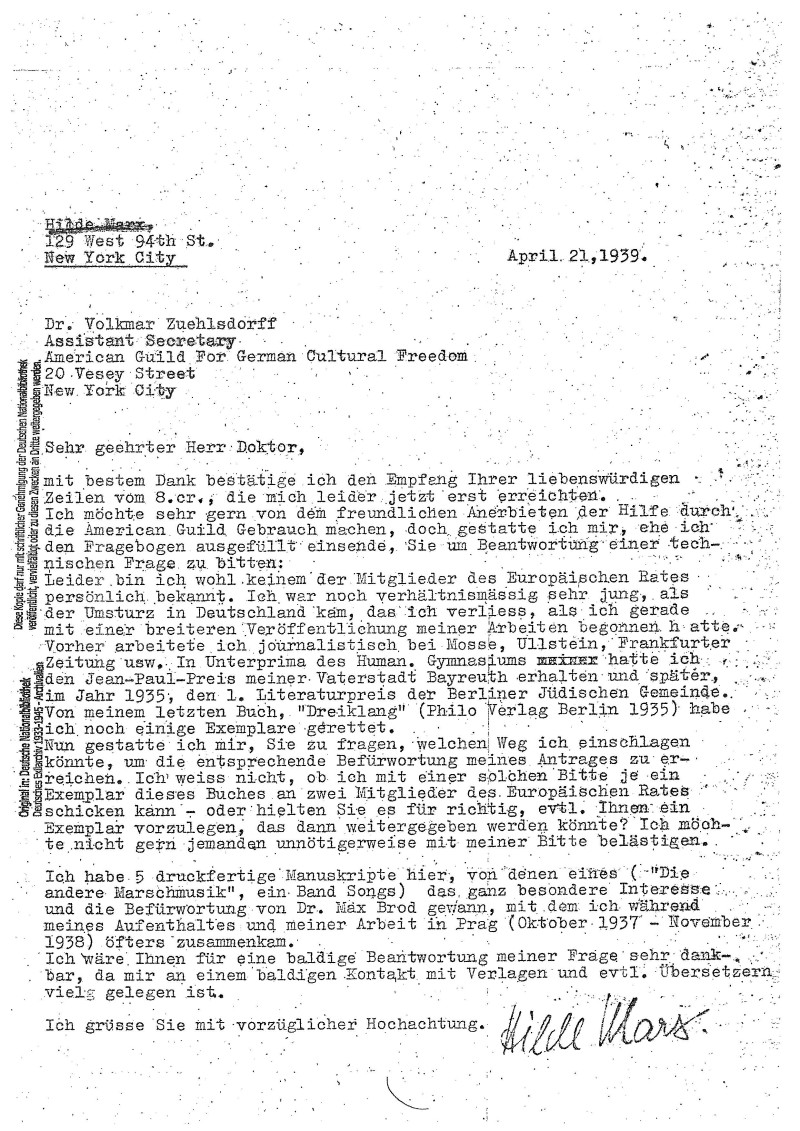

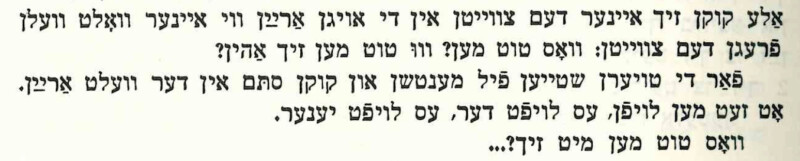

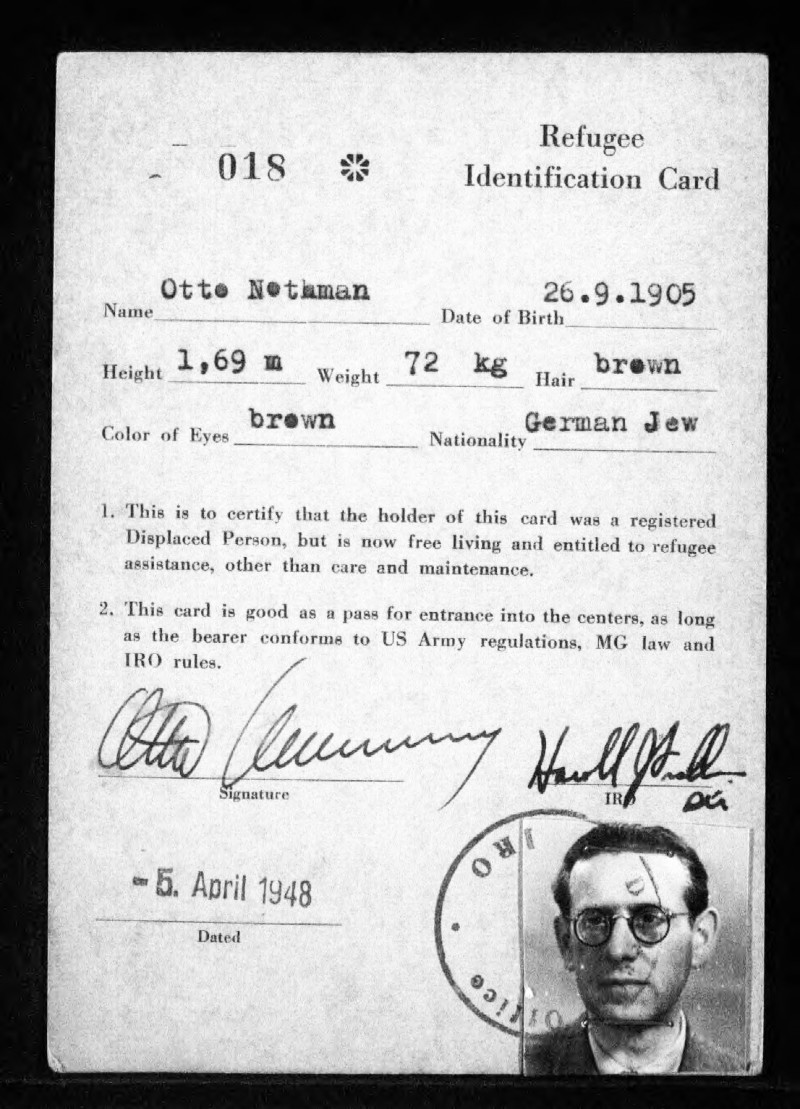

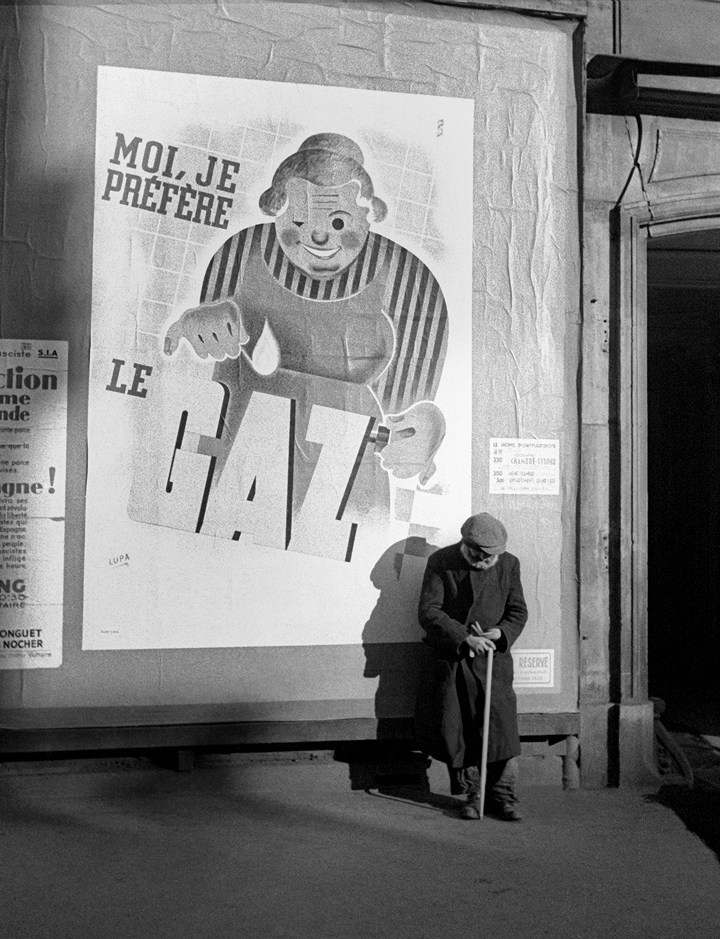

However, this migrant time continuum is often confronted with almost insurmountable obstacles of the present. Refugees often find themselves for years in a state of uncertainty, forced inactivity in overcrowded reception centers and suffer from legal discrimination, racism and the indoctrinated feeling of being obliged to act in a way that their new environment expects from them. If the hope for a new beginning is lost due to obstacles experienced or a lack of perspectives, this often has fatal psychological consequences for those affected. Thus, the possibilities for a new beginning and the building up of an existence often have extremely different and uncontrollable starting conditions, which depend on temporal, spatial, political and individual criteria. Social access through language, education, community and mutual cultural recognition remains essential. The striving for social recognition is always fatally intertwined with the danger of having to give up a self-determined life and self-image that is independent of unclear criteria of integration.

“We are (and always were) ready to pay any price in order to be accepted by society.”

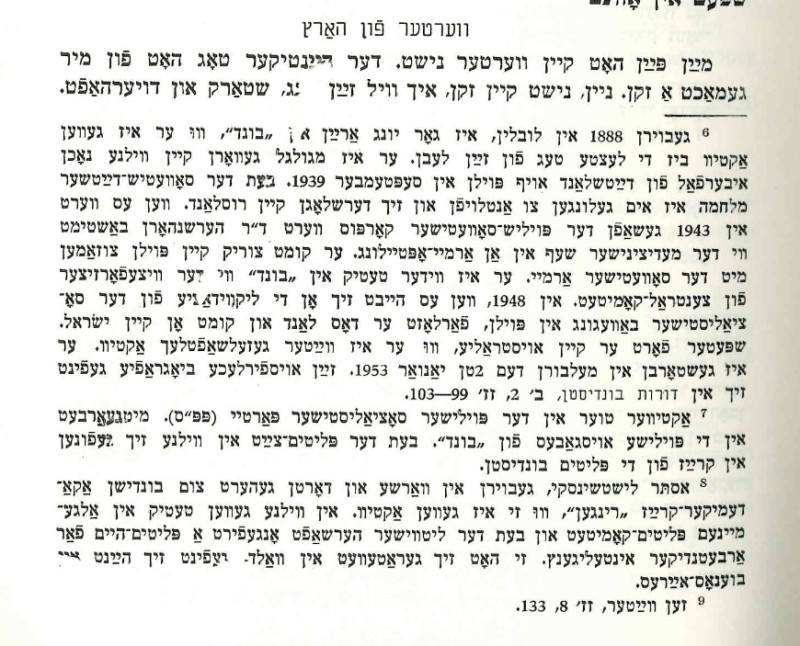

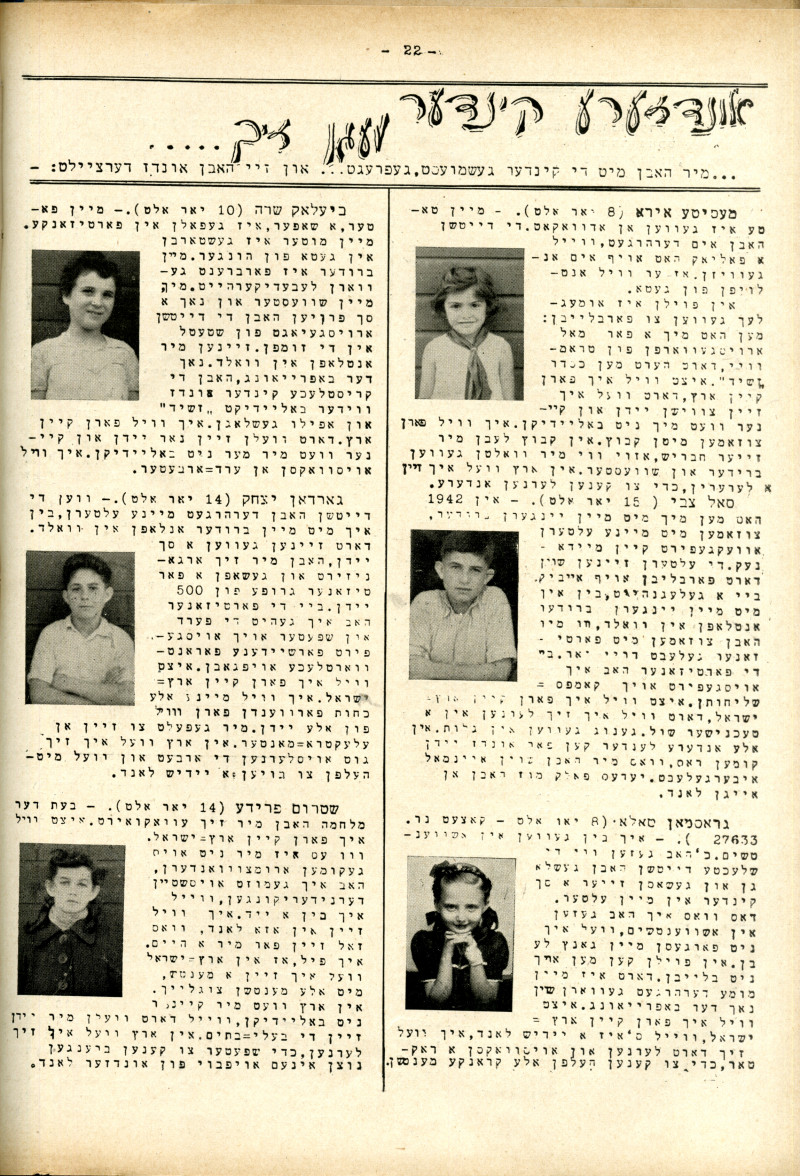

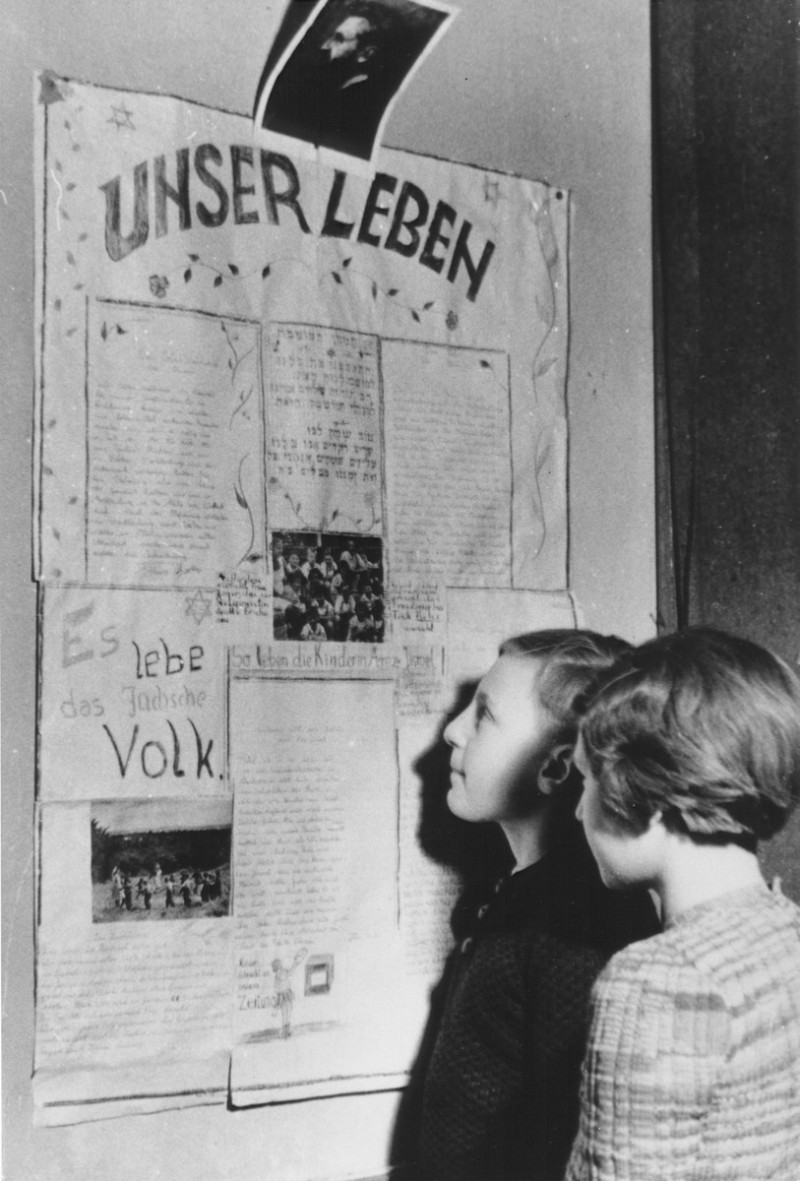

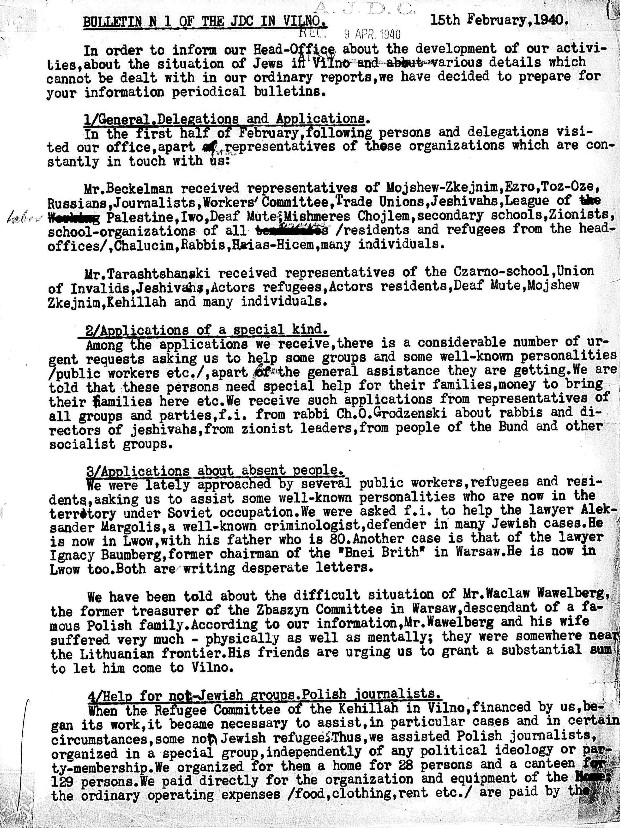

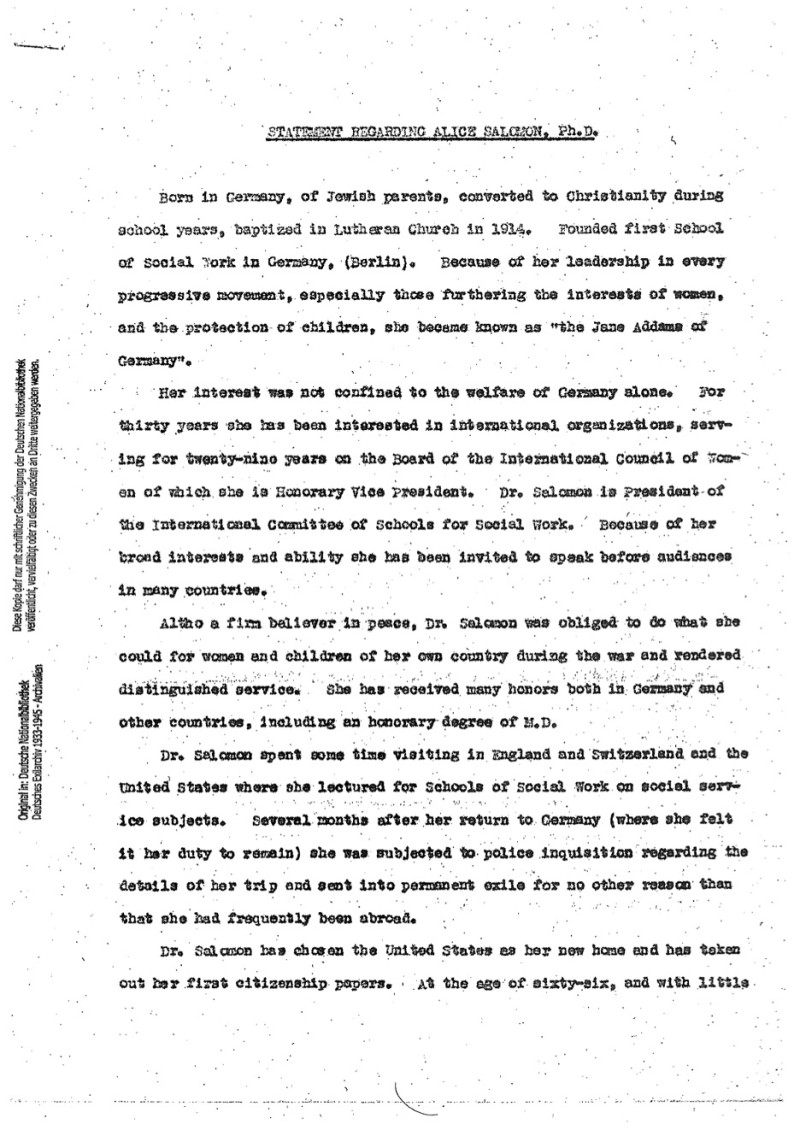

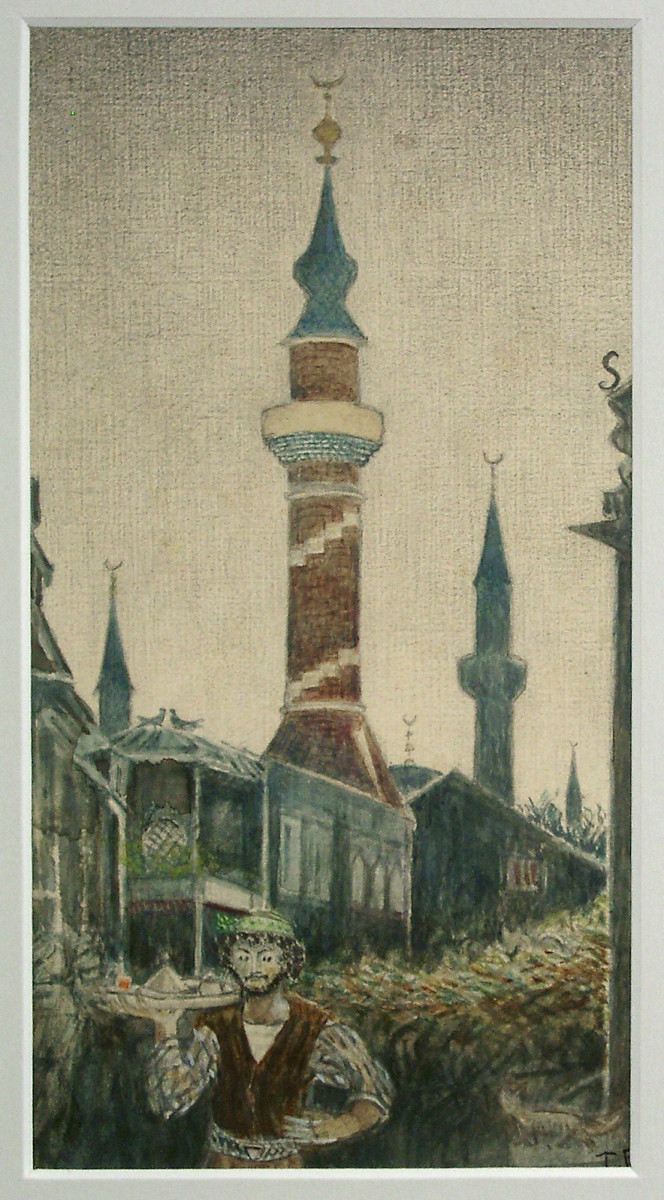

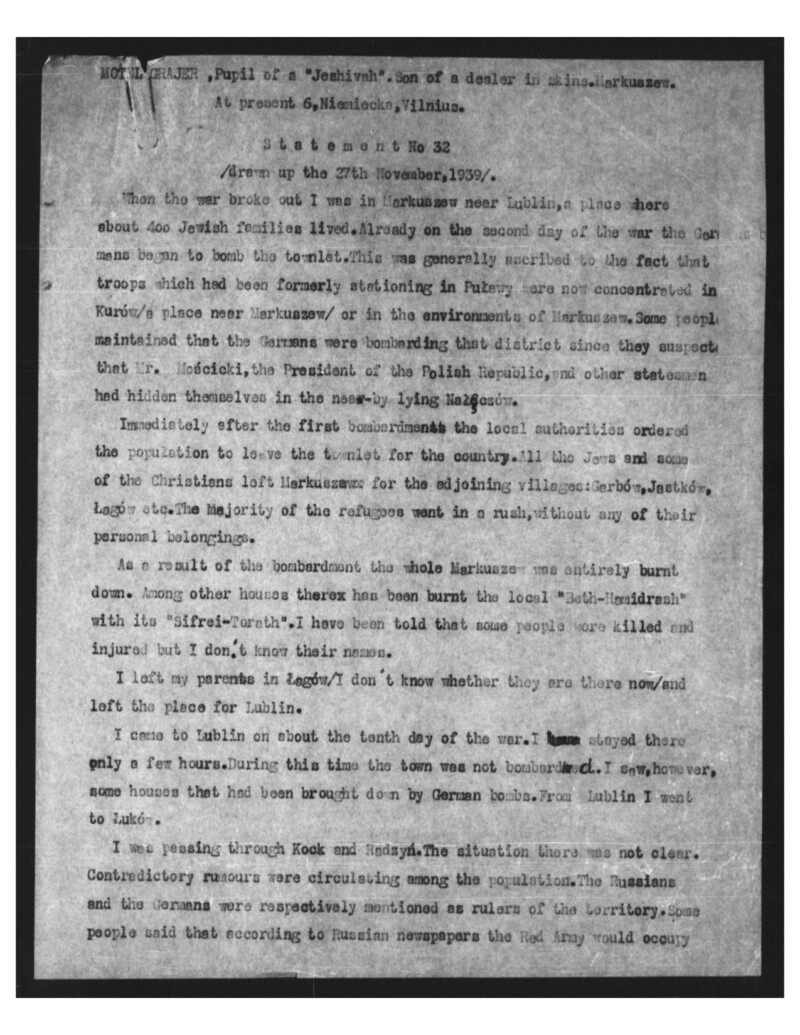

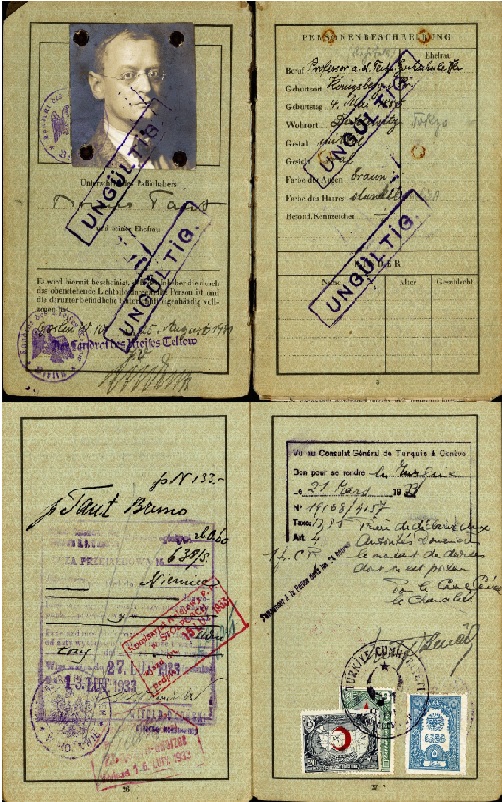

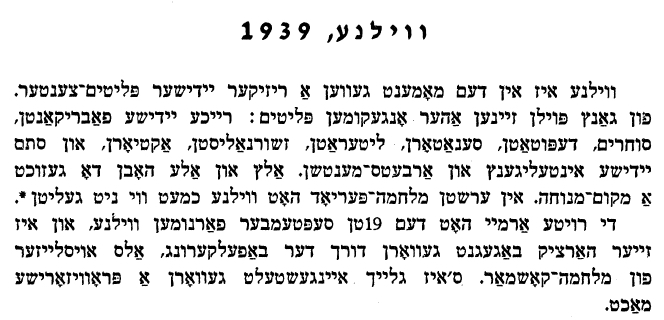

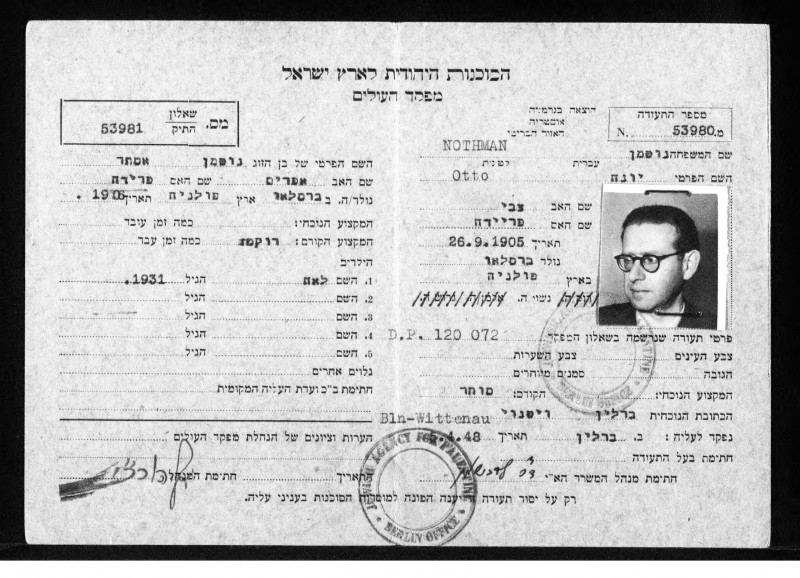

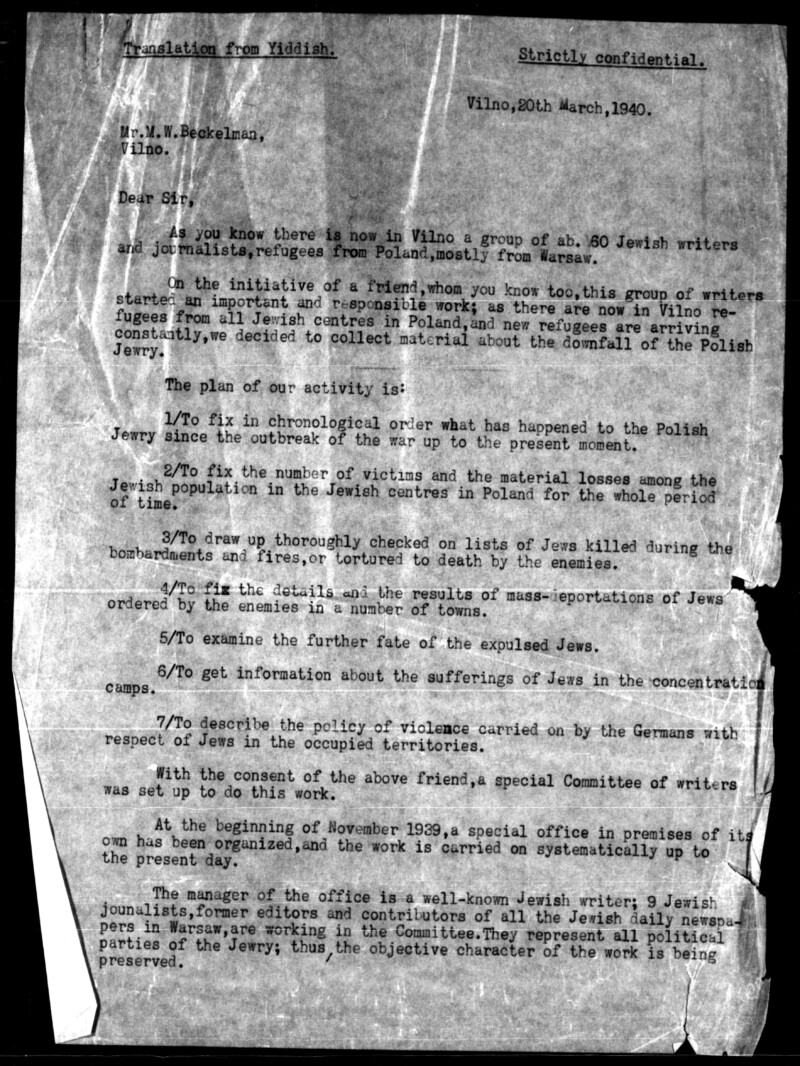

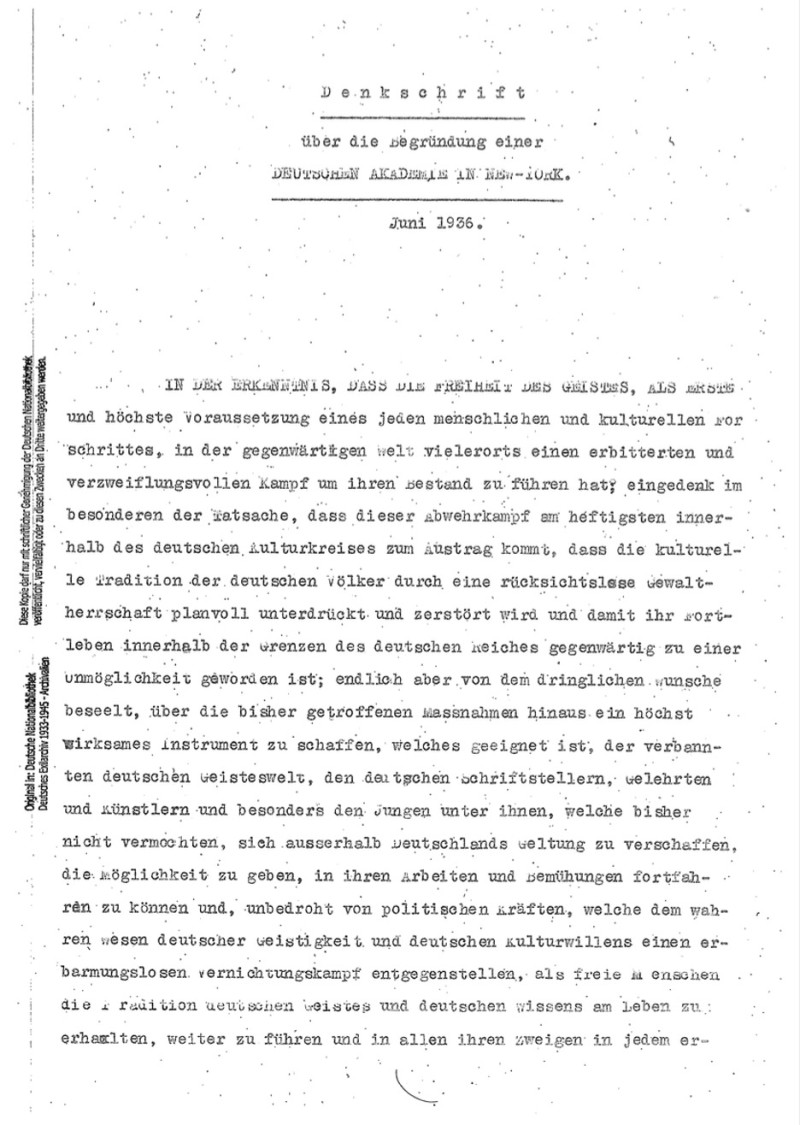

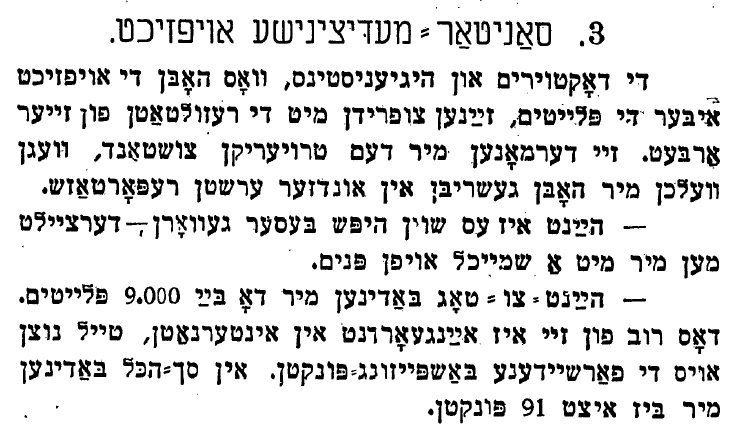

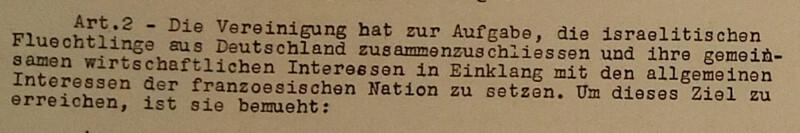

Thousands of Jewish refugees tried to survive in Vilnius in the early 1940s and to prepare for their onward journey or possible emigration to Palestine. Just like them, refugees in Europe today are often in a state of uncertainty for years. This raises the question of whether state immigration restrictions allow for a future stay in the host city with a view towards starting over. The behavior of the host society towards refugees here is crucial.

Thousands of Jewish refugees tried to survive in the Vilnius of the early 1940s, preparing for their onward journey or possible emigration to Palestine, America or other places promising security. Like them, refugees in Europe, such as in Palermo, are now often in a state of uncertainty and waiting for years. The question arises whether state immigration restrictions will allow them to remain in the city of refuge in the future with the prospect of a new beginning. Knowing that they could be forced to flee further or be deported every day, it is difficult to build a future in the place of refuge. Nevertheless, under the given conditions, they try everything possible to build the secure and fulfilling life they were heading for through education, networking and work.